China seeks to undermine democracy, acquire new technology and quash dissent

By Theresa Fallon, director, Centre for Russia Europe Asia Studies

Shi Pei Pu was a Beijing opera singer and spy whose perplexing liaison with French diplomat Bernard Boursicot was one of the odder cases of espionage and inspired a Broadway play. Their trysts were always in the dark, which Boursicot attributed to Chinese modesty. Shi, who was a man posing as a woman, even presented a child, whom he claimed was their offspring. This ruse was designed to coax Boursicot to continue to pass French embassy documents to officials of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Boursicot’s 20-year affair with Shi started in 1964. When he learned in 1983 that Shi was a man, Boursicot sliced his throat with a razor blade while in prison in a failed attempt to take his life. The record does not indicate if this was the first time a French official should have been less naive about the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), but the tradition continues.

Although almost all nation-states spy and seek influence, the scope and intensity of the PRC’s activities are overwhelming both in the United States and in Europe. FBI Director Christopher Wray testified before a U.S. Senate panel in 2021 that his agency opened a new China-related counterintelligence investigation in the U.S. every 12 hours on average, and that it had more than 2,000 such cases. Smaller intelligence services in Europe are confronted with a rising tide of influence cases and lack the language and regional expertise needed to effectively respond.

In the post-Cold War period, the PRC was not perceived as a threat because of the “end of history” mindset that asserted free-market economics would inevitably lead to democratization. In Germany, Wandel durch Handel — “change through trade” — was first used to describe the country’s trade approach toward Russia and then was repurposed for the PRC. What it did not anticipate was that increased trade with authoritarian regimes would introduce dangerous dependence and import corruption as well. Business interests and financiers lobbied on behalf of Beijing and eventually the PRC entered the World Trade Organization, which turbocharged its economy.

Belgium, which is home to NATO headquarters and most EU institutions, is a prime PRC influence target. Even though the Belgian State Security Service (VSSE) has increased the number of its staff to about 1,000, it continues to be challenged in monitoring ever-expanding foreign interference operations, especially from China and Russia. Compare this number with the PRC’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) department in Zhejiang, their center for European operations, with an estimated 5,000 intelligence officers.

