Europe Works to Sever Reliance on Russian Gas

By Martin Vladimirov, Center for the Study of Democracy

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exposed Europe’s vulnerabilities in energy and climate security. The war exacerbated the crisis caused by the gas supply deficit on global markets and highlighted the excessive reliance of many European Union member states on Russian fossil fuel imports. Europe must improve its energy sector governance to decouple from the Kremlin’s malign economic and political influence.

European countries have been forced to rapidly replace Russian gas at a time when there are limited alternative supply options (mostly liquefied natural gas, or LNG, from the United States and increased pipeline imports from Algeria and Norway) sold on an overheated spot market. Although key natural gas consumers such as Germany and Italy have accelerated efforts to diversify and move fully away from Russian gas, for many other countries — mostly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) — natural gas import risks have remained high as dependence on Russia persists.

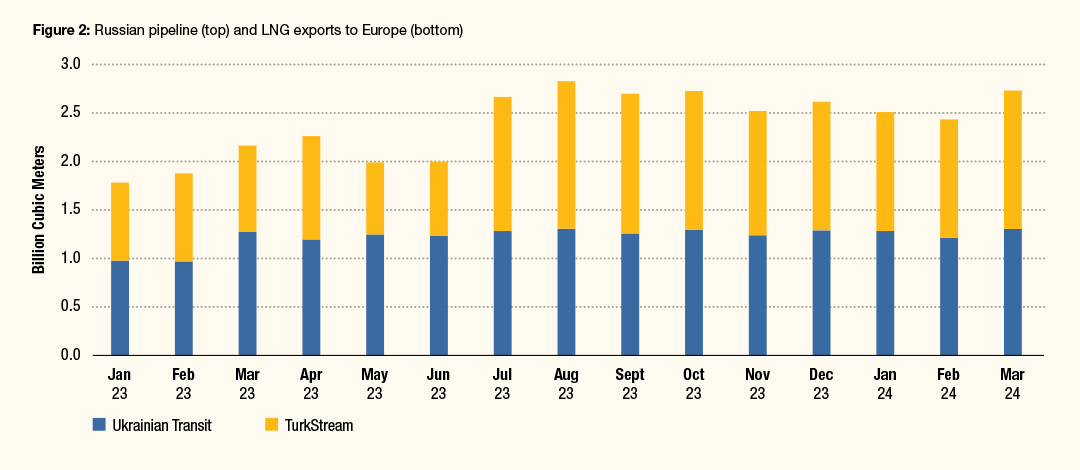

The flow of natural gas through TurkStream, a pipeline that delivers Russian gas to Greece, Hungary and the Western Balkans, remains unchanged in comparison with prewar levels, making it the largest source of Russian gas exports to Europe. Since its commissioning on January 1, 2021, until March 2024, TurkStream had transported 46 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian natural gas to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Greece, Hungary, North Macedonia and Serbia. At the same time, countries such as Austria, Slovakia and, indirectly, the Czech Republic continued buying Russian pipeline gas through Ukraine and have adhered to Russian state-controlled gas monopoly Gazprom’s proposed ruble-based payment scheme since April 2022 (Figures 1 and 2).

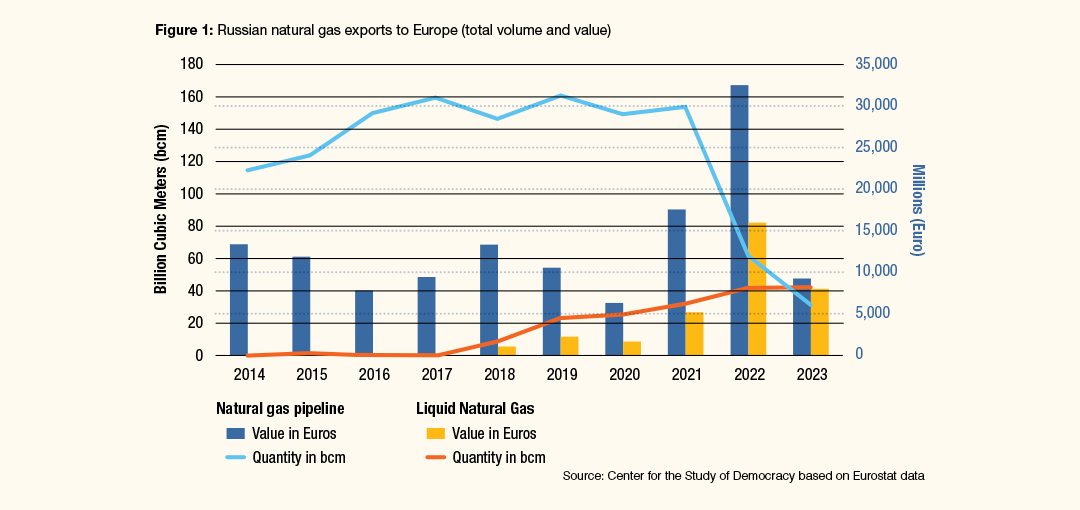

In 2022, Russian pipeline exports to Europe fell by 62% compared with 2021, but Russia received 13.8 billion euros more in revenues. In addition, Russia has been steadily increasing its LNG exports to the EU by investing heavily in LNG export infrastructure. In 2022, Russian LNG sales had the largest year-on-year increase (30%) in volume, leading to a 209% increase in revenues (about 16 billion euros) as a result of high prices in Europe.

