Europe must engage China to help ensure stability in Egypt

By Col. (Ret.) Mark Stiefbold, U.S. Army, and Dr. Rod Stiefbold

The government of China is uniquely positioned to influence Egyptian stability. A destabilized Egypt would increase the flow of migrants to Europe, resulting in reduced European political and military policy cohesion. Such a result would benefit China’s efforts to establish unilateral agreements with individual European countries and advocate for European acceptance of a China-Russia narrative for ending the Ukraine war. Awareness of these risks does not imply the capability, capacity or policy unity of the European Union to effectively manage them.

Nation-states have a finite capacity to assess and effectively manage complex problems. European leaders and the populaces they represent must concurrently confront a war of attrition on their bloc’s border, refugee-driven irregular migration, stagnant economies and disillusionment with the aspirational goals of a united Europe. Adapting a business term, complex problems inherently are made up of too many interrelated factors for a person to absorb and process. European institutions, made up of competing and factional interests, struggle — much as people do — to combine interrelated factors into aligned and effective policy. How close is Europe to a tipping point? It could be one problem away from irreparably damaging what historian Ian Morris called the “most extraordinary experiment in the history of political institutions.” While that quote dates from 2016 and Britian’s pending referendum on its EU membership, current conditions show that the threat to the ideal of Europe remains. For Europe to succeed, it must mitigate impacts from existing crises while proactively managing future risks. Significant among those risks is the destabilization of Egypt’s government.

Europe is confronting two concurrent refugee crises; one was created by the war in Ukraine and another was caused by instability in several African countries. Excluding those from Ukraine, which is a separate issue, there were 875,000 asylum applications in 2022, up 52% from 2021. In 2023, there were 44% more irregular entries into the EU than in 2022. Egyptians represented only 4% of these entries, though there is potential for their share to become much higher. For example, in 2022, Egyptians were 12.2% of irregular refugees from the eastern, central and western Mediterranean routes. This reflected the collapse of the Egyptian pound after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The devaluation stemmed from the risk — both real and perceived — of an interruption in Ukrainian grain exports to Egypt, spurring an exodus of economic migrants to Europe. Yet, the 2022 stressors on Egypt’s economy pale by comparison with those of 2024.

Egypt remains a destination — if not of choice, then of necessity — for Palestinians, Sudanese, Syrians, and others fleeing conflicts and economic malaise. The approximately 500,000 refugees in Egypt are an added economic burden for Cairo’s government, led by President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi. The newcomers also pose a potential security risk: As extremism expands into the rest of Egypt from the Sinai Peninsula, it provides an alternative for the disillusioned and disenfranchised — Egyptians and refugees alike. Security and economic stability are essential for moderating the flow of refugees. The collapse of the Egyptian government would generate a refugee crisis that could overwhelm Europe, snapping tenuous links of bloc unity.

The seeds of an Egyptian government collapse are sown in the government’s subsidized bread program. A nutrition dependency with early 20th century origins, 67% of Egypt’s 113.8 million residents participate in the program, consuming 9 million tons of wheat per year. With public debt at 89% of gross domestic product (GDP), declining remittances from a global diaspora, 34% inflation and a devalued currency, the Egyptian government cannot feasibly sustain the bread program. Perhaps recognizing this, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), through January 2024, has bailed out Egypt four times in almost eight years, a largess frequency unlikely to abate, so long as global institutions assess it as a state too big to fail. When the IMF said that it and “Egyptian authorities also agreed on the critical importance of strengthening social spending to protect vulnerable groups,” perhaps it was not low- and middle-income households they referred to, but the Egyptian government. For Egypt to end its economic malaise, it must find a deep-pocketed partner with flexibility, if not hostility, to Western mores on economic transparency and personal, civic, political and social rights.