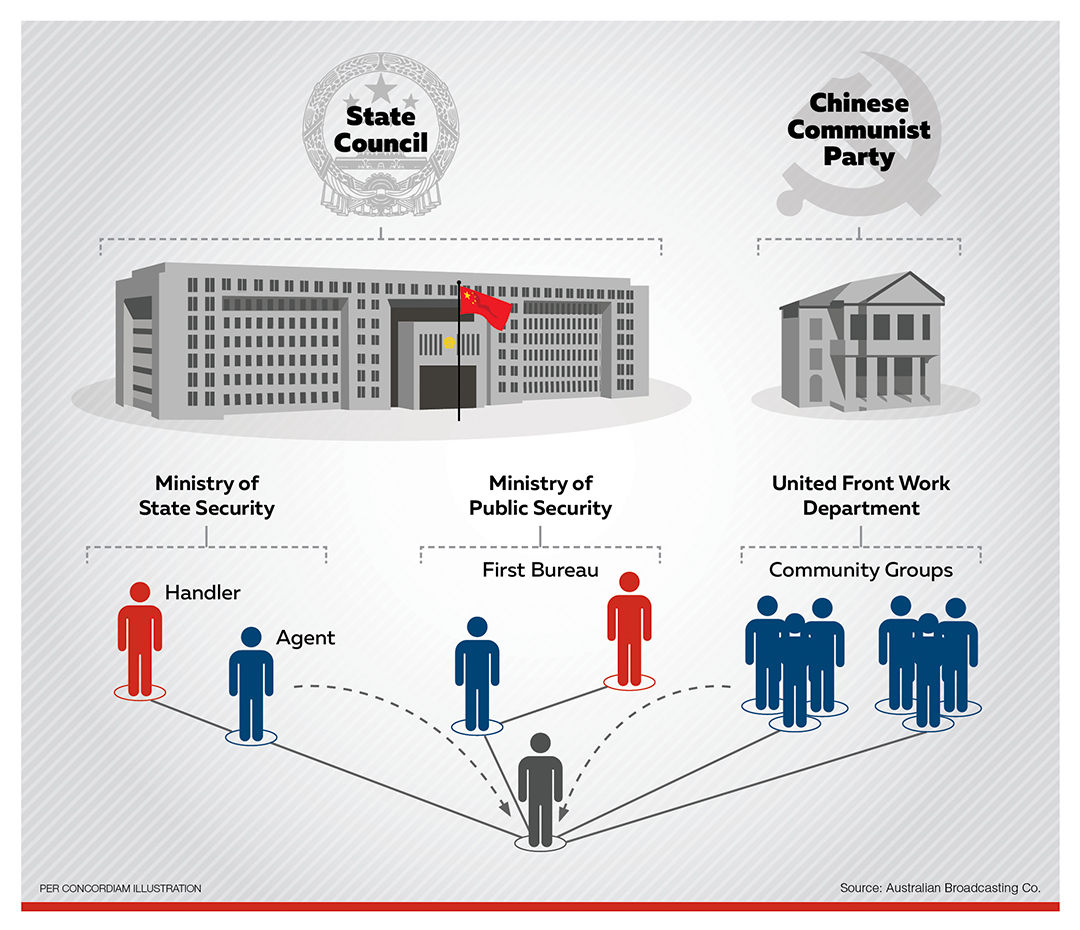

At the time of this writing, the latest case concerned a Chinese aide to Maximilian Krah, a member of the European Parliament from the far-right Alternative for Germany party. The aide, Guo Jian, was arrested by German police on charges that he had been passing information about the European Parliament’s deliberations to China for years. He was also thought to be monitoring the Chinese diaspora community in Dresden. Such activities are often the work of the CCP United Front Work Department (UFWD).

United Front work

United Front is a particular mix of engagement, intelligence operations and influence activities. The CCP uses these levers in its attempts to influence other countries’ policies toward the PRC, drive wedges into Europe and gain access to advanced foreign technology. United Front is often combined with intelligence and other foreign interference.

The concept of “united front” was launched by the Third Communist International in Europe in 1921 and later exported to China, where it took on a life of its own. In 1939, Mao Zedong called it one of the three “magic weapons” for defeating the rival Kuomintang (the other two weapons being the party itself and the People’s Liberation Army). United front essentially means enlisting as many social actors as possible to pursue the interests of the CCP, both at home and abroad. The actors enlisted to work in the interest of the party are mainly Chinese citizens or people of Chinese origin.

The Party Central Committee established the UFWD in 1942. The Cultural Revolution shut it down and Deng Xiaoping reopened it in 1979. Xi Jinping strengthened the department through an internal reorganization of the party apparatus from 2015 to 2018. Xi also established a Central United Front Work Leading Small Group of senior party figures to coordinate the work of agencies active in this area.

Of the department’s 12 bureaus, most have a domestic focus, but one concerns Hong Kong and Taiwan, and two concern overseas Chinese. People of Chinese origin who live abroad usually maintain links with their home country and draw their information from PRC media that reflect the vision of the CCP. In some cases, the PRC bought Chinese-language media outlets in Europe. This makes it easier for the UFWD to recruit overseas Chinese as agents.

The UFWD works for the long term, even though its future returns may be uneven and unpredictable. The party’s agents of influence seek incremental changes over time that shift the strategic landscape without others even noticing. The goal is that investment in influence activities will reap dividends over time. Some of the tools used by the department to co-opt individuals and spread the CCP’s influence abroad are associations of the Chinese diaspora in Europe, chambers of commerce and other business associations. Authorities in Europe have awakened to the threats posed by United Front to social cohesion and democratic politics, and to the risk that it facilitates espionage.

