Migration fuels human smuggling in the Mediterranean region

By Vasileios Koutsoliakos and Anastasios Filntisis

Over the past two years, the refugee crisis has risen to the forefront of European policy agendas. The increasing number of refugees and migrants who cross European Union borders daily has become a serious challenge — especially if we consider the profound changes it will cause to European societies. The migration has become a major facet of EU relations with the world. Taking into account that the management of migration is defined as a strategic priority with security concerns, member state governments need to establish coordination and cooperation models to address the phenomenon and counter organized crime networks that profit from it. The problem has two aspects that are connected and opposed to each other simultaneously: humanitarian crisis and security concerns.

Criminal organizations have adapted their activities to take advantage of refugee and migration flows. Human smuggling has become a lucrative industry. Therefore, EU governments and security authorities have to care for and accommodate refugees and at the same time handle security issues connected with the crisis. Arresting smugglers and defending against the possibility that terrorists may exploit migration routes to penetrate EU borders are the main security priorities. The EU approach to migration must be based on multilateralism and security governance.

Geopolitical context of the refugee wave

The current immigration influx and refugee wave — the biggest in Europe since the end of World War II — has produced an unprecedented level of security and humanitarian concerns. The phenomenon is directly related to changes taking place in the geopolitical and geostrategic environment of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region following the Arab Spring — the 2010-11 uprisings in several countries that failed to meet the people’s aspirations. On the contrary, they either brought chaos and destruction to state institutions, such as Libya becoming a failed state, or resulted in the restoration of the previous regime, as in Egypt.

In Syria, the first demonstrations in January 2011 were influenced by similar rebellions in nearby countries. The protesters asked for the restoration of their civil rights and an end to an emergency law in place since 1963. The uprising against President Bashar Assad’s regime escalated in March 2011 with the biggest demonstrations in decades taking place in the capital, Damascus. Assad’s unwillingness to abdicate his authority — and reduce the influence of the Alawite sect to which he belonged — plunged the country into a bloody civil war that led to a massive exodus of the population, the majority of which found safe haven in the neighboring countries of Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. They had hoped for a quick end to the conflict and to return home.

The continuance of the Syrian civil war, the withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Iraq and the resignation of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki all led to the instability of the Iraqi government and expansion of jihadists in Iraq. Despite expectations, the Syrian conflict has converted into a proxy war, in which international and regional players are involved, attempting to affect the outcome based on various geopolitical, political, economic and religious interests. A difficult situation was made worse by the emergence of ISIS. Its elevation into the Islamic State by its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had the effect of provoking airstrikes from the U.S. and its allies. ISIS instituted a policy of extreme violence and brutal suppression of religious minorities, resulting in an increasing number of refugees and immigrants seeking safety. The current situation leaves little hope for a quick end to the civil war. Additionally, Russian armed forces involvement in Syria in support of the Assad regime, with airstrikes against terrorist organizations and anti-regime groups, have further complicated the choices of international players.

Until the Syrian war is resolved, more and more Syrians can be expected to give up the prospect of returning home and try to build a new life in Europe. The control and subjection of large parts of Iraq and Syria by the Islamic State complicates potential solutions despite efforts in Geneva to reach agreement on a gradual de-escalation. Furthermore, in Afghanistan, the withdrawal of most NATO forces and the government’s failure to take control of the state have led to a perpetual state of instability, with the Taliban attempting to restore control over the region. Therefore, unsurprisingly, Afghans, Iraqis and Syrians are the three main constituents of the refugee and migrant wave. The magnitude of the refugee crisis and immigration issue has created serious friction among EU member states.

Smuggling networks and organized crime

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and its communist satellites in Eastern Europe, organized crime flourished, according to Misha Glenny, who wrote in The New York Times in September 2015 about the connection between organized crime and the refugee crisis. Organized crime networks and groups took advantage of globalization and relaxed law enforcement in the Balkan Peninsula to control drugs, weapons and human trafficking. Similarly, the failure of uprisings in Arab countries — the fiasco of the Arab Spring and the persistent instability in Syria, Iraq and Libya — has provided fertile ground for illegality. Organized crime networks and facilitators exploited the crisis in the Middle East and Africa and turned their operational capabilities to smuggling, which has been highly lucrative. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the refugee crisis is seen as a great opportunity by organized crime groups to profit from smuggling; human smuggling and trafficking have become one of their most lucrative activities, second only to the drug trade.

