The West, China and Russia in the Western Balkans

By Dr. Valbona Zeneli, Marshall Center professor | Photos by AFP/Getty Images

In the new era of great power competition, China and Russia challenge Western and trans-Atlantic security and prosperity, not least in the Western Balkans. The region has shaped the history of modern Europe and has been a gateway between East and West for centuries. In recent years, external players have amplified engagement and influence in the region. The authoritarian external presence in the Western Balkans could be classified as “grafting” — countries such as Russia and Turkey with a long history of engagement in the region — and “grifting” — countries such as China and the Gulf states that bring to bear a more commercial and transactional approach.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, which brought bloody conflict to Europe in the1990s, the political West — the United States and the European Union — and its clear foreign policy toward the Western Balkans have been crucial throughout the process of stabilization, reconstruction, state consolidation and, finally, NATO and EU integration. For Western Balkan countries, accession to Euro-Atlantic institutions has been viewed internally and externally as the main mechanism for security, stability and democracy in a troubled region. Albania and Croatia joined NATO in 2009, Montenegro in 2017, and North Macedonia signed its accession document to become the 30th NATO member in March 2020.

Democratization has been the key feature of “Europeanization,” while the “carrot” of membership was used to motivate the political elites in the accession countries to adopt and implement important democratic structural reforms. In recent years, the EU’s appetite for enlargement has waned, commensurate with increased doubts in EU member-state societies about their own institutions, but also because of skepticism arising from the mixed results seen following earlier accessions. The perception that the EU has reached its absorption capacity has gradually created “enlargement fatigue” in Europe’s populations and its institutions, leading to a new “reform fatigue” in the Western Balkans. It has also contributed to a plunge in public support for the integration process.

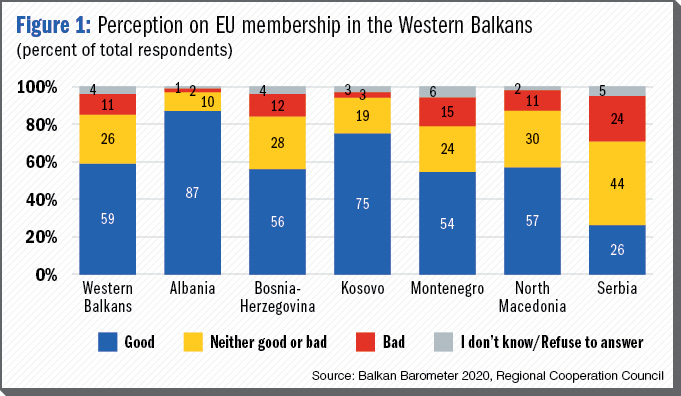

Attraction to the EU is still palpable in the Western Balkans, but it should not be taken for granted. While EU membership remains popular in the region, with 59% public support in 2020, according to the Balkan Barometer survey, there are important variations. Serbia is the only country in the region where EU accession is viewed positively by less than one-third of respondents, and where in fact most of the population likely opposes or is neutral to EU membership. Albania and Kosovo are the two countries with the most support for EU integration, with 87% and 75% respectively. In the case of Kosovo, there is a decrease in EU support compared to 2017 (from 84% down to 75%) as a result of disillusionment over the stalled liberalization process (Figure 1).

The real security challenges in the region stem from the never-ending transition process, through a toxic combination of poverty, unfair rule of law, corruption, organized crime and state capture. All countries in the Western Balkans still fall under the “hybrid regimes” category, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. The chief concerns plaguing the region are unemployment (cited by 60% of the index’s respondents), economic hardship (47%) and corruption (27%).

The real security challenges in the region stem from the never-ending transition process, through a toxic combination of poverty, unfair rule of law, corruption, organized crime and state capture. All countries in the Western Balkans still fall under the “hybrid regimes” category, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. The chief concerns plaguing the region are unemployment (cited by 60% of the index’s respondents), economic hardship (47%) and corruption (27%).

In 2019, average per capita income of the six Balkan countries was only 14% ($6,369, or 5,779 euros) of average EU income ($44,467, or 40,349 euros), according to data from the International Monetary Fund. It seems that the much wished-for economic convergence with the West has stalled. Based on the current outlook for economic growth, the region will need between 70 and 100 years to catch up.

