Establishing a strong national identity and assimilating immigrants are critical to fight terrorism

By Capt. Lars Scraeyen

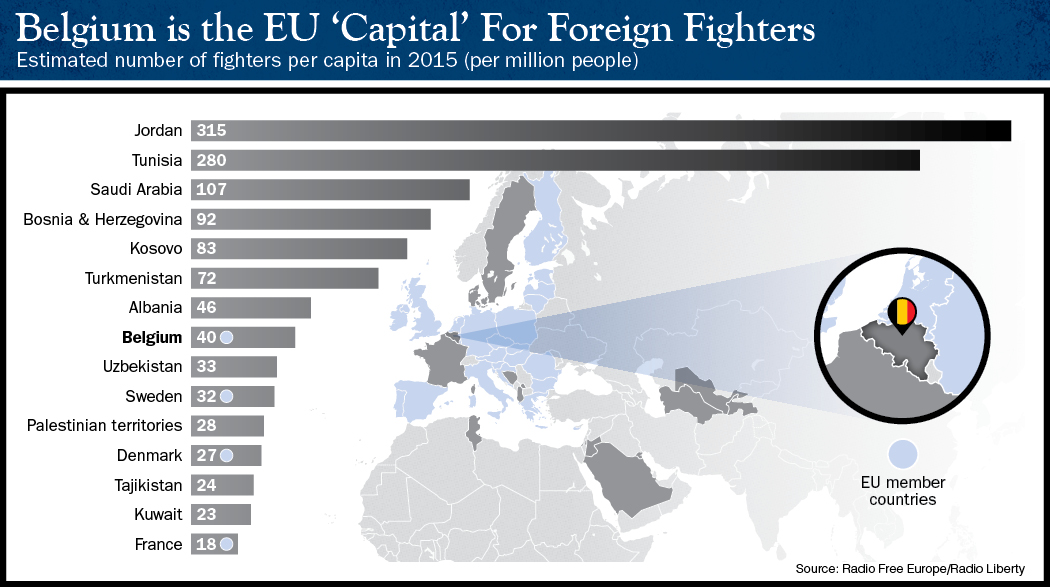

With a population of over 11 million, Belgium stands out among other Western European countries as a source of foreign terrorist fighters (FTF) in Syria and Iraq. As of July 2016, 457 FTF were believed to be from Belgium. While this represents only about a third of France’s number of FTF, Belgium’s per capita share is more than double. Concerned over these disproportionate figures and the involvement of a number of returning Belgian FTF in foiled and successful terrorist attacks — but also due to pressure from heavy international media attention — the Belgian government has, since 2015, intensified its efforts to understand and prevent radicalization. While many different tools are being explored and developed in this field, we shall look at the development of a Belgian counternarrative.

As explained by Henry Tuck and Tanya Silverman in The Counter-Narrative Handbook, published by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, counternarrative is a catchall term for a large group of activities ranging from campaigns led by grassroots civil-society, youth or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to government strategic communications. They define a counternarrative as “a message that offers a positive alternative to extremist propaganda, or alternatively aims to deconstruct or delegitimize extremist narratives.” A narrative is defined in its simplest terms by Dina Al Raffie in a 2012 article in the Journal of Terrorism Research as “a coherent system of interrelated and sequentially organized stories.” As she points out, these stories are so deeply ingrained in cultures that they are an essential part of people’s identities and their place within any given cultural setting. Al Raffie also noted that studies on radicalization proved that identity is at the forefront of the radicalization process and that their degree of success lies in the radical’s ability to provide the radical-to-be with a distinctive identity.

Considering that a counternarrative contains a narrative, and that narratives in turn are an essential part of someone’s identity, we will focus on this to discuss the challenges and opportunities for Belgium in developing an identity-based narrative as part of the counternarrative. Is there a relationship between a Belgian national identity and a sense of belonging that might help us understand why the country has produced so many FTF per capita? What might this mean for the development of a counternarrative in Belgium?

