A Western response to Russia’s hybrid threat

By Capt. David P. Canaday, U.S. Army

Hybrid war is a term that is sweeping the strategic security community worldwide. Much like the torture technique noted in this article’s title, hybrid war has the ability to bleed its target through myriad attacks conducted below the perceived threshold of conflict. Assorted, seemingly inconsequential actions, when combined, can plunge an otherwise functioning nation into chaos. To many NATO nations living in Russia’s shadow, the implications of this threat are deeply troubling.

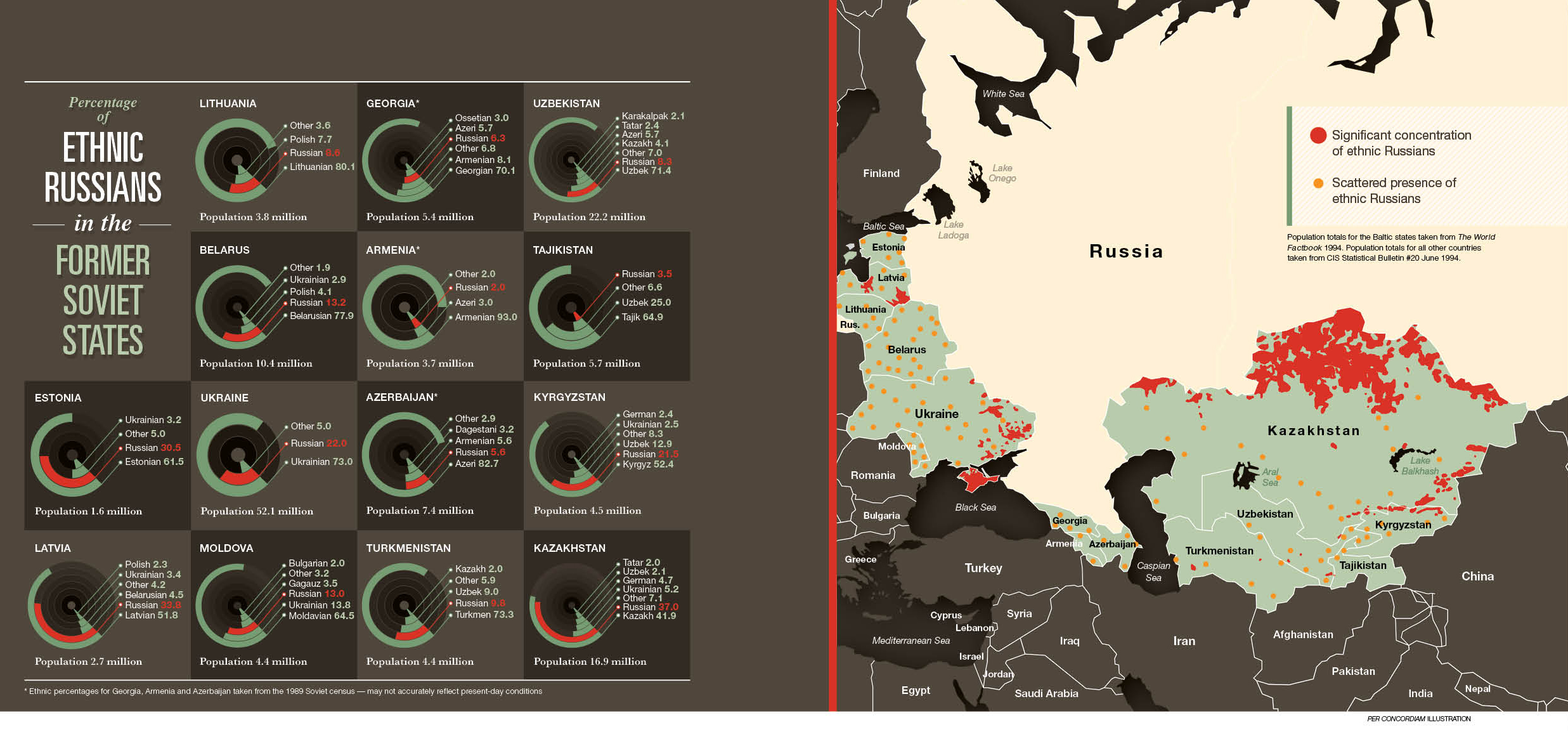

As Russia’s forceful intervention in Ukraine grinds on, the question that all other former Soviet countries in Russia’s “near abroad” and NATO must answer is: “What are effective responses to Russia’s version of hybrid warfare?” An examination of the aspects that have made it successful provides insight into deterrence and allows us to apply different techniques to disrupt future Russian hybrid threats. Analyzing how these tactics are deployed in neighboring countries to exploit seams between these governments and their ethnic Russian citizens — using Latvia as a case study — gives us a reference point to discuss how to respond.

