Implications for the Euro-Atlantic World

By Dr. Pál Dunay, Marshall Center professor

The United States has set the themes for international security and also for much of the terminology used globally. It did so with its National Security Strategy (NSS) of 2003, when it announced a Global War on Terrorism, and did so again in the NSS of 2017, which highlighted the challenge of great power competition between the U.S. (along with its friends and allies), and China and Russia. It is still too early to tell whether the friends and allies will align with Washington.

In light of this, and assuming that the U.S. competes with China and Russia globally, there should be a U.S. presence in those parts of the world where one or the other, or both, are active. This means that Central Asia should be a center of U.S. attention, especially because the two great powers adjacent to Central Asia are potential major supporters, investors, trading partners, and assistance and security providers for the region.

It is fair to question whether the mainstream and widely popularized views concerning Chinese (and Russian) influence in Central Asia are founded. Namely, that:

- The two states complement each other’s contributions while they also compete for markets, investment and influence.

- The source of Chinese influence is primarily economic while Russia is the main security provider.

- The channels of influence are primarily bilateral, and regional organizations only play a complementary role.

International security is a far more global concern today than a few decades ago, yet, there is every reason to conclude that physical vicinity continues to matter. In Central Asia, there are questions to be answered: What are the dynamics of relations between China and the five Central Asian states, and are widely shared impressions concerning Beijing’s influence correct? What are China’s aspirations compared with those of the Central Asian states? How does China’s influence in Central Asia compare with that of major Western nations?

Widening Chinese-Central Asian relations

The nearly three decades of relations between China and Central Asia are highly dynamic. China moved from a fast-rising, though still noncentral, player in the international system at the beginning of the 1990s to one of the world’s preeminent powers. In 1992, when the Central Asian states had their first year of independence, China represented 1.71% of the world’s combined gross domestic product (GDP) and had the world’s 10th largest economy. In 2018, China represented 15.86% of the world’s GDP (in nominal terms) and had the world’s second-largest economy, just behind the U.S. and 10% greater than Japan, the country with the third-largest economy.

This is a test of the so-called 24-character strategy declared by Deng Xiaoping in 1990, under which China should “observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.” Beyond the nearly tenfold increase in the size of Chinese GDP, there are two other factors worth considering: 1. The 24-character strategy is not congruent with most of Chinese history, which was based more on the Feng-Gong (tributary) system that linked neighboring states and made them economically dependent. Once economic dependence was achieved, according to Central Asian scholar and Kyrgyz diplomat Kushtarbek Shamshidov, the “Chinese court had political influence and used that state as a buffer zone to protect its territory from outside powers.” 2. The timing of the strategy is intriguing. In 1990, the communist countries were on the defensive, and the socialist “world system” was on its way to collapse. Consequently, a defensive strategy, as outlined by Deng, was appropriate and was not meant to define China’s international policy for a historical era. Moreover, when a state is rising rapidly, it is difficult to resist the temptation to increase its ambition, irrespective of historical tradition, and to seek to regain its status in the international system.

