Putin’s War of Choice and What Comes Next

By Lt. Cmdr. Travis Bean, U.S. Navy

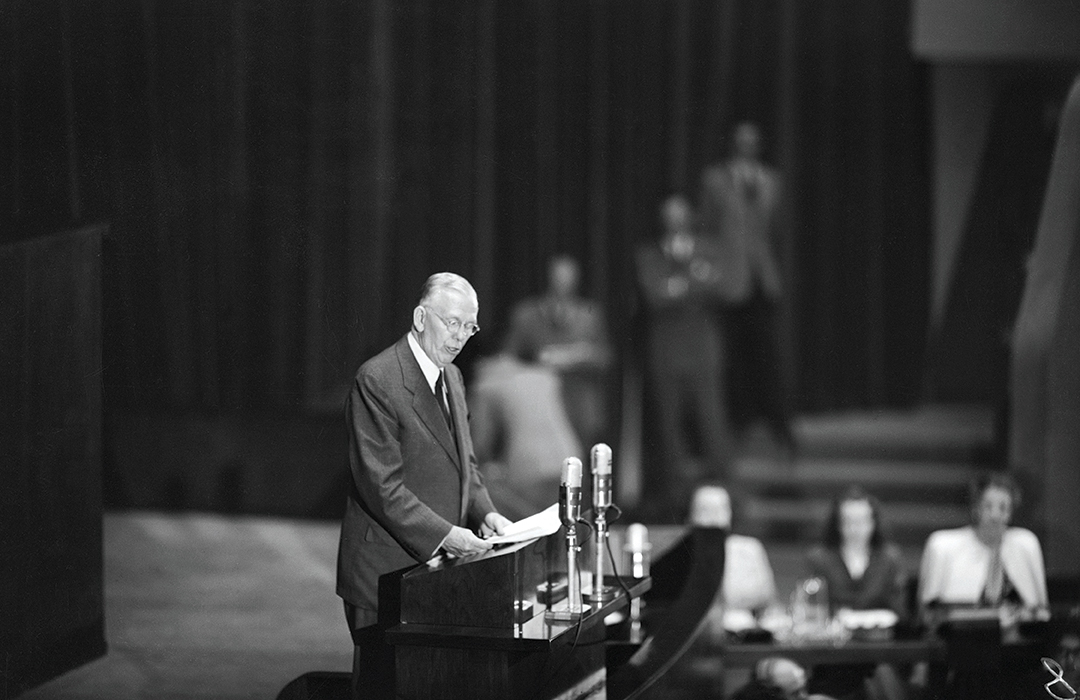

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower once quipped: “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” To this end, the United States and its allies must start planning for the possibility that Russia’s continued losses in Ukraine put the Kremlin’s stability in question.

In mid-November 2022, the Russian army retreated from Kherson, the only major city taken after the beginning of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. This retreat occurred after Russia’s numerous battlefield defeats in the east. Moscow’s army once stood at the gates of Kyiv; now they are losing ground nearer to their home turf and have resorted to long-range missile attacks against innocent people and civilian infrastructure. Things are not going well for Putin. Though the war’s eventual result is far from certain, the U.S. and NATO must be prepared for a governmental collapse in Russia. A Kremlin regime failure may be rapid and could open a narrow window for the West to reshape the global security environment after Putin. That window of opportunity to mitigate the damage caused by a weakening Kremlin may be small, so planning to guide the deteriorating authoritarian state toward democratic values is essential.

Planning pitfalls

Writing in Foreign Affairs magazine about Russia’s apparent declining power, authors Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Michael Kofman invoked an old adage: “Russia is never as strong as she looks; Russia is never as weak as she looks.” Planners should therefore be wary of the pitfalls and unknowns when approaching an ostensibly weak Kremlin. While Putin may reign for decades more, he may well soon be retired to his dacha.

Despite reports that Putin’s health is declining, such rumors have yet to be confirmed by any reliable source. However, biology catches up to us all — even long-reigning autocrats. Putin turned 70 years old in October 2022 and has already eclipsed the male life expectancy in his country, according to the World Bank’s calculations. His time left as president, and his time left on Earth, may be short. Though he has carefully crafted his regime to be “coup proof,” the possibility exists that declining health may affect his ability to play a role in managing his successor. Further, if he is unable to select a replacement, that may bring a quicker end to his military adventure in Ukraine.

