Transition to clean energy must clear economic and geopolitical hurdles

By Dr. Ana-Maria Boromisa, Institute for Development and International Relations, Croatia

The ongoing energy crisis is the first truly global one, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The crisis began in 2021, caused by factors including surging global demand for natural gas combined with inadequate gas reserves during the extraordinarily rapid economic rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising prices for carbon dioxide allowances under the European Union’s emission trading scheme. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting international sanctions imposed on Moscow — a major producer and exporter of oil and gas — escalated the crisis.

The crisis has highlighted the challenge of increasing short-term energy security while implementing a transition to green energy sources. This challenge is recognized within the Berlin Process, an intergovernmental cooperation platform among Western Balkan governments (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina [BiH], Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia), and EU governments and institutions. Berlin Process delegates adopted the “Declaration on Energy Security and Green Transition in the Western Balkans” in 2022.

A green transition requires decarbonization of energy systems. This could improve energy security by reducing reliance on imported fossil fuels, but it also creates challenges related to the development and use of renewable energy sources.

Considering the heavy reliance on fossil fuels in the region, Western Balkan countries adopted a fairly ambitious decarbonization agenda for the period up to 2030. Within the framework of the EU’s Energy Community, which was founded to “create an integrated energy market and foster the use of renewable energy, energy efficiency and decarbonization,” each country has made commitments that derive from its candidate status for EU membership. The United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Dubai in December 2023, resulted in a call for governments to transition away from fossil fuels and amplified the green transition challenge.