The economic and institutional gap between the EU and the Western Balkans is widening. As a result, people are economically and institutionally motivated to leave the region, attracted by job opportunities and generous social benefits in Western European countries. With regional unemployment rates of 19% in 2019 (very high compared to the 6.3% average EU unemployment rate), an astonishing 39% of people in the region are considering moving abroad. Emigration will continue to play a key role in shaping the region’s future, positively by mitigating unemployment and by generating remittances, which make up 10% of the average gross domestic product in the region, and negatively by contributing to the chronic shortage of skilled workers for domestic labor markets. Brain drain is fast becoming a primary security challenge for the region.

Constituting a market of 18 million consumers, the Western Balkans has the potential for fast-growing economies, easily connected to the common market of the EU. But economic growth is hampered by poorly functioning institutions, informal economies, poor infrastructure, low productivity, low competitiveness and lack of regional integration. The six countries taken together have attracted less than 0.23% of the stock of global foreign direct investment (FDI), where the EU is the biggest investor and assistance provider in the region.

While EU membership is a strategic foreign policy objective for all countries in the region, local elites often favor Euro-Atlantic integration for political gains, with little meaningful commitment to core European liberal democratic values. This adds to people’s frustration with EU support for “stabilocrats,” who pay lip service to costly normative alignments with the EU while failing to seriously address issues of transparency, rule of law and accountability. Unfortunately, the EU has not been critical enough when it comes to regression of democratic reforms, prioritizing stability over democracy. The recent decision by the European Council to open negotiation talks with Albania and North Macedonia sends an optimistic signal to the region and reduces maneuvering room for politicians who were using enlargement fatigue as a scapegoat not to press ahead with reforms.

Russia in the Western Balkans

Increased Russian influence, and the arrival of Chinese influence, in an era of great power competition in the world, shows that the Western Balkans is in play in a new competition between the free and democratic world and the autocratic powers. In 2017, then-EU High Representative Federica Mogherini openly voiced the new concerns that “Moscow’s presumable goal is to loosen the region’s connection to the EU and present Russia as an alternative to a dissolving union.”

An op-ed by U.S. Sen. John McCain, published in The Washington Post in April 2017 after a trip to the Western Balkans, raised alarm in the U.S. about Russian ambitions in the region. He noted, “Perhaps most disturbing of all is Russia’s intensifying effort to assert its malign influence in the region and to prevent the nations of Southeastern Europe from choosing their own futures.”

In a confluence of geopolitical and economic interests, Russia’s engagement and visibility in the region have amplified its objective to project power as a global player, widen its footprint and create a new area of geopolitical rivalry with the West. In reality, Russia has always been present in the region, and after the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the resulting wars, has been closely involved in peace processes and other international mechanisms for the management of the post-conflict period, becoming even more vocal in Balkan affairs over the course of the 2000s. Beyond its abstract influence, Russia has strong economic interests in the region in the form of energy transportation routes and arms control.

In recent years, it became clear that the Kremlin’s strategy is not only to maintain and increase its influence in the region, but also to disrupt the process of NATO and EU integration by exploiting the weak institutions and actively politicizing and exacerbating existing ethnic and religious tensions. Moscow’s increased influence, acting as an opportunistic spoiler to exploit internal weaknesses, brought new concerns about the consolidation of the democratic transition in the region.

Through a mix of hybrid tools, Russia is acting to increase its influence through corruption, coercion, business activity and state propaganda, with the objective of destabilizing the region and stalling its Euro-Atlantic integration. The Kremlin, to achieve its objectives, has used cultural tools and religious influence among the Orthodox communities, exerted its energy leverage, waged disinformation campaigns and deployed its intelligence services. The Western Balkans is a new bloc of Russian interest, but its strategy for achieving foreign policy goals is no different than that used in Eastern Partnership countries.

The strategy focuses on the most vulnerable segments of the population to promote friction and fragmentation, and on eurosceptic groups in local societies, with the aim of weakening the EU’s power of attraction. Countries that have large segments of population that are eurosceptic or neutral about EU enlargement prospects are the most vulnerable, such as Serbia (where 59% of the population is eurosceptic or neutral), Bosnia-Herzegovina (48%), and North Macedonia and Montenegro (both 45%), according to the Balkan Barometer 2019 public opinion survey.

