Europe’s shifting relationship with natural gas

By Dr. András Deák, John Lukacs Institute for Strategy and Politics at the Ludovika University of Public Service, and Dr. John Szabo, Institute of World Economics at the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies

From the very day that European leaders entertained the idea of importing Soviet natural gas in the 1960s, many criticized the decision — citing supply security and geopolitical concerns. Dependence on oil and natural gas exports from the Soviet Union and, subsequently, Russia, continued to be regarded as geopolitically precarious and insecure. As the eminent scholar Per Högselius writes in “Red Gas”: “Soviet natural gas, to a certain extent, did function, and was perceived of as an energy weapon and … it continues [to] do so in an age when the gas is no longer red.” The negative image of Russian natural gas persisted — especially as the geopolitical situation between the West and Russia deteriorated after the “color revolutions” in the post-Soviet space in the mid-2000s — but the share of Russian imports continued to grow.

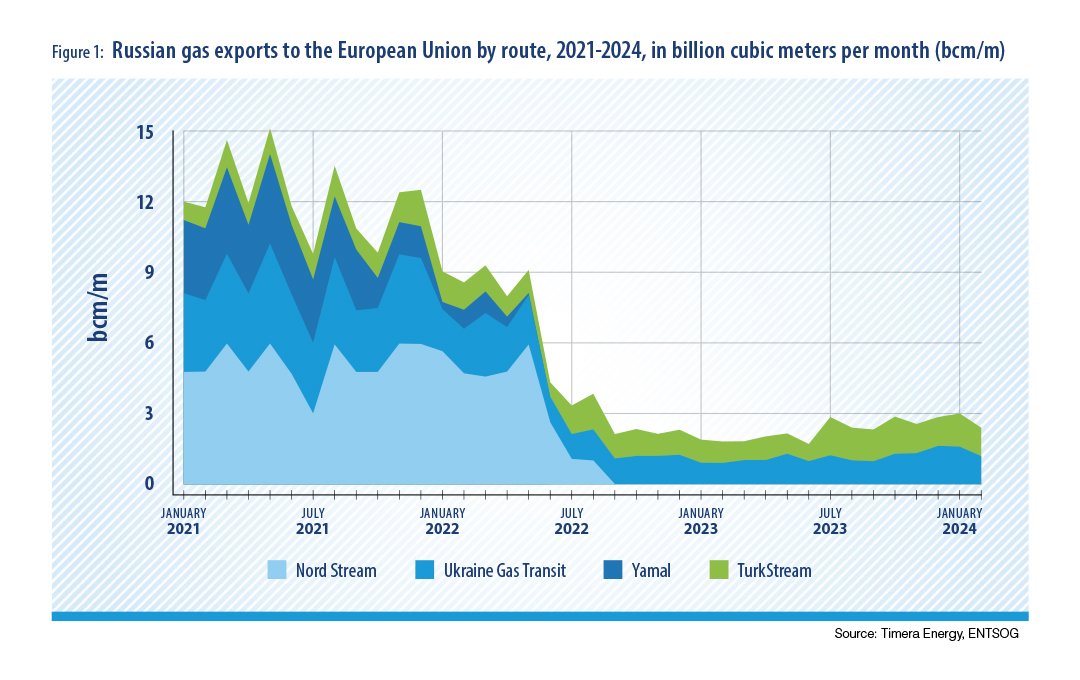

Russia’s majority state-owned energy giant Gazprom substantially decreased pipeline flows of natural gas to Europe when Russia again invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The company’s share of European Union gas imports decreased from more than 40% in 2021 to a mere 8% by 2023. Even if the Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports that have increased over the past two years are included, less than 15% of EU imports originate from Russia. Only a handful of nations in Central and Eastern Europe, namely Austria, Croatia, Hungary and Slovakia, have chosen to maintain pipeline imports — decisions based on a combination of geographical and political factors. Nevertheless, European natural gas markets have undergone “de-Russification,” inviting a reassessment of the future of natural gas in Europe.