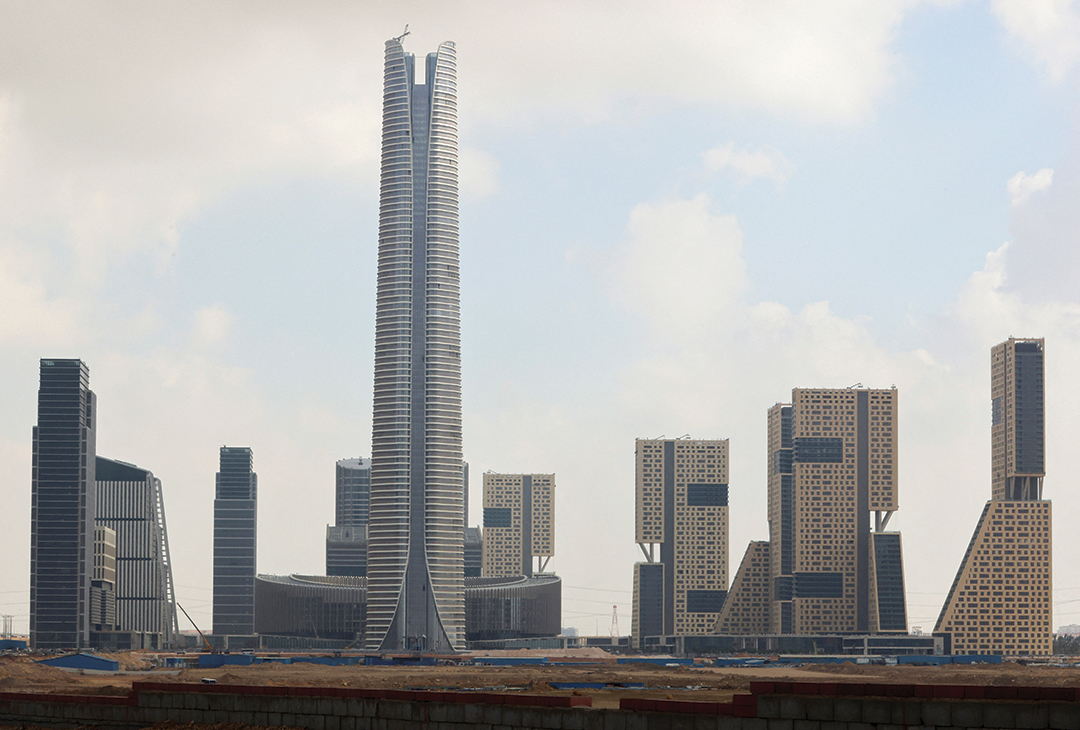

To the EU’s detriment, one such partner is China. Egypt has an enduring relationship with Beijing. They have extensive economic ties, with China being Egypt’s fourth-largest creditor and a facilitator of multiple industrial and trade zones, such as the Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone. The zone, according to Chinese media, generates taxes to Egypt of more than $200 million with nearly 6,000 direct jobs and 50,000 dependent jobs — a modest bright spot in an otherwise struggling economy. Revenue from the Suez Canal hit a record high in Egypt’s fiscal year 2023 at $9.4 billion, with 25,887 ships transiting, an 8.7% increase in traffic from the previous year. As regional tensions increase and act as a catalyst for attacks on civilian shipping, Suez Canal transits have declined, plummeting 45% in the two months after the first attack on Red Sea shipping in November 2023, following the outbreak of hostilities in Gaza. While transits and revenue collected in transit fees will fluctuate with risks, and Egypt will continue efforts to prop up collections through rate increases, the unpredictability of war makes future revenue collections uncertain. During a time of economic stress and uncertainty, Egypt views its friendship with China as essential. Chinese efforts to publicize trade, political engagements and support for statements backing a Palestinian state likely buoy the Egyptian government’s confidence in China. Likewise, the EU can find solace in a separate effect of China’s support of the Egyptian government: stability, and hence no increase in refugees. (Government support and economic and societal stability are not mutually inclusive.)

The EU needs a stable Egypt, and hence the European Commission must recognize and act based on how China would similarly benefit, both economically and in national prestige. For example, China would ensure security for $2 billion in existing China Development Bank Loans and other Chinese foreign-direct investments (FDI) in Egypt. The FDI, in turn, influences regional markets to consume Chinese goods and services, furthering the intent of China’s strategic One Belt, One Road policy (renamed the Belt and Road Initiative). Egyptian national stability also reduces the risk of the government trying to distract or unify its citizens in a fevered pitch of nationalism, which could endanger other regionally significant China-supported projects, such as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Enabling regional stability would demonstrate diplomatic prowess and potentially enable China to displace the United States as the primary diplomatic partner for Middle East-Israel relations.

An alternative course of action for China is to enable, either directly or through nonbenign neglect, a destabilized Egypt. Their assumed calculus would be that the harm done to the EU, and by extension NATO and the U.S., by an unstable Egypt would benefit China. Destabilization would increase economic refugees into the EU, exacerbating the rift between those countries on whose shores they land, and those nations ensconced behind multiple borders — be they political or geographic. Refugees provide EU populists with potent rallying points regarding perceived wrongs enacted by the European Commission. European policymakers, distracted by a refugee crisis, are less likely to unite on policies in conflict with China’s interests. Each of those interests, such as limitless low-duty access to EU markets, tacit support of Russian aggression in Ukraine and toward the Baltic states to distract the U.S. and NATO, and endorsing citizen repression in exchange for government stability, present a crack in the human rights-based governance, economic viability and regional security of the EU.

China’s support for Egypt could further prepare it for a takeover of Taiwan. Though the EU does not recognize Taiwan diplomatically, it does support the island’s inclusion in multilateral forums, such as the World Trade Organization. Policy friction between the EU and China over Taiwan would intensify if the Chinese used an Egyptian government collapse to build military competencies applicable to a takeover. During a pending or actual Egyptian collapse, China could justify increasing its regional forces to protect its funded or owned assets. Such forces could be United Nations-mandated to prevent a humanitarian crisis or descent into violent factionalism. Such a mandate, fulfilled by China, would serve as a force-projection rehearsal, building competencies and scale relevant to a Taiwan invasion. With Egypt’s military assessed as the 15th-most capable globally and having a history of either sustaining or changing the government, such external offers of support might be unwelcome. Egypt, too, gets a voice on how its stability is sustained, a voice that the EU can seek to influence.

