Refugee situations require international solutions

By Katharina Lumpp, representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Germany

Photos by UNHCR

The thousands of refugees seeking protection in Europe during 2015 and 2016 brought renewed attention to their plight. Men, women and children on the move and in need of protection and assistance — familiar sights in Africa, Southwest Asia and the Middle East — were now arriving at Europe’s borders.

Though large movements of refugees are often associated with other parts of the world, the phenomenon is part of Europe’s history. Europe is where the global international system to protect refugees was first conceived and where the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was drafted in the wake of World War II. The convention is the foundation of the international refugee protection system and was born of a necessity to provide a principled response to refugee movements. Its drafters drew on principles embedded in cultural and religious traditions and enshrined them in international law.

One of the founding principles of the 1951 Convention is that refugees are an international, shared responsibility. Its preamble notes “that the grant of asylum may place unduly heavy burdens on certain countries, and that a satisfactory solution of a problem of which the United Nations has recognized the international scope and nature cannot therefore be achieved without international cooperation.”

The need for international protection arises when people are outside their country and unable to return home without risking their safety. Risks that give rise to a need for international protection include persecution, threats to life, freedom or physical integrity arising from armed conflict, serious public disorder or other threats of violence. With record numbers of people uprooted and displaced as a result of such risks, the challenge lies in achieving the necessary international cooperation to equitably share the responsibility for protecting refugees.