Serbia is Russia’s main partner and the hub of Russian influence in the Western Balkans, based on long-standing cultural and historical ties; however, Russian influence stretches across the entire region. The Serbian population views Russia very positively, with more than 72% in favor of the alliance, and is supportive of even closer ties with Moscow, according to a 2016 survey conducted by Nova Srpska Politička Misao magazine. Belgrade is Moscow’s closest ally, not only refusing to apply EU sanctions after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea but also signing a free trade agreement with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union, despite harsh criticism from the EU. Moscow’s opposition to Kosovo’s independence has helped maintain its popularity and leverage with Belgrade and the ethnic Serbian population throughout the Balkans, such as in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro. Moscow impedes the normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia by meddling through dangerous rhetoric and spreading propaganda about clashes between a “Greater Albania” and a “Greater Serbia.”

Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina also have strong cultural links with Russia through the Orthodox Church. Russian language centers have proliferated in the region in recent years, supported by the Russian state-funded Russkiy Mir Foundation. Russian state media is also very active in the Western Balkans, with channels such as RT and Russia 24 regularly included in cable packages. The main platform is the Sputnik branch in Serbia, whose content spills out through Serbian news outlets and from there throughout the region, reaching even countries such as Albania and Kosovo. In a near-perfect example of hybrid warfare, the Kremlin can apply political leverage by stoking division and social tensions, and most importantly fostering cynicism about democratic and Euro-Atlantic institutions, all at little financial cost.

The Kremlin publicly opposed Montenegro’s membership in NATO, allegedly even supporting a failed coup attempt in late 2016 to block the process — one of the most-high profile examples of malign Russian influence. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov had previously openly condemned the desires of Montenegro (representing the last section of the Adriatic coastline not held by a NATO country), North Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina for NATO membership as “mistaken politics and provocation by the North Atlantic military alliance.” The Kremlin has vocally supported Bosnian Serb-controlled Republika Srpska’s leader Milorad Dodik’s efforts to separate from the Bosniak- and Bosnian Croat-controlled Federation, and break up Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In North Macedonia, Russia increased its meddling significantly by exploiting the constitutional crisis in the country in 2018. Moscow even accused the EU and NATO of creating the crisis. Interference continued during negotiations over the name change to North Macedonia and the following referendum campaign over acceptance of the new name. The Prespa Agreement, finalized in June 2018, brought to an end the 20-year dispute between Athens and Skopje and opened the way for North Macedonia’s NATO membership. Although North Macedonia was successful in its NATO membership bid, becoming the 30th Alliance member, and the EU Council has given the greenlight to open negotiation talks with North Macedonia and Albania, nationalist and political opposition to the name change remain, and it is likely that Moscow’s disruptive efforts will continue.

In North Macedonia, Russia increased its meddling significantly by exploiting the constitutional crisis in the country in 2018. Moscow even accused the EU and NATO of creating the crisis. Interference continued during negotiations over the name change to North Macedonia and the following referendum campaign over acceptance of the new name. The Prespa Agreement, finalized in June 2018, brought to an end the 20-year dispute between Athens and Skopje and opened the way for North Macedonia’s NATO membership. Although North Macedonia was successful in its NATO membership bid, becoming the 30th Alliance member, and the EU Council has given the greenlight to open negotiation talks with North Macedonia and Albania, nationalist and political opposition to the name change remain, and it is likely that Moscow’s disruptive efforts will continue.

Russia challenges efforts to consolidate democratic transition in the Western Balkans by supporting illiberal tendencies and populist elites and promoting alternative paradigms. Some Western Balkan leaders seek to leverage “the Russian challenge” to extract concessions from Western partners while paying lip service to reform efforts.

China in the Western Balkans

In accordance with Beijing’s economic and geopolitical agenda in Europe, the Western Balkans has seen an increased Chinese footprint, raising concerns in the West that in an era of great power competition, as Mogherini said, “the Balkans can easily become one of the chessboards where the big power game can be played.” China’s approach is more subtle than Russia’s, but its ambitions may be more significant — to gain access to the EU through its backyard. While skepticism of Russia in the region has increased, attitudes toward China remain open.

