Time for a new approach?

By Maj. Gen. Walter T. Lord, U.S. Army National Guard

Since 1995, NATO, the European Union and other international partners have been engaged in the Balkans — politically, diplomatically, economically and militarily — in varying degrees of intensity. The international community initiated its intervention to end a devastating conflict that accelerated the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia. That conflict, lasting from mid-1992 through the end of 1995, was merely the most recent chapter in a long history of conflict that has plagued the Balkan region, a product of its enduring position as an economic, religious and cultural crossroads.

By the end of the 15th century, the Ottoman Turks had gained control of a significant portion of the Balkans. From that point forward, the Balkan map was sporadically redrawn as one rising power after another seized control of territory and resources. Major powers such as the Ottoman, Habsburg and Austro-Hungarian empires, as well as regional forces, continually redefined Balkan borders for the next 500 years. In the wake of World War II, Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the son of a Croatian father and Slovenian mother, held together much of the Western Balkans in the form of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Regarded by many as a “benevolent dictator,” Tito was a popular figure at home and abroad because of his economic and diplomatic policies. He fostered a program of brotherhood and unity and suppressed nationalistic sentiments among the six Yugoslav “nations.” These policies and initiatives silenced nationalistic rhetoric and led to four decades of peaceful coexistence on the Balkan Peninsula. Tito died in 1980, and the brotherhood and unity he cultivated — or imposed, depending on one’s perspective — began to unravel almost immediately. His death created a leadership vacuum at the state level, setting in motion a chain of events that would result in the fracturing of the Yugoslav state, a political and diplomatic impasse, brutal armed conflict and horrific interethnic atrocities. In November and December of 1995, after 3 1/2 years of violence, the warring parties and members of the international community came together in Dayton, Ohio, in the United States to craft an agreement that would end the open hostilities. The General Framework Agreement for Peace, also known as the Dayton Agreement, required the introduction of international political control and the deployment of a robust NATO peacekeeping force.

REUTERS

Today, after 20 years of international involvement in the Balkans, the independent nations that once comprised the former Yugoslavia are experiencing varying levels of success in accomplishing their Euro-Atlantic integration goals. Most impressively, Croatia and Slovenia achieved membership in NATO and the EU. Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH), Macedonia and Montenegro all aspire to NATO and EU membership but have made vastly different levels of progress in reaching those aspirations — Montenegro completed the NATO accession process and should attain full Alliance membership, pending ratification by member nations. Serbia wants to join the EU, but does not — at least for now — want to join NATO, although it does participate in NATO partnership programs and is deepening its political dialogue and cooperation with the Alliance.

For the past 70 years, NATO has contributed significantly to its members’ security and stability and, by extension, to security and stability throughout Europe. The Western Balkan nations that aspire to NATO and EU membership state very clearly that they do so, in large part, to achieve the military, political and economic security that Euro-Atlantic integration provides. That integration, including advancement toward NATO membership, has progressed in fits and starts for a wide array of reasons, ranging from widespread government corruption to varying levels of public support for NATO to EU and/or NATO readiness to accept them as members.

For most of the past two decades, NATO has accepted intermittent success in the integration of Western Balkan aspirants. However, given the current security dynamics in Europe, it can no longer afford to do so. Stalled Euro-Atlantic integration in the Balkans opens the door to a multitude of threats that could once again unravel the relative stability of the past two decades. For example, the spread of Islamist extremism, Russian adventurism, renewed ethnic conflict, persistent weapons proliferation, widespread poverty and the growth of transnational organized crime are all possible if the Alliance fails to continue to invest its efforts in the region and to improve the return on that investment. The ingredients of all of those outcomes, including a troubling rise in nationalist rhetoric, exist in the Western Balkans right now.

Due to the historical significance and strategic location of the Balkan Peninsula, neither NATO nor the EU can afford another implosion there. Therefore, rather than turning away from the region, NATO must reorganize and refocus its engagement programs in the Western Balkans — specifically in BiH, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia — in order to standardize its approach while tailoring its activities in each nation. It must synchronize programs and provide a consistent and effective path to those nations aspiring to NATO membership or enhanced partnerships with the Alliance.

A brief history

On December 20, 1995, NATO’s Implementation Force (IFOR) deployed 60,000 troops to BiH to implement the military aspects of the Dayton Agreement. After one year on the ground, IFOR transitioned to the NATO Stabilization Force (SFOR). Over the next eight years, the Alliance would establish headquarters elements or deploy forces of varied strengths and with various missions to several former Yugoslav republics. Most of those elements were established to enforce the military aspects of the Dayton Agreement in BiH, or United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 in Kosovo, or to provide support to IFOR/SFOR and NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR). Eventually, with the exception of KFOR, they would all modify their missions to serve solely as NATO advisory and liaison offices in cooperation with their newly independent host nations. While not a complete shift from its original peacekeeping tasks, KFOR now also provides advice and assistance to the Kosovo Security Forces (KSF) — originally through a military-civil assistance division that merged with a NATO team that advises the Ministry of Defense and reports directly to NATO headquarters.

