Strategic Deterrence in the Nuclear Era

By Dr. Pál Dunay, Marshall Center professor

Soon, it will be eight decades since the inception of the nuclear era. The world must live with nuclear weapons — they cannot be uninvented, as then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher called our attention to in 1982. More than 40 years have passed and the statement has stood the test of time. The nuclear era is irreversible and continues unabated. However, the primary, if not sole, rationale for the existence of the world’s deadliest weapons must be to reduce the danger of war.

The existence of nuclear weapons is regularly cited as a reason the so-called long peace held during the four decades of the Cold War. Whether a single class of weapons can hold the peace is open to debate, but few would dispute that the amassing of large nuclear arsenals contributed to the long peace. This belief was underlined by what used to be called Cold War thinking. While the term carries some ambiguity, it is a commonly shared view that Cold War thinking entails not only deterrence but also a readiness to engage in nuclear war. Following the Cuban missile crisis, substantive efforts were made to reduce the level of confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, the world’s two nuclear great powers. The first major arms control agreement, the Partial Test Ban Treaty, is often mentioned in this context. However, in the 1960s a doctrine of flexible response spread from the U.S. to NATO and began to replace the massive retaliation doctrine. It carried the message that an armed conflict between the nuclear great powers (and their allies) does not necessarily have to lead to nuclear escalation. It is not surprising that the flexible response doctrine has outlived the Cold War.

Horizontal proliferation

One element of nuclear history that bridges the Cold War and the current era is the strong aversion by the U.S. and the Soviet Union/Russia — and for that matter, all five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council — to an increase in the number of states possessing nuclear weapons. The development of nuclear programs by countries without them is known as horizontal proliferation. The aversion to this proliferation is reflected in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) signed in 1968, the world’s most successful multilateral arms control agreement. The U.S., the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom played prominent roles in achieving it. Of course, it can be argued that, despite the treaty, the number of de facto nuclear powers increased from five to nine. However, this happened over more than half a century, while several states gave up their nuclear aspirations (one state, the Republic of South Africa, abolished its small nuclear weapons stockpile) and the five legitimate nuclear weapons states retained their unity in rejecting the nuclear ambitions of other states. This is a significant achievement. During the past half-century, traditional nuclear powers have often had close relations with one de facto nuclear power or another. Consider the links between the U.S. and Israel, China and North Korea, and the Soviet Union/Russia and India. However, a majority of the states in the world, including most of the 191 state parties of the NPT, do not support nonnuclear states becoming de facto nuclear states.