Despite offering a paucity of viable market opportunities to Chinese investors, the five Western Balkan countries — Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia (Kosovo is excluded as not recognized) — have been included since 2012 in China’s 16+1 platform (now 17+1 with the addition of Greece) for economic engagement with East and Southeast Europe. Later, this regional platform became an integral part of China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) program, and the Western Balkans were increasingly targeted for OBOR-related projects as a result of their key strategic geographical position — a Balkan Silk Road of infrastructure networks and logistical corridors between the Port of Piraeus in Greece (Beijing’s flagship project in the region) and markets in Western Europe. Beijing aims to use the region as a commercial gateway and transit platform to Western Europe, where China’s real interests lie.

Despite offering a paucity of viable market opportunities to Chinese investors, the five Western Balkan countries — Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia (Kosovo is excluded as not recognized) — have been included since 2012 in China’s 16+1 platform (now 17+1 with the addition of Greece) for economic engagement with East and Southeast Europe. Later, this regional platform became an integral part of China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) program, and the Western Balkans were increasingly targeted for OBOR-related projects as a result of their key strategic geographical position — a Balkan Silk Road of infrastructure networks and logistical corridors between the Port of Piraeus in Greece (Beijing’s flagship project in the region) and markets in Western Europe. Beijing aims to use the region as a commercial gateway and transit platform to Western Europe, where China’s real interests lie.

China has used easy money and soft power (confidence-building initiatives, cultural exchanges, media presence and Confucius Institutes) to gain influence rapidly, taking advantage of the lack of infrastructure in the region, combined with a lack of capital, loose regulations, lax public procurement rules and poor labor regulations. All these factors make it easier for Chinese investors looking to easily establish bases and invest in the EU’s backyard.

Capital rich and ready to outspend many Western actors, who are deterred by the questionable business environment in the region, Chinese companies — mainly state-owned enterprises — maintain a distinct advantage because they are supported by large government subsidies and state banks, and are willing to build at low costs without the stringent (and costly) requirements of meeting environmental and social standards.

Chinese projects can be easily aligned with political cycles and when coupled with top-down, rather than transparent and market-driven, procurement decisions, Beijing’s patronage allows decision-makers in the region to fuel patronage networks and boost short-term electoral advantages.

Political behavior also shapes public perception, which is shifting in favor of China. Few in the Balkans worry about the domestic situation in China, and the geographical distance plays in Beijing’s favor. With the aim of building a cohort of friendly countries, Beijing is heavily investing in cultural diplomacy, from the Confucius Institutes present in every capital in the region to chambers of commerce and cultural centers. The key driver of China’s clout is the appeal of its development model, which utilizes capital as an economic miracle-maker, raises expectations and romanticizes its ability to bring wealth to the Western Balkans.

Trade relations: China and Russia vs. the West

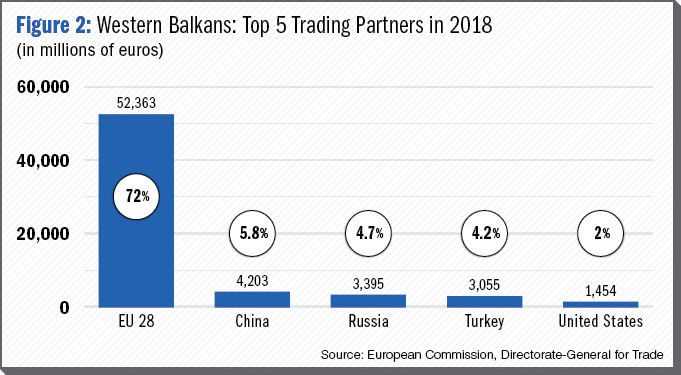

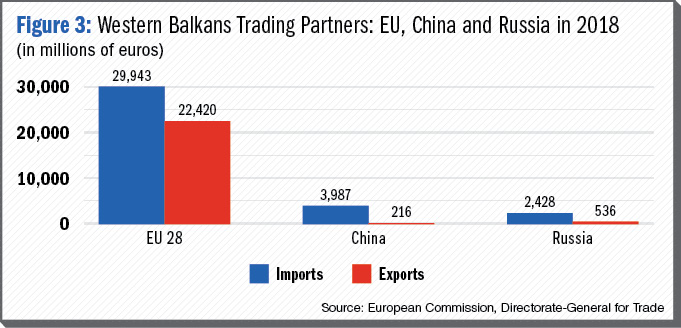

When it comes to trade with the Western Balkans, the Russian and Chinese presence is limited compared to the EU’s. In 2018, almost 72% ($57 billion, or 52 billion euros) of the region’s $80 billion (73 billion euros) in foreign trade was with the EU; more specifically 84% of exports and 64% of imports, according to data from the European Commission (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Trade relations between the EU and the Western Balkans have increased rapidly in the last decade, up from $34 billion (31 billion euros) in 2008.

