Navigating the Gulf States’ Energy Strategies

By Dr. Farkhod Aminjonov, National Defence College, United Arab Emirates

Arabian Gulf countries, as major net hydrocarbon exporters, have long played a significant role in supplying the energy that fuels socioeconomic growth and reinforces global energy security. Now, the region — also known as the Persian Gulf — is emerging beyond its traditional role of key player in the fossil fuel-dominated world into a potential driver of global energy transition.

To reflect these shifts in their energy strategies, Gulf states have developed policies that evolve around three orders of energy interest. Their default interest is to reinforce the predominance of fossil fuels in the global energy system. Their second is to maximize the space for hydrocarbons while still being part of climate solutions. The third is to align with mainstream policies driving the global transition. While these orders of energy interest may appear mutually exclusive, Gulf nations are effectively advancing various vectors of engagement in pursuit of seemingly divergent energy objectives.

In an environment of rising geopolitical and geoeconomic uncertainty, Gulf states are attempting to exercise a greater degree of agency in their foreign policies to address energy security risks and manage the global energy transition. Conflicts such as the Russia-Ukraine war and instability in the Middle East have accelerated the transition away from fossil fuel-based energy systems and, to some extent, altered global energy supply dynamics, but these developments are unlikely to trigger major shifts in the Gulf’s strategic energy priorities, which are now focused on the Indo-Pacific market. However, the Gulf’s current energy strategies will have a significant impact on shaping strategic partnerships with European nations.

Three orders of interest

The Gulf nations’ traditional and default interest has been to reinforce the leading role of fossil fuels — particularly oil and gas — in the global energy system by implementing strategies aimed at delaying the transition from such fuels for as long as possible. The underlying reasons are not hard to comprehend. The Gulf is a major stakeholder in a global system that depends on oil and gas for 55% of its energy demands. The region is home to almost half of the world’s oil reserves, accounts for one-third of global oil production and is the largest source of crude oil exports. The region also boasts the world’s largest share of gas reserves (40%) and is home to one of the largest producers of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Oil and gas revenues constitute more than 60% of government budgets for Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, more than 70% for Oman, and more than 80% for Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Therefore, a rapid transition away from hydrocarbons is likely to significantly harm these countries’ economic growth and welfare. By extension, such a development could also affect the stability of regimes that heavily rely on oil- and gas-export revenues.

The Gulf states have been continually increasing energy extraction, refining capacity and petrochemical output in the past decades. Plans to further boost hydrocarbon production will result in higher exports, but also higher emissions. The Gulf nations’ energy interests are shaped by the desire to maintain their fundamental role in the global energy trade, and by opposition to mainstream views on human-caused sources of climate change. Even though all Gulf states have signed and ratified the Paris Agreement, the environmentally damaging hydrocarbon industry continues to expand throughout the region. Because of the region’s excessive dependence on hydrocarbons and support for policies that encourage expansion of this sector, Climate Action Tracker rates all Gulf nations’ efforts as critically insufficient to meet their climate commitments. In addition to attempts to move to the forefront of the energy transition and climate-change impact mitigation efforts, the UAE plans to increase energy capital spending ($150 billion) for the period of 2023-2027 in upstream oil and gas exploration and development. Gulf nations continue to invest significantly in refineries and petrochemical facilities abroad to ensure stable demand for their crude oil and natural gas over many years. This long-term strategy helps secure their market position and guarantees a consistent flow of revenue.

As Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency (IEA), pointed out, every energy company will be affected by the energy transition and will have to respond in one way or another. A key question is whether oil and gas companies should be viewed as part of the problem or could become key actors in solving it. Apparently, Gulf states have decided to maximize the diminishing space for hydrocarbon use to thrive while being part of the climate solution by advocating for lower-carbon and lower-emission oil and gas industries. This second order of energy interest reflects the Gulf states’ willingness to contribute to positive climate solutions as long as they can reframe the antifossil fuel perspective.

The second order of energy interests is predicated on a level of divergence from supporting the fossil fuels industry, but not to an extent that would break with the status quo. This strategy is illustrated in the “balanced” approach to energy transition that concurrently ensures sustainability, energy security and economic prosperity for the oil- and gas-rich Gulf nations. A statement made by the president of the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) and UAE’s special envoy for climate change, His Excellency Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, who is also the minister of industry and advanced technology, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. (ADNOC), and chairperson of the Masdar Co., perfectly illustrates the Gulf’s energy priorities: “The work focus should be on stopping emissions and not abandoning the current energy system before the future energy system is ready.”