These groups have helped transport thousands of economic migrants from underdeveloped countries who desired to enter EU territory illegally. The breakout of insurrections in the MENA region in 2010-11 gave smugglers the opportunity to exploit those trying to avoid conflict zones. Since then, there has been a substantial change in the number of entrants and in their status as refugees or immigrants. At the same time, smugglers continue their illegal migration activities, moving people from the MENA region and other undeveloped countries who try to enter Europe as refugees, maximizing the flows.

The “big march” has pressured EU Mediterranean countries and central and northern EU member states that are destination countries for most of the immigrants and refugees. In previous years, major smuggling routes were from Libya to Italy and from Turkey to Greece, in connection with the conflicts in Libya and Syria.

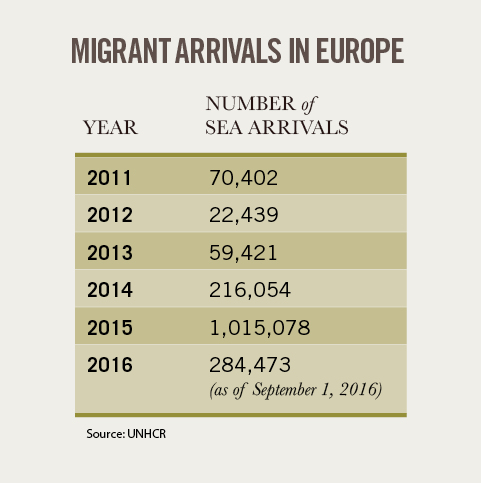

The year 2015 was a watershed for two reasons: Greece and the Balkans corridor became the main route for refugees, and there was a substantial increase in the number of refugees who tried to enter the EU, a figure officially estimated at 1 million. These numbers have risen for a number of reasons: First, the EU sought to ease pressure from the Libyan coast with the establishment of Operation Sophia; second, since 2011 Syria remains the primary battlefield in the Mediterranean basin and, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), about 4.5 million Syrians have become refugees from the civil war, not counting internally displaced people; and third, Germany, which is the main destination for refugees, adopted a policy of open borders (Willkommenpolitik) in 2015 against the wishes of most citizens.

International and European cooperation

The U.N. response to organized crime’s smuggling was the Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. Its provisions set the general framework to deal with the phenomenon, but the current European case needs more specific and urgent measures. There is a common belief and realization at the EU level that no member state can combat transnational organized crime — let alone smuggling or terrorist-related activities — without coordination and cooperation at a strategic and operational level.

The president of the European Commission mentioned the need for security coordination in his Political Guidelines in July 2014, and the EU Commission adopted in April 2015 the European Agenda on Security for 2015-2020, in which two of the three main priorities focus on combating terrorism and organized crime. In May 2015, EU ministers decided to take action against the smugglers who operate from the coasts of Libya with the establishment of the European Union Naval Force-Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED), a military operation under the Common Security and Defense Policy framework. The mission of EUNAVFOR MED is being developed in three phases: 1) gathering and sharing intelligence on irregular migration networks and tracking vessels used or suspected of being used by traffickers; 2) boarding, search, seizure and diversion on the high seas of suspected vessels, as well as in the territorial and internal waters of the coastal state if there is a U.N. Security Council resolution and/or the consent of the state; and 3) EUNAVFOR MED forces would be allowed to take all necessary measures against suspected vessels, including disposing of them or rendering them inoperable, if there is a security council resolution and/or the consent of the state. In October 2015, the U.N. supported the EU operation (renamed “Sophia” and later changed to “Phase 2”) with Security Council Resolution 2240/2015, which “authorized its members to act nationally or through regional organizations for the seizure of vessels that are confirmed as being used for migrant smuggling or human trafficking from Libya.” On June 20, 2016, the Council extended the operation’s mandate — until July 27, 2017 — because of increased flows from Libya since the implementation of the EU-Turkey agreement and the closing of the Balkan route. At the same time, the operation was reinforced with two supporting tasks: training the Libyan coastguard and navy to support the operation and contribute to the UN arms embargo on the high seas off the coast of Libya because of the civil war in the country.

The EU Commission’s proposed “Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard” can contribute to more integrated border management. According to the proposal, border management “will be based on the four-tier access model, which comprises measures in third countries, such as under the common visa policy, measures with neighboring third countries, border control measures at the external border itself as well as risk analysis, and measures within the area of free movement, including return.”

Taking mixed migratory flows into account, a revision of the EU return system can help confront smuggling networks, which exploit the fact that relatively few return decisions are enforced and, as a result, irregular migrants have a clear incentive to use illegal migration routes to enter the EU. A more realistic and assertive policy in that field can have a major impact on illegal migration flows and will raise the stakes for those willing to enter the EU illegally, simultaneously causing economic damage to smugglers and facilitators. According to the European Agenda on Migration provisions, the EU has set a goal of resettling 20,000 migrants per year by the year 2020. The policy is a move in the right direction because the resettlement of people from third countries reduces the role of smugglers and secures a safe entry method for refugees in the EU.