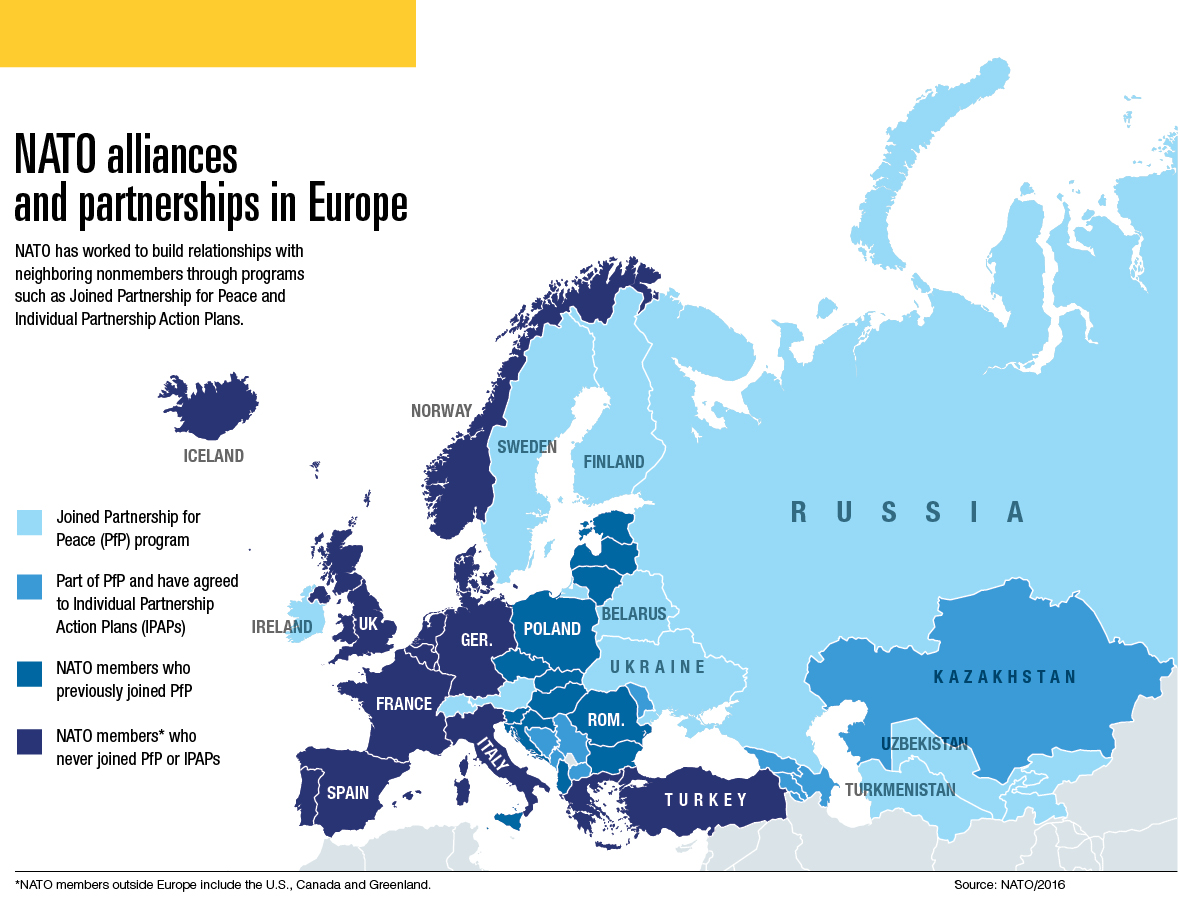

As NATO deployed to the former Yugoslavia for the first crisis response operation in its history, the Alliance’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) program was taking root in a number of former Soviet and former Yugoslav republics. According to NATO, “PfP is a program of practical bilateral cooperation between individual partner countries and NATO. It allows partners to build an individual relationship with NATO, choosing their own priorities for cooperation. Based on a commitment to the democratic principles that underpin the Alliance itself, the purpose of PfP is to increase stability, diminish threats to peace and build strengthened security relationships between individual partners and NATO, as well as among partner countries.” Several PfP nations would deploy peacekeepers to the Balkans alongside their NATO partners while a few of the newly independent Western Balkan nations began the process of joining PfP. Ultimately, 31 nations, including traditionally neutral ones, would participate in the program and 12 of those nations would progress from partner to member status within the Alliance.

