The U.S. pivot to Asia forces Europe to rethink the way it projects power in the world

By Prof. Dr. Sven Bernhard Gareis, Marshall Center

In April 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama visited Japan, the Philippines, South Korea and Malaysia. His tour was intended to send a clear message: The president is serious about the pivot to the Asia-Pacific announced in 2011. There had been rising doubts about his willingness to bring about this shift in foreign policy. In October 2013, Obama had canceled a planned tour of Asia because of struggles over the United States’ budget, raising concerns about the seriousness of his commitment throughout the region, mostly from China. At the 2013 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit on Bali, the “family picture” — a photograph traditionally taken at the end of a meeting of political leaders — shows Chinese President Xi Jinping at center stage among the 21 APEC representatives, including Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Squeezed into the far right corner is U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, looking almost marginalized. Subsequently, there were calls for a more substantial U.S. involvement in Asia, not only from the Republican opposition, but from all sides.

In Europe, where hopes are high that the U.S. is not going to give up on its best ally, critical voices have called for an economic “pivot to Europe.” Faced with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, East European allies have demanded an increased U.S. military presence — something that is very unlikely to happen. During the Libya conflict in 2011, the U.S. was reluctant to take the leading role. In the Syrian and the Middle Eastern conflicts, the U.S. is also keeping a low profile. Same thing in the Ukraine crisis: The U.S. is keeping its military commitment low — also to avoid inflaming relations with Russia. Following the NATO Wales summit, there were words of reassurance for eastern NATO allies, and 18 fighter aircraft were deployed to Poland and Lithuania — not an impressive feat, considering these jets are not needed anywhere else.

One of the main reasons for Obama’s pivot to Asia may have to do with a new world order, because the days of American patronage — what U.S. commentator Charles Krauthammer called the “unipolar moment” — are over. In an accelerated process of geopolitical shifts of power, emerging actors such as China, India and Brazil started pursuing their interests with more determination and claimed their right to shape the international system with increasing self-confidence. By contrast, the incumbent world power, weakened by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and tied down by its enormous debt burden, needs to pool its resources and rely more heavily on regional partners and alliances to maintain its position of power. And, more than anything else, it needs to set strategic priorities to monitor China, which is developing fast and presents a challenge to U.S. global dominance. The U.S. has to relocate political and military capabilities from other parts of the world to the Asia-Pacific region. In this context, “America’s Pacific Century,” a term coined by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is not necessarily an expression of self-assured strength, but rather an acknowledgment that the U.S. is no longer able to exercise its hegemonic power in all regions of the world simultaneously.

Europe’s status

Even if the U.S. remains interested in a close partnership with its old allies, the pivot to Asia undoubtedly presents a challenge to Europe. But, at the same time, it offers an opportunity. For decades the “old continent” has enjoyed the comfort of regional and global security guaranteed largely by the U.S. As consumers of security, European allies were free to focus on economic development and increasing prosperity, and, on top of that, they were able to profit from the enormous peace dividend from the drastic reductions in armed forces and defense budgets after the end of the East-West conflict. The new geopolitical power shifts will force Europeans to defend their own interests, develop strategies and use the instruments required to enforce their claims. While trying to manage the Ukraine-Russia crisis, they are beginning to understand the magnitude of this challenge. In spite of weaknesses, Europe needs to overcome internal disagreements, take appropriate measures and impose effective sanctions to prevent Russia from further destabilizing Eastern Europe.

Cohesion in foreign and security policy is a requirement not only within Europe, but beyond. Europe is a global economic and trading power with close links to the Asia-Pacific region and its fast growing markets. Therefore, Europe has a vital interest in security and stability in Asia, without, however, being able to exert any political influence in the region. Europe must underpin its economic interests through more political unity and a stronger regional, as well as global, commitment to overcome a world order dominated by U.S.-China relations.

So, what does this mean for Europe’s common foreign and security policy, and what are the consequences of Europe’s future role on the stage of world politics?

The U.S. as a Pacific power

A point that tends to get overlooked when Europeans assess the state of trans-Atlantic relations is that throughout its strong commitment in Europe during the East-West conflict, during the subsequent transformation processes in the post-Soviet states and the difficult pacification of the West Balkans after the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the U.S. was always a Pacific power, too.