At the same time, the proposals for improved intelligence sharing and financial support coordination in third countries, in which a large number of refugees have already been concentrated in camps, can contribute to containing refugee/migrant flows. Although the EU proposals have been a step in the right direction, adoption and implementation delays have caused friction among EU member states. As a consequence, several member states are attempting to confront the refugee crisis at a national or regional level with stricter measures, including the construction of border fences. It is doubtful whether such efforts will bear fruit because they do not offer a solution to the smuggling problem. Smugglers are resilient; they change their routes and then raise fees to account for the increased difficulty of the “new” route. A more constructive approach would promote a more ambitious resettlement plan via cooperation with third countries and the establishment of “hot spots” in their territory to accept, check and host, at least temporarily, victims of war.

Despite these measures to control and confront the phenomenon, EU member states need more coordinated efforts to alleviate pressure from these unprecedented migrant flows. With more than a million migrants having reached Europe in 2015, and a 16-fold increase in the number of refugees/immigrants arriving on EU territory in the first 40 days of 2016 (compared to the same period in 2015), NATO began to take a role in the crisis.

NATO defense ministers decided to introduce a naval operation in the Aegean Sea in February 2016. The proposal for NATO intervention was raised for the first time only two days before the NATO meeting, after talks between German chancellor Angela Merkel — whose country is the main destination for migrants — and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was confronting a new wave of refugees from Syria because of the siege of Aleppo by Assad’s forces. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg stated that “the goal is to participate in the international efforts to stem the illegal trafficking and illegal migration in the Aegean.”

Additionally, NATO will establish a direct link with the EU’s border management agency, Frontex. The swiftness of the decision reflects the urgency of the situation; details about the tasks and the level of engagement of the mission are yet to be determined. However, as the secretary-general of NATO stressed, this mission is “not about stopping or pushing back refugee boats,” but about contributing “critical information and surveillance to help counter human trafficking and criminal networks.” Taking all this into account, a crucial question emerges: Would NATO’s operational involvement have a practical effect on limitating and improving control of refugee flows? Despite doubts about the efficacy of the operation, the agreement comes with several advantages, such as:

1. It reflects a clear commitment to counter organized smuggling networks. As U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter said: “There is now a criminal syndicate that is exploiting these poor people, and this is an organized smuggling operation.”

2. NATO involvement is expected to improve information and surveillance cooperation, thanks to its operational and technical capabilities.

3. NATO has a proven track record of search-and-rescue and antipiracy efforts.

4. NATO’s prestige may have a positive effect on the fight against smuggling.

5. NATO patrols, unlike the EU’s maritime mission off the Italian coast, will return migrants to Turkey — a fact that may lead to a decrease in the flows.

6. NATO ships will operate on both sides of the maritime boundary separating Greece and Turkey, unlike the two countries’ own coastal vessels that only operate in their respective waters.

Although it seems too early to make positive or negative conclusions on whether NATO’s involvement will deter human trafficking, this operation could be a game changer. Furthermore, whether NATO will enhance its surveillance of Turkish-Syrian borders, monitor the movement of refugees/migrants and especially the activities of smugglers, is still being discussed.

The European Commission welcomed the plan but said it will create an effective EU border and coast guard system to fulfill the same operational function.

During the last few months, NATO operations, the closing of the Balkan corridor and especially the EU-Turkey agreement had the effect of controlling quite effectively irregular migration flows. Since March 20, there is a staggering decrease in the number of refugee who entered EU territory. Despite the positive outcome, there are serious concerns that the agreement will not last long because of frictions between the EU and Turkey about specific aspects of the agreement.

Potential terrorism implications

Apart from the humanitarian and social dimensions of the refugee crisis, security remains an important concern. As mentioned, organized crime groups are profiting from the refugee/immigration problem. Articles like Anton Troianovski’s and Marcus Walker’s “Paris Terror Attacks Transform Debate Over Europe’s Migration Crisis” in The Wall Street Journal have raised questions about the connection between the migrant/refugee problem and terrorist-related activities. Before the Paris terrorist attacks in November 2015, security officials were hesitant to speak about any interaction or connection between the refugee wave and terrorism. The fact that two of the perpetrators had been registered in Greece and other European countries before their arrival in Paris to execute their mission brought to light the possibility that al-Qaida, ISIS and other affiliated groups could exploit refugee flows to penetrate EU borders and conduct attacks. At the same time, the propaganda campaigns of terrorist groups, along with direct threats against European countries by jihadists via the internet, have raised security awareness and instilled fear in our societies.