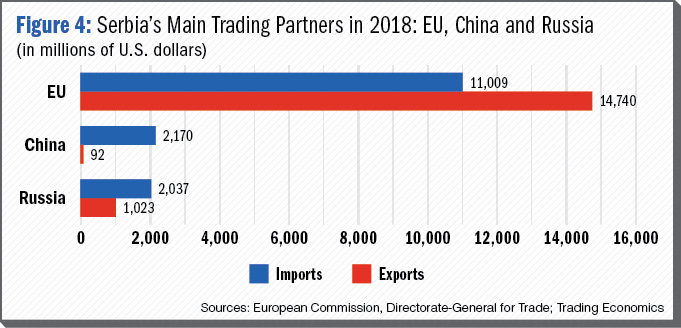

China has quickly become the region’s second-largest trading partner, but with $4.5 billion (4 billion euros) in 2018, it accounts for only 5.8% of overall regional trade, and almost half of that is with Serbia ($2.2 billion, or 2 billion euros), China’s strategic partner in the region. To put it in perspective, trade with the Western Balkans is only 4.3% of China’s total trade with the 17+1 platform, $103 billion (92.2 billion euros) in 2018, according to UN Comtrade data. Russia (4.7%) is the third largest trading partner for the region and the trend has been a decline over the last decade. The other two main partners are Turkey (4.2%) and the U.S. (2%).

Russian investment: Energy, real estate, and banking

Russian investment in the Western Balkans is low compared to that of the EU, which makes up more than 70% of total FDI in the region. However, the West has overlooked the challenges that kleptocratic Balkan networks represent to sustainable economic growth and free-market competition in the region and underestimated Russian investment. It is true that Russian FDI is very low compared to that of the EU as a whole, but if we take countries singularly, Russia is an important player. But actual Russian FDI is also sometimes channeled through subsidiaries in other European countries, and from offshore zones and tax havens. Most importantly, even if the quantity of Russian FDI is limited, it is focused on strategic sectors, such as energy, banking, real estate and metallurgy. Most Western Balkan countries are dependent on Russian energy, which gives Moscow remarkable influence in Serbia, North Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where Russia covers 100% of gas demand.

In small countries with nondiversified economies, Russia can concentrate its economic influence in sectors that are sources of economic growth, such as the real estate and tourism sectors in Montenegro. Russia is the largest single investor in Montenegro, with 13% of FDI out of total 2018 FDI of $5.6 billion (5 billion euros), which accounts for 30% of the country’s GDP, according to data from the Central Bank of Montenegro and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). It is estimated that 70,000 properties in Montenegro are owned by Russians (compared to just 7,000 permanent residents from Russia). Over the past 10 years, Russia has accounted for an average of 17% of FDI inflow into Montenegro, varying from only 4.3% in 2009 to 30% in 2013.

In Serbia, Russia accounted for 9% total FDI in 2018, almost $40 billion (35.8 billion euros), according to data from the Central Bank of Serbia. These investments are focused mainly in the banking sector and the energy sector, where the Russian giant, Gazprom, has owned a controlling stake in Serbia’s state oil company, NIS, since 2008 and Russia’s Lukoil is one of the main players in the wholesale distribution networks. More than 1,000 companies in Serbia are entirely or partially owned by Russians, employing 2% of the workforce and making up 13% of the revenues of the domestic economy. Government-to-government loans have also played an important role, such as the $500 million (447.8 million euros) loan from Russia to help offset the recession in Serbia, and later, another $800 million (716.4 million euros) for modernizing railway infrastructure (Figure 4).

Similarly, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Russian FDI makes up 8% of $8.3 billion (7.4 billion euros) total FDI and 3.3% of total gross domestic product (GDP), according to the Central Bank of Bosnia-Herzegovina, where it is focused on the oil and gas sector and controls the country’s two refineries, both in Republika Srpska. In North Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo, Russian investment remains very low, but it is important to understand that some FDI may not be attributed to Russia, since it could come through other European countries or tax heavens.