Defining Hybrid War

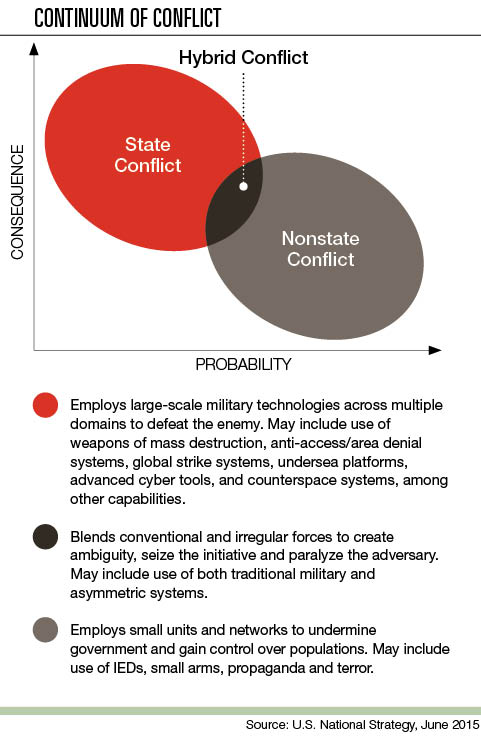

The term hybrid warfare is often misused, so our first task is to define it. Fortunately, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has already done this in the latest U.S. National Military Strategy (NMS). The NMS describes hybrid warfare as the following:

“… warfare that blends conventional and unconventional forces to create ambiguity, seize the initiative and paralyze the adversary. Hybrid war may include use of both traditional military systems and asymmetric systems. … Such conflicts may consist of military forces assuming a non-state identity.”

Hybrid war is an ambiguous concept and cannot be narrowly defined. The DOD understands hybrid war as a point on a linear progression of consequence and probability.

The Potomac Institute, which completed an analysis of Russian hybrid war in Ukraine, also addresses the subject and effectively describes the term using common language. Like the NMS, it characterizes hybrid war as a steadily increasing function of intensity and state responsibility. The Potomac Institute defines hybrid war as “incorporating a range of different modes of warfare, including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder.” Janis Berzins of the Latvian National Defense College’s Security and Strategic Research Center likens it to mafia activity — something that exploits a country’s weaknesses.

Gen. Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of the Russian Armed Forces, wrote in Russia’s Military-Industrial Courier that hybrid warfare consists of six stages that use military, economic and diplomatic mechanisms to pressure a nation or group to elicit desired reactions and responses.

Gen. Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of the Russian Armed Forces, wrote in Russia’s Military-Industrial Courier that hybrid warfare consists of six stages that use military, economic and diplomatic mechanisms to pressure a nation or group to elicit desired reactions and responses.

- Stage 1 is “hidden emergence,” when differences of opinion or policy conflicts begin to emerge.

- Stage 2 is “aggravation,” when these differences transform into contradictions that are noticed by political and military leadership.

- Stage 3 is the “beginning of conflict,” which features the deepening of contradictions and the start of open strategic deployment of military means.

- Stage 4 is “crisis,” which consists of crisis reactions and a full range of actions (note that the ratio of military to nonmilitary actions is still only 4:1).

- Stage 5 transitions to “resolution” and features isolating and neutralizing military conflict. It is in this phase that leadership shifts to a more political and diplomatic relationship and when the search for conflict regulation begins.

- Stage 6 is the “establishment of peace” and post-conflict operations. At this point, gains from the action are consolidated, and the main goal segues into lowering tensions between the two countries.

Gerasimov’s depiction of hybrid war is notable for several reasons. First, it identifies the start of conflict at the point when two states have a difference of interests, a much lower threshold than Western definitions. Second, it abandons the linear concept of hybrid war for more of a parabolic progression. In other words, military and nonmilitary operations reach a critical tipping point, then begin to decline in severity and repetition as the strategic goals of the hybrid operations are accomplished. This difference in understanding is apparent as we examine the significant center of gravity that ethnic Russians represent within every neighboring country, and those nations’ often lackluster efforts in addressing this phenomenon.

As every small-unit leader knows, the most vulnerable place in any defensive position is at the “seams” between subordinate units. Russia chooses to launch its hybrid attacks along seams that exist within a targeted government or country. These actions are usually successful because the more technical the coordination required to respond, the more likely the response will arrive too late to be effective. Russian strategy capitalizes on seams in a country’s defense, such as the seam between ethnic Russians and the governments of the states in which they live. By applying pressure along these seams, Russia is able to enact a kind of reflexive control described by Berzins as “making your opponent do what you want without the opponent realizing it.”

citizenship and propaganda

To realize the advantage offered by a seam between these ethnic Russians and their governments, one need look no further than Russia’s military doctrine, which states that the use of Russian military force is justified to “ensure the protection of its citizens located beyond the borders of the Russian Federation.” Russia used this doctrine as an excuse to conduct military operations in Georgia and Ukraine, while destroying significant portions of those countries’ militaries and embroiling them in unresolved border conflicts that hinder attaining NATO or European Union membership.