The aforementioned discussion among EU member states puts into question the Schengen open border policy and has led European countries to adopt stricter policies nationally or regionally. After the Paris attacks, leaders from several countries withdrew from the obligation to receive refugees from Greece and Italy as part of the relocation program, as their governments yielded to pressure from populist and far-right parties to follow intransigent policies by closing borders. It is understandable that the matter raises concerns, not only for security reasons but for the social impacts. Conversely, it is also true that the probability of terrorists posing as refugees is exaggerated. Taking into account that only a handful of people, from almost 1 million refugees and migrants who entered the EU the previous year, are connected to terrorist attack, the percentage is statistically negligible. Europol, in a January 2016 report, Changes in Modus Operandi of Islamic State Terrorist Attacks, states: “There is no concrete evidence that terrorist travelers systematically use the flow of refugees to enter Europe unnoticed.” On the contrary, Europol and security experts from EU member states focus on the return of foreign fighters — mainly religiously motivated individuals who left their countries of citizenship to train or fight in combat zones. These people, mainly unpaid, pose a potential threat to Western countries on return because they have increased capability and intent. Returnees can act as Islamic extremist recruiters and target Syrian refugees who enter Europe.

The European Agenda on Security makes no reference to a connection between the refugee crisis and terrorism. On the contrary, in the “Tackling terrorism” section, the focus is on foreign fighters. The attack at the Brussels Jewish Museum in May 2014 is considered to be the first completed terrorist attack by a Syrian returnee in Europe (not to mention a number of similar plots that have been disrupted by EU law enforcement agencies). The example underlines the threat posed by Syrian fighters returning home to EU countries.

What must be done?

Dealing with the rising wave of refugees/migrants is undoubtedly becoming one of the most serious security challenges for European societies. The EU needs to act concretely to confront the problem without hurting the common European establishment.

First, Greece and Italy should implement all the necessary measures for registering and mapping refugees and migrants who enter EU territory. The two countries, and especially Greece, which carries the main burden, have to establish “hot spots” at entrance points to register, check and interview individuals.

Second, the remaining member states should implement the agreement for the relocation of 160,000 refugees from Greece and Italy without delay, as this will be the first coordinated step to tackle the refuge crisis. At the same time, the EU needs to establish an innovative and comprehensive system to achieve a more efficient return program and manage people who are not characterized as refugees, i.e., economic migrants. According to June 2016 statistics, there was a substantial decrease in the daily number of refugees entering EU territory through Greece’s sea borders. In particular, after the EU-Turkey agreement in March 2016, the total number of inflows was about 8,500 (March-June 2016), in contrast to the previous year when 1,000-1,500 migrants entered Greece every day during the same period.

Third, the NATO operation and the rapid establishment of a new European Border and Coast Guard agency can deliver a decisive blow to smuggling networks that exploit the refugee crisis. One vital prerequisite for the success of this mission is Turkey’s cooperation as a third partner of consensus. In this framework, Europol announced in February 2016 that the function of the European Migrant and Smuggling Center will be to support EU member states in dismantling criminal networks involved in organized migrant smuggling.

In addition to the aforementioned initiatives and measures, the EU must build effective partnerships with third-party countries in the MENA region, Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia for more efficient management of refugee/migration flows through bilateral or multilateral agreements with countries of origin or transit.

Finally, the EU needs to intensify diplomatic efforts globally to create a permanent cease-fire in Syria and a political solution, together with a mission to confront ISIS and other terror groups.

Regarding terrorism, official reports state that there is no concrete evidence linking terrorism to refugee/migrant flows. Although we cannot exclude such a potential threat, the foremost danger comes from homegrown terrorists. According to Europol’s latest EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, the radicalization phenomenon is growing. The threat posed by homegrown terrorists, radicalized lone attackers, “frustrated” terrorist travelers and foreign fighters is genuine and should not be underestimated, with the understanding that numerous attacks have been disrupted by security services in the EU and other Western countries (e.g., the U.S., Canada and Australia) over the past 12 months.

Another concern is potential radicalization of newly arriving refugees/immigrants in detention areas. Personal disillusionment and religious vulnerability during the “big march” can create a fertile ground for violent extremism. The EU should coordinate its policies for the integration of refugees into European communities and oppose exclusion and the creation of parallel communities. First contact is important, and a total effort to tackle social isolation is a key factor in countering this type of radicalization.

Comments are closed.