The leaders of the Gulf states recognize that certain state-owned enterprises have the potential to succeed in a lower-carbon economy. Saudi Aramco and ADNOC currently rank among the top five upstream hydrocarbon companies globally in terms of low carbon dioxide emission levels. With marginal costs of extraction at $3 and $7 per barrel of oil, the two companies are in favorable positions to incorporate oil into the ongoing energy transition. In 2021, Qatar agreed to spend $200 million on emissions reduction technology for the expansion of its giant North Field gas field that will result in a product with 30% less emissions than other competing sources of LNG. Saudi Aramco announced plans to capture the lion’s share of blue hydrogen demand by 2025, and it was the first to export blue ammonia to Japan in 2020 and to South Korea in 2022. Qatar also is planning to build the world’s largest blue ammonia plant to produce 1.2 million tons per year. The implication of the Gulf energy giants’ second order of energy interests is, therefore, to promote the production and consumption of oil and gas with lower emission levels that can be achieved through carbon-capture technology, resource circularity and hydrogen development.

Some Gulf states have also adopted a third-order interest strategy to align themselves with certain mainstream policies and norms associated with the energy transition. This is far from their preferred response to a transition away from hydrocarbons. What support there is for this strategy tends to be government driven and conditioned by economic diversification and intangible benefits related to prestige and modernity. Gulf states cannot overlook the significant change in foreign direct investment trends in the global energy system, which now favor nonfossil fuel ventures.

In line with this strategy, the Gulf oil and gas giants are institutionalizing their commitments to clean energy transition and climate change mitigation, and to adaptation efforts by participating in international meetings and promoting domestic clean energy initiatives. All Gulf states are signatories of the Paris Agreement, with the UAE being the first country in the Middle East to sign it. They have submitted updated versions of “nationally determined contributions” and adopted national energy strategies that outline and communicate each country’s climate goals, which in the case of Saudi Arabia and the UAE contain more ambitious targets. They have also rolled out, albeit at varying paces, large-scale domestic renewable energy projects. With a 2-gigawatt capacity, Al Dhafra Solar PV is the world’s largest single-site solar power plant and one of the groundbreaking renewable energy projects implemented by the UAE. When completed in 2030, the world’s largest single-site solar park — Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park — will reach a capacity of 5 gigawatts. Abu Dhabi hosted the International Renewable Energy Agency in October 2024 and Dubai hosted COP28 in late 2023. Since 2006, the UAE’s Masdar Co. has invested over $20 billion in 30 countries for the development of 11 gigawatts of solar, wind and waste-to-energy power generation projects. These are a few examples of the Gulf nations’ ambitious energy and economic diversification targets.