REUTERS

While NATO engaged with its partners in its bilateral program, a number of member nations initiated enhanced bilateral military-to-military programs with select nations. The most robust of these was the United States European Command’s (EUCOM) Joint Contact Team Program (JCTP), hailed as EUCOM’s premier peacetime engagement program. At its peak, the program placed liaison teams in 17 partner countries to coordinate activities according to a work plan jointly crafted by the U.S. liaison team and host nation leaders. Eleven of those 17 JCTP partners would ultimately accede into the Alliance and would credit JCTP with helping to achieve their defense reform, military professionalism and NATO interoperability objectives.

With the success of these multilateral and bilateral programs and the stability and security they fostered, specifically in the former Yugoslavia, the need for NATO forces to enforce the peace was diminished significantly. By December 2004, NATO determined that implementation of the military aspects of the Dayton Agreement had progressed sufficiently that remaining tasks could be handed over to a European Union Force (EUFOR). Up to that point, SFOR had been gradually reduced from the original IFOR strength of 60,000 to a troop number of 7,000, a result of the security and stability that it had helped to take root, and the requirement for NATO to deploy forces to Afghanistan and Iraq. The SFOR mission was closed, and NATO turned over to EUFOR the task of continuing stabilization efforts and the accomplishment of residual (Dayton Agreement) tasks in BiH. This tactical role is distinct from the strategic advisory role that NATO now fulfills.

Advisory and liaison elements

With the reduced staffing and mission change, NATO established Headquarters Sarajevo (NHQSa) to advise BiH on defense and security sector reform and PfP matters. While it shares a legal mandate with EUFOR as joint successors to IFOR and SFOR, NHQSa has taken a supporting role to EUFOR in the execution of all residual military tasks. In addition to the traditional stabilization tasks, EUFOR has the lead for capacity building and training the Armed Forces of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Additionally, NATO has elements working day to day in two other former Yugoslav nations. Along with NHQSa, the Alliance has a NATO liaison office (NLO) in Skopje, Macedonia, and a military liaison office (MLO) in Belgrade, Serbia. Prior to Albania’s accession into the Alliance in 2009, NATO also had a headquarters in Tirana. That headquarters closed in June 2010. Finally, outside of the military chain of command and reporting directly to NATO Headquarters in Kosovo, a NATO advisory and liason team provides support to the KSF and its responsible ministry.

While EUFOR took the lead in BiH on the operational and tactical tasks of stabilization, capacity building and training, the establishment of NHQSa signaled a shift in NATO’s focus to the strategic task of defense and security sector reform, while assisting the Ministry of Defense and the Armed Forces with NATO PfP activities. In the wake of SFOR’s deactivation, NATO’s staffing levels in BiH were steadily reduced. NHQSa currently maintains a staff of 65 military and civilian personnel, which is sufficient to achieve strategic-level objectives and requirements to provide personnel, finance, contracting and communications support to EUFOR headquarters.

MLO Belgrade, established in December 2006, maintains a staff of 13 military and civilian personnel. According to the Joint Force Command, its primary mission is “to serve as a link with the military authorities of Serbia on the practical aspects of the implementation of the Transit Agreement between NATO and Serbia, which was signed in July 2005. The purpose of this Transit Agreement is to improve the logistical flow to and between NATO’s operations in the Western Balkans.” For the purposes of this examination, it is equally, if not more, important to consider the added missions that MLO Belgrade now executes:

Facilitating the implementation of Serbia’s PfP program with NATO and providing assistance to NATO’s public diplomacy activities in the region.

Supporting the Serbia/NATO Defense Reform Group, which was established to assist the Serbian authorities in reforming and modernizing Serbiaʼs Armed Forces and in building a modern, affordable and democratically controlled defense structure in Serbia.

So, as in the case of NHQSa’s replacement of IFOR/SFOR, a NATO presence fielded to perform operational-level tasks is now working, to a great extent, at the strategic level with its host nation partners. NLO Skopje (originally named NATO HQ Skopje) was established in April 2002 when NATO combined HQ, KFOR (Rear) and the HQ of NATO Operation Amber Fox, an alliance operation that protected international monitors representing the EU and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. NLO Skopje maintains a staff of 14 military and civilian personnel. The primary NLO Skopje mission, according to the Joint Force Command, is “to advise the Host Nation governmental authorities on defense aspects of Security Sector Reforms and NATO membership, in order to contribute to the country’s further Euro-Atlantic integration, and to provide support to NATO-led operations within the Balkans Joint Area of Operations.”