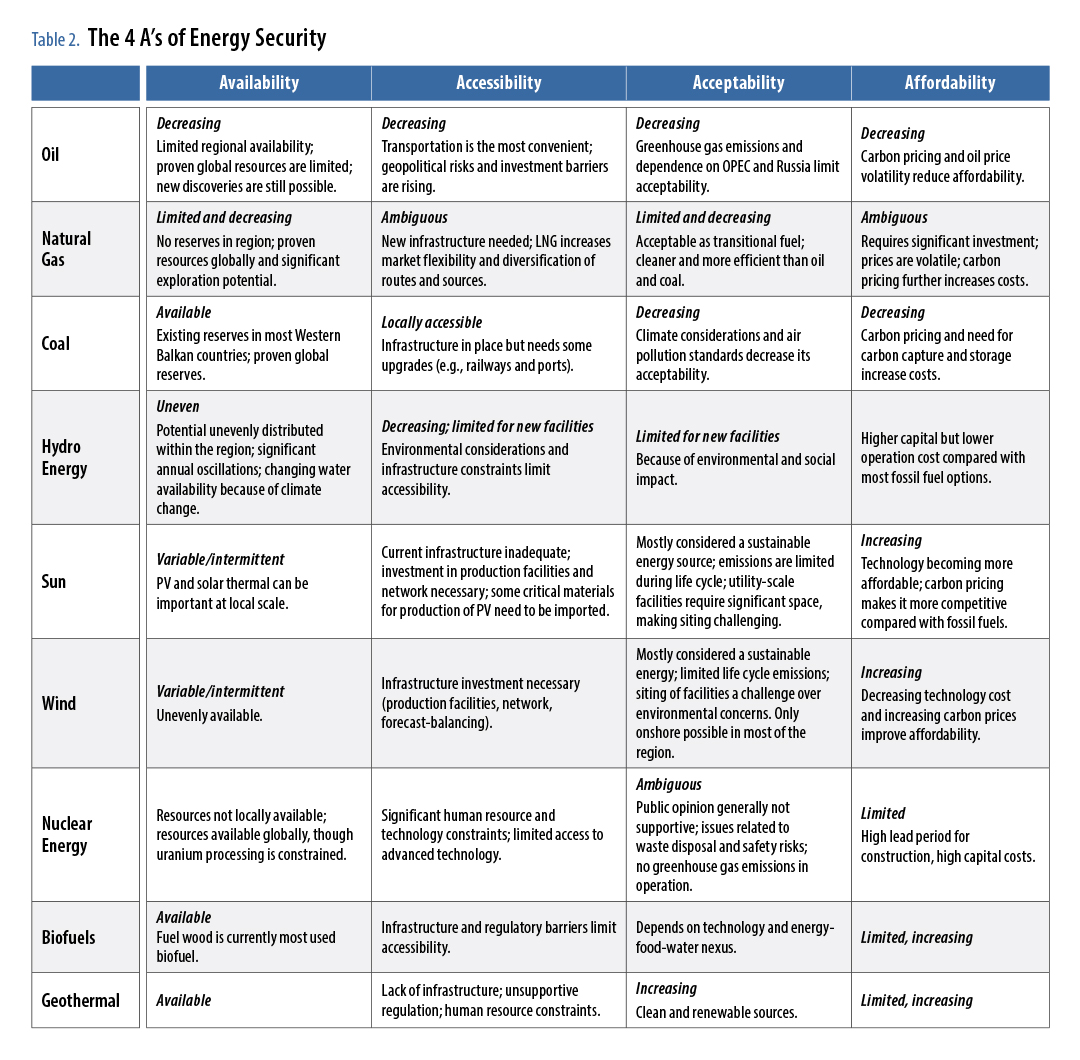

The IEA defines energy security as the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price. The key dimensions of energy security can be described as availability, accessibility, affordability and acceptability (the “4 A’s” of energy security). Having energy security means that the energy supply covers all economic and social needs. A comprehensive energy transition is required to align with climate goals while still meeting future energy needs.

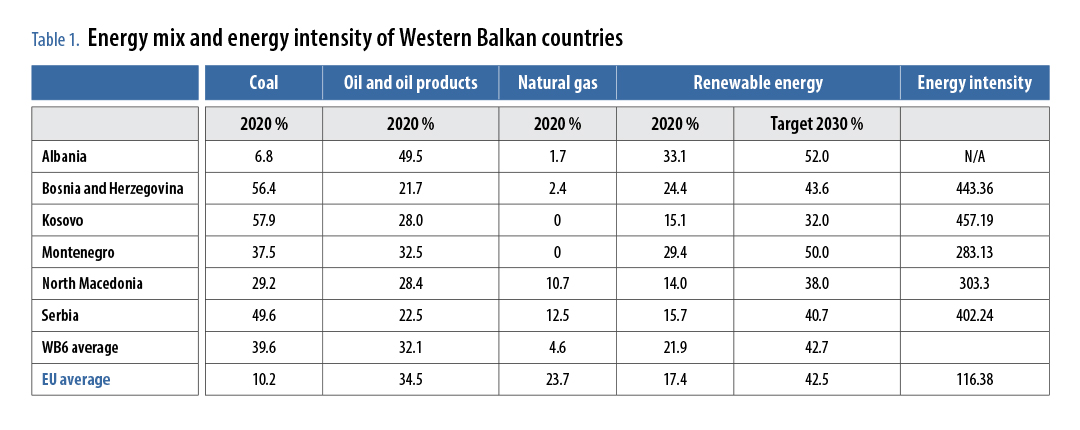

The high energy intensity and import dependency of Western Balkan economies make them vulnerable to increases in the price of energy imports. Regional economies rely heavily on fossil fuels (Table 1). Oil is used for transport and coal fuels power plants for electricity production. Only Albania and Serbia produce any oil. All the others have significant import dependency, exposing their markets to volatility in oil prices. From 2018 to 2020, only 3% of the region’s oil and oil product imports came from Russia, so the risk of supply disruption is smaller than for the EU.

Western Balkan economies are vulnerable to fluctuations in crude oil and oil derivative prices, but because gas has a limited share in the energy mix, they are not very vulnerable to gas price disruptions. The risk is mainly because the gas supply relies on a single source (Russia) and route.

In a globalized world, the impacts of crises come more rapidly and are more extensive. Weak and less-developed systems are less resilient. Where economic instability exists, crises are usually accompanied by political and geopolitical tensions. Thus, the global energy crisis has exacerbated existing energy security and green transition challenges faced by Western Balkan countries.