In 2023, the phaseout of Russian gas imports to Europe finally started biting at the Kremlin’s revenues, which fell by close to two-thirds. Yet, Russia still sold more than 73 bcm of LNG and pipeline gas, raking in 17.3 billion euros. For all the hype about Europe successfully cutting its gas dependence, Russia still supplies 15% of total EU gas imports — closely trailing the U.S. (19%) and slightly ahead of North Africa (14%).

In 2023, the phaseout of Russian gas imports to Europe finally started biting at the Kremlin’s revenues, which fell by close to two-thirds. Yet, Russia still sold more than 73 bcm of LNG and pipeline gas, raking in 17.3 billion euros. For all the hype about Europe successfully cutting its gas dependence, Russia still supplies 15% of total EU gas imports — closely trailing the U.S. (19%) and slightly ahead of North Africa (14%).

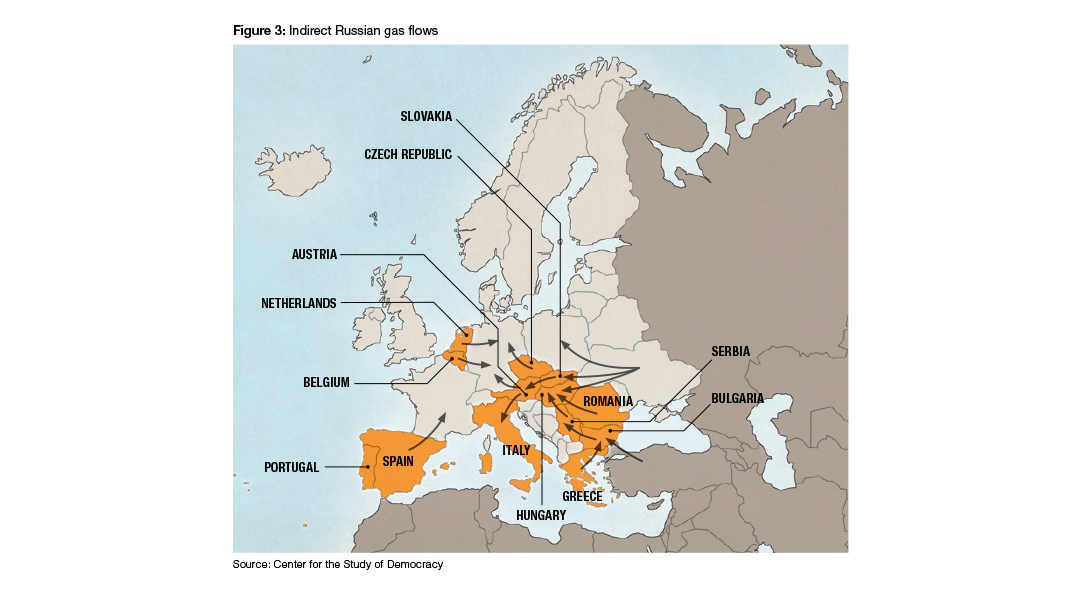

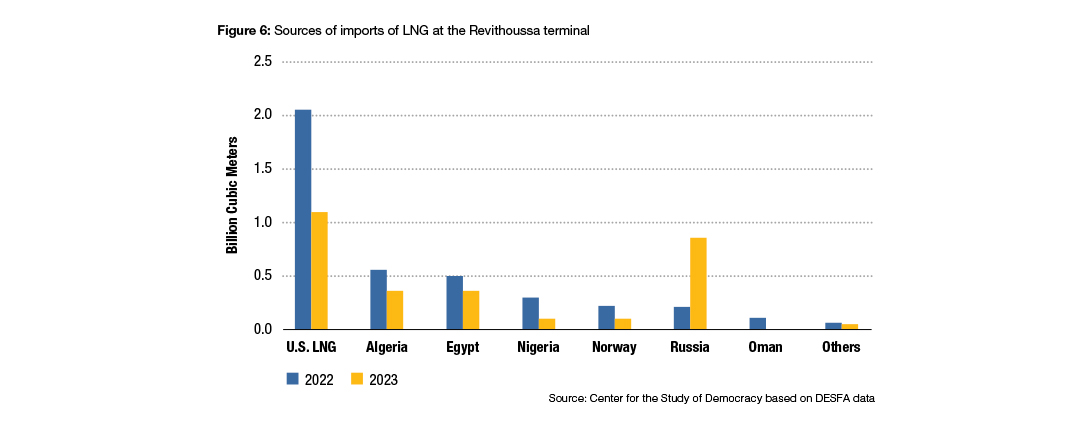

Among the EU countries that have increased Russian LNG imports are Belgium, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Some of the LNG is not consumed in the country of arrival but is shipped ahead to other markets, including those that suffered a direct Gazprom supply cut in 2022. The goal is to make the ultimate ownership of the natural gas untraceable (Figure 3).