The successor question is an important one, as the answer will greatly affect the character of post-Putin Russia and its desire to be belligerent toward its neighbors and NATO. Robyn Dixon, The Washington Post newspaper’s Moscow bureau chief, highlights that some Russia-followers think that Putin’s successor “would have to be a centrist acceptable to the elite, who could end the war and build bridges to the West.” To this end, Dixon specifically mentions Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, a technocrat who led his city through the COVID-19 crisis and hosted the 2018 World Cup. The relevance of the combined factors of Putin’s age and the cost of the war in Ukraine increases daily, gradually granting Moscow’s oligarchs more agency in the selection of the country’s next leader. Considering their choice will have an immeasurable effect on their bank accounts, it is likely they would choose someone more centrist than Putin. However, if Russian history demonstrates anything with respect to regime change, it is that disorder is the rule and predictions can be difficult.

Though it appears from the outside that Putin and his oligarchs maintain tight control over governmental affairs, this structure may not be as strong as it seems. One must recognize the role of the restricted media in Russia and the affect it has on the country’s citizens. In particular, the use of Russian television outlets as a mouthpiece for the government has maintained Putin’s popularity and left the public in a fog about their country’s losses in Ukraine. The Kremlin has also quashed dissenting media outlets such as the independent Novaya Gazeta newspaper. Yet the media restrictions give credence to the notion that at its core, the Russian government is, to some degree, accountable to the public. If it were not, this authoritarian control of the media would not be necessary. Anatol Lieven, a senior fellow at the Quincy Institute, says, “If you get a public split in the regime and the losing faction appealing to the streets, that is the moment when revolution, I mean mass popular unrest, really does become possible.” Media censorship affects what people think, and Russian popular opinion provides a foundation for government action. If the Kremlin were to lose its ability to control the narrative, the very foundation of the authoritarian state would be in jeopardy.

Should the assault on Ukraine strategically fail, one major complication will be the control of Russia’s multiarmed and decentralized military. Given that the offensive operations in Ukraine are being fought by a number of mercenaries, national guard units, regional militias and the regular army, a deteriorating defensive situation for Russia implies that peace agreements will necessarily be more difficult. Similarly, should the Russian government collapse before completing military operations in Ukraine, command and control of these disparate units also becomes problematic.

Perhaps the greatest caution to take would be preventing the humiliation of the Russian people. An example of how to do this can be found in the Marshall Plan and the overall reconstructive strategy in West Germany after World War II. In it, those most responsible for the heinous crimes of the Holocaust were held to account, while simultaneously the victors helped rebuild the defeated state’s economy. Similarly, should Russia be defeated in Ukraine, NATO must not pursue punitive economic measures against Moscow.

Supporting Russia post-conflict

Some Russia observers have already documented the current decline of the Kremlin. Former Russian diplomat Boris Bondarev has written about the possibility of the war in Ukraine causing Putin’s downfall, suggesting that the “best thing the West can do isn’t to inflict humiliation. Instead, it’s the opposite: provide support.” As someone with a breadth of experience in the Russian government, Bondarev’s outlook is both insightful and backed by institutional knowledge. A recent Foreign Affairs magazine article uses more measured language, encouraging the U.S. to approach a declining Russia with caution. The author states that the country “goes through cycles of resurgence, stagnation, and decline [and that the] threat may evolve, but it will persist.” Russia observers and academics continue to have a negative outlook for the future of the Kremlin in its current form. This view is supported both by current facts and observations, as well as historical patterns.

The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s was one of many factors that led to its downfall. There are some important parallels to note between the Afghanistan and Ukraine invasions: the combined effects of equipment losses, geopolitical embarrassment and immense numbers of war dead again create historical conditions for regime change in Moscow. Yet, history demonstrates that such conditions are brought on quickly and may be short-lived.