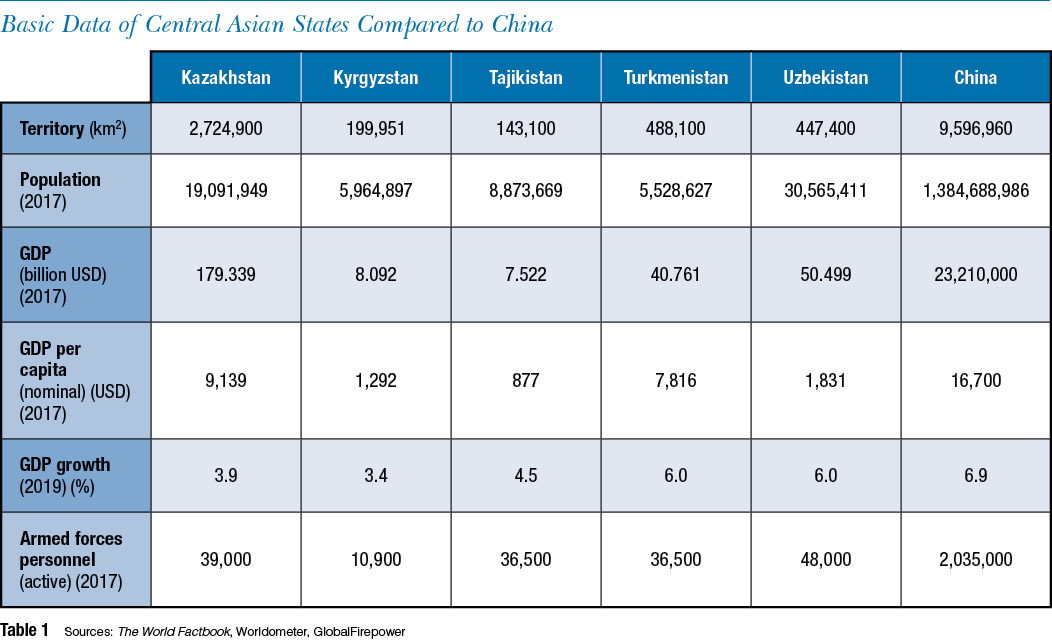

The breakup of the Soviet Union also meant the reemergence of the importance of geographical vicinity. China was at an early stage in its transformation, though still ahead compared to the newly independent Central Asian states. The total GDP of the Central Asian states combined equaled 10.29% of China’s in 1992. In 2019, the GDP of Central Asia reached 2.045% of China’s. This fivefold “decline” does not mean that Central Asia did not develop (though slowly). Rather, it illustrates the extremely impressive enrichment of China compared to that of Central Asia. In terms of purchasing power parity, the wide difference is slightly less staggering, as China had a higher price level in 2019 than the Central Asian states. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have steadily generated account deficits and trade deficits. Uzbekistan demonstrated volatility by imposing high tariffs and nontariff barriers to protect its dependent domestic markets. As this special protection has eased, the trade deficit has increased (see Table 1).

Take a closer look at the Central Asian states in the context of all the successor states of the Soviet Union, and an important conclusion can be drawn. Nearly three decades after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the five richest states in nominal per capita GDP are those producing hydrocarbons — Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan — and exporting them — Belarus reexports some of what it imports from Russia. This means that three decades were not enough to enrich the former Soviet republics through high value-added production and change the economic fundamentals.

Countries with limited domestic capital to invest can develop a significant dependence on foreign direct investment (FDI). In such a situation, states are at the mercy of investors. Some Central Asian economies, in particular those of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are aid-dependent and will remain so for decades to come. This is understandable because the Central Asian states — without the tsarist and Soviet experiments and their largely positive effect on the development of the region, including industrialization, urbanization, cultural elevation and the declared equality between men and women — would be classical developing countries. However, large parts of Central Asia were developed as monocultural economies based on agricultural production and natural resource exploitation ranging from cotton to uranium, something that made sense only in the broad Soviet framework. Still, some industrialization changed the Central Asian landscape, particularly in Kazakhstan, where half the labor force is employed in industry, construction, trade or communications.

Jiang Zemin, Deng Xiaoping and Mao Zedong, during an exhibition in Beijing. China’s emergence as an economic power has changed its relationship with Central Asia. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