Three examples clearly stand out. Bulgaria and Greece have been buying Russian LNG since 2022, although the former stopped buying Russian pipeline gas directly in April 2022, and the latter cut pipeline gas imports by 20%. Greek traders increased Russian LNG imports by 400% in 2023, widening the overall Greek dependence on Russian natural gas to 47%. Much of this Russian LNG was indirectly imported by Bulgaria, though initially destined for Greek companies that have long-term agreements with Gazprom.

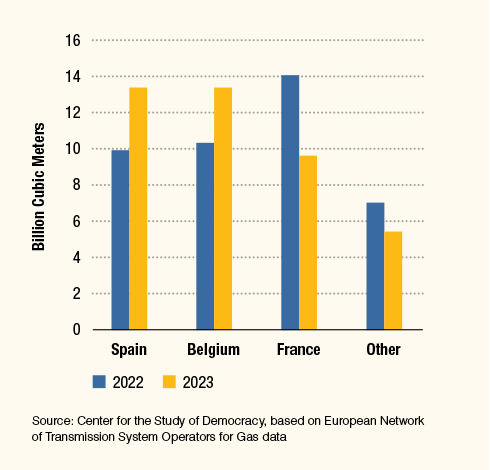

Similarly, Belgium has significantly increased its LNG imports since February 2022 to meet not only its own demand, but also that of Germany, the EU’s largest economy. In 2023, Belgium’s purchases of Russian LNG jumped by 30% to about 13.4 bcm, the bulk of which has been reexported to Germany, which receives around a quarter of its pipeline imports from Belgium. France and the Netherlands, which jointly imported another 11.6 bcm of Russian LNG, make up another 25% of German gas imports via pipeline.

Finally, Portugal and Spain became the biggest re-exporters of Russian LNG in Europe in 2023, buying more than 14 bcm and sending more than 50% of that volume east to France, Italy, Switzerland and others. Spain has become a hub for shipments of Russian LNG, enabled by trading companies that have had close ties to Russia, including MET Group and Gunvor.

Exporting gas via intermediaries has become a strategic Russian objective. The Kremlin aims to not only obfuscate ownership of the natural gas entering the European market, but also to preempt a potential full EU ban on such imports. The European Commission has advised member states to stop buying Russian gas by 2027, in line with the end of the long-term supply contracts of most of Gazprom’s European clients. Yet, this diversification effort could remain only on paper if Russian gas exporters can reroute their sales and expand their network of third-party companies ready to benefit from the premium profits they get for trading cheaper Russian gas.

Still in the Russian Gas Grip

In the absence of sanctions on gas, Russian supply continues to flow through the European pipeline system, albeit at lower rates. CEE countries have remained largely dependent on Russian gas imports. The main recipients of Russian pipeline gas have been Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Serbia and Slovakia. Slovakia, in particular, has become a distribution hub for Russian gas in Central Europe, acting as a transit country from the Ukrainian gas system for onward flows to Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary and Italy. In fact, Austria increased its dependence on Russian gas to 98% (up from 80% before the war), reversing the initial decision from the fall of 2022 to reduce gas imports from Russia. The major Austrian oil company, OMV, has a long-term supply contract with Gazprom that ends in 2040. However, that deal is now in doubt. Gazprom stopped supplies to OMV on November 16, 2024, when the Vienna-based utility said it would stop gas payments after winning an arbitration award connected to a previous price dispute. The company has discussed alternative supply options — including buying gas from Norway and from Azerbaijan (via Turkey) — but a structural change in Austria’s gas policy has been constantly delayed.

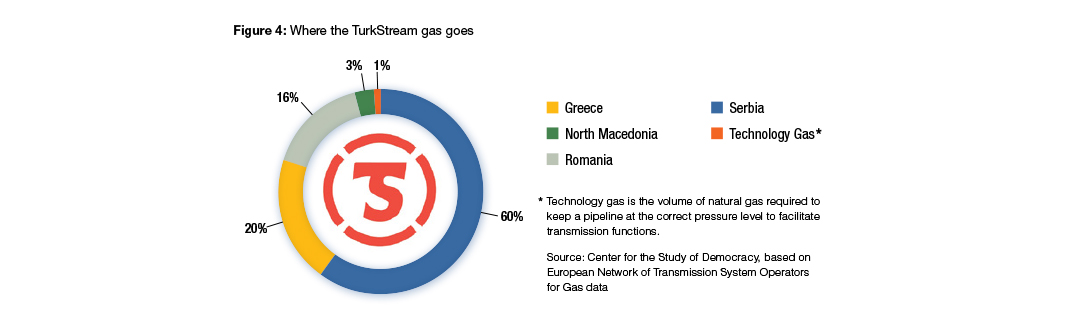

Hungary followed by expanding its natural gas imports from Gazprom under a 15-year supply contract signed in 2021 for 4.5 bcm/year. In 2023, Hungary expanded imports from Russia by at least another 1.5 bcm, with 75% of the volume transported via TurkStream (Figure 4).