A diversified energy mix, lower import dependency and lower energy intensity generally contribute to the security of supply. Because of the high reliance on fossil fuels, significant import dependency and energy intensity, Western Balkan countries face significant energy security risks. For example, electricity in the Western Balkans is mostly produced from coal and hydroelectric energy. A significant share of the total electricity consumption in Albania (32%) and North Macedonia (24%) is imported, and Kosovo imports significant amounts of electricity in winter because of the widespread use of inefficient electric heating. Serbia had to increase electricity imports because of accidents at several thermal power plants combined with adverse meteorological conditions. On the other hand, domestic supply and demand nearly match in Montenegro, and BiH is a net exporter of electricity (27% of its production, but it’s mainly from coal). In addition, the energy intensity of the Western Balkans’ GDP (283-457 kilograms of oil equivalent, or kgoe, per 1,000 euros) is significantly higher than the EU’s energy intensity (116.38 kgoe/1,000 euros, see Table 1). This makes industries, especially energy-intensive industries such as aluminium, steel and fertilizer (25.6% in BiH and 24.2% in Serbia), more vulnerable to volatile prices. As a result, Western Balkan economies are more vulnerable to external risks.

The energy crisis has led to an unprecedented surge in commodity and electricity prices in the Western Balkans, heightening uncertainty. The impact of volatile energy prices is reflected in increased transportation costs (oil and oil derivative prices) and commodity prices. Rising electricity prices have reduced the competitiveness of industries and increased energy poverty. There has been a profound impact on the affordability of energy security. In addition, rising prices constrain investment capacity in energy infrastructure, renewable energy and energy efficiency, thus increasing future supply risk.

Measures aimed at protecting energy-vulnerable groups and mitigating energy poverty have been introduced, but the scope and impact remain limited. For instance, in BiH, energy support measures for the poor focus solely on direct financial support for energy costs and only target the most vulnerable groups.

The current energy crisis and its impact on short-term energy security show that the relationship between the four dimensions of energy security (4 A’s) is complex. It depends on a number of factors, including the energy mix, regulation and market structure. Strengthening one energy security element can damage other elements and even reduce total energy security. Addressing energy security challenges requires comprehensive policies capable of balancing short- and long-term policy goals.

The main impacts on each dimension of energy security, for fossil (oil, gas, coal), renewable and nuclear energy are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, there are energy security risks for each energy source. The impact on energy security varies over time and depends on the energy mix. Generally, the energy security of fossil fuels is decreasing because of their climate impacts and also political risks related to suppliers (for oil) and transport routes (for gas). However, access to liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies can help reduce gas supply constraints posed by pipeline infrastructure.

Diversification and developing adequate energy storage have been priorities for increasing security of supply. These are challenging issues in the Western Balkans. For instance, Albania’s legislation on the minimum reserves of crude oil and petroleum products required for energy supply security is not consistent with EU laws and regulations. In addition, Albania lacks a central holding facility for its emergency oil reserves.

Natural gas makes up a considerably smaller share of the energy mix in the Western Balkans than it does in the EU (4.6% compared with 23.7%, Table 1). While Russia is the sole source of gas in the region, Western Balkan countries have limited vulnerability to Russian gas import disruptions. This is less true for Serbia and North Macedonia, whose reliance on Russian gas imports reached 12.5% and 10.7% respectively in 2020 (Table 1). Kosovo and Montenegro do not have a natural gas market, while Albania has only been connected to an international gas pipeline — the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) — since 2020. Albania intends to connect its Vlora thermal power plant through both a pipeline and an LNG terminal to improve energy security. Preliminary agreements for gas supply have been signed. However, plans for development of the gas infrastructure have raised concerns from civil society, in particular regarding the ecological protection of Vlora Bay.

