The West African nation seeks to create a comprehensive counterterror strategy

Maj. Djomagne Didier Yves Bamouni

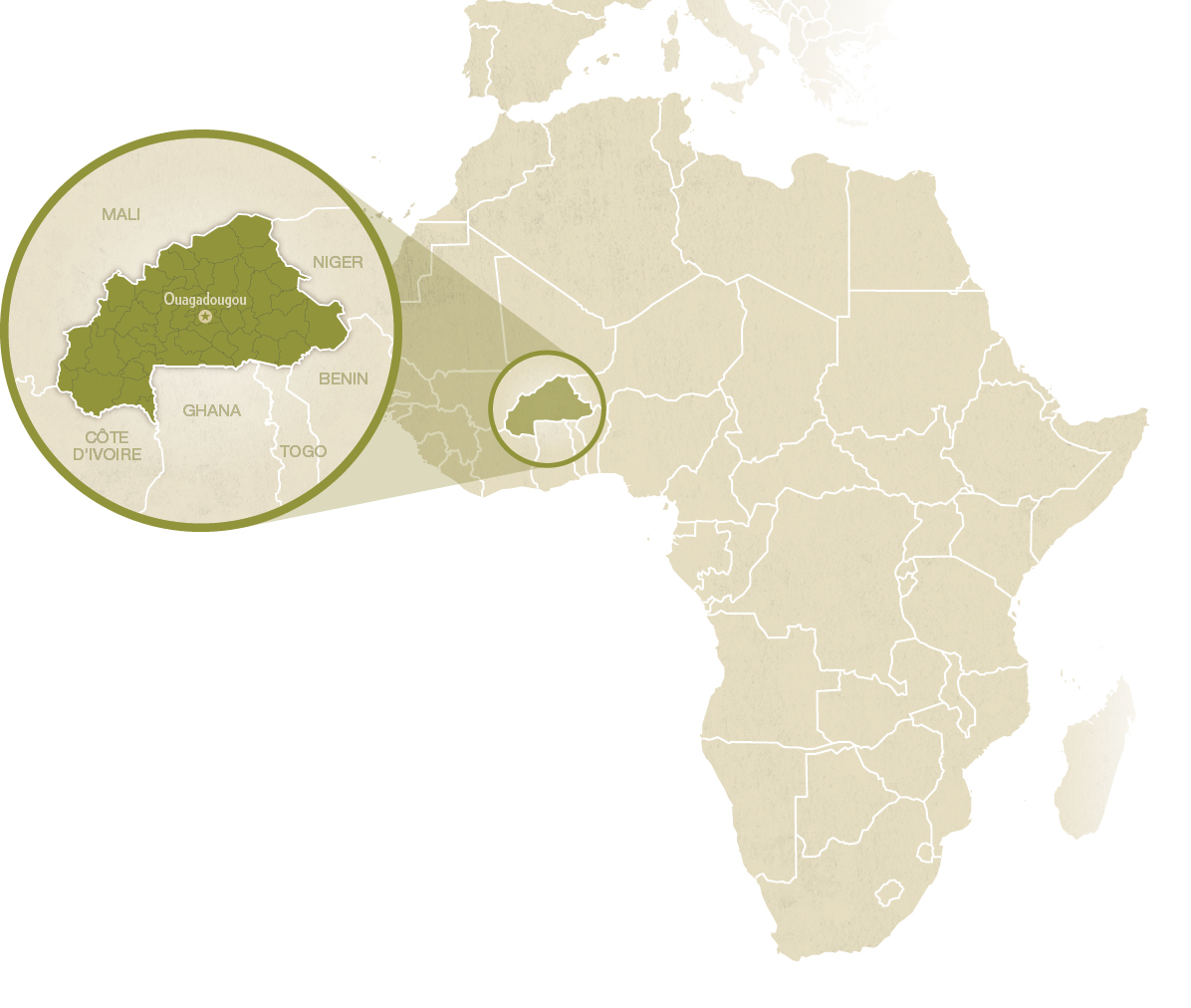

Terrorism and violent extremism have been prevalent in West Africa since the beginning of the Malian crisis in 2012. Among Sahelian countries such as Mali, Niger, Mauritania and Chad, Burkina Faso has remained safe from violent terrorism until recently — which may be attributed to its perceived role as a mediator.