As a result of close economic ties with China in the early 19th century, the U.S. developed strong political interests in the region, which led to increasing political commitment and, from time to time, military commitment. Ever since the U.S. was forced into World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, it has shaped the political landscape in the Pacific region. During the Cold War, the results of this commitment were mixed: success in the Korean War (1950-53), disaster in Vietnam, extreme pragmatism in the rapprochement with China (early 1970s). All of this led to a peculiar stability characteristic of that era — power and countervailing power, and deterrence based on massive threats of force. Since the end of the East-West conflict, the U.S. has pursued a policy of flexibility and strong bilateral relations, guaranteeing enduring peace, a type of Pax Americana. The U.S. became a dominant power which, in spite of criticism, is seen as indispensable by many Pacific states. That the U.S. is considered to be a guarantor of order in the West Pacific can be explained by the “containment” of Japan — a side effect of the U.S.-Japanese defense alliance — because there is still a certain degree of distrust of Japan and its power potential in the region, and by the strong U.S. presence in the Korean Peninsula that has repeatedly kept North Korea from playing with fire.

No longer restricted by the ties of the bipolar world order, the Asia-Pacific region has become the economic powerhouse of the world, which has brought unprecedented economic growth and prosperity to the region in the last two decades. At the same time, the situation in the region seems paradoxical: The close economic ties and interdependencies among the states did not translate into any security structures that would help overcome, or at least mitigate, territorial disputes between neighbors, historical grievances, strategic rivalries and security dilemmas. This, as well as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the war on terrorism that has absorbed most U.S. forces, makes the Asia-Pacific very complex. The U.S. has not yet developed a consistent strategy for the region. Relations with China, the greatest emerging power, remain highly ambivalent, alternating between partnership and rivalry, but always characterized by interdependence.

China as a challenge

A recurring theme in U.S. official statements and documents is interest in a prosperous China that is able to solve its internal problems. But there is more to it than just interest: The rise of China is the main reason for the pivot to Asia. And indeed, carried on the wings of its continuing economic success, China has opted for a more comprehensive, self-confident, proactive and often tougher approach in its foreign policy at the regional and global level. The People’s Republic has begun to assert its interests in energy and natural resources more forcefully, pushing for access to new forums such as the Arctic Council and representing a serious alternative, especially in Africa, to the traditional donors of multilateral development aid such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. It is with growing concern that many states look at China’s increasing military spending — approximately $160 billion in 2015 — and China’s simmering disputes with Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines over groups of islands in the East and South China seas, because any confrontation in this globally connected region would have drastic consequences for Europe, too.

From a classic power-centric perspective, China is a new actor seeking to exploit changes in the structure of the international system for its own benefit and enter into competition and, possibly, confrontation with the established great powers of the current international system, above all, the U.S. In contrast, however, China presents its version of a “harmonious world,” which, as former Chinese President Hu Jintao declared in 2005 before the United Nations General Assembly, is characterized by respect for different cultures, by cooperation and by mutual benefit. His successor, Xi Jinping, keeps repeating that cooperative solutions are needed to solve international problems. With its concepts of “peaceful development” and a “harmonious world” China claims an exceptional role for itself by choosing methods and pursuing strategic goals that are different from what many Western actors see as standard behavior in international relations.

The U.S. is China’s most important trading partner, the largest consumer of Chinese products, and is essential for China’s strong export-oriented industry. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, China has consistently invested its gigantic trade surplus in U.S. bonds, about $295 billion in 2013, out of an overall trade volume of nearly $530 billion. This is how China helps finance U.S. budget deficits and keeps the U.S. banking system solvent so that banks can continue granting credit to customers who will then be able to keep buying Chinese goods. On the other hand, both countries are openly distrustful of each other when it comes to power interests. The U.S. sees China as the only serious challenge to its global dominance. China, in turn, is concerned that the U.S. might slow down or even disrupt its economic growth and assumes that the pivot to Asia is nothing but a poorly disguised attempt to contain China.

Indeed, this concern does not appear to be completely unfounded. At the 2010 Regional Forum of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Vietnam, Clinton declared that a multilateral solution to the territorial dispute in the South China Sea was in the national interest of the U.S. This statement touched a sore spot with the Chinese, who felt that their sovereign rights were disregarded. Obama’s announcement in November 2011 that the U.S. will permanently station Marines in Australia, starting with 2,500 troops, and his decision to keep two-thirds of all U.S. carrier battle groups assigned to the Pacific, alarmed Beijing. And when he stated during his visit to Tokyo in April 2014 that the U.S. would not interfere in the Sino-Japanese dispute about the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, but that it would support Japan on the basis of the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement if the dispute escalated into a conflict — Obama’s message was perceived as highly ambiguous by China. The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement that was concluded with the Philippines shortly afterward permits the U.S. to use Philippine military bases. The People’s Republic sees this as an example of hedging against China, as it does the Trans-Pacific Partnership proposed by the U.S., a free trade agreement that will include most Pacific states, but not China.