China’s strategic Balkan investment

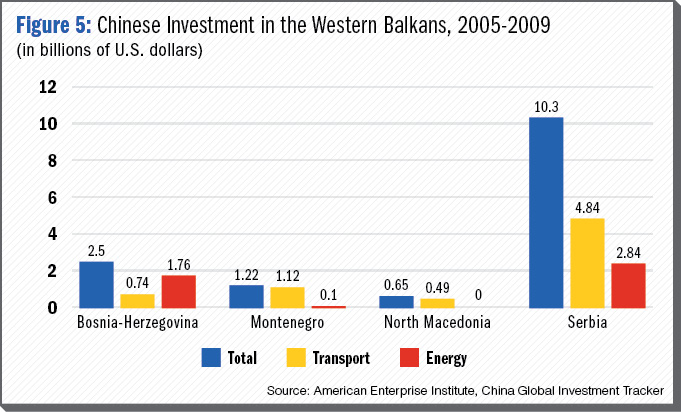

Chinese investment (greenfield investment and contracts) in the Western Balkans (excepting Albania) during 2005-2019 was $14.6 billion (13.1 billion euros), with Serbia leading with $10.3 billion (9.2 billion euros), according to China Global Investment Tracker data from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). This equals 20% of total FDI in the region ($72 billion, or 64.5 billion euros), according to UNCTAD. A misleading aspect of the reported data is that most of the money is not actual FDI, but loans. In fact, most Chinese economic engagement in the region amounts to lending for OBOR-related infrastructure projects, mainly in transportation and energy. According to AEI’s data, about half ($7.2 billion, or 6.5 billion euros) of the Chinese money in the Western Balkans goes toward transport and infrastructure contracts financed by Chinese banks. Another $4.7 billion (4.2 billion euros) is investment in the energy sector, financed by loans. More than 80% of total Chinese investment in the region is financed by loans (Figure 5).

Among the biggest projects in the region is the Belgrade-Budapest railway, 85% ($2.5 billion, or 2.2 billion euros) financed by China Export-Import Bank and constructed by China Railway and Construction Corp. In 2016, China’s state-owned HBIS Group took over the steel mill in Smederevo, Serbia, at a price of $55 million (49.3 million euros), which had earlier been sold by U.S. Steel back to the Serbian government for a symbolic $1.

Among the biggest projects in the region is the Belgrade-Budapest railway, 85% ($2.5 billion, or 2.2 billion euros) financed by China Export-Import Bank and constructed by China Railway and Construction Corp. In 2016, China’s state-owned HBIS Group took over the steel mill in Smederevo, Serbia, at a price of $55 million (49.3 million euros), which had earlier been sold by U.S. Steel back to the Serbian government for a symbolic $1.

Serbia also sees China as a major foreign policy partner, after completing a signature $3 billion (2.7 billion euros) package of economic and military purchases. Serbia is becoming an increasingly important hub for China’s digital Silk Road, as it aims to inherit the role of regional leader in digitalization and to become a focal point for future initiatives by Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei. In 2017, Huawei signed a contract with Belgrade to provide Safe City surveillance equipment to Serbian cities, consisting of 1,000 high-definition cameras in Belgrade alone, and to establish the Huawei Innovation Center for Digital Transformation.

The new Bar-Boljare highway in Montenegro, which will be part of a highway system eventually connecting Belgrade with the Montenegrin port city of Bar, is financed by the state-owned Export-Import Bank of China, which loaned 85% of the estimated $1 billion (900 million euros), since increased to $1.1 billion, and is being built by the China Road and Bridge Corp.

In North Macedonia, two highways — Miladinovici to Shtip and Kichevo to Ohrid — cost $580 million (519 million euros) and are being built by Sinohydro Corp. Ltd. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the national electric power company Elekropriveda received a $700 million (627 million euros) loan from China’s Export-Import Bank to finish the thermal power plant in Tuzla, to be built by three Chinese companies, a project that the EU has criticized on grounds of increased pollution.

In Albania, China’s state-backed Everbright Group acquired Tirana National Airport, and Geo-Jade Petroleum Corp. bought the largest oil refinery in the country, accounting for 95% of Albania’s crude oil, for $442 million (396 million euros).