Considering that a counternarrative contains a narrative, and that narratives in turn are an essential part of someone’s identity, we will focus on this to discuss the challenges and opportunities for Belgium in developing an identity-based narrative as part of the counternarrative. Is there a relationship between a Belgian national identity and a sense of belonging that might help us understand why the country has produced so many FTF per capita? What might this mean for the development of a counternarrative in Belgium?

Societal security and identities

To guide us through this discussion, we will refer to the Copenhagen School’s securitization theory and the notion of societal security, centered on the sustainability and evolution of traditional patterns of language, culture, and religious and national identity and custom. Within this framework, the importance of speech acts, or what we refer to today as a narrative, was already recognized. The securitization theory was a key development in theorizing about security and dates back to the publication of Barry Buzan’s book People, States and Fear in 1983. The theory continued to evolve, and the Copenhagen School became a label for a collective research agenda from various academics at the Copenhagen Peace Research Institute in Denmark. Their work culminated in 1998 with the publication of Security: A New Framework for Analysis. This work developed in the post-Cold War period within a context that called for the broadening of security to include issues that had been neglected.

Security, as claimed by the Copenhagen School, was not just about states, but related to all human communities; nor could it be confined to an “inherently inadequate” focus on military force. Buzan’s approach argued that the security of human communities — not just states — was affected by factors in five major sectors, each of which had its own focal point and method of prioritizing:

- Military security: concerned with the interplay between the armed offensive and defensive capabilities of states and states’ perceptions of each other’s intentions.

- Political security: focused on the organizational stability of states, systems of government and the ideologies that give them their legitimacy.

- Economic security: revolved around access to the resources, finance and markets necessary to sustain acceptable levels of welfare and state power.

- Societal security: centered on the sustainability and evolution of traditional patterns of language, culture, and religious and national identity and custom.

- Environmental security: concerned with maintenance of the local and the planetary biosphere as the essential support system on which all other human enterprises depend.

A common claim among jihadis is that Muslims’ societal security (to use the above framework) is threatened. Terrorists often rely on discursively created threat perceptions, through their speech acts or narrative, claiming that the Muslim community worldwide is being threatened by “the West.” For instance, in his 1996 declaration of war against what he called the American occupation of “the land of the two holy places,” Osama bin Laden called for the entire Muslim community to take part in the fight against the enemy.

States, as well as terrorist groups, tend to act in terms of aggregate security, or as Buzan described it, allowing their activities in one security sector to color another. In this sense, the current discussion on narratives and counternarratives is the result of transnational terrorist threats to both our political (the ideological foundation and legitimacy of the state) and societal security (culture, customs, identity). For this article, we will focus on the societal security sector, centered on identity.

Buzan relied on a two-stage process to explain how and when an issue is to be perceived and acted upon as an existential threat to security. The first stage concerns the portrayal, part of a narrative, of certain issues, persons or entities as existential threats to referent objects. The Copenhagen School argued in favor of seeing security as a discourse through which identities and threats are constituted rather than as an objective, material condition. This securitization move can be initiated by states, but also by nonstate actors such as trade unions, popular movements or extremist groups. The use of a language of security does not imply that the concern is automatically transformed into a security question. The consensual establishment of the threat needs to be sufficiently salient to produce substantial political effects.

Key to the securitization move is the notion of “speech act.” Speech acts are conceived as forms of representation that do not simply depict a preference or view of an external reality but also have a performative effect — much like the narrative we are studying. To a certain extent, the issue of the development of narratives and counternarratives is far from new, but there is now an unprecedented number of different media through which the “speech acts” are performed, many of which governments have no control over.

in March 2016. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The second stage, crucial to the securitization process, can only be completed when the securitizing actor has convinced its audience (public opinion, politicians, communities or potential jihadis) that a referent object is existentially threatened. The Copenhagen School considers the speech act — the discursive representation of a certain issue as an existential threat to security — the starting point of the securitization process, because an issue can become a security question through the speech act alone, regardless of whether the issue genuinely represents an existential threat materially.