As outlined on the NLO’s home page, “NLO Skopje is a non-tactical mission and consists of military and civilian personnel, located in the host nation MoD. Generally speaking, we are involved in all levels of the national transformation processes. We have regular contact with the government leadership and other agencies (Ministries of Defense, Interior, Foreign Affairs, etc.), but mostly with the defense and military authorities. We have regular meetings with the heads of EU, USA and OSCE missions.” NLO Skopje is yet another NATO element created for a tactical/operational purpose but whose mission has evolved to one sitting firmly and indisputably in the strategic arena.

NHQSa, MLO Belgrade and NLO Skopje are all subordinate elements of NATO’s Joint Force Command, Naples (JFCNP). It is one of two standing operational joint force commands that are part of Allied Command Operations (ACO), one of NATO’s two strategic commands. JFCNP’s stated mission is “to prepare for, plan and conduct military operations in order to preserve the peace, security and territorial integrity of alliance member states and freedom of the seas and economic lifelines throughout SACEUR’s [Supreme Allied Commander Europe’s] Area of Responsibility (AOR) and beyond.”

Its role as an operational-level headquarters does not provide JFCNP with appropriate staffing, expertise or mission focus to offer effective oversight of subordinate headquarters and staffs that conduct defense reform and PfP activities at the strategic level. Although the three elements examined here have all been operating for a decade or more, JFCNP has only recently initiated collaboration and coordination among them. To its credit, JFCNP has created the Balkans Liaison Working Group with the stated purpose of sharing information and coordinating activities. Unfortunately, after several periodic one-day meetings, the group has produced no concrete results in terms of coordinated activities. This observation should not be viewed as a criticism of the JFCNP staff, but rather an indicator of the mismatch between the missions and areas of expertise of these liaison elements and their higher headquarters.

When NATO established its presence in Sarajevo, Belgrade and Skopje in the mid-1990s, each agency executed missions and performed tasks that were largely operational and/or tactical. It made sense, at that point, for them to be subordinate to an operational headquarters. It was also convenient because the NATO military operational structure had procedures in place to deploy them. Given their current missions, that command and control arrangement no longer makes sense. Commanders and liaison office chiefs who work with host nation counterparts at the strategic level should report to, and receive their guidance from, a strategic level headquarters.

Alternative approach

Given their evolution from tactical/operational missions to strategic ones, NHQSa, MLO Belgrade and NLO Skopje should be extracted from the JFCNP chain of command and placed within a bi-strategic command (Bi-SC) construct, reporting to both of NATO’s strategic commands, ACO and Allied Command Transformation (ACT). Such a command relationship is exactly the one that is in place for the Alliance’s Military Partnership Directorate (MPD).

“The MPD provides direction, control, coordination, support and assessment of military cooperation activities across the Alliance,” according to NATO. “It directs and oversees all non-NATO country involvement in military partnership programs, events and activities, and coordinates and implements NATO plans and programs in the area of partnership. The MPD is shared with ACO and is located at SHAPE [Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe] in Mons, Belgium, with a staff element at HQ Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT) in Norfolk, Virginia.”

A Bi-SC construct for the NATO liaison elements would enable direct access to one strategic command (ACO) responsible for alliance activities throughout Europe; access to a second strategic command (ACT) with objectives that include leading NATO military transformation and improving relationships, interaction and practical cooperation with partners, nations and international organizations; and access to a Bi-SC organization (MPD) with a mission that is tailor-made to support their work in the Western Balkans. More important, it would place oversight of the NATO liaison elements where it rightfully belongs — at the strategic level.

In addition to modifying command and control (C2) relationships for NHQSa, MLO Belgrade and NLO Skopje, NATO should establish a C2 headquarters in the Western Balkans to supervise, coordinate and integrate the activities of those three liaison elements and any new ones that might be created. Further, the Alliance should place key leaders at that C2 headquarters on full, two- or three-year assignments, just as members of the military attache corps in those countries are placed. Today, those leaders are assigned for relatively short deployment-like tours, lending to diminished continuity and continually interrupted momentum. A NATO C2 headquarters on the ground, with key leaders on stabilized tours of duty, would send a strong message about NATO’s commitment to security and stability in the Western Balkans. It would also highlight the value the Alliance places in developing our partners’ — and potential future members’ — defense institutions. That C2 headquarters would serve as a focal point for oversight, coordination and collaboration under the supervision of a leader and staff who execute those responsibilities as their sole, full-time duty.