Beijing has boasted of the “win-win” salutary effects of its OBOR investments, but this narrative is belied by the economic realities of the region. Economic cooperation is typified by the use of Chinese loans for infrastructure development, Chinese state-owned enterprises, Chinese workers, and the spread of Chinese labor and environmental standards, which are distinctly weaker than those of the EU. Chinese firms profit from often unsustainable deals, as sovereign guarantees shift risk onto host countries at the expense of financial stability.

Beijing has boasted of the “win-win” salutary effects of its OBOR investments, but this narrative is belied by the economic realities of the region. Economic cooperation is typified by the use of Chinese loans for infrastructure development, Chinese state-owned enterprises, Chinese workers, and the spread of Chinese labor and environmental standards, which are distinctly weaker than those of the EU. Chinese firms profit from often unsustainable deals, as sovereign guarantees shift risk onto host countries at the expense of financial stability.

What the current Chinese-led infrastructure projects in the region have in common is low financial and economic viability. Without rigorous financial evaluations and due diligence, some Western Balkan countries risk getting trapped in debt servitude to China. As of 2018, new NATO member Montenegro owes almost 40% of its debt to China, while North Macedonia owes 20%, Bosnia-Herzegovina owes 14% and Serbia owes 12%.

Implications for Europe

In an era of great power competition, the Western Balkans can easily become a chessboard where big power games are played. Stabilizing the region and bringing it closer to trans-Atlantic core values, norms, institutions and democratic models of governance should be a top priority for the EU and the U.S. The increased presence of Russia and China in the Western Balkans represents a long-term challenge for the region and for trans-Atlantic security. The increased Chinese and Russian footprints in Europe challenge concepts of traditional economic and geopolitical practices not only in Europe, but throughout the trans-Atlantic economy.

Deeper Chinese and Russian footprints would strengthen alternative development models and challenge democratization efforts in the Western Balkans and, as a result, EU integration. By exporting its domestic economic practices, especially to the EU accession countries of the 16+1 platform, Beijing presents itself as an alternative to the liberal Western model and as a competitor to the U.S. The OBOR expands competition beyond the economic, diplomatic and military domains and into an ideological competition between Western free-market capitalism and Chinese state-driven mercantilism.

Weaker institutions in the Western Balkans seem less likely to resist Chinese coercion through investment and Russian pressure through leverage. Creating divisions in the Western Balkans, and in Europe more broadly, aims to divide and conquer and paralyze the decision-making process inside the EU and ultimately to prevent Europe from joining any U.S. effort to check their global influence.

Both the U.S. and the EU have realized that strategic competition with China is now a reality. EU references to China as a “systemic competitor” represent a conscious recognition of the changing calculus in the trade-off between economic benefits and security concerns.

The West needs to provide better options for the Western Balkans. Only a determined EU integration process will keep the region on track — for the benefit of its citizens, its leaders and the European community. Opening EU accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia will send an important and encouraging signal to the entire region, offering a much-deserved EU perspective to the citizenry in the region, but it will also hold the political leadership in the Western Balkans accountable for rule of law, transparency and good governance. In collaboration with the U.S., the EU needs a clear strategy to develop economic opportunities built upon the foundations of the rule of law and good governance, articulating a vision of a Europe whole, free and at peace. Both the EU and the U.S. should compete for more influence in the region, engaging not only with policymakers, but with wider societies. As the main donors in the region, they should better leverage their investments while enhancing and integrating strategic communications to ensure the public understands the purpose and benefits of the assistance.

The EU’s Europe-Asia Connectivity Strategy, published in late 2018, which aims to strengthen digital, transport and energy links between Europe and Asia to promote development and provide alternatives to the OBOR includes the Western Balkans but does not come with any funding attached. There should be stronger synergies between EU assistance programs and U.S. initiatives, such as the U.S. Build Act of 2018, aimed at creating a new financial development institution with a $60 billion (53.7 billion euros) budget for investment in developing countries. The Three Seas Initiative, another important program that aims at fostering economic development, upgrading infrastructure and enriching trans-Atlantic ties, should be extended to the Western Balkans. Synergies should be sought between the Berlin Process and the Three Seas Initiative.

Western structural and infrastructure investments should also come with stronger conditionality for good governance and increased transparency to improve the current regional business environment, achieve tangible change and attract much needed foreign investment. These efforts will result in good investments that will pay dividends for generations to come. What direction the Western Balkans will take depends on the EU’s geopolitical vision, as well as the political will of the countries in the region, to undertake serious democratic reforms.

Comments are closed.