With today’s belligerent Russia as a frame of reference, it is difficult to imagine how close to total peace NATO and the Kremlin were in the early 1990s. Early in Boris Yeltsin’s term as president, for instance, his government even considered applying for membership in NATO. The peace dividend of the Cold War also included a massive reduction in Russia’s nuclear arms. History tends to repeat itself, and the situation after the final Russian troops leave Ukraine may prove to be no exception. It is possible that the next person to fill Putin’s role may be pragmatic and West-leaning like Yeltsin. NATO should be prepared for the possibility of a future partner in Moscow, so that an opportunity for peace is not lost.

Another example of authoritarian retrenchment in early 1990s Russia was in the country’s transition to a market economy. As Fiona Hill, a former official with the U.S. National Security Council, describes in her book “There is Nothing for You Here,” Russia’s oligarchs quickly and deeply imbedded corruption in Russia’s evolving economic infrastructure. This in turn set the tone for what would become a Russia corruptly controlled by a rich few. In hindsight, one may reasonably argue that this was a missed opportunity for the NATO bloc to reshape Russian economic norms before they were derailed. However, the evolution was fast-paced and somewhat unprecedented. What NATO can do now, armed with the knowledge of history, is be ready for a future scenario where conditions are favorable for the creation of a rules-based and equitable Russian economy.

Should Putin be defeated in Ukraine, the U.S. should consider economic assistance for Russia akin to the Marshall Plan. The reasons are twofold: First, even after a bitterly fought World War II, the U.S. invested a great deal of time and effort into rebuilding Europe. This provides a historical precedent for how rebuilding a former adversary nation may be done.

And second, the period directly after the fall of the Soviet Union can be seen as a missed opportunity for rebuilding a stronger, more democratic Russia. There is a potential for such a governmental failure to happen again, and NATO should not miss another opportunity to convert an adversary into a partner.

The objective end

In the unlikely scenario that the Russian government collapses in the wake of the war in Ukraine, and if the environment is sufficient for external influence, the question remains: What would be the end objective? The answer is, in short, a less aggressive and more stable Russia. In a hypothetical post-Ukraine conflict era, NATO countries have a chance to reduce the likelihood of a future conflict started by Moscow. To do so, they need to apply the lessons learned from the assistance given to Europe and Japan after World War II, and those learned by Russia in the period immediately after the Cold War.

What should be done then? In order to work toward a peaceful future, Western democracies should keep in mind George C. Marshall’s own words in his Marshall Plan speech: “Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.” Clearly, the first step in the process would be to provide life support to the Russian economy. By doing so, NATO could hope to further bolster free institutions by undertaking the following:

- Support democratic values in a new government. The framework for a democratic Russia exists already considering the country has a parliament, constitution, regular elections and even dissidents. However, these things exist as a Potemkin village. NATO and the European Union should send experts to coordinate with their democratic counterparts in Russia to buttress standard democratic norms.

- Support a rules-based and equitable market economy and fortify it against cronyism and kleptocracy. Hill identified Moscow’s rocky transition from communism to a market economy as a precursor to the current authoritarian regime. Assisting a post-Putin Russia with transition to a rules-based market economy will have a manifold effect on Russians’ quality of life and economic health.

- Support nuclear arms reduction and security cooperation with Russia. Efforts to assist in rebuilding the country may pay dividends in the form of a new and strong ally for the West, should such efforts succeed. At the same time, there should be consideration of denuclearizing Russia. This should not be the first item on a rebuilding agenda, but it is a goal worth pursuing. Notably, Russia, among other nuclear powers, is treaty bound to pursue elimination of its nuclear weapons arsenal.

The U.S. poured large sums of money and a good deal of expertise into Europe and Japan after World War II. The results of these investments contributed to the foundation of peace, stability and security still seen today. The Marshall Plan in Europe provides a template for how the U.S. and NATO may effect similar change in Russia. Similarly, the Yeltsin era and the associated failure of democratic and economic norms to flourish provide a reason for NATO to get involved early in Russian reconstruction. There may be a brief period after the war in Ukraine for the U.S. and its allies to sow the seeds of a more peaceful future — and planners should be thinking about how to do so.

Comments are closed.