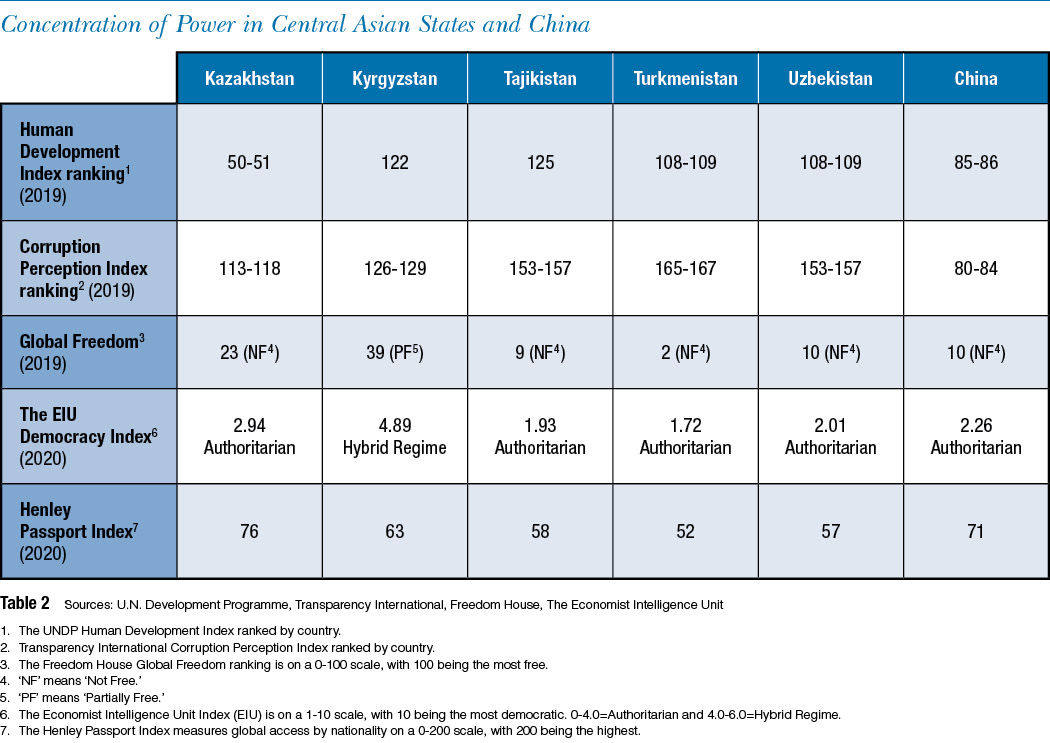

China has been pursuing pragmatic political lines in its international relations founded on well-known principles: noninterference in the internal affairs of other parties, fostering advantageous economic cooperation, and improving its own reputation. In international relations, China aims to fight the three evils — terrorism, extremism and separatism — and to gain acceptance of the “One China” policy. In light of this, China has not set conditions on others when considering cooperation. Understandably, Beijing does not insist on respect for human rights, a condition it does not meet itself. This gives China an advantage compared to those that impose political conditionality. This has been met with satisfaction by the Central Asian states, where such an approach is perfectly acceptable because “regime coincidence” makes China a natural fit and does not require a compromise. China has taken advantage of two facts: 1. High-level political stability has helped establish long-term relations with the people in power. 2. Centralization of power is in a few (in some cases one person’s) hands. Although the two are closely related in the Central Asian context, it is important to mention that power concentration makes it easier to gain influence — including through the use of corrupt political tools such as blackmail and bribery. China benefits from this because many of its investments are carried out by state-owned companies, and even nonstate-owned firms can find themselves in trouble with the extremely powerful Chinese state (see Table 2).

Regarding external trade, the relationship shows large asymmetry. None of the Central Asian states is among the main import partners of China, but Kazakhstan is the 39th largest; China is often the largest (Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan) or second-largest (Kazakhstan) import partner of the Central Asian states. The same goes for exports — the largest, Kazakhstan, is China’s 36th-largest export partner. In turn, China is the largest (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) or second-largest (Kazakhstan) export partner. The case of Turkmenistan is particularly interesting because of its massive export of gas (and very little else). In recent years, China had been the destination of 70% of Turkmenistan’s exports. Turkmenistan noticed how constraining such an asymmetrical dependence can be and in 2018 reopened gas exports to Russia after years of occasionally strained relations.

As far as FDI, China also plays a major role, with variation. The less diversified the Central Asian economy, the less able they are to attract other FDI and the more they depend on Chinese investment. Some of the FDI appears as credit: Turkmenistan will reimburse China for its contribution to building a gas pipeline by supplying gas once the pipeline is operational.

As far as FDI, China also plays a major role, with variation. The less diversified the Central Asian economy, the less able they are to attract other FDI and the more they depend on Chinese investment. Some of the FDI appears as credit: Turkmenistan will reimburse China for its contribution to building a gas pipeline by supplying gas once the pipeline is operational.

Some of the characteristic features of doing business with China include intergovernmentalism, opaqueness, and can involve corrupt relations with leaders. Economic means will be used to create loyalties and dependencies.

All of this leads to several questions. Has Beijing’s significant economic influence turned into political influence? Has that influence compelled states to take positions that they otherwise would not take? Or has it discouraged states from voicing views contrary to those of China? Bearing in mind regime similarity with Beijing and the tendency of Central Asian countries to avoid engaging in the affairs of great powers (unless requested by important strategic partners, more often than not Russia), it would be difficult to conclude that China has to use conditionality and compellence to shape Central Asia’s international position. It is difficult to tell whether the Central Asian governments occasionally feel that they must act (or stay silent) against their best interests under Chinese coercion. This would only be clear if China commented on developments in Central Asia, or if the Central Asian states commented on Chinese developments, in particular the sore points of Taiwan, the South China Sea or the mistreatment of the Uighur minority. However, the parties have thoroughly avoided any public comment that might damage relations.