Global Trends

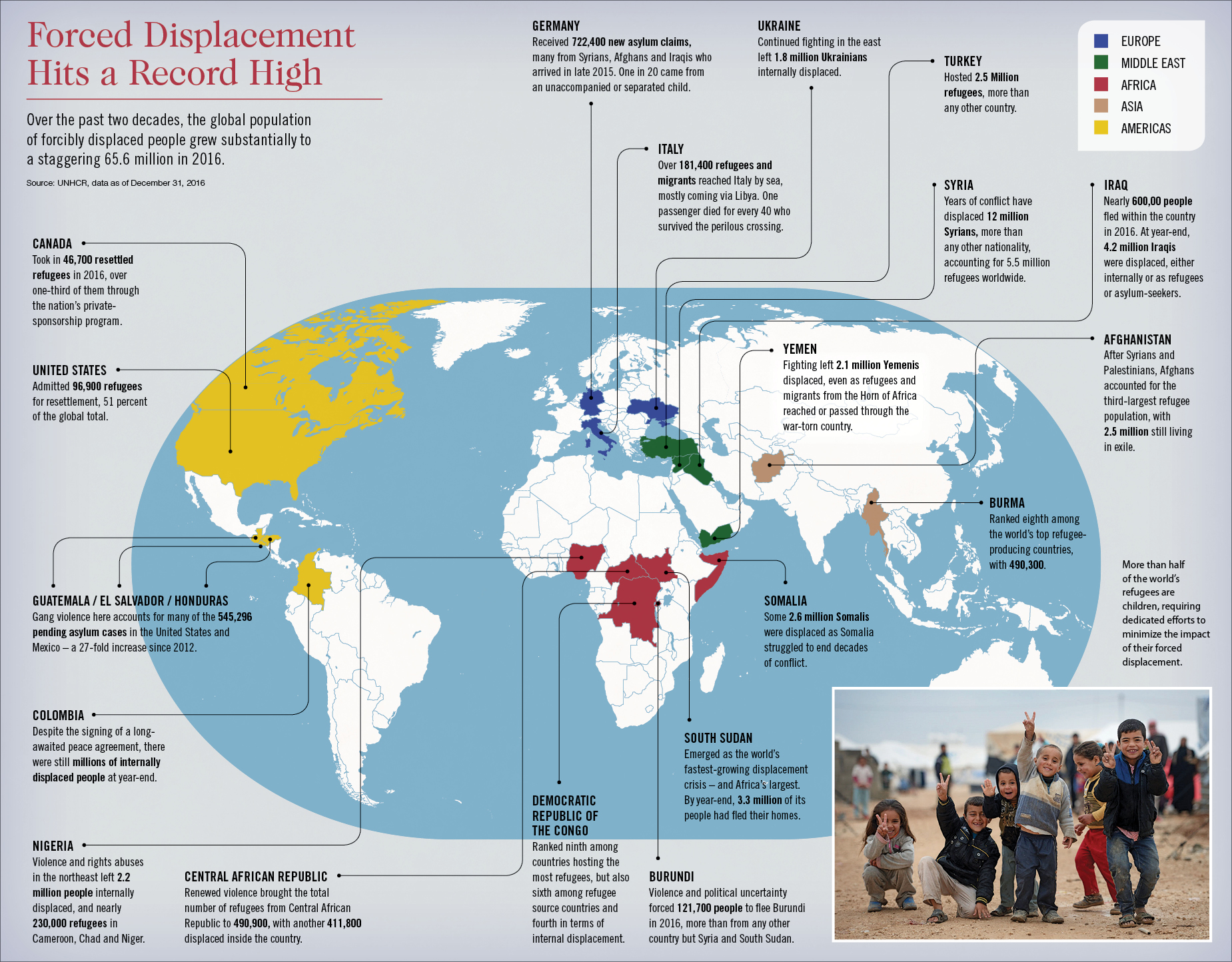

Every year on June 20, World Refugee Day, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) publishes its report on the global trends of forced displacement. Over the past two decades, the global population of forcibly displaced people has grown substantially — to a staggering 65.6 million people in 2016 — and remains at a record high. During that year, 10.3 million people were newly displaced, equivalent to an average of 20 people displaced every minute of every day.

The majority did not cross international borders: Of the 65.6 million people forcibly displaced worldwide, an estimated 40.3 million were internally displaced within their own countries. Some 22.5 million people were refugees, including 17.2 million refugees under a UNHCR mandate, and 5.3 million Palestinian refugees registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. The global displacement figure also includes 2.8 million asylum-seekers waiting for a decision on their fate.

Globally, 51 percent of the world’s refugees are children, requiring dedicated and focused efforts to minimize the impact of forced displacement on them. The number of particularly vulnerable unaccompanied or separated children was also significant: an estimated 75,000 unaccompanied or separated children, mainly Afghans and Syrians, applied for asylum in 70 countries, a figure assumed to be an underestimate.

Globally, 51 percent of the world’s refugees are children, requiring dedicated and focused efforts to minimize the impact of forced displacement on them. The number of particularly vulnerable unaccompanied or separated children was also significant: an estimated 75,000 unaccompanied or separated children, mainly Afghans and Syrians, applied for asylum in 70 countries, a figure assumed to be an underestimate.

While attention largely focused on the movement of refugees and migrants across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe, a majority of today’s refugees, an estimated 84 percent (about 14.5 million people) remain in developing regions. This includes Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan and Uganda, all of which are providing asylum to a growing proportion (28 percent) of global refugees.

By the end of 2016 some 60 percent of refugees were living in urban areas and not in refugee camps or settlements, according to the UNHCR. This highlights the increasingly urban nature of the refugee population and the growing need to support those communities and countries hosting refugees. In particular, the Syrian refugee situation was characterized by a very large urban refugee population: 90 percent of Syrian refugees lived in private or individual accommodations, as opposed to camps.