In Southeast Europe, almost three years after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Gazprom is still king albeit with diminished power. The Russian company has effectively utilized TurkStream and legacy contractual arrangements for the booking of capacity on the Trans-Balkan Pipeline until 2030 to reduce the entry of gas from alternative sources.

Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (buying a total of about 3.1 bcm/year) receive 100% of their natural gas needs from Russia via TurkStream. In fact, 61% of transit volumes through the European extension of the pipeline are destined for the Western Balkans and Hungary. Another 20%, or about 2.7 bcm in 2023, is shipped to Greece and 16% to Romania, covering most of the natural gas consumption of Moldova and some 10% of Romania’s own gas supply. Additionally, less than 3% of the gas is delivered to North Macedonia.

New Outlets for Russian Gas Exports to Europe

As a result of the January 1, 2025, halt of Russian gas transit through Ukraine, Moscow could try to ship some of that roughly 14.5 bcm/year volume via TurkStream. Under the transit agreement between Gazprom and the Bulgarian gas transmission system operator, Bulgartransgaz, the Russian company can book up to 90% of the entry point to the Bulgarian gas network from TurkStream at Strandzha-2. Currently, Gazprom has been using some 75% of the available capacity, which means that it can increase distribution through TurkStream by 2.5 bcm/year.

The other rerouting option for Gazprom is to take advantage of the agreement signed between Bulgartransgaz and the Turkish state-owned gas monopoly, Botas, in January 2023, allowing the latter to use the entry capacity at Strandzha-1 (the old Trans-Balkan Pipeline cross-border point between Bulgaria and Turkey) in reverse mode. The deal allows the Turkish transmission system to transfer up to 1.9 bcm/year of gas to Bulgaria and opens access for Bulgargaz, the largest state-owned gas supplier in Bulgaria, to Turkish LNG terminals and storage facilities. If Bulgargaz does not use the booked capacity on the Bulgarian entry point for the import of gas from Turkey, the tripartite contract in effect allows Botas to sell some 3.65 bcm/year of gas to the Bulgarian and broader SEE markets. Since according to the Turkish gas law, natural gas entering Turkey automatically is owned by Botas, the Turkish company could resell surplus Russian gas volumes as nominally Turkish gas to the SEE market. This is consistent with announcements in late 2023 by senior officials in the Russian and Turkish governments that Gazprom and Botas are working on a concept for a natural gas hub in Turkey that will serve to replace Gazprom’s lost sales to Europe.

Considering that Gazprom uses only two-thirds of the available capacity of the two pipelines linking Russia and Turkey directly via the Black Sea — Blue Stream and TurkStream — the Russian firm could potentially expand sales to Turkey by 8 to 10 bcm/year. To resell these volumes on to the European market, Botas has been considering the use of the cross-border points with Bulgaria, where it can export roughly 6 bcm/year, and the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) reaching the border with Greece, connecting to the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) at the Kipoi border point, with another 2.5 bcm/year of available capacity. In a sign that the rerouting strategy is underway, Botas signed an agreement with the Hungarian company MVM to sell about 300 million cubic meters per year (mcm/year).

Ending Russian Pipeline Imports Post 2024

The SEE countries should be, and are, able to eliminate their dependence on Russian fossil fuel imports as a matter of national security. Doing so is the most direct path to halt the flow of funds from SEE to Russia’s war effort, and to counter its malign economic and political influence activities across the region. Hence, Russian natural gas transit through Ukraine having ended at the end of 2024, SEE countries have the unique opportunity to fully phase out Russian pipeline gas imports into Europe, which would require that Bulgaria, the entry point of the European extension of TurkStream, stops the Russian gas transit after the end of the winter heating season on May 1, 2025.