Will it again become a secure source of energy in a post-2022 setting? Will the removal of security concerns regarding natural gas enhance the fuel’s prospects in Europe? As a point of departure, it is worthwhile to consider what one understands as energy security. For this, we turn to the Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre’s seminal 2007 paper “A Quest for Energy Security in the 21st Century,” which proposes four facets of energy security: availability, accessibility, acceptability and affordability. Availability considers whether deposits and/or production of the energy source are available. Accessibility looks at the geopolitical facet of energy security, including whether one can obtain the necessary access to the energy source. Acceptability narrows in on whether the given sociopolitical and environmental contexts make the consumption of the given energy resource permissible. Affordability looks at price and one’s ability to pay.

Natural gas is abundant globally, leading to a focus on its accessibility and acceptability, with some indication of its affordability. The shift in Russian natural gas exports is likely to be permanent and the new supply reality will generally be more advantageous from an accessibility point of view. However, the acceptability of natural gas is confined by climate policy.

The Accessibility of natural gas

The five-decade-long trend of Soviet/Russian natural gas exports to Europe came to an abrupt halt in 2022 when Gazprom slashed supplies to a fraction of previous levels (Figure 1). This prompted market restructuring that continues to date. The Kremlin clearly restricted supplies to exert strategic influence over European decision-makers, retaliate against Western sanctions, and inflict social and financial burdens on the target countries. This “gascraft” undermined Gazprom’s established corporate reputation, violated several legal obligations and agreements, and is incurring significant financial losses. However, its objectives remain ambiguous and their effect questionable.

The Kremlin’s actions prompted the collapse of Gazprom’s access to lucrative markets while barely influencing European foreign policy. EU member states were able to weather a heating crisis during the two ensuing winters as natural gas prices returned to prewar levels ranging from 25 to 30 euros per megawatt hour. Crucially, Moscow’s gascraft had little influence on Western decisions to assist Ukraine or to sanction Russian entities. If the Russian leadership aimed to secure wide-ranging political concessions through this course of action, their endeavor failed.

The failure of Russian strategy could prompt a gradual reassessment of priorities and thereby lead Moscow to prioritize business over politics. This course can be supported by Gazprom’s ambition to regain its market share and optimize the utilization of its idle Western Siberian capacities while fulfilling its tax obligations and generating profits for its shareholders. Concomitantly, it would also help the Kremlin regain political support by offering discounts to friendly European nations, in effect restarting the entanglement of politics and business as has been the case for decades in Eastern Europe.

As of April 2024, Gazprom was not restricted by any legal obstacles from increasing its shipments to the EU. The European Commission has proposed timelines for the complete cessation of Russian natural gas imports by the second half of the 2020s, but none of these have been adopted. Ironically, although Russian gas imports are not subject to EU sanctions, the possibilities for Russia to regain its market share are even dimmer than is the case with oil. It is illegal to buy Russian oil and petroleum products in the EU — apart from a few exceptions — even though the necessary infrastructure and supply chains are available and operational. However, if politicians opt to relax legal restrictions, Russia could resume oil exports in a reasonably short period.

Importing Russian natural gas into the EU remains legal. The lack of sufficient infrastructure for pipeline imports poses an obstacle to rapidly increasing flows. Out of the four primary transit routes that were operational before the war, Nord Stream was severely damaged, Yamal remains inactive and all flows on routes through Ukraine were ceased by Kyiv on January 1 when existing transit contracts expired. More than 200 billion cubic meters per annum (bcm/a) of existing and potential transit capacity has been compromised. Restoring these routes hinges on removing sector-specific sanctions and the emergence of European leaders who would lead an initiative to reconcile relations. Neither of these appear to be readily achievable.

With the closure of the Ukrainian route, Gazprom’s only remaining operable pipelines are those on the floor of the Black Sea, which have a combined capacity of 47.5 to 50.5 bcm/a. However, the subsea pipelines running through Turkish waters are at risk of being sanctioned by the West. These risks undermine Gazprom’s European export ambitions.

EU infrastructure capacity limitations restrict the reemergence of the prewar natural gas-market configuration. They prevent the resurgence of Russian natural gas, even in a crisis where global natural gas supplies are interrupted and Europe would need access to immediate supplies. Poland and Ukraine could dampen the shocks by reopening transits via the Yamal and Brotherhood pipelines, respectively, but their normative stance toward Russia would make it unlikely that they maintain these routes in the longer run, even if the war were concluded.