Buzan emphasized, however, that a discourse that takes the form of presenting something as an existential threat to a referent object — for instance Islam or the umma — does not by itself create securitization, but only represents a securitization move. The issue is only securitized when the audience accepts it as such. Insights from Buzan as well as Lene Hansen’s 2013 book The Evolution of International Security Studies indicate that security is seen as a discourse through which identities and threats are constituted; “terrorism” and “terrorists” were actually not seen as threats, actions or actors that could be objectively identified, but just as signs that constituted a “radical Other.” The anti-American/Western and anti-globalization rhetoric of jihadist opinion leaders and strategists is perceived as threatening to the Western identity (or societal security), which unavoidably results in us paying attention to it. Threats to identity are always a question of the construction of something as threatening to a collective “we.” This threat also has the effect of strengthening the construction of this collective “we,” as Buzan claimed. The “we” in this case is the West, the globalized or even the non-Muslims, in contrast to the automatically created “Other”: the nonglobalized or Muslims.

Stuart Croft, in his 2012 book on securitizing Islam, points out that, at this point, an individual and his attitude toward security transforms through a securitization move affecting both the lives of one group and the “Other.” This may lead to the construction within a society of an in-group and an out-group. Croft specifically referred to the way the Muslim identity was caught up in a securitization move in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and the London Metro bombings in July 2005, when Britain was directly confronted with jihadi terrorism. Jihadi terrorism, and specifically al-Qaida at its roots, was a concept that gave way to many misconceptions about Islam, Islamism and jihad, in turn leading to more radicalization within the Muslim community based on the development of enemy images.

Within a discussion of surveillance systems in the European Union, Thomas Mathiesen discussed the notion of enemy images in his 2013 book Towards A Surveillant Society. He wrote that it was not only images of Muslims that developed among politicians, in the media and among the citizens of Europe, but also images of terrorism, organized crime and of foreign cultures with various Muslim populations up front. These images, he continued, are not pure fiction. Terrorism and organized crime and the increasing number of foreigners on the EU’s doorstep are actually real problems. But around these realities were developed images that constituted serious exaggerations of dangers.

Many security measures have been adopted by governments in response to perceived threats posed to societal security. One of the common threats to national identities is immigration, and by consequence, immigration policy, is probably one of, if not the most, securitized issue in many European countries, especially since the increased refugee flow in 2014. In this respect, according to Croft, it is useful to look at immigration and population figures of Muslims — considered to be the “radical Others” within this discussion on radicalization. In Europe as a whole, the proportion of the Muslim population is even expected to grow by nearly one-third over the next 14 years, rising from approximately 6 percent of the region’s inhabitants today to 8 percent in 2030, the Pew Research Center reported in 2011. Furthermore, “Muslims are even projected to make up more than 10% of the total population in 10 European countries: Kosovo (93.5 percent), Albania (83.2 percent), Bosnia and Herzegovina (42.7 percent), Republic of Macedonia (40.3 percent), Montenegro (21.5 percent), Bulgaria (15.7 percent), Russia (14.4 percent), Georgia (11.5 percent), France (10.3 percent) and Belgium (10.2 percent),” according to the Pew report.

These figures for Belgium might be surprising, but as Milica Petrovic rightly pointed out in a 2012 article for the Migration Policy Institute, Belgium has often been overlooked as a country with a long history of immigration. Since the end of World War II, and especially since the 1960s, Belgium has possessed a large immigrant workforce. Brussels signed a number of labor migration agreements with several countries from Southern Europe (mainly Italy), North Africa (mainly Morocco) and Turkey. These agreements included lenient family reunification rules. From 1974, labor migration was limited by the government, but the reunification of families continued. Over time, migration rules continued to harden. This past has given Belgium a large second- and third-generation Muslim community.

As indicated by Dina Al Raffie, in a 2013 article in the Journal of Strategic Security, it has been suggested that these second- and third-generation Muslims face difficulties in balancing religious and national identities for two reasons. On the one hand, unlike their first generation predecessors who follow a more traditional Islam, second- and third-generation immigrants are found to have a more intellectual approach to their religion. The individualization of religious identity creation might also, because of conflicting views within the family, lead to disconnection and alienation from family. On the other hand, socio-economic, structural factors such as unemployment and low social standing might produce a sense of disaffection with the host country, preventing them from fully identifying themselves as a national. In this situation, the individual searches for another identity.