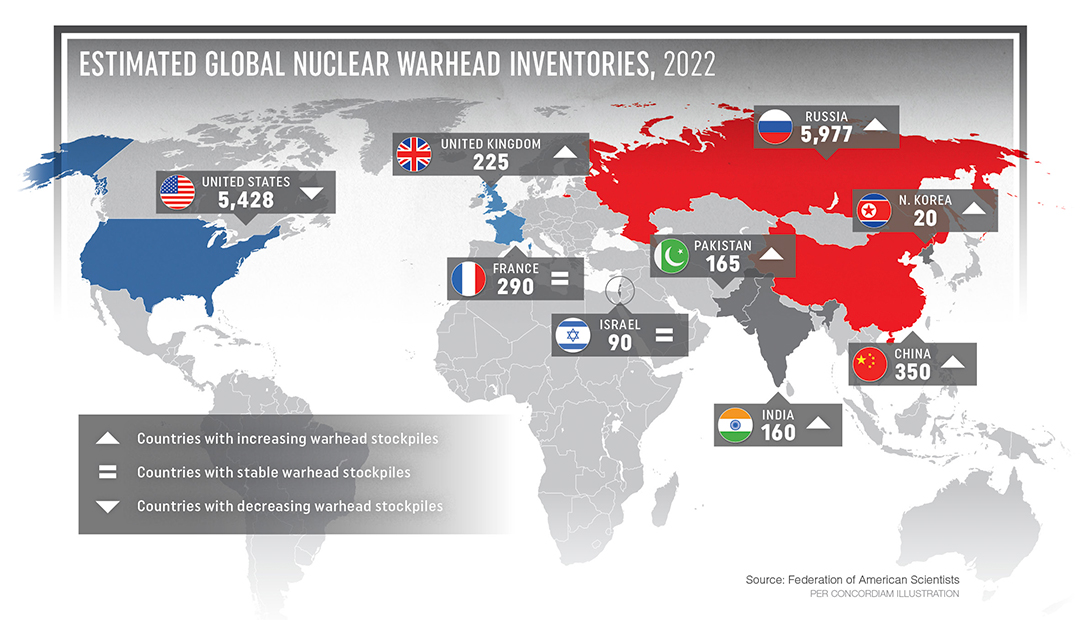

The Cold War left the world with an arsenal of approximately 65,000 nuclear devices. However, the arsenal started to shrink after 1987 because of the U.S.-Soviet Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) and subsequent unilateral and reciprocated cooperative reduction measures. The question, “How much is enough?” has become more pertinent than ever. Russia and the U.S. lived up to their NPT responsibilities. The treaty obliged the parties to undertake nuclear disarmament. Understandably, this was the foremost task of leading nuclear powers. Over 35 years (between 1987 and 2022), 80% of the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles were eliminated. This is certainly an achievement, though it may not affect our perception of security because the capacity for nuclear overkill remains. With the elimination of those Russian and U.S. nuclear weapons — and with the growth of the Indian, Pakistani and, to a lesser extent, North Korean arsenals — the share of the world’s nuclear arsenal owned by the two superpowers shrank to approximately 92%.

In the first two decades of the post-Cold War era, there were concerns related to nuclear arsenals. But those concerns were part of a very different security agenda than the one that had prevailed during the Cold War. In the 1990s, five concerns dominated the agenda:

- The physical control of Russian nuclear weapons, the so-called loose nukes challenge.

- The possession of nuclear weapons by Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine as successor states of the Soviet Union, and the return of the weapons to Russia.

- The horizontal proliferation of nuclear weapons in India and Pakistan.

- The alleged and, as later revealed, interrupted nuclear program in Iraq.

- The potential access to fissile material by nonstate actors for building dirty bombs.

A new security agenda

The 9/11 terrorist attacks changed the security agenda. Interstate security relations among the main nuclear powers, at least temporarily, mattered less than before. Russian President Vladimir Putin challenged the international distribution of power — as demonstrated by his speech at the 2007 Munich Security Conference (when he openly rejected the post-Cold War security order), and in Russia’s war against Georgia in August 2008. The danger of a return to interstate rivalry between Russia and the West has been present ever since. The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) in 2010, initiated by the U.S., and Russia’s demonstrated interest in a reset gave hope that a new era of adversarial relations could be avoided.

Russia had benefited from economic advancement between 1999 and 2012 and increased its investment in the defense sector. This could be interpreted in various ways. The benevolent, if not outright naive, interpretation could draw the conclusion that it compensated for a long period between the late 1980s and the early years of the 21st century when Russia did not prioritize its military. A less naive conclusion is that Russia wanted to return to the “high table” of world politics. This was clear not only from its military modernization efforts but also from its political pronouncements, in particular Putin’s unceasing claim (first made in 2005) that his country wanted to be at the center of a multipolar international order. If the armed forces are Russia’s most important source of power, then it was logical to conclude Russia’s “recovery” would be based on the consolidation of its military might. And Russia’s official documents left no doubt about the importance of nuclear weapons. Russia regards them as the ultimate deterrent. Aware of the perceived loss of its conventional military superiority, Russia is increasingly tempted to rely on its nuclear forces. The documents vary as to the contingencies in which nuclear weapons would be employed. Would it be in the defense of Russia proper and also its allies? Or only if attacked by a nuclear-weapon state?

A moral inhibition

A deterrent posture always consists of two elements: the existence of the capability and the readiness to use it. Russia, with the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, certainly possesses the former and its declared policy leaves no doubt about the latter. However, every nuclear weapons state faces the following challenge: Nuclear weapons have not been deployed since August 9, 1945. More than 77 years have passed and the moral inhibition has been mounting against nuclear weapons use. This is complemented by various international agreements adopted between 1982 and 2022, each declaring that a nuclear war cannot be won and must not be fought (or a variation of this language). Although the documents have no bearing on the world’s nuclear capacities, they contribute to the strength of the moral inhibition.

There is no universal legal prohibition banning nuclear weapons or their employment. The International Court of Justice, in an advisory opinion adopted in 1996, could not conclude that the use of nuclear weapons would be illegal and stated: “… in view of the current state of international law, and of the elements of fact at its disposal, the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defence, in which the very survival of a State would be at stake.” The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that was opened for signature in 2017 and entered into force in 2021 does not have a single state with nuclear weapons among its parties. In summary, nuclear deterrence continues to hold. There is a quest to constrain the existence of nuclear arsenals to their deterrent function, but that has not yet been achieved.