The restoration of pipeline infrastructure hinges on peace in Ukraine, the end of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s administration and looser technological sanctions. As time passes without significant increases in Russian deliveries, the European market is bound to consolidate while price levels and new contractual relationships stabilize. The lack of European incentives to relaunch Russian trade and the increasing complexity of Gazprom’s return are both consequences of this newly forming status quo.

Europe responded to the halt of Russian supply by reducing consumption and diversifying import sources. Eurostat reports that EU natural gas demand in 2023 was 17.6% lower than the average annual demand from 2017 to 2021. Mild winters, regulatory and voluntary demand reductions, fuel switching and offshoring natural gas-intensive industries supported the reduction, some of which may be reversed as prices decline. Europe substituted half of the Russian supply losses with LNG. The United States became the primary source of imports, as U.S. LNG’s share of the gas supply rose from 32.4% in 2021 to 69.1% in 2022, and further increased in 2023. This marks the reemergence of the U.S. as a key actor in Europe’s energy affairs. U.S. LNG producers respond to market signals as opposed to administratively set targets, as was the case with oil prior to the 1970s.

European buyers compete with their Asian counterparts for U.S. LNG cargoes that are priced according to market principles without any discounts provided on “strategic grounds.” Simply put, Europeans need to outbid competitors to secure access to the chilled fuel. The U.S. government has little influence over market prices and shipping destinations, unlike its ability to influence oil markets through regulation by the Railroad Commission of Texas during the first two-thirds of the 20th century.

Europe stands to benefit from importing LNG from the U.S. and other countries, as the depth of these markets increases the fuel’s accessibility. Since 2000, the global trade volume of LNG has grown nearly four-fold, far outpacing the growth of pipeline gas and allowing for the formation of an increasingly interconnected — albeit far from perfect — global market.

In 2021, the volume of global LNG trade exceeded European LNG imports by a factor of five, indicating the depth of those markets, and their expansion is far from over as export capacities are expected to grow throughout the 2020s. In the U.S. alone, authorities granted permission for an additional liquefaction capacity of 120 bcm/a to be constructed by companies through 2030. New capacities will be easily accessible to European buyers given their access to the Atlantic Basin, while reducing shipping risks associated with Middle Eastern sources.

Europe had to shift its natural gas import practices quickly and, in doing so, was forced to compromise. EU policymakers spent ample time and resources managing and “taming” a bilateral monopoly with Russia. They introduced policies that supported the unfettered, free trade of the resource by dismantling monopolies and long-term contracts, as well as eliminating take-or-pay and destination clauses. In a turn of events, European buyers’ quick pivot forced them to accept terms from U.S. and Middle Eastern sellers that resemble Gazprom’s from a decade or two ago. Offtakers, or buyers, made long-term commitments and agreed to pay a hefty premium to cover liquefaction, regasification, shipping, insurance and transit costs in addition to being subject to continuous market volatility. Previously, Europeans could rely on Gazprom’s contractual flexibilities and ability to balance markets, but that has ended and leaves buyers susceptible to the vagaries of global events.

The reconfigured terms of trade translate into improved accessibility as the geopolitical disposition favors European buyers, thereby underpinning security, but come with a decline in affordability. LNG simply tends to be more costly than was the case with abundant Russian natural gas provided by a seller looking to grow its market share. It has become clear that this is a price most of Europe can and is willing to pay, facilitating the irreversible formation of new trade patterns.

The objective of energy security policies is rapidly changing. Leaders’ ambitions to mitigate the geopolitical risks stemming from reliance on Russian flows were at the center of European actions for the past two decades. In Eastern European countries, such as Poland and the Baltic states, the issue was effectively the only item on the energy policy agenda. The abrupt pivot in trade renders the matter moot and reduces the relevance of the accessibility facet to energy security. In doing so, it raises other facets.

The acceptability of natural gas

When the Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC) published “A Quest for Energy Security in the 21st Century” in January 2007, there was rising awareness among state officials of the need to take climate action both within Europe and beyond. Nicholas Stern had just published his book “The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review” and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was finalizing its Fourth Assessment Report. Both underscored the dire implications of unmitigated greenhouse gas emissions, backing the EU’s decision to pilot its emission trading system and the European Commission’s initiative to emphasize climate action in the Barroso Commission’s 2020 Agenda.