In 2022, Serbia concluded a new three-year contract for Russian gas after the previous 10-year deal expired in 2021. The price increased almost 30% (from $270/1,000 cubic meters to $340-350/1,000 cubic meters), but is still significantly lower than market prices in Europe, which were around $900/1,000 cubic meters. In BiH, gas provides only 3% of the energy supply, but it is very vulnerable to disruption, coming from a single source (Russia) through a single pipeline. Each of the country’s two political entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska, has a long-term contract with Russian gas supplier Gazprom.

Regarding the accessibility of gas, the Federation entity has been slow to adopt the law and permitting procedures for the Southern Gas Interconnector project. This is one of the flagship projects of the EU’s Economic and Investment Plan. Its implementation is expected to strengthen the integration of the Western Balkans into the European gas market and increase supply security. At the same time, BiH is considering a new Eastern Gas Interconnector to be funded by Gazprom. This interconnector would diversify supply routes, but not sources, thus the impact on security of supply would be ambiguous.

Domestic coal is widely used in the region for electricity production. The exception is Albania, which relies primarily on hydropower. Extending the lifetime of current coal power plants or considering the construction of new ones has been the primary response to the energy crisis. BiH extended the lifetime of two coal power plants (Kakanj and Tuzla). North Macedonia and Kosovo announced that they will postpone plans to phase out coal-fired power plants over the next few years.

Extending the lifetime of power plants that rely on domestic lignite coal increases security of supply. However, combined with delays in phasing out coal subsidies and alignment with the EU Emissions Trading System, these measures undermine environmental and decarbonization commitments. Failing to consider the true greenhouse gas-emission costs incentivizes the use of outdated coal units and poses environmental and security risks.

There are no nuclear power plants in the Western Balkans and most countries in the region have not expressed any intention to build one. However, neither has any expressed opposition to the construction of such facilities. Because of barriers for the deployment of nuclear energy, such as insufficient know-how, and lacking financial resources and public acceptance, there is a stronger economic and strategic rationale to prioritize less capital-intensive and faster-to-adopt alternatives, such as wind and solar energy. Still, at the first nuclear energy summit of the International Atomic Energy Agency in March 2024, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić said that his country would change its laws banning the building of nuclear power plants.

Renewables’ share of the energy mix in the Western Balkans is relatively high (ranging from 14% in North Macedonia to 33.1% in Albania). Most renewable energy in the region comes from hydropower. Albania, which relies predominantly on hydropower for electricity production, positions itself as a regional renewable energy leader. However, hydropower production is vulnerable to climate change and price volatility. Albania is a net importer of electricity at a rate of 30% per year, as its domestic hydroelectricity production is not sufficient to cover its needs. In addition, the concession contracts for hydroelectric power plants are not sustainable. The small plants have a significant impact on biodiversity and local communities, notably in protected areas, where around 100 concessions/private investments are located. Civil society groups challenged plans for a hydropower plant in Skavicë, on the Drin River, during public consultations, questioning the regularity of concession processes, the validity of environmental impact assessments and lack of information on the resettlement plan.

Renewable energy generation from other sources, such as solar, wind, biomass (wood and wood waste, municipal solid waste, landfill gas and biogas, biofuels) and geothermal is in its infancy. Albania plans to use more photovoltaic (PV), or solar, and renewable energy from wind. The exploitation of its vast solar and wind resources would significantly improve Albania’s energy security and reduce its vulnerability to climate change impacts. Development of two solar photovoltaic farms, with a total installed capacity of 240 megawatts (140 MW in Karavasta and 100 MW in Spitalla), is ongoing.

There has been progress in implementing regulation that could support the economic and financial viability of renewable energy projects. In 2021, Albania launched an auction on wind farms, with an installed capacity of 10 MW to 75 MW. The first-phase contracts were awarded in June 2023, and in July 2023 three bidders were awarded a total of 222.5 MW in capacity. To accelerate renewable electricity production and facilitate the transition from hydropower to other renewables, more auctions should be conducted.