Since 2015, terrorist groups such as al-Mourabitoun and the Macina Liberation Front, located in northern Mali, have started targeting Burkina Faso. The worst attack took place in the capital, Ouagadougou, on January 15, 2016, and claimed 33 people, including the three terrorists. Experts believe that more violent terrorist acts will take place in the region. Consequently, Burkina Faso must adapt its counterterror strategy, to be enforced by a joint counterterrorism agency.

Burkina Faso already uses a variety of kinetic and nonkinetic approaches when dealing with terrorism and violent extremism, employing different instruments of national power and social tools. But these approaches are not part of a comprehensive strategy.

Violent extremism in Burkina Faso

Terrorism and violent extremism are recent security challenges for Burkina Faso. In November 2014, the country went through a popular uprising that removed President Blaise Compaore from office. He was concurrently the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) mediator in the Mali crisis. The country was then ruled by a transitional body that also lost leverage in the political resolution of the Malian crisis.

Manifestations of terrorism in Burkina Faso have been threefold. First, the number of violent terrorist acts have increased in northern Mali — a development that is now impacting the security of Burkina Faso. In April 2015, a Romanian mining company worker was abducted in the northern part of the country, and a security officer was killed when trying to intervene. In August and October 2015, security outposts were hit in Oursi, in northern Burkina Faso, and Samorogouan, in the west. In January 2016, a restaurant and a hotel in Ouagadougou were stormed by terrorists. More recently, in September and October 2016, other security outposts were attacked in Koutougou, Intangom and Markoye in the north. The al-Mourabitoun group of Moktar Belmoktar and the Macina Liberation Front of Amadoun Kouffa — both affiliated with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) — are suspected to have conducted these attacks.

Manifestations of terrorism in Burkina Faso have been threefold. First, the number of violent terrorist acts have increased in northern Mali — a development that is now impacting the security of Burkina Faso. In April 2015, a Romanian mining company worker was abducted in the northern part of the country, and a security officer was killed when trying to intervene. In August and October 2015, security outposts were hit in Oursi, in northern Burkina Faso, and Samorogouan, in the west. In January 2016, a restaurant and a hotel in Ouagadougou were stormed by terrorists. More recently, in September and October 2016, other security outposts were attacked in Koutougou, Intangom and Markoye in the north. The al-Mourabitoun group of Moktar Belmoktar and the Macina Liberation Front of Amadoun Kouffa — both affiliated with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) — are suspected to have conducted these attacks.

Secondly, radicalization hotspots have been found in certain areas. For example, a little sect in Bobo Dioulasso has been practicing a religious doctrine similar to Salafism. And some Sunni mosques practice a strict Islam, including the rejection of Western culture. However, in both cases, they have not openly called for jihad. So far, one jihadist group has clearly emerged and carried out the attack at Samorogouan. The group is believed to include up to 30 former members of the Islamic police in Timbuktu during the occupation of North Mali by terrorist groups. The group is now dismantled with most of its leaders in custody in Mali and Burkina Faso. The results of a recent study were discussed in June 2016 in Ouagadougou by researchers, security practitioners and civil society. They all acknowledge the structural problems and enabling factors that prevail in Burkina Faso. This radicalization is Islamic and occurs in mosques and the countryside with the assistance of foreign predators who sometimes use money to attract poor people. Since 2013, 425 foreign predators have been registered by the Security Services. There are also reports of the preaching of extremist views in rural areas in the southern and eastern parts of the country. This threat should be taken seriously, considering that 60.5 percent of Burkina Faso’s population is Muslim.

Third, there is no evidence of mass recruiting of young Burkinabe fighters by jihadist groups. However, some known jihadist fighters bear names that are common in Burkina Faso. Mainly, they are young Burkinabe who have studied in Arab countries such as Egypt, Sudan and Syria. They return to Burkina Faso after completing their studies, but find few job opportunities, in part because the public administration is not prepared to employ Arab speakers since the official language is French. Recently, some of these foreign fighters were arrested by the Burkinabe security services while preparing an attack on Côte d’Ivoire soil. Boubacar Sawadogo, another Ansar al-Dine South leader, was arrested in May 2016 by Mali security services.