There is well-founded economic dependence on and political alignment with China in Central Asia. It is the mainstream view that Beijing avoids stepping beyond its traditional means of influence because Russia is a strategic partner also in security. However, as Beijing’s power base has widened in recent decades, it has developed defense procurement relationships with Central Asian states. Although the Central Asian defense market is small, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and Uzbekistan has a special arrangement with Russia. Those four states can purchase Russian armaments and equipment for the Russian national price while largely eliminating the competition from other exporters. Exceptions might apply if a Central Asian state were interested in specialized products that Russia could not supply.

In this framework, China has gradually widened its military interaction with Central Asia. The pattern of its presence is sophisticated and based on mutual advantage. Starting about a decade ago, China assisted with certain supplies, primarily to small and poor Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, to benefit the police forces. This included building a facility to fight drug trafficking in southern Tajikistan. Notably, China has purchased military items from Central Asian states, including 40 Shkval torpedoes in 1998 from Kazakhstan. Because some Central Asian states (Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan) export energy to the Chinese market, military deliveries often take place to reduce a trade surplus. China sold Wing Loong-1 drones to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Tajikistan bought armored combat vehicles and patrol cars. Turkmenistan has a massive trade surplus because of gas exports and bought land-based missiles and mobile radio locator stations. There are Chinese HQ-9 air defense systems in service in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Kazakhstan purchased the Y-8 military airplane, which is similar to the Russian An-12. As the Chinese defense industry has grown more diverse and competitive, China has gradually become a defense exporter with highly competitive prices and delivery conditions, including long-term credit paid back by commodity deliveries — a barter between nations. All these innovations have made China competitive in the Central Asian defense market.

China has also broadened security cooperation with Central Asia. The number of military exercises is on the rise, mainly with the three states it shares a border with: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Some have been carried out within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). China has also established a base in the Nagorno-Badakhshan area of Tajikistan, near the borders of both China and Afghanistan, where a number of training centers and command post facilities have been established. The underlying agreement was signed between the governments in 2016. It is identified as a border guard outpost, built with Chinese money, and servicemen from the Chinese People’s Armed Police serve there. It provides China with information on Afghanistan, which Beijing perceives to be the only major external military challenge to Central Asia, and prevents the movement of Afghan terrorists to China via Tajikistan. China’s preferences in security cooperation can be characterized as pragmatic. Beyond economic interests, China focuses on those areas where it perceives shortfalls and where Central Asian security developments have potential to impact China’s security. They can be linked to the fight against the “three evils,” even though it may require an arbitrary interpretation, such as separatism. Taking into account current tendencies, there is reason to conclude that China has seized the opportunity to broaden its area of activity based on geographic vicinity, economic asymmetry, and in accordance with its increasingly diverse sources of power and influence.

China has also broadened security cooperation with Central Asia. The number of military exercises is on the rise, mainly with the three states it shares a border with: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Some have been carried out within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). China has also established a base in the Nagorno-Badakhshan area of Tajikistan, near the borders of both China and Afghanistan, where a number of training centers and command post facilities have been established. The underlying agreement was signed between the governments in 2016. It is identified as a border guard outpost, built with Chinese money, and servicemen from the Chinese People’s Armed Police serve there. It provides China with information on Afghanistan, which Beijing perceives to be the only major external military challenge to Central Asia, and prevents the movement of Afghan terrorists to China via Tajikistan. China’s preferences in security cooperation can be characterized as pragmatic. Beyond economic interests, China focuses on those areas where it perceives shortfalls and where Central Asian security developments have potential to impact China’s security. They can be linked to the fight against the “three evils,” even though it may require an arbitrary interpretation, such as separatism. Taking into account current tendencies, there is reason to conclude that China has seized the opportunity to broaden its area of activity based on geographic vicinity, economic asymmetry, and in accordance with its increasingly diverse sources of power and influence.