In 2023, Kosovo adopted an ambitious new energy strategy and had its first solar auction. There are plans to adopt a law on renewable energy sources. In BiH, introduction of the virtual power plant model in 2022 has enabled small-scale renewable energy sources to reach wholesale markets via aggregation. This incentivized renewable energy producers to step out of the support schemes (feed-in tariffs).

Investments in networks would make renewable energy more accessible. Introduction of carbon pricing would change relative prices of renewables compared with fossil fuels, reflecting the diminishing acceptability of fossil fuels and making them less affordable. Energy transition to renewable energy sources and climate policy is expected to improve energy security by increasing energy independence. But this requires addressing the intermittence of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, and the vulnerability of hydropower to climate change.

Current energy security challenges due to energy mix and import dependency can only partially explain policy choices and short-term energy security interventions. Some energy policy choices are influenced by foreign policy priorities, (geo)political context and attempts to balance relations with Russia, the EU and neighboring countries, a sometimes-delicate balancing act.

North Macedonia, whose sole gas supplier is Russia, fully aligns with the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy and participates in sanctions against Russia. On the other hand, Serbia and BiH have not participated in EU sanctions against Russia. While Serbia’s dependency on Russian gas imports is significant, the small share of gas in BiH’s energy mix does not explain such a reluctance.

In the Western Balkans, limited attention has been given to developing new technologies for renewables, energy efficiency and storage. The focus on crisis management has, at times, diverted attention from critical systemic reforms. Such reforms require addressing vulnerabilities within energy systems, stemming from underinvestment and inadequate regulation, and those beyond energy systems. In general, systemic vulnerabilities beyond energy systems are associated with economic fragility (low employment rate, outdated and inadequate infrastructure), political instability (weak rule of law, inefficient governance structures) and social tensions (ethnic tensions, poverty, inequality, brain drain). As a result, the energy security challenge in the Western Balkans extends beyond immediate financial constraints and beyond the energy sector.

The current focus is primarily on availability and affordability, while civil society and environmentalists emphasize environmental and climate challenges. Long-term energy security requires addressing decarbonization, transition to renewables, improving energy efficiency and dealing with the intermittency of renewables. Achieving security of affordable supply and reducing emissions are critical steps.

The energy crisis has intensified concerns about disruptions in supply chains, increases in commodity and electricity prices, and the impact on the most vulnerable citizens. Rising energy prices fuel overall inflation and hurt confidence, thus endangering investment capacity. The impact of the crisis on investment capacity negatively affects Western Balkan countries with speculative (higher-risk) credit ratings, creating a special challenge in financing energy transition mechanisms.

It is important that the immediate crisis response — dealing with oil and gas supply disruption risks and price volatilities — not harm the structural realignment of the energy system with climate goals. The goal is for the transition to facilitate development of an affordable and secure supply of decarbonized energy. This includes reducing emissions to “net zero” within a time frame that allows alignment with the targeted maximum increase in global temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The energy crisis can boost clean energy deployment and become a major game changer. However, inadequate short-term responses could lead to locking in fossil fuel usage and reduce capacity to invest in clean energy, thus endangering the achievement of longer-term emission goals. The green transition presents opportunities for economic growth, job creation and poverty alleviation. Prioritizing investments in clean energy can address energy poverty by providing affordable and reliable access to electricity, thereby improving living standards and promoting social equity.

On the other hand, lack of investment intensifies energy security risks and endangers the green transition. Renewable energy reduces the need for energy imports, which increases energy security. A transition to clean energy will bring major structural changes to the generation profile of electricity systems. This requires increasing system flexibility and resilience. However, in the Western Balkans, the expansion of variable renewable generation has been modest.

Transitioning away from coal while ensuring energy security poses a significant challenge. There is huge potential to increase the share of renewables (see Table 1). In December 2022, the Energy Community Ministerial Council adopted the 2030 climate and energy targets. These targets provide the foundation for energy transition and could support energy security by ensuring affordable domestic sources. Achieving the targets requires comprehensive policies, supportive regulatory frameworks, adequate market institutions and investment.