Belgian identity, unity and belonging

Throughout the existence of Belgium, societal security — particularly the linguistic and cultural dimension — has played a prominent role in the political debate. It has resulted in a political structure with six different governments: one federal, three regional (Brussels Capital, Flanders and Walloon regions) and two community governments (the French linguistic community and the German linguistic community). The Flanders region and Dutch-speaking community governments merged over time. The fault lines driving these reforms within Belgium remain important to this day and have led, gradually since the 1970s, to greater autonomy for the different regions and communities. At this point, the federal government remains largely responsible for internal affairs and security, immigration, justice, foreign affairs and defense. Culture, education, health care, unemployment and foreign trade are powers handed completely, or to a large extent, to the regions or communities.

A study by the Walloon Institute of Assessment, Forecasting and Statistics from 2014 on Belgian citizens’ identity showed that over the past 10 years, the number of Walloon citizens who feel they are different from Flemish citizens almost doubled, from 35 percent to 65 percent. Nonetheless, almost 8 out of 10 still consider themselves Belgians. A Catholic University of Leuven (Flemish) poll revealed that only 67 percent of the Flemings consider themselves to be Belgians. The ongoing political and public debate on continuing state reforms and the call for greater autonomy hasn’t gone unnoticed in the many migrant communities. Muslim migrants might wonder, for instance, why they should adopt a national identity and adapt to Belgian national values if the regional and cultural identities and values of the subregions seem to weigh heavier than national identity.

While discussing the securitization of Islam in the United Kingdom, Croft studied the impact of the 9/11 attacks on the lives and perceptions of individuals in relation to their different identities and Islam. As with the Belgian example, he also noted that regional identities (English, Scottish or Welsh) were deemed to be of higher importance than an overarching British identity. In September 2007, the British developed a new national motto in reaction to growing nationalism in Wales, Scotland and England and disenchanted ethnic minorities who were damaging the seams of British unity. For a number of reasons, the British identity had been under fire, but the terrorist threat invigorated the debates about identity and the model for minority integration. It was said that the time had come to build bridges instead of walls between the different races and cultures in Great Britain. Lord Taylor of Warwick, cited in Croft’s book, considered it vital for people from different communities to feel included in the British identity, alongside their other cultural identity. The situation at that time in Britain — the struggle with different identity issues while addressing immigration and radicalization — is strongly analogous to the Belgian situation.

Although the Belgian federal and regional governments were aware of worsening radicalization, the rising number of Belgian foreign fighters, and the growing domestic terrorist threat since 2012, no significant extra measures were adopted until after the Charlie Hebdo attacks in France in January 2015. Why did Belgium hesitate to respond following the attack on the Jewish Museum in Brussels in May 2014? Did it take an attack in a neighboring country and an antiterrorism police action that turned into a shoot-out to persuade authorities to introduce measures to fight terrorism?

Belgium waited for the momentum created by the attacks in France because, even though the threat was apparent in May 2014, the attack in Brussels fell at the worst possible time for Belgium to unite against terrorism. It was a month of strong political division in Belgium fostered by vivid debates in the media and aggressive political campaigning. The attack took place only one day before the combined regional, national and European elections were held. National unity in the face of terror was something that just wasn’t feasible then, especially with a rising regional nationalist party calling for more independence.

All political parties agreed to refrain from using the attack in their final effort to influence the electorate. The attack was dealt with in an atmosphere of serenity without being openly politicized, contrary to what has been happening in Belgium since the attacks in France in January 2015. The May 2014 attack was insufficient to unite Belgium in the face of terrorism and reinforce the Belgian identity, as happened in other countries such as France. Nevertheless, the attack took on significant importance when the electorate chose a new government a day later. In the wake of the attack, people were concerned about their security and the limits of a multicultural society. The election outcome and the governmental agreement of the newly elected government were clearly influenced by the attack, multicultural problems and the need for enhanced security.