The EUCOM JCTP model can be useful in exploring options for these proposals. The program had a C2 element at EUCOM HQ in Stuttgart that was staffed by a combination of active-duty service members on three-year assignments and reservists on renewable one-year tours, many of whom remained in place for three years or more. That C2 element supervised, coordinated and supported the activities of in-country Military Liaison Teams (MLT) comprised of four to six members each and augmented by host nation personnel. The MLTs worked in host nation facilities (typically within the Ministry of Defense or general staff) in the same way as the NATO Advisory Team in Sarajevo and the offices in Belgrade and Skopje.

Each MLT worked with its host nation counterparts to write a country work plan (CWP) that listed the goals and objectives for host nation transformation, development, professionalism and NATO interoperability. Partner nations and MLTs revised CWPs continually, reflecting progress toward goals and objectives and adding emerging ones. Each goal was crafted to be achievable in three to five years and included supporting objectives that could be achieved in one to two years. Many of the JCTP goals and objectives were designed to contribute directly to the host nation’s PfP goals. When external assistance or expertise was required to help meet an objective, the MLT coordinated with the JCTP HQ for support by a USEUCOM staff element, a U.S. service component command in theater, an appropriate active component military unit or agency in the U.S., or the host nation’s partner state within the U.S. National Guard’s State Partnership Program. Eleven partners leveraged JCTP’s synergy and focus in achieving their NATO partnership objectives and, ultimately, their successful accession to NATO membership.

Because NATO has all of the elements at its disposal right now to make this shift in command, control and coordination of partnership activities in the Western Balkans, minimal investment will be required. All of the expertise needed to guide defense and security sector reform and coordinate PfP activities across the region resides today at NHQSa. The focus of that expertise could be effectively broadened to include oversight of and collaboration with the NATO liaison elements in BiH’s neighboring partner nations. With minimal coordination, a new “NATO HQ Balkans” could begin work in existing NATO facilities at Camp Butmir or at the BiH MoD in very short order. The result would be an engagement activities focal point at the strategic level with enhanced day-to-day coordination and collaboration.

Just as the USEUCOM JCTP HQ in Stuttgart facilitated each MLTs’ execution of their CWPs, NATO HQ Balkans would facilitate — through their direct access to the Alliance’s strategic-level headquarters and agencies — MLOs’ execution of the various NATO partnership plans, programs and tools in use by their host nations. It would be positioned to coordinate and integrate activities on a continuous basis, rather than at periodic working group meetings. It would also be well-positioned, via the strong working relationship that NHQSa already enjoys with the diplomatic community in Sarajevo — NATO and partner ambassadors and defense attaches — to integrate national bilateral activities among Balkan partners. These efforts would create a synergy in NATO engagement activities that the Alliance has so far been unable to achieve within the current C2 structure.

Status quo dangers

When I arrived in Tuzla, BiH, in the summer of 2002, charged with coordinating civil-military operations for Multinational Division-North, IFOR/SFOR had been on the ground in BiH for nearly seven years. One of our primary tasks was to coordinate the work of the wide array of governmental and nongovernmental bodies that provided humanitarian relief and reconstruction resources in the wake of the brutal armed conflict that had devastated the country and its people. The timing of my deployment gave me an up-close view of the phenomenon called “donor fatigue.” Those organizations had successfully provided for the most urgent needs, but were growing impatient in areas in which providing assistance was more difficult due to corruption, political in-fighting or lack of local leadership. As a result, resources for our work in BiH had begun to shrink as international donors focused their efforts elsewhere.

Ten years later, I experienced a kind of deja-vu as commander of NATO HQ Sarajevo. NATO had been on the ground in the Balkans for nearly two decades with a mission that evolved from mostly peace enforcement to mostly defense and security sector reform. The most important aspects of our work, specifically in Bosnia-Herzegovina, had stalled, mostly due to internal political impasse. As a result, members of the international community had displayed very clear signs of what I will call “engagement fatigue.” Some had begun to express open frustration at Bosnian political leaders’ inability to make progress on key Euro-Atlantic integration objectives. Meanwhile, despite the obstacles that their elected and appointed civilian leaders continually thrust into their paths, the Armed Forces of Bosnia-Herzegovina had progressed and improved admirably, culminating in multiple NATO deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

NATO and the broader international community cannot afford to allow engagement fatigue to take us down the same path on which donor fatigue took us in the Western Balkans. We cannot simply congratulate ourselves for whatever level of success we’ve been able to muster, to surrender our higher goals and those of our partners in the region, to fold our tents and go home. Doing so will undoubtedly open the door to renewed instability and diminished security. We must re-evaluate, reorganize and refocus our engagement efforts to continue to improve security and stability in the region.

Comments are closed.