Maintaining cohesive societies and countering false narratives

By Rosław Jezewski

Recent years have seen a significant increase in displaced people, primarily due to conflicts, sectarian violence and environmental changes. In 2016, there were 40.3 million internally displaced people (IDPs) worldwide and 22.5 million refugees, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre’s “2017 Global Report on Internal Displacement.” Most fled to Europe. Yet, because of Europe’s aging workforce, labor and skill shortages are expected to challenge the European Union’s employment and economic growth prospects over the next four decades. For instance, an estimated 19 million fewer people will be in the EU workforce between 2023 and 2060.

In that context, migrants can make important economic contributions when they are integrated into the receiving population in a timely manner, starting with education and continuing into the labor market. If left alone, migrants are likely to face periods without realistic prospects for a durable solution. Refugees are more exposed in urban settings, where it is difficult to assist and supervise them and to monitor their possible interaction with extremist groups. In a 2015 paper for the Geneva Centre for Security Studies, Christina Schori Liang wrote that radical groups are targeting young, vulnerable men in environments such as refugee camps.

These factors will affect the cohesion and resilience of many countries and create permissive environments for hybrid threats and derogative messaging. To prevent genuine refugees from becoming vulnerable to radicalization and hostile propaganda, it is essential to provide a full spectrum of counterradicalization responses.

These factors will affect the cohesion and resilience of many countries and create permissive environments for hybrid threats and derogative messaging. To prevent genuine refugees from becoming vulnerable to radicalization and hostile propaganda, it is essential to provide a full spectrum of counterradicalization responses.

This process, to be successful, should start well before opening the borders. But how long before? This article introduces a model for the acceptance and integration of immigrants into a society while maintaining the societal cohesion of the receiving nation. This model engages the receiving country on three levels: national (requiring cooperation among government agencies), local (i.e., districts/communities), and familial (people bonding with family first, then neighbors, friends and others).

How it can work

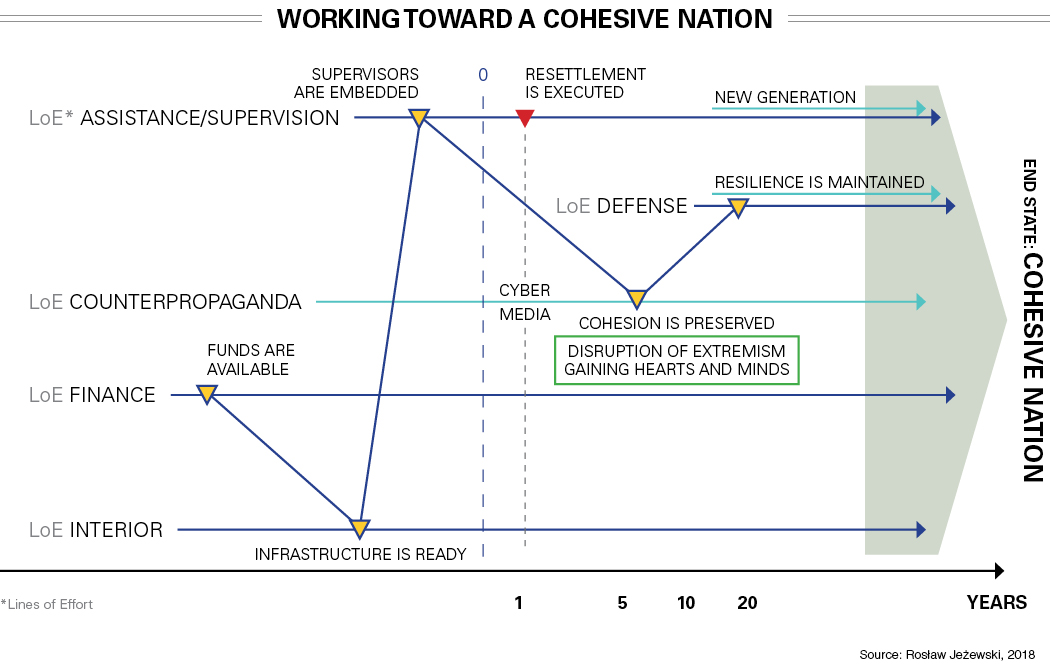

The process of receiving immigrants/refugees/asylum seekers is presented on the chart below. The vertical line labeled “0” marks the moment when the immigrants start their journey into a receiving country. Also, there are five “Lines of Effort” (LoE): Ministry of Finance (MoF), Ministry of Interior (MoI), Counterpropaganda, Defense and Assistance/Supervision. As a whole, they reflect the way the country prepares for newcomers. For example, the ministries of Interior and Finance LoEs need to start their activities much sooner than, for example, the LoE providing assistance and supervision. And they all have respective “Decisive Points” (yellow marks): MoF — when the required funds have been accumulated; MoI — when the infrastructure (housing) is ready; Assistance/Supervision — when the required personnel have been educated and employed; Counterpropaganda — when the cohesion of the nation has not been undermined by the derogative propaganda; and Defense — when the population of the country is so cohesive that it can recover quickly after an unexpected impact. The following paragraphs offer insights into how these LoEs might function.