As the European Commission seeks to ensure unity in representing the EU’s overall interests, the European Parliament and the many factions within national governments must answer to their citizens. Local grievances arising from domestic and regional factionalism can triumph over enduring EU policies intended to benefit the broader union. This was apparent in the fall of 2023 when Hungary, Poland and Slovakia unilaterally continued a ban on Ukrainian grain imports after the original EU measure expired. Likewise, early 2024 saw Polish farmers continue to protest inexpensive grain imports from Ukraine while France successfully lobbied the EU to act on French farmers’ demands, ranging from limiting Ukrainian imports to relaxing environmental regulations. China indirectly benefits from these actions. Friction, in the form of increased costs and bureaucracy for Kyiv to export grain to the EU, increases grain availability for other markets. While Egypt is traditionally a welcome market for Ukrainian grain, China has the potential to be the stable, creditworthy grain procurer Ukrainian farmers seek. This occurred under the Black Sea Grain Initiative, during which China imported 400% more Ukrainian grain than Egypt. Neither depriving Ukraine of safe-currency grain sales into the EU nor letting Egypt potentially be outbid on the open grain/commodity market is good for the EU’s stated intentions to support Ukraine and stem the flow of economic refugees.

China is the world’s largest consumer of wheat. Egypt is the second-largest importer. As a funding partner for GERD and with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “no-limits friendship” to Russia, China is uniquely positioned to influence Egyptian stability. Specifically, China has the potential to support Cairo’s claims to consistent and sufficient Nile River water flow to support its domestic wheat production. The EU perceives China to have influence with Russia over Ukrainian grain export deals — deals that could benefit Egypt. Note that China has conflicting interests: China was the top destination for agricultural products from the Black Sea Grain Initiative, and so is in competition with Egypt for wheat. Ukraine supplied 22% of Egypt’s imported wheat from 2017 to 2021 and, being more price sensitive than China in their grain purchases, a reduced supply of Ukrainian grain in the global market has a larger negative economic impact on Egypt.

An example of China’s options to support or impede Egyptian stability is its relationship with Ethiopia and the GERD. About 90% of Egypt’s water is sourced from the Nile. Located in northwest Ethiopia on the Blue Nile, GERD is designed to generate 5,250 megawatts of power, with at least 14% funded through Chinese loans. Hence, China has both investments in Ethiopia to protect and an opportunity to support Egypt’s claims for more water security from GERD. Ethiopia’s unilateral approach to filling GERD and its lack of collaboration with Chad and Egypt — the only two Blue Nile states with rights to its water — have increased regional tensions. By potentially offering security guarantees to Egypt in the form of a minimum water supply in the name of humanitarian assistance, China would value Egyptian over Ethiopian interests. Thus, China has multiple means of either helping or harming Egyptian stability. Europe must highlight the advantages to China of being first among equals of countries that enable Egyptian stability. These include a disparate and potentially irreconcilable group of nations, such as China, Russia and the U.S., together with the IMF and other intergovernmental and transnational organizations.

Egypt’s stability is crucial if Europe is to remain a union able to incorporate competing factions without further dissolution. This will require the EU to engage with and influence China. Even where interests are not aligned, their respective goals may be. Most significantly, both China and the EU have domestic economies that are struggling to grow or sustain growth. The European Central Bank is projecting EU GDP growth of 0.6% in 2024, while the National Bureau of Statistics of China is calling for 4.6%, a significant drop from 2023 and more than 25% less than pre-COVID norms. An Egyptian stability crisis would only further depress the GDP of the EU and China by causing further inflationary pressures. Stability also is crucial to the viability of the Suez Canal, Port Said and Suez Port, the canal’s northern and southern terminuses respectively. Without Egyptian stability there is no canal or port security, resulting in higher shipping costs for China’s extensive exports to the EU. As the Ever Given container ship demonstrated in 2021, a single ship can effectively block the canal, halting EU-bound trade. The resulting inflationary shock from rising logistics prices would likely crater already lackluster EU consumer confidence and meager GDP growth targets.

The EU is facing multiple complex and layered issues in need of resolution, each competing for limited resources and awareness. Among these, the potential collapse of Egyptian national stability should be an essential priority. On par with Russian aggression on the union’s eastern flank, the collapse of Africa’s second-largest economy would create an existential threat for the EU. It would not be an army of tanks, drones and other hardware inherent to Russia’s enduring aggression in Ukraine that would be crossing EU borders, but one of economic refugees. To manage this risk, the EU must assess competing Chinese courses of action to support or hinder Egyptian stability. Will China continue to prop up Egypt by keeping the country solvent, watch it collapse through somewhat benign neglect, or actively accelerate the dissolution of Egypt’s government, confident that Beijing will emerge as its savior? There are risks and opportunities for China in each option. For the EU, only Egyptian stability enables success. Hence, the European Commission benefits from engaging both with intergovernmental enablers of Egyptian stability, such as the IMF, and with China, accepting competing methods but potentially aligned interests. The EU and China both benefit from a stable Egypt. Collaboration can bridge other differences and result in mutual success.

Comments are closed.