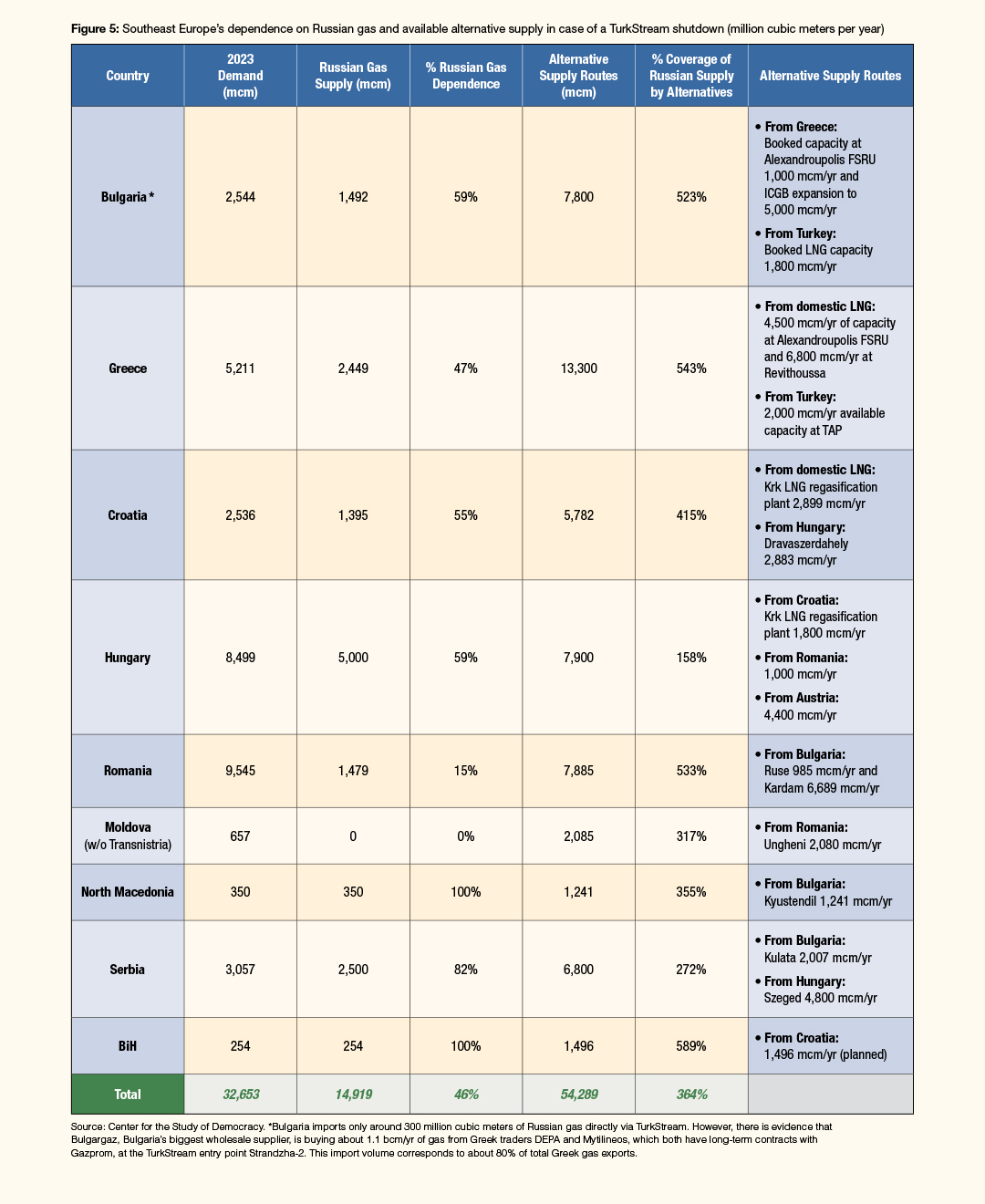

As a result, the SEE region will lose access to roughly half of its existing natural gas supply (Figure 5). Yet, there are no major security or supply risks from cutting Russian pipeline imports with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which receives 100% of its gas from Russia via the Serbian section of TurkStream, and which does not currently have easy access to an alternative gas supply (Figure 5).

The rest of the region will be able to leverage the significantly improved regional gas connectivity over the past seven years to fully replace reduced Russian gas volumes. Alternative gas delivery routes have the capacity to bring 3.5 times more gas than current Russian deliveries. This is possible because Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Romania and Serbia completed several strategic interconnector projects that have allowed reverse-flow gas deliveries on most SEE border points. Even more importantly, SEE countries have accelerated work on the now-empty Trans-Balkan Pipeline, which brought Russian gas to the SEE region via Ukraine until TurkStream was launched in 2021. The Trans-Balkan network could be used to ship LNG delivered to Greek and (in theory) Turkish regasification terminals to Central Europe, Moldova and Ukraine.

The launch of the Alexandroupolis Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU), which began commercial operations on October 1, 2024, will bring 5.5 bcm/year of additional LNG import capacity to the region. This means that Greece, which has another regasification plant in Revithoussa near Athens, would be able to import 12.3 bcm/year of gas from the global market, or around 79% of what is currently imported from Russia to the entire SEE region. Greece can, hence, fully replace its own Russian gas supplies, currently at close to 2.5 bcm/year. Greece also has a long-term supply contract with SOCAR for 1 bcm/year delivered from Turkey via the TANAP-TAP connection at the Kipoi entry point. There, Greece could potentially import another 2 bcm/year of Azeri gas or LNG delivered at Turkish terminals.

The Greek LNG regasification facilities can also fully replace Russian gas imports to Bulgaria. Bulgargaz already has 1 bcm/year of booked capacity at Alexandroupolis, which can be shipped via the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (ICGB), which is also delivering 1 bcm/year of contracted Azeri pipeline gas to the Bulgarian market. The interconnector’s total capacity is currently 3 bcm/year but will likely increase to 5 bcm/year in 2025, allowing for the redirecting of Alexandroupolis LNG deliveries to Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania and, potentially, to Hungary and Ukraine.

The latter will depend on how quickly the expansion of the reverse-flow capacities on the Trans-Balkan pipeline (expected to be doubled by the end of 2025) can be completed, bringing gas to Moldova and Ukraine, and also the interconnection point between Romania and Hungary. Bulgaria can also use the standing agreement with Botas until 2035 to import up to 1.9 bcm/year of LNG via Turkish terminals (Figure 6).