Ministry of Interior

The MoI would carry the main burden of providing a soft landing for migrants in their new country. It will be critical to the integration process because placing the newcomers into refugee/immigrant camps is to be avoided. Ideally, migrants would go directly from their countries of origin into a small, compact society such as a village or small town. Designated communities would receive a set, but limited, number of families and children.

The MoI would be responsible for:

- registration

- public administration

- emergency management

- support for local administration

The MoI would also be responsible for providing accommodation and care for new arrivals by coordinating the activities of local administrations. The desired path would incorporate the “sustainable livelihoods approach” for developing resilient communities in which all groups coexist and create a unified society.

This comprehensive approach, if introduced properly and supported by the refugees, would allow for smooth integration while helping maintain the cohesion of the receiving society and reduce the risk of radicalization among the refugees. For example, in the West the Islamic State is targeting people from diasporas who have never acclimated and who have been exposed to Islamophobia. According to the 2018 Rand Corp. report, “Russian Social Media Influence: Understanding Russian Propaganda in Eastern Europe,” mitigating the risk of radicalization among refugees goes beyond providing humanitarian assistance — it requires an approach that lets refugees make decisions about their future.

Ministry of Finance

Funding immigration personnel, infrastructure, financial assistance, refugee care and administration/supervision requires money, and these financial needs should be planned for in advance. The MoF would manage the flow of funds so that the system has the potential to operate smoothly.

It is necessary to plan well in advance all issues related to accepting migrants, such as hiring personnel in local communities and acquiring and preparing infrastructure. The MoF may also be involved in assisting immigrants/refugees by helping them send monetary remittances back home — for example, many families in Africa depend on remittances sent from emigrant children or spouses in Europe, according to the International Organization for Migration.

Assistance/Supervision

Irregular migration can be perceived in receiving countries as a threat to culture, the economy and internal security, according to the book Fortress Europe?: Challenges and Failures of Migration and Asylum Policies, edited by Annette Jünemann, Nikolas Scherer and Nicolas Fromm. Therefore, it seems necessary for a host country to execute a robust media campaign and comprehensive preparations for the arrival of its future citizens. To this end:

- Host countries should assign professionally educated personnel to assist each family/group of families for a projected period of time.

- Immigrants should not be concentrated together.

- Newcomers should be assisted in everyday life, such as dealing with administrative issues; for example, applying for official identification.

- Migrants of working age should be interviewed for job preferences and qualifications.

- Heads of families should sign a contract declaring that they will obey national laws, with a resettlement clause for those who violate the agreement.

- Migrants with sufficient language skills will be offered employment.

As these points make clear, the desired end state of the assistance process is that refugees merge into their new societies without sanctuary locations such as shelters or refugee centers and that economic assimilation is successful. This is mentioned by David Miliband in his book Rescue – Refugees and the Political Crisis of our Time. Miliband cites the four keys to successful integration: Get people employed, integrate housing, don’t ghettoize immigrants, and underscore the importance of learning the local language and culture.

However, a clear and unfiltered picture of the situation is necessary, especially regarding antagonistic groups of immigrants. This is where supervision is crucial. Existing literature highlights three conditions that foster radicalization to violent extremism in refugee camps: poor education, especially where the gap is filled by extremist religious indoctrination; lack of work; and the absence of freedom of movement. These three conditions are prevalent in many of today’s underresourced and overcrowded IDP and refugee camps, and the risk increases the longer such situations continue. Equally, they point toward intervention opportunities that may reduce the risk of violent extremist radicalization in such settings: Somebody who does not want to live peacefully, or disseminates radicalization propaganda, should be removed/resettled. By doing so, the receiving country will protect the host nation and its citizens, maintain societal cohesion and inhibit the spread of radicalization propaganda.