Counterterror Tools

Burkina Faso does not yet have a well-established and comprehensive strategy for countering violent extremism and fighting terrorism. However, it uses a variety of tools to protect the country. When confronted by the recent attack in Ouagadougou, these tools enabled a stronger security response.

At the diplomatic level, the country is part of the African Union and ECOWAS. Burkina Faso Armed Forces are part of the ECOWAS Standby Force, and multilateral exercises have been conducted under that heading. Additionally, security and military cooperation with neighboring countries is paramount and is specified in Burkina Faso’s defense policy. The country, therefore, has excellent security and military cooperation relationships with neighboring countries at both the strategic and local levels.

This strong security cooperation was demonstrated in the investigation of the terrorist attacks in Ouagadougou, Bamako in Mali, and Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire through efficient information sharing that led to the arrest of suspects in all three countries. This cooperation was recently strengthened with the emergence of the G5 Sahel Group — a political grouping of Sahelian countries that includes Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. This has allowed for improved information sharing and the creation of joint border operations. Moreover, Burkina Faso has increased security and military cooperation with strategic partners such as France, Taiwan and the United States. This cooperation includes new foreign bases, training, equipment programs and joint operations.

Huge strides have been taken in military and security measures against terrorism since the start of the Mali crisis. The Burkina Faso Army was part of the first African-led International Support Mission to Mali, which aimed to stop armed terrorist, criminal and insurgent groups in Mali and prevent the spread of these groups to southern countries. Currently, Burkina Faso is the largest troop contributor in Mali, with 1,742 troops deployed, excluding the 140 new Formed Police Unit personnel deployed in June 2016 in Gao. In addition, a counterterror task force was deployed in northern Burkina Faso, successfully deterring offensive action against the country and helping to manage a huge number of refugees — 33,000 have poured in from Mali. With the support of strategic partners, Burkina Faso has developed a number of special units within the Army, the gendarmerie and the police. They have improved their hostage rescue, neutralization of explosives and investigation skills. Police controls have also been increased in cities and on roads. As part of community policing, local security initiatives have emerged, including the development of local vigilance groups. These groups, composed of people of mixed ages, have helped provide early warning to the security forces.

Intelligence networks have effectively protected the country. This working information network has helped allied countries rescue hostages and prevent terrorist actions. The liberation of Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler in 2008 and Swiss missionary Beatrice Stockly in 2012 are examples. The intelligence network’s effectiveness was proven again in 2014 at the crash site of an Algerian airliner in northern Mali. The national intelligence structure consists of intelligence services within the Army, the gendarmerie and the police. In addition, a Homeland Intelligence Coordination Center was created in 2011 with the objective of merging internal intelligence, allowing the ministry of security to be more effective. External intelligence was directed by the office of the head of state. The entire intelligence structure was closely overseen by the office of the president. The president’s military chief of staff was in charge of oversight. However, the political instability in Burkina Faso that led to the departure of President Compaore negatively impacted this structure. To fill the gap and centralize intelligence cells, a National Intelligence Agency was recently created. The agency has recently become operational under its newly designated head.

At the legislative and judiciary levels, the 2009 anti-terrorism law was updated in December 2015 to reflect increasing threats. The new law broadened the definition of terrorist acts to include some criminal acts that intend to influence the government and create fear in the population, preparatory acts and activities that support terrorism. Other changes included the lengthening of detention periods, the use of special investigative techniques such as surveillance and the elimination of time restrictions for search operations in cases involving terrorism. A special anti-terrorism court was created in Ouagadougou, but it needs to be operationalized. As part of this process, representatives of the judiciary met in May 2016 to develop specialized anti-terrorism jurisdictions. Other legislative initiatives include the creation in December 2014 of the National Observatory of Religious Events. This body, composed of representatives of the government and the different religions, was designed to monitor religious discourses and to promote interreligious dialogue and tolerance.