Romania, which is the biggest natural gas consumer in the region, satisfies more than 75% of its own demand with domestic production. However, it still bought around 1.5 bcm of Russian gas in 2023 via TurkStream. Although the Moldovan government in Chisinau said that it has stopped direct imports of Russian gas, TurkStream transit volumes to Romania indicate that this may not be the case, and that Moldova keeps buying Russian gas via intermediaries. In the medium term, Romania and Moldova could potentially fully phase out their dependence on Russian gas when the offshore Neptun gas field and its reserves of up to 100 bcm begin commercial gas extraction in 2027. Neptun will produce about 10 bcm/year, making Romania the largest EU gas producer and potentially a major exporter to Austria and Hungary via the planned Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria (BRUA) pipeline. The success of the project will depend on funding the key Podisor-Recas transmission link, which will bring the gas from the Black Sea to the Hungarian border. Until then, Romania and Moldova could replace Russian gas with more LNG imports from Greek and Turkish terminals.

The most vulnerable countries to the halt of TurkStream transit through Bulgaria are in the Western Balkans. While Serbia can cover 25% of its gas needs from domestic production and has access to supply from Hungary, and by extension from Western Europe via the Austrian Baumgarten gas hub, Bosnia and North Macedonia do not yet have an alternative supply route. The Krk LNG regasification terminal will play a key role in solving the last and possibly most complicated piece of the new gas supply-security puzzle — replacing Russian gas supply in Hungary. Gazprom sold about 5 bcm to Hungary in 2023, more than 75% via TurkStream. Phasing out that supply will require LNG imports at the Croatian island of Krk in the Adriatic Sea, which has only 2.9 bcm/year of regasification capacity, and would likely be used to cover the 1.4 bcm of Russian gas that Croatia buys. The rest could potentially go to Bosnia and Hungary, but this would not be enough to cover the shortfall.

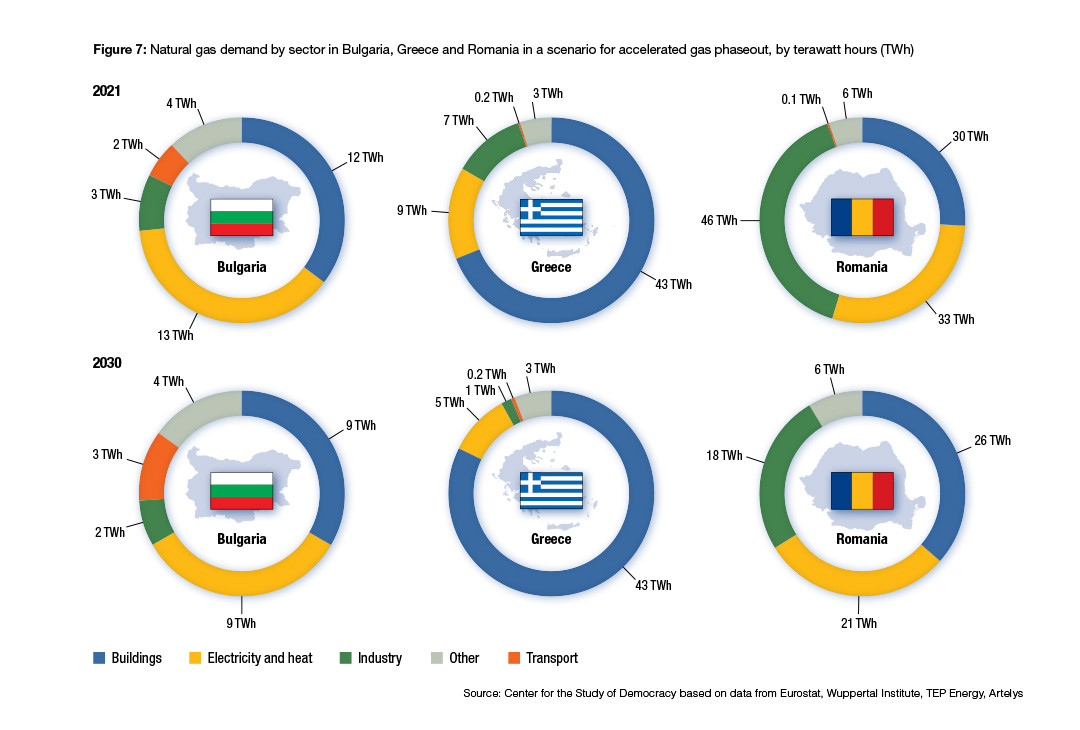

Phasing Out Natural Gas

Implementing ambitious decarbonization policies to reduce natural gas demand can substantially ease the phaseout of Russian gas in SEE. Promoting energy efficiency and electrification across different sectors, alongside encouraging biomass co-firing in district heating and for high-temperature industrial processes such as chemical production, could effectively mitigate the security risks of natural gas imports. An accelerated gas phaseout strategy could reduce gas demand by one-third across the region by 2030. The potential for reduced demand varies significantly among countries because of the differing roles of natural gas in their respective energy mixes.