China and Central Asian societies

None of the Central Asian states is a full-fledged democracy. With some variation (Kyrgyzstan is the notable exception), they are autocratic (or outright dictatorial) regimes. Alienating large parts of their population might foster instability and risk the perpetuation of the leaders in power. For this reason, it makes sense to look beyond the interstate level and pay attention to how Central Asian societies relate to China (and occasionally to the Chinese people). There is anecdotal evidence that countries in other regions where China operates have the same reservations as Central Asian countries. There are three aspects to this: 1. A reservation toward China, which as a partner maximizes its advantage without paying attention to local needs. This applies in particular to Chinese investments that do not sufficiently employ local labor. 2. China takes advantage of the asymmetrical relationship and thus realizes unfair advantages. 3. China puts constraints on its partners that prevent them from raising concerns that may be different, if not directly contradictory, to the positions held by Beijing. There is one question that connects all three points: Do Central Asian societies have issues with China or with their own leaders, who may not put the national interest sufficiently ahead of their country’s relations with China? It is difficult to answer this question because the relationships are highly asymmetrical and other external powers are hardly present; therefore, Beijing remains the only viable alternative. Russia could be an exception, but the means it could commit in the long run are more limited. A separate question: Does collusion exist between some corrupt Central Asian leaders and Chinese authorities?

There have been a few cases in the past few years when Central Asian authorities got into trouble for their actions (or inactions) with respect to China. They can be divided into two groups: those involving land use/ownership in Central Asian territory and those involving ethnicity. Problems related to those matters have become more frequent the more intensive interactions have become.

Land ownership and land lease issues have emerged in Kazakhstan-China relations and Tajikistan-China relations. In 2016, the Kazakh Land Code was modified so that foreign entities could also rent land. The change resulted in fairly heated demonstrations after people interpreted it to mean that land ownership could also change hands. Although this was not the case, that can be the impression when properties are rented for a long time. In light of the protests, then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev suspended the application of the code, and the decision was reversed. Although the matter was officially not attributed to then-Prime Minister Karim Massimov (a pro-China politician with university degrees from Beijing and Wuhan), there was suspicion that he was behind the code change as a way to help Chinese economic expansion. In Tajikistan, Chinese farmers have been allowed to lease agricultural land since the early 2010s, raising concerns that this could also result in protests. However, protests were avoided because the land plots were virgin territory and guarantees were given that the agricultural products would be sold domestically and not exported to China. These cases demonstrate how sensitive land issues can become in agricultural countries.

China makes efforts to achieve ethnic homogenization. This presents a challenge — in far Tibet and the Uighur-populated Xinjiang, among other places — because the process takes place without the consent of the minority groups. The latter area is adjacent to Central Asia and Uighur populations also live in Central Asia, in Kazakhstan and in smaller numbers in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. When China acted to speed up ethnic homogenization by opening so-called vocational education and training centers (in fact, reeducation camps), and “schooled” 1 million Chinese citizens if not more, demonstrations started in Kazakhstan. The demonstrations were not confined to the fewer than 200,000 Uighurs in Kazakhstan; they spread more broadly as the impression grew that China was persecuting fellow Muslims. The Kazakh leadership faced a difficult choice because the well-established noninterference policy between the states collided with respect for basic human rights. Kazakh authorities finally chose to address the demonstrators domestically and to not publicly raise the matter in interstate relations with Beijing. This was different from previous Kazakh policy that allowed Astana some room for diplomatic reaction on matters related to the Uighurs. The Kazakh state did everything it could to reassure China and stick to noninterference.

A few months later, in February 2020, ethnic Dungans were persecuted in southern Kazakhstan close to the Kyrgyz border. The Dungans are Muslims of Han Chinese descent, so it was widely assumed to have been an ethnically motivated pogrom. Although this was not the first ethnic clash in Kazakhstan, it was the first involving a Chinese minority, and the clashes resulted in 11 Dungan deaths. These protests, which have until now been confined to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, indicate that Central Asian authorities should pay close attention to social dissatisfaction to avoid social instability. As none of the Central Asian states are full-fledged democracies, established societal conflict management mechanisms may not be sufficient. China must also understand how sensitive an issue its regional domination could become and how it could be instrumentalized by political opposition within the Central Asian states to challenge their countries’ leadership.