In both Georgia and Ukraine, Russia’s hybrid war began by exploiting seams created by breakaway ethnic groups. Breakaway republics in Georgia and ethnic Russians in Ukraine felt isolated by their countries’ policies. For example, a June 2014 Russia Today poll showed that a significant percent of the Crimean population felt that life would be better in the Russian Federation. Also, eastern Ukraine and western Ukraine were polar opposites in their opinions of the EU, Russia and NATO, as indicated by a March 2014 Gallup poll. Such disconnect left ethnic Russian Ukrainians feeling isolated.

Russia offered a respite from such feelings by providing Russian passports that entitle the bearer to the benefits of Russian citizenship. As Vincent Artman noted in his article “Annexation by Passport,” by making Russian passports available to all who asked, Russia was able to create a significant enclave of Russian citizens inside the Abkhaz and South Ossetian regions of Georgia. In the case of Abkhazia, about 80 percent of citizens received Russian passports, according to then-Abkhaz Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Shamba. This provided ample justification, from the Russian perspective, for military intervention when Georgia attacked the breakaway republics in response to escalated provocations. Artman notes that Russia also handed out thousands of passports in Crimea and eastern Ukraine and, by doing so, not only contested Ukraine’s sovereignty, but also set the conditions for annexation.

In both cases, Russia painted a positive impression of what life would be like under the Russian Federation compared to Georgia or Ukraine. This juxtaposition, along with an increased desire by both Georgia and Ukraine to pursue NATO and EU membership, did nothing but fuel anti-state sentiments in these regions and increase the desire of ethnic Russians to join the Russian Federation. Once that stage was set, the fate of Crimea and Georgia’s breakaway republics was the same — swift Russian military intervention and annexation as soon as the seam between people and government had been fully exploited.

Russia’s use of this strategy places any state with a population of ethnic Russians at risk of Russian meddling. Of all the former Soviet Republics, none has been more concerned with Russia’s new hybrid war strategy than the Baltic states. Of those, Latvia has the highest concentrations of ethnic Russians.

A Latvian case study

According to The World Factbook, ethnic Russians account for 26 percent of Latvia’s population, which leads to complicated politics between the state and local governments and the ethnic Russian minority. Often, city mayors and other local leaders, representing the interests of ethnic Russians, act contrary to the policies of the Latvian president and government leadership. Igors Vatolins, leader of the Movement of European Russians in Latvia, a group that aims to unite pro-European Russians, noted in an interview that Latvia is the weakest link in NATO’s chain because of its pro-Putin contingent of ethnic Russians. Of the 575,195 Russians listed in the latest Latvian population census, only 356,482 are Latvian citizens, which leaves 172,372 noncitizens (30 percent) and 46,228 people in “transition” (8 percent), all remaining without the right to vote or serve in the military. This led Andrew Higgins to note in The New York Times that some Russian analysts are suggesting that such ethnic Russians could provide the leverage needed to force the revision of borders in places like the Baltic states.

All these factors combine to create an uneasy and sometimes hostile relationship between Russia and other former Soviet republics. According to Mike Collier of BNE IntelliNews, Russian-language media dominates the landscape, broadcasting information in Russian all day, compared to the hours broadcast by their Latvian counterparts. And IHS Janes Defense Weekly observes that Russia spends over $300 million annually on state-run news agency Russia Today, greatly outpacing its competitors. Since Latvian news agencies cannot compete with Russia’s massive broadcasting budget, its Russian population remains psychologically isolated from the country it lives in. This divide can lead to ethnic tensions and potential isolation. Given the proper catalyst, civil unrest on a large scale could result.

The Latgale region of Latvia hosts a large cohort of ethnic Russians and Latgalians — separate ethnic groups with their own languages — and is the logical location for any Russian intervention. The Latgale region remains loyal to Latvia. Despite Russian efforts to exacerbate differences between the Latgalians and Latvia, the majority believe that the benefits of living as noncitizens in European Latvia far outweigh living as Russians under Russian authority. Therefore, the immediate threat of Russian intervention could be considered low to medium.

The Latgale region of Latvia hosts a large cohort of ethnic Russians and Latgalians — separate ethnic groups with their own languages — and is the logical location for any Russian intervention. The Latgale region remains loyal to Latvia. Despite Russian efforts to exacerbate differences between the Latgalians and Latvia, the majority believe that the benefits of living as noncitizens in European Latvia far outweigh living as Russians under Russian authority. Therefore, the immediate threat of Russian intervention could be considered low to medium.