Unsurprisingly, APERC also included “acceptability” into its conception of energy security, underscoring the need for energy sources that meet the “needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This concept drew on the United Nations’ “Our Common Future” report published in 1987, but was something that had yet to be integrated into mainstream policymaking in the field of energy. Although discussions on the matter proliferated at the time of APERC’s publication, its effect would be overshadowed by the economic crises and have little tangible effect until after the passing of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Energy security’s acceptability dimension has risen on the European policy agenda as social and political resistance to carbon dioxide-emitting fossil fuels increased over the past decade. Natural gas had been widely held to be a “clean,” “green” and even “sustainable” source of energy, and policy sought ways to enhance its accessibility. But the fuel eventually came into the crosshairs of EU policymakers as an unacceptable emitter as they began to focus on electrification and renewable energy with the Clean Energy for All Europeans Package published in 2016.

As if jolted from their enchantment with natural gas, policymakers began to question the environmental implications of the fuel’s continued consumption. Professors Kevin Anderson and Matthew Broderick underscored in a study for the EU that “fossil fuels, including natural gas, can have no substantial role in an EU 2°C energy system [EU strategy to achieve carbon neutrality and limit global temperature increases] beyond 2035,” which raised concerns over the lock-ins created by costly investment in natural gas infrastructure. Moreover, a long-standing concern related to natural gas also rose on the EU’s agenda: methane emissions.

The prime component of natural gas is methane, a potent greenhouse gas with a global-warming potential that is 28 times greater than that of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period and is 84 times more potent over 20 years. Thus, methane substantially accelerates climate change, even if its effects have been overlooked for years. The case of methane as a greenhouse gas is not nearly as straightforward as the unequivocal nexus between carbon dioxide and climate change because the Earth’s methane balance is much more complex. Methane is emitted and absorbed by sources ranging from human activities to bogs, marshes and wetlands, making it more difficult to discern the precise role that people play in its changing concentration. Nonetheless, it is clear that human activity is at the core of generally rising methane concentrations in the atmosphere.

The International Energy Agency indicated that methane concentrations are rising, and studies have shown that just less than two-thirds of this increase is linked to human activity, a third of which originates from the energy sector. Methane emissions are closely linked to fossil fuels, as the gas is abundant between coal seams, within oil fields and, quite obviously, throughout the natural gas supply chain, from where it is vented and leaks into the atmosphere. Natural gas may widely be understood as the least-polluting fossil fuel because of its low sulfur, nitrogen and particulate matter emissions compared with other fossil fuels, but life cycle methane emissions can increase its warming effect to match that of coal.

The dire climate impact of methane emissions makes it especially pertinent that regulators introduce a stringent framework on the measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) of emissions that can then form the basis of action targeting their reduction. An MRV system designed to curtail methane leaks is theoretically an easy decision, since it allows sellers of the resource to market and thereby profit from natural gas that would have otherwise dissipated. This is among the reasons that the European Commission introduced a methane strategy in 2018, which was followed with a regulation in May 2024. The acceptability of natural gas consumption hinges on the introduction of an MRV framework to convey that gas, while it has the lowest emission among fossil fuels, is not the low-emitting resource it has been systematically “greenwashed” to be.

The challenge with regulating the EU’s methane emissions is that they are largely external to the bloc. It imports piped natural gas from Algeria, Azerbaijan, Norway and Russia in addition to the numerous sources of liquefied natural gas ranging from Australia through Qatar to the U.S. Of its piped suppliers, only Norway has a credible framework forcing producers and infrastructure operators to measure and curb their methane emissions. In other cases, both with regard to piped natural gas and LNG, MRV standards are, at best, in the planning stage. The sovereignty of gas-producing countries raises a challenge, as states are reluctant to cede any sort of oversight control over what are frequently state-controlled assets. Officials are not willing to grant observers access to their treasured assets and, even if they were to allow some form of oversight, there is still a need to harmonize codes, guidelines and regulations. The issues are similar with LNG. However, the EU is not without tools.

The EU can, and has, used its market size to impose conditions on suppliers. After all, it leveraged its buying power to force the liberalization of markets that were formerly controlled by vertically integrated companies. More recently, the European Commission introduced joint purchasing via a self-developed platform to help buyers access natural gas for storage. This covered a fraction of total EU demand, but it began to leverage the size of the EU’s market by aggregating demand and instigating competition between sellers. The EU can grow this platform and use it to impose additional requirements on sellers, such as the MRV of methane emissions.