Refugee Situations

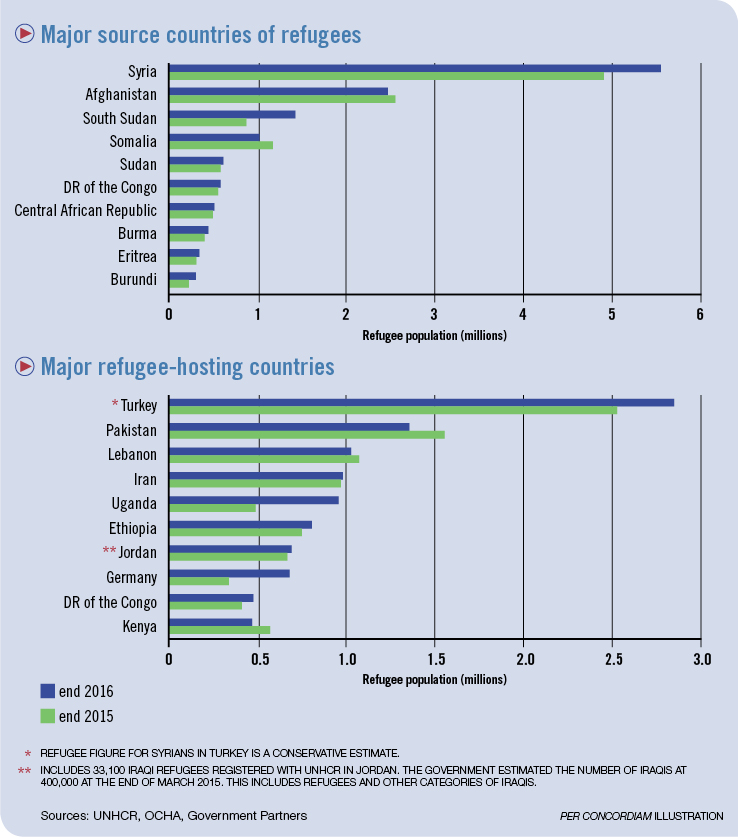

The main countries of origin of refugees, accounting for 79 percent of the global refugee population under UNHCR’s mandate, are Afghanistan, Burma, Burundi, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Syria.

With more than half its population displaced internally or across international borders, Syria remained the main country of origin of refugees in 2016, with 5.5 million at the end of the year. While Syrian refugees were hosted by 123 countries on six continents, 87 percent remained in the countries neighboring Syria. Turkey hosted the most (2.5 million), while Lebanon (1 million), Jordan (648,800), Iraq (230,800) and Egypt (116,000) also hosted significant numbers.

Beyond the region, countries with large Syrian refugee populations included Germany (375,100) and Sweden (96,900). With prospects remaining elusive for a peaceful settlement of the conflict, it is important to focus on supporting these refugees and the countries hosting them.

Refugees from Afghanistan comprised the second largest group by country of origin. At the end of 2016, there were 2.5 million Afghan refugees. Pakistan hosted the largest number (1.4 million), with Iran not far behind with 951,100. Afghanistan also experienced record levels of conflict-induced internal displacement during 2016. An estimated 623,200 Afghans were newly displaced that year, exceeding the number of newly displaced in 2015 and adding to an existing caseload of protracted displaced people estimated to total more than 1.2 million. Afghans were displaced from 31 of the country’s 34 provinces.

But the fastest-growing displacement crisis is occurring in South Sudan. Armed conflict combined with economic stagnation, disease and food insecurity have plunged the world’s youngest country into desperation. By the end of 2016, about 3.3 million South Sudanese had been forced from their homes. In total, about 12.9 million remain internally displaced and 1.4 million have fled to neighboring countries, with Uganda the top destination. One out of every four South Sudanese has been forcibly displaced.

In Uganda, the refugee population increased more than threefold to 639,000 during 2016 and continues to grow. Over a 12-month period beginning in the middle of 2016, an average of 1,800 South Sudanese arrived in Uganda every day. By August 2017, the total had reached 1 million. In addition, 1 million or more South Sudanese refugees are being hosted by Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya and Sudan.

Two-thirds of the refugees from South Sudan are children under the age of 18. Women make up 63 percent of the adult refugees. The crisis is overwhelmingly rural in nature, with 91 percent of the refugees forced to move from rural communities in South Sudan to rural locations in their countries of asylum.

Recent arrivals in Uganda continue to speak of barbaric violence, with armed groups reportedly burning down houses with civilians inside, killing people in front of family members, sexually assaulting women and girls and kidnapping boys for forced conscription. The conflict is deepening and there is little hope of a resolution.