For instance, in January 2022, the United Kingdom’s domestic counterintelligence agency MI5 issued an “interference alert” on Chinese-born U.K. subject Christine Ching Kui Lee, who “knowingly engaged in political-interference activities on behalf of the United Front Work Department (UFWD) of the Chinese Communist party.” It warned that the UFWD was “seeking to covertly interfere in U.K. politics through establishing links with established and aspiring parliamentarians across the political spectrum.” It accused Lee of having “facilitated financial donations to serving and aspiring parliamentarians on behalf of foreign nationals based in Hong Kong and China” through the Chinese in Britain’s All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG). It was the first time that MI5 issued this type of alert involving China. It had issued previous alerts regarding Russia.

Authoritarian co-option in Europe

One of the main goals of Chinese influence operations in Europe is authoritarian co-option — persuading European public figures to have a positive regard for the CCP and speak favorably about its domestic policies on Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet, and on external policies such as the South China Sea. These like-minded surrogates are then invited to speak as proxies to promote the CCP’s positions. These proxies also are used to buttress the CCP’s narrative domestically to demonstrate the party’s international standing, influence and support. This CCP-created echo chamber carefully curates a positive and uniform storyline for both domestic and international audiences.

China’s authoritarian co-option works best in permissive political environments such as in Europe. The key areas the party seeks to influence are at the nexus of society and politics because these areas lack oversight, are open to foreign participation and are largely unregulated. The CCP uses the openness of European societies, and their rights of free speech, to promote authoritarian messages that are antithetical to Europe’s own values and interests. Captured elites can openly lobby political bodies, businesses and decision-making institutions on behalf of the party. This reinforces the CCP’s chosen narratives for both domestic and international audiences.

The CCP’s efforts are calculated to co-opt specific groups or individuals such as politicians, retired military, academics, chambers of commerce, and distinct social and ethnic groups to tell China’s story. These narratives range from glossing over China’s history, deliberate distortions of China’s human rights record, and reinterpreting international law to suit Beijing’s territorial claims.

Nationalist Belgian politician Frank Creyelman is a case in point. In December 2022, three of Europe’s leading newspapers — Financial Times, Der Spiegel and Le Monde — unmasked Creyelman as a Chinese agent in a joint investigation. It was reported that Creyelman also operated in Poland and Romania. Creyelman’s handler, “Daniel Woo,” worked for the Zhejiang branch of China’s MSS spy agency.

The MSS directed Creyelman to influence discussions in Europe on issues that included Beijing’s push to isolate Taiwan, their heavy-handed approach to Hong Kong and Uyghur “reeducation” camps in Xinjiang. Phone messages from Creyelman’s MSS handler provided a blueprint of how Beijing conducts influence operations to manipulate people and to attempt to shape political outcomes. Such operations are often opaque, but these messages offered tantalizing insights into Beijing’s attempts to influence perceptions of the PRC using their intelligence assets, and to shape debate.

The CCP’s main goal, as texted by the MSS spymaster, was to “divide the U.S.-European relationship.” The investigation revealed that before German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s trip to Beijing in 2022, the MSS officer pushed Creyelman to persuade two right-wing members of the European Parliament to announce that the U.K. and the U.S. were weakening European energy security.

Creyelman, a former Belgian senator, was a CCP intelligence asset for more than three years. Some Belgian officials said they had known about Creyelman’s activities since 2018 but there were no laws under which they could prosecute him. Because espionage and foreign interference are not considered criminal offenses under Belgium’s penal code, which dates from 1867, they may try him on corruption charges.

In contrast to Belgium’s lack of espionage laws, the U.K.’s National Security Act 2023 updated and introduced new offenses related to espionage, sabotage, foreign interference and influence. In addition, it granted police expanded powers of arrest and detention. The new legal approach appears to be working. In May 2024, Christopher Cash, a former parliamentary researcher, and Christopher Berry, an academic, were charged under the National Security Act of passing secrets to China. Cash had worked for a China policy group linked with then-U.K. Security Minister Tom Tugendhat. Both had previously lived and worked in the PRC. At the time of this writing, the trial is ongoing.