The commitment to respond to the threat from extremism and radicalization had never been so present in declarations from previous governments. But some of the proposed measures in the new agreement went well beyond the federal government’s authority. Even though the May 2014 momentum was only partly exploited, it paved the way for a new direction in counterterrorism policy, though the public needed an incentive to accept the proposals. That incentive arrived in January 2015. Only days after the attacks in France, the government announced efforts to implement the governmental agreement. The combination of the attacks in France and the antiterrorist police action in Verviers delivered the momentum the government needed. Unity, however, was still lacking. Almost immediately after the government announced 12 counterterrorism measures, some coalition members expressed concerns about them.

Most of the measures can only be viewed as repressive. This focus of the federal government shouldn’t come as a surprise. Since the 1970s, Belgium has undergone a series of state reforms and constitutional adjustments, decentralizing power to its autonomous regions and communities. Many powers were passed to the regional governments. The rapid evolution of the security environment after the end of the Cold War, neglected by state reforms, has left the federal government with only a half-filled toolbox to combat extremism and terrorism. Other important tools in the fight against extremism are now allocated to regional and community governments.

After the 2014 attack, several municipalities pointed to the fact that Belgium lacked an integrated approach due to limited powers and flawed coordination with its regions. While the federal government was focusing on repressive measures and monitoring the other measures, the regional governments remained silent. After the January 2015 attack in France, however, both the Flemish and Walloon governments called for attention to their respective preventive measures in the fight against extremism. The November 2015 Paris attacks further reinforced the need for enhanced cooperation and additional measures, leading the federal government to approve an additional 18 measures. But tensions between the different communities remain; while some are calling for more independence for the regions, others are calling for the opposite — a refederalization of some powers.

The lack of a strong national Belgian identity and related positive narrative, together with high rates of unemployment and low social standing within the Muslim migrant community, can be considered factors that help explain why so many Muslim migrants have failed to integrate into Belgian society and have fallen victim to jihadi narratives. Molenbeek, a Muslim majority municipality, has gained a reputation of being a jihadi breeding ground, as evidenced by its closed micro-community. The municipality of about 100,000 people is the second poorest in the country, with the second youngest population, high unemployment and crime rates, and a nearly 10 percent annual population turnover that makes it highly transient. In such an environment, recruiters for jihad make pitches to small groups of friends and family. Residential segregation contributes to the radicalization process. The recruiters tell radicals-to-be that they don’t belong in that country, that they are not wanted there, can’t live there and certainly can’t get a job there. In this respect, it is paramount to assimilate immigrant communities in order to prevent potential radicalization.

Recommendations

To counter terrorist narratives aimed at a Muslim audience, Belgium should first develop a credible and legitimate narrative based on a representative national identity. It is important to create a sense of belonging for different immigrant communities in order to facilitate assimilation. This Belgian national identity faces strong negative pressure from increasing regional nationalism and long-enduring cultural fault lines amongst the native population. This undermines the credibility and legitimacy of a single national identity on which to build a narrative. Belgium has three different options regarding the development of an identity-based narrative.

One is to delegate the authority to develop the narrative, as part of the counternarrative, to community governments built on their respective identities. The second option, and the least likely in the short term, is to use this opportunity and the need for national unity to suggest a reverse in state reforms and consider refederalizing certain powers previously devolved to the communities, especially those related to today’s notion of security. The last option is to enhance and structure cooperation between the federal government and regional and community governments to develop a narrative that contains a strong unique identity while respecting the historical composition of the country. In that case, the diversity represented by the different native communities in Belgium could even be regarded as an opportunity rather than a threat.

The biggest challenge is to build a strong response and partnerships against terrorism based on unity and shared values. Now is the time for Belgium to unite in strength against terrorism. Therefore, let us simply work toward the vision expressed in Belgium’s national motto: “Strength lies in unity.”

Comments are closed.