Challenges

The scale of forced displacement poses enormous challenges for the international community. Forced displacement has been on the rise since at least the mid-1990s in most regions, but in recent years it has increased at an alarming rate. The reasons are threefold: situations that cause large refugee outflows are lasting longer (for example, conflicts in Somalia and Afghanistan are now into their third and fourth decades, respectively); new or reignited crises are occurring frequently (Burundi, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen and others); and the rate at which solutions are being found for refugees and internally displaced people has been decreasing since the end of the Cold War.

The staggering number of displaced people presents a monumental challenge for agencies and aid workers attempting to respond to basic assistance and protection needs. As in previous years, the humanitarian needs in 2016 outpaced the funding support for humanitarian assistance. The gap is growing between funding requirements and resources made available by donors.

Uganda is a case in point: As thousands of refugees pour into the country, the amount of humanitarian aid UNHCR and its partners can deliver increasingly falls short. In Uganda, $674 million was needed for South Sudanese refugees in 2017, but only 21 percent of that total had been received by August.

The shortfall significantly impacts the ability to deliver life-saving aid and basic services. Food rations were cut across settlements in northern Uganda, and health facilities were severely overstretched. Schooling is also impacted. Class sizes often exceed 200 students, with some lessons held outdoors. This situation is similar in many refugee and displacement camps around the world, despite significant increases in support by donors.

The shortfall significantly impacts the ability to deliver life-saving aid and basic services. Food rations were cut across settlements in northern Uganda, and health facilities were severely overstretched. Schooling is also impacted. Class sizes often exceed 200 students, with some lessons held outdoors. This situation is similar in many refugee and displacement camps around the world, despite significant increases in support by donors.

Traditionally, durable solutions include voluntary repatriation, resettlement to a third country and local integration. With little hope for a durable solution, a growing number of refugees remain in precarious situations. While the number of refugees returning to their countries of origin increased in 2016, the total global refugee population that returns home has stagnated at about 5 percent since 2013. That’s because the number of new refugees exceeds the number of returnees, a phenomenon attributed mainly to the absence of conditions conducive to a safe and voluntary return.

Resettlement to a third country is sought as a solution for refugees who have specific needs that cannot be met or who face risks where they are. Resettlement is also an important way countries can demonstrate solidarity and a sense of shared responsibility with countries hosting large refugee populations. During 2016, UNHCR referred 162,600 refugees for resettlement. Syrian refugees were the largest population benefiting from resettlement (63,000 people), followed by those from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq and Somalia. This was the greatest number of resettlements in two decades. And yet, resettlement remains a solution for less than 1 percent of refugees globally. Global resettlement needs in 2017 exceeded 1.19 million people, according to the UNHCR, far outpacing resettlement options.

As a result, an increasing number of refugees remain in protracted situations, which is defined by the UNHCR as 25,000 or more refugees from the same country of origin living in exile a minimum of five consecutive years. Based on this definition, two-thirds of all refugees were in protracted refugee situations at the end of 2016. Of these, about 4.1 million had been refugees for more than 20 years.

Many face obstacles to self-reliance. With limited freedom of movement beyond the camps, and few options for employment, they are left to depend on humanitarian assistance, which is not sustainable. Refugees need opportunities to thrive and to join the communities that host them. A shift toward removing obstacles to self-reliance is required, along with policies that enable refugees to work legally and live among the local population — policies that benefit refugees and host communities alike.

The Way Forward

In recognition of these challenges and the need for comprehensive approaches, in September 2016 the U.N. General Assembly adopted the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, a set of commitments to enhance the protection of refugees and migrants. The declaration represents a milestone for global solidarity with refugees. The U.N. recognized the unprecedented level of displacement, affirmed the rights of refugees, and committed to enhancing the protections and durable solutions available to them as provided by the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

Particularly important in the declaration is the commitment to shared responsibility for refugees, the idea that the countries and communities hosting large refugee populations should be supported by the international community. The declaration makes a strong statement of international commitment to shared responsibility for hosting and supporting the world’s refugees: “We underline the centrality of international cooperation to the refugee protection regime,” the declaration states. “We recognize the burdens that large movements of refugees place on national resources, especially in the case of developing countries. To address the needs of refugees and receiving States, we commit to a more equitable sharing of the burden and responsibility for hosting and supporting the world’s refugees, while taking account of existing contributions and the differing capacities and resources among States.” This commitment now serves as a basis for mobilizing a more effective — and more predictable — response when large movements of refugees occur.