Beyond methane emissions, the carbon dioxide-emitting qualities of natural gas also undermine its acceptability in the energy mix. In principle, it can be consumed through 2035, but the EU would have to reduce the unabated volumes combusted to comply with targets set in the Paris Agreement. The EU no longer has the time to shift from coal to natural gas and then to renewables; it needs to quickly move toward renewable energy and cannot afford any unwanted lock-ins linked to natural gas assets. That said, it still needs to establish how it will substitute the fuel in the future.

Natural gas has a crucial role to play in meeting energy demand in difficult-to-electrify sectors, but its role needs to be limited to complementing renewable energy sources. Historically, natural gas was primarily consumed for industrial use, heating and balancing electricity generation. The energy transition has begun to alter its applications as the EU has substantially increased renewable energy production capacities and progressed with the electrification of its energy systems.

Natural gas will be less and less acceptable in electricity generation and increasingly costly to burn around the clock. Instead, grid operators will be forced to rely on gas turbines to balance the electricity network. The ability of these installations to quickly ramp up or decrease output makes them ideal to balance intermittent renewables. However, they will face rising competition from batteries, which are increasingly inexpensive while offering the option to store renewable electricity and dispatch it instantaneously.

Substituting for natural gas in heating — especially for industry — is set to take much longer than the pace at which it is phased out of electricity generation. In heating, its prime alternative is the heat pump, which offers a potentially renewable electricity-based mode of efficient heat production. The difficulty in this case is the vastness of the endeavor, as every household with a natural gas boiler must convert to this (or another) new low-carbon technology. Heat pump diffusion has grown in recent years, responding to high natural gas prices, generous government subsidies and government decisions to restrict natural gas boilers in new construction, but its uptake is from a low base and many households are reluctant to take on this technological change.

Substitution in the industry sector is among the most difficult and costly. The role of gas in producing high temperatures and as a feedstock in a host of processes, ranging from steel to fertilizer production, makes it a seemingly indispensable component of modern production. Electrification is not always palatable, leading experts to suggest the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and/or shifting to hydrogen as possible alternatives.

The long-term acceptability of natural gas usage is thus predicated on its decarbonization. Pairing natural gas combustion with CCS introduces a few issues, most prominent of which is the need to deploy the technology at scale. Very few CCS facilities are currently operational globally and, while their numbers have been growing, it is far from the pace necessary to support its widespread adoption. The EU has been frustrated with its slow rollout, but most integrated climate and modeling exercises indicate that it will be essential to keeping global warming below 2 degrees Celsius compared with preindustrial levels.