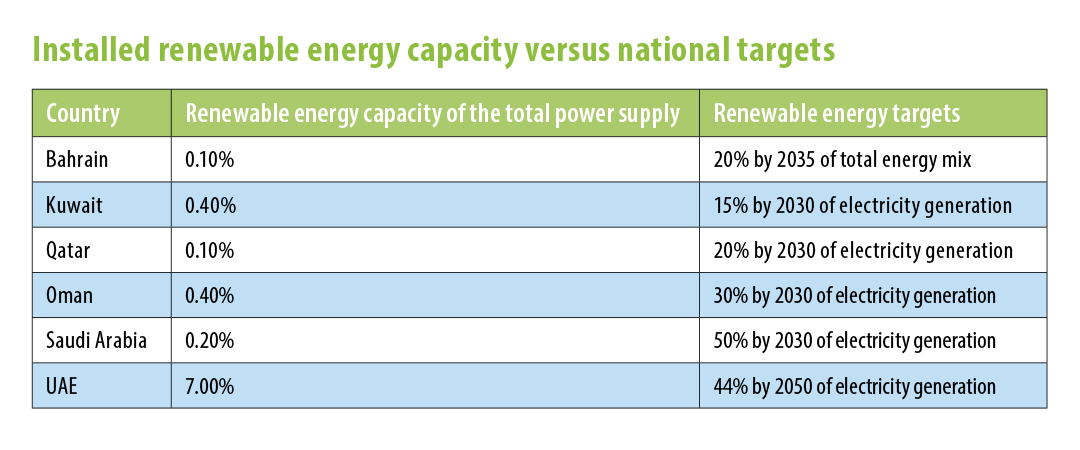

Saudi Arabia has developed its Vision 2030 economic plan to introduce 60 gigawatts of renewables to the overall energy balance by 2030. If realized, these plans will turn the world’s largest oil-exporting country into one of the largest contributors to global decarbonization efforts. The UAE is offering the lowest bids for renewable energy projects to accelerate the transition; it aims to achieve 44% power generation from renewables by 2050, up from about 7% today. As indicated in its Green Initiative program, Saudi Arabia has even more ambitious targets, aiming to transition 50% of its energy needs to renewable sources by 2030. The regional leaders boast a large reserve of cost-competitive and often low-carbon-intensity supply and are well positioned to compete for buyers. Yet, considering the role Gulf nations play in the global oil and gas supply chains, it is not surprising that they have always had and will continue to have a challenging relationship with energy transition and climate change.

Oil- and gas-rich Gulf states mostly resisted accelerating the energy transition and joining pro-climate endeavors before COP26. Then, an unexpected turn occurred with the Gulf nations’ decision to place climate and clean energy commitments at the center of their energy and economic development strategies through net-zero emissions pledges. In 2021, the UAE was the first Gulf nation to pledge net-zero emissions by 2050. Net-zero pledges by 2060, from Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, followed. At COP27 in 2022, Kuwait and Oman pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Critics of the Gulf states’ climate change policy planning say that these pledges have been largely driven by international reporting obligations and are part of a strategy to rebrand the Gulf states’ images in line with global climate change and sustainability movements. Despite sizable climate pledges and large-scale projects, there is concern that neither the UAE nor any other Gulf nation is on track to meet self-declared clean energy and climate targets. While some experts have labeled these initiatives as greenwashing, others welcomed them as an important achievement of the climate and energy transition agenda. The latter believe that expertise in hydrocarbons and possible advantages in renewable energy make the Gulf nations potential drivers in promoting sustainability initiatives worldwide by integrating hydrocarbon-fired facilities with clean energy systems and diversifying the energy mix by integrating renewables, nuclear power, hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

The Gulf and Europe’s energy security

With new sources of energy discovered and the energy transition accelerating, limited energy resources will likely be less a source of conflict in the future. Changing energy trading dynamics and shifts in strategic relations between the world’s largest suppliers and consumers, however, may trigger conflicting dynamics and affect energy security.

The Russia-Ukraine war is among those major events that have altered global energy trading. It has been three years since the Russian invasion, which makes it possible to trace the impact of the conflict on energy security and assess shifts in trade dynamics. The war and the resulting European exodus from Russian oil and gas markets are incentivizing Russia to expand its export capacity to Asia, while European customers are showing a greater interest in Gulf energy resources. These developments present both opportunities and risks for broadening European Union-Gulf energy cooperation.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has led to dramatic spikes in oil and gas prices in Europe, some energy shortages and the urgent need to move away from dependence on Russian energy resources. To meet Russian fossil fuel shortfalls, the EU has turned to suppliers in the Middle East and North Africa. Several European ministers have recently conducted visits to Algeria, Azerbaijan, Egypt and Israel, with the aim of exploring new sources of natural gas. However, the expected increase in supply is not significant enough to make a substantial impact on the European energy market. Considering the Gulf region’s resource potential, it is not surprising that the EU attempted to embrace the Gulf states as key new energy partners.

A few months after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the European Commission announced the REPowerEU plan, intended to speed Europe’s transition away from fossil fuels, and especially from its dependence on Russia. The same day, the EU announced a significant strategic partnership with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states to enhance collaboration. While the document covers a wide range of areas for collaboration, including economic, security and institutional ties, the focus is clearly on energy.

European leaders’ visits to the Gulf hydrocarbon producers have, to a certain extent, been paying off. The Energy Deals Tracker listed several recent agreements between European states — including Austria, France, Germany and Italy — and Gulf energy-producing nations. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz toured the Gulf, which resulted in a long-term deal to import LNG from Qatar, and energy partnerships on collaboration in hydrogen development and energy efficiency initiatives. France signed a comprehensive strategic energy partnership with the UAE in 2022. Alongside LNG cooperation, Italian energy multinational Eni agreed to cooperate with Saudi Arabia on a wide range of sustainability initiatives. Most of these deals between EU and Gulf states are, for

now, short-term and focus on diversifying European oil and gas supplies.