It is worrying that an opposite trend may be emerging. Recently, in the heated atmosphere of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, concerns were raised that Russia would escalate the conflict by employing a nuclear weapon. In fact, beginning with its Zapad-99 exercise, Russia has integrated a scenario into its military training that is called “escalate to deescalate.” It means that if Russia could not prevail in a conventional conflict, it would use a nonstrategic nuclear weapon to be followed by negotiations, under the theory that the other party (and most likely the collective political West) would want to avoid nuclear escalation. Several subsequent exercises indicate that Russia’s military considers this an option. What lessons can be learned from such a Russian approach? It indicates that Russia could imagine a contingency wherein the nuclear threshold is crossed out of necessity. It is also a starting assumption by Moscow that the West will not engage in nuclear escalation and that the West indirectly recognizes that Russia is capable and ready to continue to escalate if faced with a nuclear response.

Public condemnation may be the reason that Russia did not carry out recent exercises with an element of nuclear escalation, or at least did not publicly reveal that it did so. During Russia’s war against Ukraine, the danger of a tactical nuclear escalation has been widely debated in Western circles because of the military setbacks Russia has suffered. The West made it clear that it would not engage in nuclear escalation in response to a low-yield nuclear strike. It is understandable that the West cannot reveal in detail its possible reaction to Russian nuclear escalation. Despite this ambiguity, it was made clear that the reaction, while not nuclear, would have catastrophic consequences for Russia.

China’s nuclear ambitions

While nuclear deterrence is primarily interpreted in the U.S. (and across the West) in a Russian context, some rearrangement of this thinking is needed because of China’s plans to build a substantial nuclear arsenal by 2030. China’s aspiration to possess 1,000 nuclear warheads will separate it from countries with smaller nuclear arsensals, but leave it lagging significantly behind the Russian and U.S. arsenals. A key question is whether the arsenal is for deterrence or warfighting. The focus of nuclear deterrence has been moving away from the sheer number of warheads to other factors, such as the survivability of nuclear arsenals (which led to the development of land-, sea- and air-deliverable components known collectively as the nuclear triad); the quality of the warhead delivery vehicles, including missiles, submarines and airframes; and the ability to overcome evolving missile defense systems.

The advancements of missile defense capabilities do not make the U.S. and other states that are introducing them immune from a massive Russian strategic nuclear attack. Still, Russia’s view is that ballistic missile defenses weaken its capacity to launch a successful nuclear strike. Its reaction has been twofold: to develop higher velocity (i.e., hypersonic) missiles that can penetrate missile defenses, and to bolster its nuclear arms infrastructure. Whereas the former has been partly realized since 2019, the latter is in its infancy and may require efforts and resources that are not available to Russia in the middle of its high-intensity war in Ukraine.

It is apparent that Russia wants to retain nuclear deterrence at the core of its military strategy. That theory is supported by Moscow’s declared policy and by the verbal threats that are supported by videos of the Tsirkon hypersonic missile and the Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched cruise missile. The current state of affairs is reflected in the unclassified version of the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), published in October 2022. The document reflects the reality that there are four main nuclear challengers: Russia, China, North Korea and Iran. Each presents a different challenge, although they are united by being potential adversaries of the West. It is understandable that the language addressing Russia is harsh. Russia is diversifying its nuclear arsenal and regards its nuclear weapons as “a shield behind which to wage unjustified aggression against [its] neighbors.” The role of the U.S. nuclear arsenal is not confined to deterrence exclusively, though that remains its fundamental role. It provides security assurances to allies and partners, and the ability to achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails. The U.S. further underlines the priority of deterrence in its nuclear posture when it specifically points out that it “will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.” This exempts all but a few nonnuclear weapons states that may face U.S. nuclear power. It certainly includes North Korea and Iran; the former withdrew from the NPT and the latter apparently does not live up to its commitments.

Conclusion

Despite the meager prospects of arms control and crisis management, the NPR avoids being a hawkish document overtaken by the events unfolding at the time of its drafting. It is clear the U.S. does not want to overreact to the current high tensions with Russia and the mounting rivalry with China, and resisted the temptation to provide its main nuclear opponents with an excuse to escalate tensions. Arms control is at a stalemate between Russia and the U.S. Although U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration extended the New START Treaty in February 2021 for another five years, that continuation was set aside by Putin’s suspension of the treaty in February 2023. This means that the treaty can survive, but only if fundamental changes occur in Russia, including ending Russia’s war against Ukraine in a manner satisfying to the treaty’s two parties.

Comments are closed.