However, as long as this population remains isolated and relegated to noncitizen status, the potential for Russian intervention will remain. In August 2015, BNE IntelliNews noted that unemployment in the Latgale region of Latvia remained the highest in the country at 18.4 percent, even as the rest of the country dropped to 8.5 percent. This kind of disparity in opportunity means that until citizenship and economic issues can be resolved, or at the very least improved, the door to Latvia remains wide open to Russian influence.

Strategic communication resources

One technique that can be used to head off a potential hybrid war scenario in Latvia is to offer a convincing counternarrative to that being peddled by Russian news media. One resource is the NATO Strategic Communications Center of Excellence (StratCom COE) in Riga. A newly founded NATO center of excellence, StratCom COE is establishing itself in NATO as the subject matter expert on strategic communications and is seeking proposals from NATO members on how best to utilize the center, via training or advising.

As of March 2015, the main focus of the StratCom COE was combatting use of social media by the Islamic State. But in January 2016, a new paper on Internet trolling as a hybrid tool in Latvia was published, the first publication that deals specifically with Latvia. While this constitutes progress, much more needs to be done. Since my time in Latvia in 2015, the center has not shown much enthusiasm for pursuing a program to counter Russian disinformation in the Baltic countries, nor for providing suggestions for effective information operations in the Latgale area. If Baltic States want to produce more ideas for countering Russian propaganda, they need to be more vocal in requesting use of the StratCom COE for that purpose. Only then can they leverage the intellectual power at this center for messaging ideas and goals.

The EU has a similar resource, East StratCom Team, which is working toward countering the Russian information campaign and is helping highlight and disprove much Russian propaganda. It produces a weekly breakdown of all the disinformation directed at European audiences. This resource is a good start and should be expanded to actively counter the Russian propaganda machine.

Reform efforts

The best way to thwart potential hybrid war threats is to connect ethnic Russians to their countries of residence. Latvia’s citizenship requirements are strict. Those desiring citizenship must pass tests on the Latvian language, history and constitution. Some view these requirements as discriminatory against ethnic Russians who do not speak Latvian. While such nationalism on the part of Latvia is certainly understandable, given its historic relationship with Russia, in this case, it is doing Latvia more harm than good by isolating ethnic Russians. Regardless of the true difficulty of these tests, perception of discrimination and isolation is all the Russian Federation needs to conduct effective and convincing information operations.

Recently, Latvia has made positive changes in its citizenship laws; noncitizens who have a child in Latvia can now elect for their children to receive Latvian citizenship, according to Saema News. More than 90 percent of ethnic Russian parents in Latvia are now choosing citizenship for their children. This act, and the large-scale response to it, is significant as ethnic Russians, who could have remained isolated from the Latvian government, become more invested in a Latvia that is independent of Russian intervention.

![Pro-Russian activists wave flags of the Russian-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine during a gathering of Latvia’s large ethnic Russian minority in Riga, marking an anniversary of the end of World War II. [AFP/GETTY IMAGES]](https://perconcordiam.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/GettyImages-488923001.jpg)

The recent European Reassurance Initiative has created the conditions to identify areas where improvements can be made. Each Security Cooperation Office has the ability to identify Humanitarian Civic Assistance programs that will complement existing U.S. DOD and State Department missions inside a country. These projects can be anything that serves the basic economic and social needs of the people. They can even involve host nation military and paramilitary elements to enhance relationships in the region, provided they are not paid directly to these groups. Such actions, while a monetary investment in the short-term, will be more effective in stopping Russian anti-Latvian narratives than the cleverest messaging or the hardest-hitting sound bites.

Conclusion

When the Russian Federation applies hybrid warfare in its near abroad to create wedges between a state and its people, the Russian diaspora in these countries becomes a source of potential tension. It is a continual pressure point that can be easily targeted and exploited by Russian propaganda. Even if the worst case scenario — a Russian invasion — does not happen, the potential for meddling is a constant. Ethnic Russian populations will always be seen as pawns by Russian military strategists because they provide not only a justification for Russian action, but also in many cases a fifth column of support for Russian policies and agendas.

As Russia enjoys success and learns from setbacks while implementing hybrid warfare strategies, it will use similar tactics to control its near abroad. The best defense for Russia’s neighbors must be more than simply reacting to Russian propaganda and accusations; it must be to proactively target the needs of the ethnic Russian’s who are often isolated from their governments. Integrating ethnic Russians is a problem that all states with significant Russian populations will have to solve before they can move past the threat of Russian intervention and on to a more peaceful and productive future.

Comments are closed.