His Excellency Jasem Mohamed Albudaiwi, secretary general of the GCC, repeatedly highlighted that the Gulf nations are reliable partners in ensuring energy security worldwide. With new developments unfolding, it is imperative for Europe to reevaluate and enhance its relationship with the Gulf. Manifold benefits make it a compelling proposition for all parties and give more impetus to the partnership. For Western nations, however, expanding and deepening ties with the Gulf energy suppliers come with obvious complications, not least of which is the continued use of fossil fuels, considering the climate crisis. Europeans risk replacing a geopolitically problematic dependency on Russia with a potentially problematic dependency on the Gulf, which is also grappling with widening and intensifying conflicts in the Middle East.

The Gulf is moving away from the decades-old, one-dimensional policy of aligning with the United States toward a multidimensional foreign policy. This change increases geopolitical uncertainty in the region, but Gulf leaders largely perceive it as necessary to exercise greater agency and pursue their own energy security priorities, and to provide security for energy and trade routes and contribute to the global energy transition. Gulf policymakers explain this policy orientation as a hedging strategy, through which they are trying to sustain relationships with all major (competing) powers. They want to keep all options open to offset multiple risks in the face of increasing geopolitical and economic uncertainty. With this strategic focus, Gulf leaders will be less likely to form alliances but will give preference to stronger partnerships with regional and global players. The Gulf states have, to a varying degree, built networks of partnerships involving China, the EU, India, Israel, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, the U.S., etc., in a bid to diversify their foreign relations and acquire greater autonomy. In pursuit of greater autonomy and geopolitical maneuverability, the Gulf nations’ pivot to Asia has accelerated significantly over the past two decades. Despite Europe’s interest and evident energy demand, Gulf suppliers’ ability to redirect oil and gas in significant quantities will be constrained by their long-term strategic orientation toward Asia.

Plans have already been set in motion to increase oil and LNG exports to Europe, but this should not be taken for granted. Since the mid-2000s, the global energy trade in oil and gas has shifted from the Atlantic basin to the Indo-Pacific, with Asian economies increasing demand for energy. The Indo-Pacific region is projected to dominate increases in global energy demand by 2040, with China, India and Southeast Asia accounting for two-thirds of that growth. Efforts to shift from fossil fuel-based economies to ones driven by sustainable energy will not end dependence on oil and gas in that part of the world. Most of the Gulf’s oil and gas currently flows to Asia, where the UAE, Kuwait and Oman export 96%, 80% and 70% of their crude oil, respectively. As far as oil and gas are concerned, Asia will remain dependent on Gulf energy as other options do not seem promising at this point.

Even the Gulf suppliers’ new deals with European consumers are insignificant compared with their energy supply commitments to Asia. In 2022, Germany signed a 15-year deal with Qatar to import 2 million tons of LNG starting in 2026. Concurrently, Qatar signed two long-term gas supply deals with China in 2022 and 2023, each for 27-year periods, to deliver 8 million tons of LNG. Another Qatari agreement with Bangladesh is expected to increase export capacity to 3.3 million tons of LNG. The amount of gas to be imported by Germany from Qatar is about 17 times less than that supplied by Russia before the war. The relatively small size of the contract underlines Germany’s desire to meet its carbon-emission targets, including reaching carbon neutrality by 2045, four years after the Qatar contract is due to end. It also means that Europe will remain a limited market for Gulf oil and gas.

While some spare oil production capacity is available in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the same cannot be said for natural gas, at least not in the short run. Expanding gas supply capability from the Gulf to alleviate a potential shortage in Europe will take time. Top LNG exporter Qatar is locked into long-term contracts, mostly with Asia, and will not have surplus gas for export at least until 2026. Even with the global energy transition accelerating, the demand for gas will paradoxically continue to increase across all continents, making it critical for future global energy security and the target of intense competition. Natural gas is still a fossil fuel but produces 50% less carbon dioxide emissions for power generation than coal and provides backup power supply for renewables. The Gulf is home to 25% of global gas reserves, yet contributes just slightly more than 8% of global supply, which leaves a sizable margin for future development. However, the near doubling of gas production by 2030 to meet growing demand could be challenging even for an LNG giant like Qatar.