Controlling and utilizing the diaspora

Huaqiao and huaren are the terms used to describe Chinese who live outside the PRC; huaqiao refers to Chinese citizens living abroad, and huaren refers to ethnic Chinese with foreign nationalities. Xi sees both groups as “members of the great Chinese family” who would “never forget their homeland China” and “never deny the blood of the Chinese nation in their bodies.” In other words, the CCP sees affiliation to the PRC not in terms of legal citizenship but rather in ethnic and racial terms. Ethnic Chinese outside of the PRC are seen as possible tools to help mobilize support and advance Beijing’s interests. Clearly, not all members of the Chinese diaspora agree with Beijing’s approach.

In May 2024, a compelling Australian investigative TV program called “Four Corners” conducted the first interview ever of a former (self-described) member of the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) First Bureau, the notorious Chinese secret police. Previously, he belonged to the unit called the Political Security Protection Bureau. The unit is one of the CCP’s key tools of repression. It operates around the globe to surveil, silence and summon critics of the party and then return them to China.

Basically, anyone in the Chinese population at home or abroad who threatened the CCP’s control would be investigated, opposed and disrupted as necessary. As noted earlier, the CCP’s main foreign influence organization is the UFWD. The MPS First Bureau works with Beijing’s state security apparatus when necessary. As one former CIA analyst summed up the relationship: “United Front work creates tall grass to hide the snakes. The MPS are some of those snakes.”

Operation Fox Hunt

Operation Fox Hunt, established by Xi in 2014, is a well-funded, secretive global operation to hunt down Chinese officials suspected of corruption who have fled to other countries. One report published in May 2024 stated that 12,000 people were found in so-called “fugitive recovery operations” in 120 countries since it was established.

Not only are rich and powerful Chinese accused of corruption “persuaded” to return to China, but sometimes also those who demonstrate even the slightest form of dissent. In May 2024, before Xi Jinping’s visit to Paris, French state television broadcast a documentary on what happened to a 23-year-old Chinese national named Ling Huazhan, who lived in Paris and posted a video online criticizing Xi. Although the video had only 80 views, the PRC embassy in Paris demonstrated zero tolerance, calling Ling on the same day and telling him that he must return to China. Ling contacted a reporter, who followed him to the Paris airport. As he was escorted by several PRC diplomats to the plane, Ling fearfully stated that he did not want to go back to China and refused to board. The diplomats realized the incident was being filmed by journalists and decided to end their efforts but refused to give back Ling’s passport. Since they were diplomats, French police could not search them. Chinese officials later used threats and torture of his family in China to coerce his return. Ling received a message on his phone stating that his brother’s leg was broken and threatening to break the other along with burning his brother’s genitals if he did not return. PRC officials prefer to conduct these extraterritorial repatriations quietly, but this incident was documented by French state media and it gives a glimpse into the lengths the CCP will go to punish even minor dissent.

Overseas Chinese police stations

One of the key goals of UFWD is to control people of Chinese descent inside as well as outside of the PRC. To do this, the CCP has created a global network of clandestine “police stations” in more than 50 countries, many of them in Europe as well as the U.S. PRC officials protested that these were created to help Chinese nationals with mundane tasks such as renewing their licenses and other bureaucratic procedures. This claim doesn’t stand up as embassies and consulates are tasked with such functions. Rather, these clandestine stations were used to monitor the behavior of the diaspora and prevent activity seen as disruptive to the CCP. The secret police stations are a violation of established diplomatic norms and, once discovered, many countries have tried to shut them down. Chinese diplomatic missions abroad usually host MSS agents who are tasked with collecting intelligence. The work of these agents is not declared to the host countries. Agents also operate from the offices of Chinese news agencies and commercial companies.