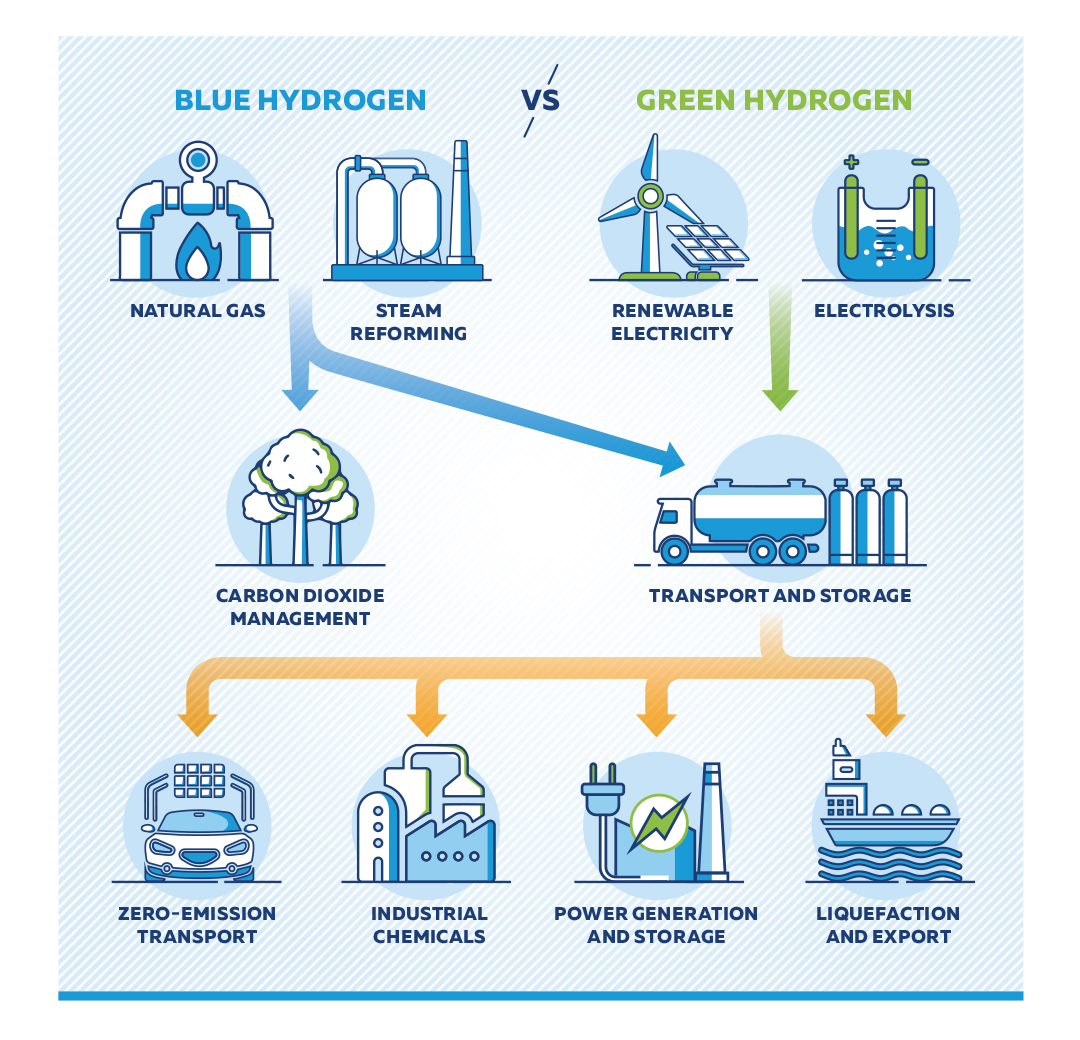

An alternative is to adopt hydrogen — a decarbonized form of natural gas — for a long-term role in the energy mix. The first element of the periodic table is already widely produced from natural gas and consumed as industrial feedstock in oil refining as well as fertilizer and methanol production. Hydrogen is produced by reforming natural gas through a steam-methane process. Pairing it with CCS could provide a low-carbon feedstock and potential nonemitting source of energy that extends the legitimacy of natural gas’s continued use in European industry. Norwegian energy company Equinor, among the largest actors in this field, is developing projects in the North Sea. But here, too, the success of fossil hydrogen’s uptake hinges on scaling CCS. An alternative technology may be methane pyrolysis — splitting the carbon from the hydrogen atoms without combusting the former — but this remains in an even more rudimentary phase of development.

Conclusion

The EU has been able to resolve many of its natural gas-linked energy security problems despite the shock of the energy crisis and Russia’s decision to cut off natural gas supplies to most of Europe. It substituted for Russian gas imports with LNG from various suppliers. Mediated by the market and largely sourced from the U.S., this offered a geopolitically tenable solution to the EU’s gas supply woes, as it could rely on an ally despite having to pay higher market prices. As the geopolitics and price of this energy source stabilize, the questions related to its security are changing.

The EU’s climate agenda has been extremely slow to develop, with tangible effects on the energy system materializing over decades. However, it has now turned into an immense force that inhibits the unabated consumption of fossil fuels. Natural gas has long been seen as the transition fuel that would continue to play a substantial role in the bloc’s energy mix for years, but for this to continue it needs to become more climate compatible. Reducing methane emissions is essential to allow for its use in an acceptable manner. Otherwise, the burning of natural gas contributes to exacerbating climate change and undermines the credibility of the EU’s climate-mitigation ambitions. Development of a credible plan to decarbonize natural gas consumption is a long-term necessity that depends on the ability of companies to develop either CCS or alternative technologies. The EU may have overcome the resource, geopolitical and market constraints of natural gas, but its unfettered consumption is undermined by the environmental implications of its combustion.

Comments are closed.