Multilateral sugarcoating of bilateral dominance

Great powers such as China usually prefer bilateral relations with their partners because their dominance can be greater and more pronounced. In the past two decades, great powers have preferred intergovernmental organizations that they can dominate or take a role that exceeds their actual influence in the world. China’s fast-rising great power status does not require regional intergovernmental engagement. Still, it participates in a regional (Eurasian) international organization where four of the five Central Asian states are members and the fifth (Turkmenistan) is a regular guest attendee. However, the fact that states assemble in intergovernmental institutions does not fundamentally change power relations. The SCO was established by five countries nearly a quarter-century ago. Until recently, its six members were clearly structured, with China and Russia as dominant players. With the accession of India and Pakistan in 2017, the situation will gradually become more complex because of New Delhi’s geopolitical importance. Although the role of the organization was often overestimated in its first decade and there was speculation that it would lay the groundwork for an anti-U.S. alliance, it continues to serve the interests of its members. Two states have joined, none left (unlike the CSTO that lost members), and the number of observers and dialogue partners is on the rise. SCO meetings matter for Central Asian leaders because they provide bilateral access to their Chinese and Russian counterparts. The reality of multilateral cooperation for the smaller SCO members is in its multi-bilateral core.

Beginning in 2013, China embarked upon One Belt, One Road (OBOR), what it now calls the Belt and Road Initiative, its grand strategy to create a tributary system with Beijing at its center. It is a positive-sum game because Chinese resources are allocated into projects considered necessary by destination and transit countries. Central Asia is an important springboard for the “heartland” dimension of OBOR, while China actively develops its naval dimension (Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road). Central Asia connects China by land with some of its markets in Europe. These countries benefit from infrastructure development, be it highways, railroads, pipelines or electricity grids. This is much appreciated by countries that lack the resources to modernize or even maintain outdated infrastructure. There are some negative points as well. Namely, investments come with influence that may remain benign (support for China’s peaceful development and harmonious world concepts) but can turn malign. Investments come with Chinese labor (which does not stimulate local employment) and often with a Chinese business presence that may amount to a type of neocolonialism. For the poorest Central Asian states, the Chinese resources may well be the only ones available, whereas for the more affluent it provides complementary funding for necessary projects. Consider the $121 million allocated by China to two projects to rebuild and develop the street network in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Some of the funds were not put to good use or “disappeared” (resulting in inconclusive criminal procedures), and in some cases the quality of the rebuilt roads (such as the one between Bishkek and Manas International Airport) was subpar. Yet the work reduced pollution in a city with poor air quality and the city’s main arteries no longer cause damage to the cars driving them. Signs on the buses say they have been donated by China.

It would be false to give the impression that there are no development projects in Central Asia other than those initiated and constructed by China. For example, the Central Asia-South Asia 1000 (CASA-1000) electricity project to export hydroelectricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan is funded by the World Bank.

Implications for the EU, U.S., and Euro-Atlantic world?

In 2019 and 2020, the European Union and the U.S. adopted new Central Asian strategies. These stand out for their realism and limited aspirations. Both the EU and the U.S. are busy in other geographical areas. Central Asia is not among their priorities. The U.S. State Department urges Central Asia to “strengthen their independence from malign actors” and also “to maintain individual sovereignty and make clear choices to achieve and preserve economic independence.” In spite of the careful and diplomatic formulation, it is clear that it is not only terrorists and radical Islamic groups to which the document refers. Those threats do not endanger the economic independence of the five states, but perhaps China and Russia do. The EU largely repeats its old song about cooperation and repeats its expectations. The answers to two simple questions may be more revealing: How much money do the two actors spend in Central Asia? And do they allocate their best human resources there? The U.S. cut its development assistance in half a few years ago, and the EU is not increasing its resources in the region.

Power is relative and not absolute in the international system. Some great powers have reduced their commitment or de facto downgraded Central Asia on their list of strategic priorities. That leaves the Central Asian states with little choice; China remains their best choice when it appears there is no choice at all. Neither the means, nor the will seem to be there to revise this situation in the foreseeable future. However, as COVID-19, the oil slump and a global recession demonstrate, systemic shocks can change strategic calculus. The ability of OBOR to sustain a volume of goods and the perception of connectedness will impact great power competition in Central Asia and the region’s links to China and the Euro-Atlantic world.

Comments are closed.