China’s role in the U.S. rebalancing process was the subject of a detailed analysis by David Lai and Steven Camaron, who, with good reason, conclude: “Chinese leaders had just two options for interpreting these statements. They could have either naively assumed that the United States would execute a costly foreign policy initiative in the region without choosing to put special focus on the region’s most influential member, or they could have more logically assumed that the United States was making plans to impede China that it desired to hide. By refusing to acknowledge that China’s rising prominence was what made the region more deserving of U.S. attention, the administration appeared hostile and deceitful despite its peaceful promulgations. This rhetorical mistake closed many doors to peaceful negotiation and has contributed to the region’s growing polarization.” This could lead to a dangerous situation with all the prerequisites for a substantial security dilemma.

The U.S. should employ political and diplomatic finesse if it wishes to stage a powerful return to the Asia-Pacific. For some time, Washington has been under pressure from strong nationalist movements ― not only in China, but also in Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and the Philippines ― concerning disputes over islands of mostly symbolic value in the South and East China seas. If the U.S. wants to play a stabilizing role in the region, it will have to exert a moderating influence on its allies and not encourage them, even indirectly, to provoke China in those disputes, which could possibly trigger reactions that cause more harm. Acts of defiance by China such as setting up an Air Defense Identification Zone over the East China Sea at the end of 2013, or the stationing of an oil rig in coastal waters claimed by Vietnam in May 2014 result from a position of insecurity. China realizes that such acts of aggression will not lead to sustainable results because it lacks the capabilities to enforce them over long periods, which means that, in the end, they are counterproductive and harmful to its long-term interests.

The relationship between the U.S. and China, often seen as the most important one of the 21st century, is a perfect example of interdependence, with all the opportunities and risks involved. A situation like this requires both sides to step cautiously and use their power with consideration to allow a smooth transition from Pax Americana to a stable regional order based on constructive cooperation. This would not only benefit a region not interested in power games between the U.S. and China, but would also accommodate the Europeans, who have many economic interests in the Pacific region but very little political leverage.

Implications for Europe

What does all of this imply for Europe? The first question that comes up in this context is whether there is such a thing as a common perspective in the global concert of powers. The European Union is without doubt a global economic power whose 28 member states account for more than a quarter of worldwide economic output. But is the EU politically more than the sum of its parts? Does it pursue a common policy? Does it act coherently as a great power in the international arena? There is room for doubt because in its external relations and in the great game, Europe is more of a potential power than a real power. This is true of its relations with the U.S., but, even more so, of its relations with China.

Europe has long become accustomed to and felt comfortable with the U.S. playing the role of “European Pacifier,” as Josef Joffe once expressed it so aptly. Therefore, the exclusive nature of the trans-Atlantic link has always been more in Europe’s, and particularly in Germany’s, interest and has not reflected the real challenges the U.S. has been confronted with as a global power. Nevertheless, the ties to the old continent have always been strategically important to the U.S. because of similarities in political culture and shared values, interests and worldviews. Therefore, the U.S. is going to remain a European power, although at a reduced level of commitment. So when the U.S. decided to focus more on the Asia-Pacific region, Europeans remained calm and matter-of-fact. The pivot to Asia has been a gradual process rather than an abrupt fundamental change, and in view of the global power shift and the emergence of states like China, it seemed the right thing to do and was to be expected.