Western Balkan countries have, under the Energy Community Treaty, committed to improving their market regulation. Alignment with EU energy legislation should enable the integration of Western Balkan energy markets into the European energy market, including the carbon-offset market.

Comprehensive policies are yet to be developed. The Western Balkan countries’ Energy Community target commitments are not fully transposed into national plans. For instance, in mid-2023, Serbia published its draft National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), which should provide a road map for achieving the 2030 targets. But Serbia avoided clear commitments in its draft NECP regarding carbon pricing or ceasing coal-fueled energy production, and the energy efficiency and renewable energy targets included were less ambitious than those Serbia had agreed to at the 2022 Energy Community Ministerial Council.

EU legislation treats energy efficiency as an energy source. The Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action and the Energy Efficiency Directive established energy efficiency as a first principle. The principle requires that energy efficiency be recognized as a priority in investment decisions in all sectors (going beyond energy systems) and at all levels, including in the financial sector. The energy efficiency first principle aims to ensure that only necessary energy is produced, investments in stranded assets are avoided and that demand for energy is reduced and managed in a cost-effective way.

In implementing the energy efficiency first principle, there is potential to improve legislation related to:

- The energy efficiency obligation scheme

- Energy labeling

- Increasing the number of electric vehicles in national car fleets

- The minimum energy performance of buildings

- Energy efficiency measures related to purchasing by public authorities

Inadequate investment in diversifying energy sources, upgrading existing infrastructure and decarbonizing the energy sector exacerbates dependency on volatile fuel markets. This undermines current energy security and heightens energy security risks into the future. Outdated energy infrastructure hinders efficient energy distribution and supply, and the integration of renewable energy. Investment in modernized grids, interconnections and energy storage facilities is crucial for decarbonization.

Infrastructure investment (e.g., in storage capacity), regulation and addressing emerging issues, such as digitalization and cybercrime, are necessary for efficient emergency preparedness and response. The diffuse and decentralized nature of much renewable energy generation and decentralized trading raises the risk of cyberattacks, as the attack surface is higher than in a centralized system. In addition, clean energy technologies rely on metals and minerals that are in tight supply and whose production is dominated by just a few nations.

Conclusion

The countries in the Western Balkans have prioritized security of supply and affordability over other aspects of energy security. The focus on crisis management has, at times, diverted attention from critical systemic reforms. Environmental and climate concerns are gaining attention from civil society, but to a lesser extent from policymakers. This challenge is particularly relevant for regions heavily reliant on coal. Increasing energy security by investing in domestic, low-quality fossil fuels can impede the energy transition, and it conflicts with the Paris Agreement and efforts to reach net-zero emissions.

Increasing long-term energy security requires energy transition. Energy security is expected to suffer during the difficult energy transition from cheaper fossil fuels. However, climate policies can improve energy security by accelerating the replacement of fossil fuels with domestically produced renewable energy. Renewable energy is gaining importance in the big energy security picture. Formulating and implementing good policies to ensure reliable energy access during the transition is a challenge. Holistic solutions must be found to address governance, environmental and social issues.

Energy security strategies should include investment in infrastructure compatible with renewable energy sources and decarbonized (electricity-based) transportation. Expansion of renewable energy production capacities creates new risks to energy security, including potential import dependency for transition metals, necessitating import diversification for critical materials. The higher upfront costs of renewable energy are expected to be compensated by lower operating costs. Considering financial constraints and the weak credit ratings of Western Balkan countries, deployment of renewables will require implementing new financial models.

The intermittency of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, poses a challenge to ensuring an uninterrupted energy supply, a key aspect of energy security. Policies have significant impacts on availability, cost, reliability and the environmental impact of energy systems. Thus, transposition of EU laws and regulations should be customized with consideration for local contexts. Implementation of the energy transition faces two prominent challenges: financial and human. Financial resources are necessary to translate plans and programs into concrete actions/investments, while developing adequate administrative capacity requires adequate human resources.

Comments are closed.