The economy plays a vital role in countering violent extremism. The country’s political leadership announced it would like to distribute wealth more equally through development programs. One noteworthy initiative is the annual development and infrastructure program that coincides with the celebration of Independence Day on December 11. Started in 2008, it consists of the government acknowledging the needs of local communities. For example, the government will consult with the local population and implement a new development project to realize the community’s goals. This initiative has allowed the government to develop remote cities and thereby diminish local grievances. As of now, six cities have benefited. Other development projects include youth employment, farm production and empowering women.

The social background of the country plays the most important role in countering violent extremism — this needs to be recognized and strengthened. Burkina Faso enjoys a peaceful social environment driven by social cohesion and dialogue. Burkinabe don’t identify themselves through religion, race or color, but rather through ethnicity. Fortunately, many conflict resolution tools exist among ethnic groups. Two, among others, are joking relationships and the predominance of notables. This culture of joking allows two individuals or groups to engage in unusually free verbal or physical interactions. Notables are respected and wise people who traditionally wield large influence in society. Both of these tools can be used to reinforce national cohesion. Education needs to be updated to strengthen the national identity of “upright people,” to what it was during the revolutionary period. Burkina Faso actually means “country of upright people.”

The future

Burkina Faso shares borders with six nations, making cooperation key for its survival and for fighting terrorism. Military and security cooperation already exist but they need to be strengthened. In fact, the G5 Sahel initiative can be extended to other neighboring countries, including Senegal and Nigeria — the whole entity being the first line of defense against the spread of terrorism from north to south. Significant military and security improvements have taken place since the beginning of this initiative. Burkina Faso is more likely to plan and conduct joint operations in areas of interest and share information with other G5 countries. In this regard, the country has developed or resumed previous communications networks at strategic and tactical levels. Quarterly coordination meetings and chiefs of defense staff meetings are each held in rotating capital cities. And most important, G5 militaries now train with counterparts in other countries, building interoperability and trust. The contribution of strategic partners cannot be overlooked and needs to be reinforced as well.

Education programs should include violent extremism awareness programs and build a sense of human and Burkinabe values, such as uprightness, fighting corruption, hard work and tolerance, and promote Burkinabe history and culture. In that regard, Speaker of Parliament Dr. Salifou Diallo inaugurated the international conference on the prevention of violent extremism held by the West African Organization for Muslim Youth in Ouagadougou from August 16 to 18, 2016. He noted that education is a key to solving violent extremism. Working with families, especially mothers, has proven to be effective in many places and should be adopted in Burkina Faso. It strengthens family relationships and develops a sense of common responsibility. In short, mothers need to be aware of their roles in creating a better society where extremism cannot take root. The department of women’s promotion is ideal to run such a project. Development projects need to be reinforced as well. The existing initiative of celebrating Independence Day with development programs should be extended to remote localities after being completed in the 13 regional capitals.

Fighting terrorism and countering violent extremism in Burkina Faso require more than cooperation and strong social cohesion. It requires a unified purpose and a comprehensive action plan. Taking advantage of ongoing security and defense sector reforms, the comprehensive approach to fighting terrorism and countering violent extremism can be strengthened and adopted. This strategy should include establishment of a joint counterterrorism agency with stakeholders ranging from security practitioners to lawyers, civil society organizations, and religious and traditional leaders. This institution will help get government agencies and the population on board in the fight against terrorism and extremism. It will signal to the population the importance of this fight and reassure citizens that the government is taking action. This strategy needs to be publicized so that everyone is included and acknowledges the objectives and courses of action.

In conclusion, although Burkina Faso does not have a well-established and comprehensive strategy to fight terrorism and counter violent extremism, it does use a variety of instruments that have proven to be effective. However, certain areas need attention. The importance of cooperation is paramount, since terrorism recognizes no borders. Development programs should be widened, with more emphasis on the country’s youth, which constitute more than half of the population. To achieve long-term security, resilience should be built through strengthening Burkinabe social cohesion and national identity. This goal is difficult or impossible without a comprehensive strategy run by a joint counterterrorism agency.

Comments are closed.