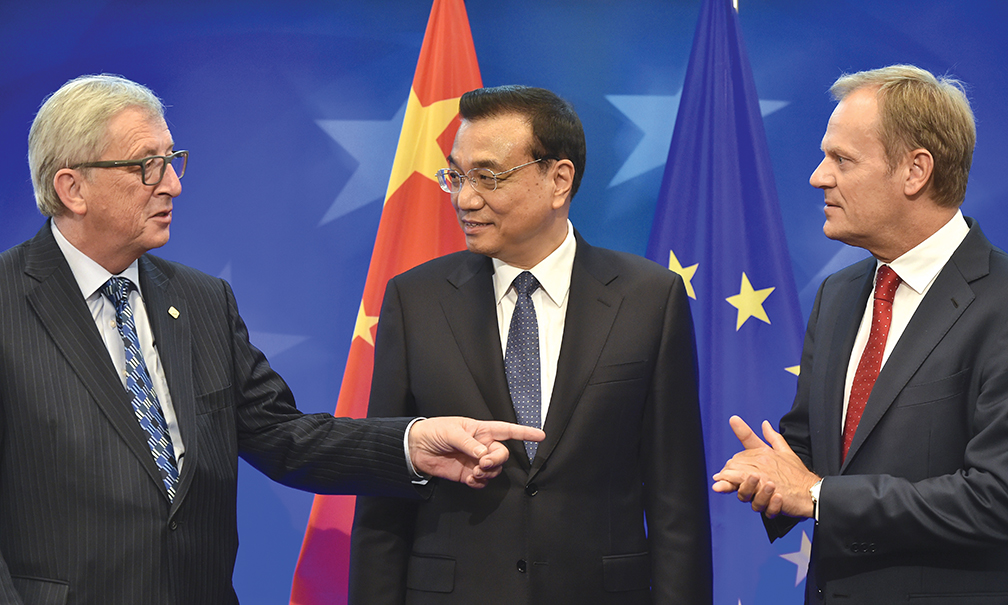

As far as Asia, and in particular, China are concerned, Europe’s interest in the region is great; its political influence, however, is low, although the EU is a dialogue partner in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum. At the Asia-Europe Meeting, EU representatives meet with those from all important East and Southeast Asian states. In 2004, the EU entered into a strategic partnership with China; there is the EU-China Summit as an established forum for regular consultations between high-ranking officials from both sides. The EU-China Dialogue on Human Rights was set up in 1997, consisting of a dense network of more than 50 expert dialogues on matters from economic and social issues to cooperation in customs matters.

However, the People’s Republic can at any time cancel EU-China dialogues and summits at its discretion, reduce their number (since 2012 the Dialogue on Human Rights has been held only once per year instead of twice), or impose conditions — just because it can and because there is very little Europe can do about it. Compared to the united front and coherent political agenda China presents in its foreign policy in spite of its weaknesses, the EU looks rather inconsistent in its approach. It lacks a common strategy, political will and, inevitably, the instruments required to systematically pursue its interests in a bilateral relationship with China. The People’s Republic, a pragmatic and flexible actor, long ago learned from the U.S. how easy it is to deal with Europeans according to the old Roman principle of divide et impera. And indeed, China prefers bilateral contacts with important EU member states over dealing with the EU.

If you do not have awareness of your capabilities, the Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu said, your defeat in any war, or in more civilian terms, in any competition, is inevitable. If Europe wants to keep up with China’s ascension, Europe will have to make better use of its potential by turning it into real power and influence.

In his speech to the graduating cadets of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Obama asserted his country’s claim to global leadership quite forcefully: “America must always lead on the world stage. If we don’t, no one else will.” The book Paradox of American Power by political scientist Joseph Nye discusses the fact that the U.S. needs partners to be able to remain a leader — and these partners are welcome to show more self-confidence. Karl-Heinz Kamp is right when he states: “Even if in terms of power politics the European Union is a toothless tiger, it nevertheless has influence in regions where skepticism over Washington’s superpower attitudes is strong.” Europe can make good use of this influence in Asia to promote the integration of those values that still define the Western world into the world order, and to hold its ground in the region next to the U.S. and China.

Outlook

Some 20 years after its fortunate and peaceful reunification, Europe has “grown up” and has the capabilities to take care of its own security. A security threat that would require a massive U.S. presence is not on the horizon, not even the Ukraine-Russia crisis. And because of the commonalities mentioned before, the trans-Atlantic link is going to remain relevant in the future. Still, the partial withdrawal of the U.S. from Europe sends two messages. One of them reads mission accomplished: Europe has learned to stand on its own feet and to provide for its own security. And while there is a high degree of respect for Europe in the U.S., there is also the conviction that for the foreseeable future, Europe is not going to present any challenge to U.S. dominance at the global level.

The second message is: Europe will have to adapt to its new role. The words of admonition spoken by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates shortly before he left office still resonate: “The non-U.S. NATO members collectively spend more than $300 billion U.S. on defense annually which, if allocated wisely and strategically, could buy a significant amount of usable military capability. Instead, the results are significantly less than the sum of the parts.” Europe will have to work harder to forge a credible common security and defense policy and cannot always rely on the U.S. Europe will not be left alone at home, but becoming more self-reliant and carrying a larger share of the burden within NATO is for its own good. The litmus test will be its contribution to the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, set up as a result of the NATO summit in Wales.

In the future, Europe will have to demonstrate more unity and more coherence in its foreign policy. This also implies becoming a more independent actor and pursuing its own interests in relation to the U.S., as well as in relation to China.

This type of policy, however, has always been particularly difficult to adopt. In its Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) the EU still relies exclusively on intergovernmental coordination processes. But Europe is good at handling crises. Indeed, it has done little else since the end of World War II — always changing its mode of operation for the benefit of a stronger European community. The rise of China and the partial withdrawal of the U.S. serve as a wake-up call for Europe to lend more weight to its CFSP. The new global concert of powers puts Europe at a crossroads: Either accept the new geopolitical challenges and grow by continuing the integration process and becoming a smart power in a multipolar world, or turn into a relatively insignificant bunch of small- and medium-size states.

Comments are closed.