‘It is futile to resist’

In May 2024, three men were charged in London with gathering intelligence for Hong Kong authorities and with a forced entry into a residence. (A trial is set for February 2025). Their arrest highlighted the CCP’s ability to harass, surveil and even physically attack activists. One of the accused, a former British Marine named Matthew Trickett, was discovered dead in a park. His death was categorized as “unexplained” by the police (a term often used to describe a suicide).

Britain’s Foreign Office stated that the accusations of intelligence gathering appeared to be part of a “pattern of behavior directed by China against the U.K.” This increased activity included the posting of bounties of up to $128,000 for information on dissidents, many of them originally from Hong Kong. The CCP’s message appears to be that wherever a member of the Chinese diaspora is in the world, they will be monitored and punished if they step outside CCP redlines.

Spies, lies and technology

As the U.S. tightens exports on advanced technologies, Beijing has increased its efforts in Europe to collect knowledge and information on such capabilities. The PRC seeks to obtain advanced technology in multiple ways: legally, through investments, and by funding research. And illegally, by using a combination of company insiders, cyber espionage, circumvention of export restrictions, acquisitions and reverse engineering of technology.

According to the Dutch military intelligence agency MIVD, in its annual report published in April 2024, CCP espionage targeted aerospace, maritime industries and semiconductor manufacturing.

ASML, the leading Dutch manufacturer of chipmaking equipment, in 2023 agreed to work with the U.S. on national security grounds to prevent advanced chipmaking technology being exported to the PRC. In April 2024, the U.S. government tried to persuade ASML not to service some of the advanced machines in the PRC. ASML repair technicians, on a previous trip to China, suspected that their advanced equipment was “broken” because it had been taken apart, likely to reverse-engineer it, and the Chinese technicians were unable to put it back together.

Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, in its most recent annual report, labeled the PRC as Germany’s “biggest economic and scientific-espionage threat.” Beijing’s key areas of interest in Germany include aerospace technology, information technology, robotics, energy-saving technology and biomedicine.

German prosecutors reported in April 2024 that three German nationals were arrested on suspicion of the unauthorized transfer of technology with military applications — including a high-powered laser — and scientific information that could be used to build advanced engines for military vessels. This case demonstrated that existing regulations were inadequate to prevent this type of prohibited export.

Controlling the information space

By law, Chinese digital technology companies that own any application are obliged to share users’ data with the Chinese authorities, which opens the door to spying. The TikTok social media app has received much attention lately, as the U.S. asked its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, to divest from the app or face a ban. Several countries around the world, including some in Europe, have banned the app from the phones of government employees, or, as in the case of India, from all phones. However, this phenomenon does not concern only individual apps but is a more general problem.

The data harvested by China from any cellphone, not just from those of government officials, helps the CCP better target its messaging according to user-data analytics, thus improving its ability to control global narratives. Popular apps, social media platforms and online games are instrumental for this purpose. A recent study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute highlighted the links between the CCP’s state-controlled propaganda entities and data-collection activities. The CCP also has legal access to any information available to a Chinese company that operates abroad.

China is now investing heavily in emerging technologies such as generative artificial intelligence (AI) and the metaverse. These will be powerful tools to advance China’s messages globally, including in Europe, testing EU regulations on the ethical use of AI. The CCP is already experimenting with metaverse-based gaming domestically, to facilitate its ideological indoctrination of the population. At the same time, China is shielding its population from outside influence through its Great Firewall, which bars access to foreign apps such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter), and through a ban of foreign games and virtual private networks.