Maximizing the potential to reduce natural gas consumption could transform Romania, for example, into a net exporter without requiring additional investments in gas production. For Bulgaria and Greece, while lowering natural gas demand may not eliminate import dependence, it would significantly reduce import volume. This reduction would greatly facilitate supply diversification without the need for additional infrastructure investments or the initiation of new long-term supply contracts. Signing such deals is challenging given the current tight global market, with fierce competition from larger consumers in Europe such as Germany and Italy, as well as from China. Therefore, SEE countries seeking new supply contracts may face difficulties in securing favorable pricing offers (Figure 7).

Power Sector

The pivotal factor determining the success of phasing out gas will be whether regional governments decide to build gas-fired power plants and how fast these plants would be replaced in the future. Greece is moving forward with five new gas-fired power plants that will collectively exceed 4 gigawatts in capacity and are scheduled to begin operations by 2026. Meanwhile, Romania has two active projects supported by EU financing. In Bulgaria, an initial plan to construct a gas-fired generation facility was scrapped. However, the risk of a policy reversal remains significant given the volatility in the national energy strategy.

Relying on natural gas as a transitional fuel to decarbonize the power sector is a short-sighted strategy that will lead to higher costs and stranded assets, along with increased energy and climate-security risks. The recent surge in power tariffs in Europe is largely attributed to soaring natural gas prices and inadequate low-carbon electricity sources. Expediting decarbonization necessitates a stronger focus on innovative technologies such as renewables, grid modernization and battery storage. These efforts should be prioritized post-2030.

Industry

The energy transition debate in Southeast Europe remains painfully shortsighted and ignores the critical issue of industrial decarbonization. The region requires a deep industrial transformation to secure its economic competitiveness. The low energy and material efficiency of national industries offers huge potential in terms of energy efficiency measures and for low-hanging-fruit innovation. Such measures can deliver considerable reductions in gas demand by 2030 and contribute to improving national energy and climate security. The surge in natural gas prices has already introduced a strong price incentive for industry players to invest in energy efficiency, and fuel and technology switching, which would contribute to significant gas savings across the region. Yet, more needs to be done. Instead, regional governments with short-term policy agendas chose to splash helicopter money at the sector through lavish energy subsidies without conditions.

Phasing natural gas out of industry requires a complex approach adapted to the different ways gas is used and with particular focus on the different temperatures required for various industrial processes. Typically, industrial heat demand is associated with high-temperature processes — greater than 1,000 degrees Celsius, which electrification is still unable to provide — such as cement and virgin steel production. However, direct electrification solutions are already competitive in low- and medium-temperature processes. The use of natural gas in these processes is inefficient and wastes the fuel’s potential. For low-temperature processes, other energy efficiency measures, including better insulation of industrial buildings and more efficient waste heat recovery also offer a strong potential for reducing overall energy demand and gas demand in particular. The deep decarbonization of industry requires a structural shift in all industrial production.

Buildings

The buildings category presents the greatest opportunity to reduce Southeast Europe’s natural gas demand by 2030, accounting for half of the total estimated gas savings. To fully realize this potential and achieve deep decarbonization, a comprehensive policy strategy that focuses on electrification, energy efficiency and addressing energy-poverty risks is essential.

Natural gas has seen significant uptake in the buildings category of Southeast Europe, particularly in Romania, where individual gas boilers have replaced district heating and biomass, making natural gas the dominant heating energy source. In contrast, Greece and Bulgaria are motivated to phase out natural gas in buildings because of high prices. Greece has a lower dependence on natural gas for heating, with less than 10% of demand met by gas, while Bulgaria has only 2.5% of households connected to the gas grid.

The buildings category in Southeast Europe suffers from poor energy efficiency because of an aging building stock that falls short of European energy performance standards. Overcoming these barriers could potentially reduce energy demand in the buildings category by 9% by 2030 compared with 2018 levels, leading to a 56% decrease in natural gas consumption within the sector, alongside increased electrification efforts.

Policy Action for Gas Phaseout and Supply Security

The EU should accelerate the implementation of REPowerEU targets by prioritizing the complete phaseout of Russian oil and gas supplies to Europe. By providing exceptions to the oil embargo and closing its eyes to increasing Russian LNG imports, the EU allows individual member states to profit from their special relationships with Russia, undermining European unity. The EU has a political obligation to accept a possible surge in energy prices and persuade member states to stop buying Russian gas even if this means short-term economic pain. To secure a 100% Russian gas phaseout in 2025, European governments would have to undertake a series of short- and long-term measures that overcome the congestion and contractual risks linked to the halt of TurkStream:

Improving Supply Security

- The EU should expand the scope of sanctions to include natural gas. Blocking Russian LNG exports to Europe is unlikely to hurt consumers as most of that gas goes to markets with many alternative suppliers (e.g., Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain), but stopping pipeline gas imports from Russia would be more challenging, especially when we consider the supply options of the Western Balkans and, to an extent, of Hungary. A sanctions regime with targeted derogations for the most vulnerable countries would be appropriate. Such exemptions should, however, be tied to a clear timeline for the phaseout of long-term natural gas contracts and specific steps for lowering overall demand.