Currently, Gulf nations are neither allies nor critical energy suppliers to Europe. Cooperation between the Gulf and Europe represents a good test case for both of their energy security strategies. Gulf monarchies are supporting Europe’s efforts to decrease its dependence on Russian energy. To enhance their short-term energy security, European nations must engage with the world’s richest oil and gas region, which may affect both parties’ global climate mitigation efforts. The Gulf region’s domestic carbon dioxide emissions account for merely 2.4% of the global total, but supplying the world with large quantities of oil and gas makes the region a huge exporter of carbon dioxide emissions. Thus, Europe’s attempt to strengthen ties with Gulf exporters may send mixed signals about the former’s commitment to decarbonization.

However, the greatest barriers to expanding energy relations between European and Gulf states are not technical or economic, but political and security-related. Until now, European states’ foreign energy policies toward the Gulf have been primarily driven by ad hoc and short-term reactions to geopolitical events, not by far-reaching and comprehensive strategies. Middle East oil and gas suppliers, including the Gulf exporters, have not been considered entirely reliable partners by Europe. Thus, unlike Asian importers, European customers were reluctant to pursue long-term deals. Now, not only do the Gulf nations’ strategic, long-term priorities lie with Asia, but oil and gas alliances with Russia complicate the Europeanization of their foreign energy policies. The Gas Exporting Countries Forum, which is headquartered in Doha, includes Russia. And three of the Gulf states are OPEC members, while OPEC+ includes Bahrain and Oman, along with Russia. Gulf-Russia geopolitical and geoeconomic ties have not always been linear, but they have often remained on the same side when energy interests are concerned.

The global energy supply has so far remained uninterrupted. However, a prolonged conflict in the Middle East would mean more disruptive attacks on energy and transport infrastructure, whether by Iran’s naval forces, its proxies or other state and nonstate actors. The security of maritime choke points, such as the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal, is more fragile than ever. Altogether, around 25% of crude cargoes and 20% of LNG cargoes pass through the Strait of Hormuz. The Iranian navy periodically attacks or seizes commercial ships and oil tankers in the Arabian Gulf, while Iran-aligned militias attack Gulf energy production facilities. Rockets launched on Saudi Aramco facilities in 2019 and ADNOC facilities in 2022 are examples of such attacks. Iranian forces have also recently seized European tankers off Oman’s coast. The conflict between Israel and Hamas and the exchange of missile attacks between Israel and Iran have further escalated insecurity in the region. These threats not only drive up the time, but also the costs of shipping oil and LNG. Strengthening energy ties with the Gulf suppliers will force Europe to be involved in the region’s highly complex and risky geopolitics. Already occupied with the Russia-Ukraine war, European states would want to avoid even indirect involvement in the region’s conflictual dynamics.

If Europe has learned anything from the repercussions of Russia’s aggression, it is undoubtedly that excessive dependence on energy sourced from a single country is risky. Although the U.S. has met Europe’s immediate supply needs since the outbreak of the war, and they are part of a broader geopolitical, security and economic alliance, it is still dependence on a single supplier. In 2023, the U.S. exported more than 90 million tons of LNG (which was more than Qatar or Australia), up to 70% of which went to Europe. Since 2022, the U.S. has supplied Europe three times as much LNG as the next largest supplier.

Europe’s safest source of energy is what it produces itself. However, it has limited capability to meet its energy needs from domestic sources alone, particularly for oil and gas. Europe’s energy import diversification efforts and the Gulf suppliers’ interests in expanding energy partnerships present opportunities for both sides, but it is unlikely that the Gulf will become a major supplier of oil and LNG and, by extension, a key guarantor of Europe’s energy security. The Gulf’s strategic interests lie with Asia and will remain so for the foreseeable future. That said, Gulf oil and gas producers are well positioned to become important energy suppliers to Europe, thus contributing to its energy import diversification. Expanding energy ties beyond oil and gas imports through collaboration on energy efficiency, renewable energy and hydrogen development can also build reliable, long-term partnerships between the Gulf and Europe.

The Gulf states do not always act on energy issues as a bloc. The EU member states’ energy strategies are not always aligned either. Thus, energy cooperation would largely have to be carried out from both sides on a country-by-country and case-by-case basis. Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are arguably among the Gulf countries that present more benefits than concerns for potential European partners. Human rights issues may place Kuwait, Oman and Qatar on a list of troublesome Gulf partners. In turn, Gulf exporters have a longer legacy of energy cooperation with some European nations than others. Thus, a more secure strategy for the Gulf exporters and European customers would be to consider energy and trade opportunities through both the GCC regional framework and bilateral formats outside the framework of a formal strategic partnership.

Comments are closed.