Sino-Russian influence activities overlap

“Right now, there are changes — the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years — and we are the ones driving these changes together,” Xi confidently told Russian President Vladimir Putin as he stood at the door of the Kremlin to bid him goodbye at the conclusion of a state visit in March 2023. Some of these incredible changes are the overlaps in influence activities that target both people and organizations. Recent espionage incidents in Europe have made it a bit easier to connect the dots. If a politician is willing to spy or take a bribe from Russia, the reasoning goes, it is likely they will do the same for the PRC. Sino-Russian convergence of interests displays an unrelenting drive to challenge the West and to disrupt and corrode European democracy. The unfolding Creyelman and Krah cases provide some evidence in this regard. It seems that parliamentary assistants are a particularly good source of information, and that ex-legislators are a soft target for both Chinese and Russian intelligence and influence operations.

Enhanced Sino-Russian cooperation on influence activities should not come as a surprise. At a Senate hearing on May 2, 2024, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines testified that cooperation between China and Russia was increasing in every area. The Sino-Russian “no-limits partnership” announced in February 2022 was followed by the outbreak of war in Ukraine that same month. China must have assessed that the war is in its interest because it depletes U.S. military stockpiles and deflects attention from the Indo-Pacific. Since 2022, China increased its exports of dual-use goods to Russia dramatically while still trying to avoid U.S. sanctions on Chinese exporters.

Chinese organized crime in Europe

There is evidence that Chinese organized crime groups in Europe cooperate with China’s undeclared police officers posted to Chinese diplomatic missions to monitor and intimidate overseas immigrants and dissidents. These groups are well-rooted in the host countries and can offer intelligence and support to Chinese police. In exchange, Chinese authorities do not prosecute the gangsters who operate abroad, and never cooperate with their European counterparts when the suspects of a crime seek refuge in China. Chinese organized crime bosses are often involved in Chinese cultural associations in Europe, which in turn are affiliated to the UFWD. In Italy and Spain, local Chinese mobsters have been involved in setting up covert police stations. Similar patterns of activity have also emerged in the U.S. and elsewhere. The symbiotic relationship in foreign countries between Chinese organized crime and police and intelligence agents is a good illustration of the United Front concept.

Recommendations/conclusion

We can no longer continue down the path tread by Bernard Boursicot. Instead, to extend the metaphor, we must flip on the light switch, recognize the stubble on the Chinese opera singer’s face, and end our naivety about the PRC. This smokeless war requires not only a trans-Atlantic strategy designed for the long term but also needs to include NATO’s partners in the Indo-Pacific Four (Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea) and learn from their best practices. Australia has been at the forefront of understanding the effects of Beijing’s influence, interference and espionage efforts. Here are some recommendations:

- Europe should investigate Chinese influence operations to understand how they work, as well as to raise awareness about them so that they can be better countered and defused. United Front is often intertwined with espionage and other influence activities. This may require developing a new conceptual framework to tackle the phenomenon.

- European countries that do not yet have anti-espionage laws, notably Austria, or have outdated ones should take legislative action. This would facilitate the prosecution of Chinese intelligence agents. (Belgium’s current low-risk, high-reward espionage landscape climate is governed by laws that have not been updated since 1867.)

- European countries and the EU should support independent Chinese-language media to counter the influence of Beijing-sponsored media on the overseas Chinese population, thus reducing their willingness to carry out United Front work.

- Europe should build on its experience countering Soviet intelligence operations during the Cold War to strengthen counterintelligence capabilities and isolate Chinese assets like Belgium’s Creyelman.

- EU institutions and member states should step up their work to counter foreign information manipulation and interference.

- EU institutions and member states need to push for the “disinfectant of sunlight” and advocate for a foreign influence transparency registry.

- EU institutions should invest in Chinese language and culture education to increase knowledge among policymakers about how the UFWD operates and prepare the next generation of specialists.

Policymakers and intelligence services must innovate, educate and adapt to the changing threat landscape. A key challenge will be to ensure that the strategic response on both sides of the Atlantic will honor the ideals of freedom, openness and lawfulness. A calibrated response to Beijing’s smokeless war, coupled with constant vigilance to avoid being “Boursicoted,” will help protect democratic institutions and build resilience to the growing threat from the Chinese Communist Party-state.

Comments are closed.