- Full decoupling from Russia will not be possible without targeting the state capture networks that enable strategic partnerships between Russian and European energy companies. The EU’s economic security requires sophisticated mechanisms for screening and halting Russian strategic investments in Europe — both overt and covert — linked to state-owned companies and oligarchs close to the Kremlin. Such screening needs to be complemented by measures to ensure intrа-EU corporate-ownership transparency and strengthen the European antimoney-laundering infrastructure, as well as reducing the Kremlin’s hidden economic footprint in Europe.

- European countries should accelerate ending all long-term contracts with Gazprom. Several gas trading companies still have such deals with the Russian company, ending at the conclusion of 2025 (Serbia’s Srbijagas), in 2036 (Hungary’s MOL) and 2040 (Austria’s OMV). The simultaneous end of gas transit through Ukraine and through TurkStream should allow Gazprom’s clients to suspend or renegotiate their agreements.

- Ensure that Russia does not circumvent sanctions on Gazprom by passing its gas exports via intermediaries or by supplying the SEE region with LNG. There is a strong indication that Botas in Turkey is acting in cooperation with SOCAR as fronts for increased Russian gas sales to the SEE region.

- Complete gas diversification strategies by 2025-2026 by finalizing projects such as regional gas interconnectors, storage facilities and LNG regasification plants. It is crucial that Bulgaria accelerates the expansion of the Chiren underground gas storage facility. Greece does not have a gas storage facility, and for the regional market to function effectively, the country would need to either build one or use facilities in Bulgaria and Italy to manage the huge uptake of alternative supply. Greece is also planning a new LNG regasification facility near Kavala, and U.S. investors are mulling an LNG plant in Albania to bring U.S. supply directly to the Western Balkans.

- Gas imports at the LNG regasification terminals in Greece and Turkey will play a crucial role in maintaining security of supply. It is imperative that Bulgaria, Greece and Romania sign solidarity agreements, following the model of other EU members, to optimize the allocation of the limited alternative gas supplies entering the region. Without a nondiscriminatory interconnection agreement between Turkey and Bulgaria that opens the Turkish market to foreign gas traders, Turkey’s potential as a hub for secure and competitive gas supply would not be fulfilled.

- Avoid signing LNG supply agreements that last beyond five years, which is the standard duration in most of Europe. Priority should be given to new floating regasification terminals leased on a temporary basis rather than fixed facilities.

- The gas supply crisis should not be a justification to replace dependence on one gas supplier with another. Where possible, SEE countries should friendshore supply agreements, ensuring that they are based on beneficial commercial relationships that will facilitate the entry of constructive capital into the region.

- SEE countries should ensure physical and contractual reversibility of existing interconnection pipelines, including the Trans-Balkan transit pipeline, which Gazprom no longer uses. The pipeline should be able to transport expected surplus gas volumes of around 10 bcm in the next five years to Hungary, Moldova, Slovakia and Ukraine via the planned Vertical Gas Corridor, which would require additional expansion on the Greece-Bulgaria section and on the Bulgaria-Romania border.

- A common EU gas-purchasing mechanism should be introduced to secure stocks and achieve economies of scale in mobilizing alternative gas supplies. Russian and Azeri gas pipeline prices are cheaper than LNG imports on the spot market, which has been dissuading SEE gas companies from seeking alternatives. Attracting competitive supply at affordable prices would be more feasible if several SEE companies sign a joint contract with a major LNG supplier.

Gas Phaseout and Decarbonization

- The only sustainable long-term strategy for reducing security-of-supply risks is to phase out the use of natural gas. The untapped potential for energy efficiency remains a key supply-security risk. Cutting overall gas consumption will mean fewer fossil fuel imports, and therefore greater energy independence. SEE countries should undergo an accelerated energy efficiency investment strategy, focusing specifically on energy-poor households and deep renovation programs to reduce consumption faster than the current 2030 targets.

- Reduce the share of natural gas in the energy mix by replacing it with locally sourced renewable energy. This would not only limit exposure to Russian imports and geopolitical risks but also to the inherent price volatility of fossil fuels.

- Phasing out natural gas is possible if the region increases efforts to:

- Replace natural gas in heating with a heat-pump rollout strategy and electrification.

- Accelerate offshore wind and power-storage projects to replace natural gas power plants to cover peak demand.

- Avoid a natural gas lock-in by rejecting any new EU-financed natural gas transmission and gas-fired power plant projects unless they contribute to reducing short-term natural gas supply risks. Optimizing the use of existing gas infrastructure could limit the need for major expansion.

- Avoid adopting blue hydrogen as an alternative based on the increased use of natural gas, as well as the unnecessary construction of new or expansion of existing gas transmission networks repurposed for hydrogen transportation.

- A complete gas phaseout won’t be possible without major industrial decarbonization measures directed toward the electrification of production, especially in the most energy-intensive sectors, such as mining, metallurgy and cement.

Comments are closed.