What’s New?

The New York Declaration marks a paradigm shift in how the international community responds to refugees. It calls for a whole-of-society approach to refugee situations that includes national and local authorities, international organizations, international financial institutions, regional organizations, regional coordination, civil society partners, faith-based organizations, academia, the private sector, the media and the refugees. It explicitly envisions support for host countries and communities, recommending — in addition to adequate financial resources to cover humanitarian needs — a more robust delivery of essential services and infrastructure for the benefit of host communities and refugees, and greater resources for governments and service providers to relieve the pressure on social services.

At the international level, development actors from the government, the private sector, or from civil society operating at local, district, national and global levels will work side by side with humanitarian agencies from the beginning of a refugee influx. Establishing development funding mechanisms for hosting countries and extending finance lending options to those countries are measures recommended in the declaration.

The declaration also envisions an expanded role for refugee resettlement and complementary pathways for admission. Additionally, it charts new ground for strengthening the international governance of migration and encourages the development of the Global Compact for Safe, Regular and Orderly Migration.

Comprehensive Framework

For large refugee situations, the New York Declaration includes the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), which calls on and serves as a guideline for the UNHCR to “develop and initiate” comprehensive responses in different refugee hosting countries and regions. With governments in the lead, the UNHCR’s role is to act as a catalyst in this process. The lessons learned will feed into the development of the U.N.’s Global Compact on Refugees.

Djibouti, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda have agreed to apply the CRRF. It is also applied in Somalia, requiring the involvement of Somalia’s government and its neighbors in a regional approach. Mexico and countries in northern Central America — Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras — are also implementing a comprehensive regional protection and solutions framework to address forced displacement issues in the region.

The CRRF’s adoption in the roll-out countries is progressing at a good pace. National road maps have been formulated that define short- and long-term priorities, key gap areas in the international response have been identified and additional actors have been recognized, along with novel forms of engagement. Some of these roll-out countries have reviewed and adapted their refugee policies and legal frameworks, and are moving away from encampment and toward policies that allow for greater movement by refugees, paving the way for greater refugee self-reliance. To maximize results, these countries require additional financial support and innovative partnerships.

The whole-of-society approach is a fundamental element of the CRRF: It means to support governments by bringing a wide range of national and subnational authorities on board. This includes those who plan for and decide on the national and subnational delivery of services in essential sectors, such as health and education.

Beyond government partners, the whole-of-society approach calls for the participation of national and international civil society. That includes faith- and community-based organizations; international, intergovernmental and regional organizations; international financial institutions; development partners; the private sector; academia; and the refugee and host communities. As part of the CRRF, a new partnership has been developed with the World Bank involving a major program for refugees and host communities that will play an important role in collaborating with governments.

A Global Compact

The New York Declaration gave the UNHCR the task of building upon the CRRF to develop the Global Compact on Refugees. The UNHCR will develop this compact in consultation with governments and other stakeholders for presentation to the U.N. General Assembly in 2018.

This compact provides a unique opportunity to strengthen the international response to large movements of refugees, both in protracted and new situations. Its key objectives include easing pressures on countries that welcome and host refugees, investing in and building the self-reliance of refugees, expanding access to resettlement in third countries and other complementary pathways, and fostering conditions that enable refugees to return voluntarily to their home countries.

It is envisioned that the Global Compact on Refugees will have two parts: The already agreed upon CRRF, and an action program that will draw upon lessons learned and good practices from around the world. The action program will provide a blueprint that ensures refugees have better access to health care and education, and that opportunities for a better quality of life are available in their host communities. It will also set out tangible ways host governments can be supported through responsibility-sharing when faced with large movements of refugees.

The New York Declaration provides a “once-in-a lifetime opportunity to enhance refugee protection,” according to UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner Volker Turk. Now it needs to be seized upon and brought to bear by all stakeholders.

Comments are closed.