Case studies

Case Study I: Fake news — the “Lisa” case

In 2016, a Russian-born 13-year-old girl claimed that she was raped in Berlin by asylum-seekers, sparking huge protests from Germany’s large Russian community. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov accused the German government of trying to cover up the incident, but it was later determined that it was an act of Russian propaganda. This incident is a perfect example of how migration can be used to create false propaganda. In a 2017 paper on migration and propaganda for the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung in Budapest, Attila Juhász and Patrik Szicherle wrote:

“The topic of migration also has geopolitical significance. It is exploited and used by anti-immigration and pro-Russian propaganda to support the Kremlin’s geopolitical objectives. Pro-Russian propaganda media is in large part responsible for the dissemination of migration-related fake news, which fits the pattern of anti-immigration propaganda in general and represents Russian interests in particular. The topic of migration is suitable to disrupt European unity and shake EU citizens’ confidence in European institutions. Fake news and anti-immigrant propaganda underpin the European far right’s political vision on immigration: cultural war, the impossibility of integration and all immigrants being public security threats are all views featured both in anti-EU parties’ rhetoric and the articles on pro-Russian propaganda sites.”

Case Study II: Syrian refugees

In September 2016, authorities in Germany arrested a 16-year-old Syrian refugee for planning to carry out a terrorist attack. He was arrested at a refugee center near Cologne, where he was living with his parents since fleeing the civil war in Syria in 2015. The authorities discovered bomb-making materials and evidence of internet chats with ISIS members. An investigation revealed that this boy was a perfect example of radicalization through propaganda: He was lonely, with no friends/relatives at the refugee center. Through frequent internet browsing, he was exposed to and poisoned by jihadi propaganda.

Countering adversarial narratives

The primary objectives of counterpropaganda are to win immigrants’ hearts and minds and to disrupt extremist propaganda, which together help create conditions conducive to societal cohesion and resilience.

It’s no surprise that terrorist groups use cyberspace and the dark net to spread vicious propaganda, but the latest trend has become a serious headache for security services. ISIS, which has mastered online applications, now uses the secure Telegram app to convey hostile propaganda, making it difficult to track by counterterrorism officials, Joby Warrick wrote in The Independent.

Efforts to censor and remove extremist messaging have proven ineffective, because radical propaganda is still present in the media. This battle must be fought by other methods:

- Disruption — preventing the propaganda from reaching the target audience, especially in social media. To be effective, this must be executed in a comprehensive manner, not leaving empty space that can be exploited by radical groups. To effectively prevent radicalization of migrants and refugees, disruption should start before they reach the host country.

- Redirection — redirecting users to websites that counter or discredit extremist messaging.

- Campaign and message design — providing backup to nongovernmental organizations to create campaigns undermining hostile propaganda.

- Synchronizing government messaging and action — messages that relate to everyday life and actual events increase societal trust in government and its actions.

Knowledge of the target audience is crucial and determines the course of a campaign. For example, a government campaign oriented to young immigrants will not be the same as a campaign directed at returning foreign fighters.

Conclusion

Giulio Meotti of the Gatestone Institute asserted in a 2016 report that Europe will be unrecognizable in one generation. Does that mean demographic trends will shape the global security situation in coming years? Most probably, yes. It is the governments and people of the destination countries that will decide how to prepare for the newcomers. Immigrants with different backgrounds — or returning foreign fighters — will hardly be able to communicate. Many are unwilling to integrate with the receiving population and disobey the law. Samuel Huntington, in his book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, quoted his colleague Myron Weiner: “Westerners increasingly fear that they are now being invaded not by armies and tanks but immigrants who speak other languages, worship other gods, belong to other cultures and, they fear, will take their jobs, occupy their land, live off the welfare system and threaten their way of life.”

If radicalized, they can be directed into hostile attacks, and their presence can be used to disrupt a nation’s unity. Also of concern is that hostile migrants from adversarial nations or nonstate factions could spark conflict in a receiving country. The “Lisa” and “Syrian refugee” cases are evidence that this potential “weapon of mass migration” is powerful and can be activated from afar or from cyberspace. R.T Howard is his article “Migration Wars” in The National Interest magazine stated that migration has been weaponized — and can itself become the cause of war and destabilize whole regions. This drives home the point that the immigrants’ desire to obey the law, and integrate into society, is crucial. Without this, the efforts of the receiving countries can be wasted, and many people can be hurt.

This model of accepting migrants into a host country is not perfect, for sure. It deliberately formulates questions without clear answers. But it clearly states that efforts to preserve the cohesion and resilience of a nation are paramount when facing migration.

Comments are closed.