How a simple formula complicates defense spending

By Jack Treddenick

The amazing thing about NATO at 70 is that it is still here. Looking back, this surprising longevity has been largely due to its uncanny ability to adapt and evolve in the face of extraordinary change in the international environment. But the Alliance has also successfully endured serious existential threats arising from its own internal tensions. Foremost among these has been the prickly and persistent issue of burden sharing and specifically the disproportionate share of the Alliance’s defense efforts borne by the United States.

The intensity of this issue, and hence its potential to undermine the cohesion — and even the existence — of the Alliance has waxed and waned over the years, eventually to quietly recede, leaving intact both the Alliance and its unequal burdens. But as NATO marks its 70th birthday on April 4, 2019, political change in the U.S. has brought the issue into such glaring visibility that it appears certain that either some significant rebalancing will occur, or NATO, whose obituary admittedly has often been written prematurely in the past, will actually pass into history.

Playing the game

Every U.S. administration since the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949 has expressed annoyance and frustration with the failure of its allies to make greater expenditures for defense. When strategic arguments failed to inspire them to do more, U.S. leaders frequently resorted to signaling, with varying degrees of subtlety, the possible withdrawal of American forces from Europe, thereby removing the most tangible proof of American commitment to European security. Only four years after the signing of the treaty, the Eisenhower administration threatened an “agonizing reappraisal” of its commitment. In the 1960s, President John Kennedy complained of rich NATO countries not paying their fair share and threatened rapid troop withdrawals from Germany. More recently, President Barrack Obama warned the United Kingdom that it would no longer be able to claim a “special relationship” if it did not spend 2 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense. And in 2017, then-Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis issued an ultimatum to NATO defense ministers that unless they increased defense expenditures before the end of the year, the U.S. might have to “moderate its commitment” to the Alliance.

Generally, when these threats became sufficiently credible, allies have committed to increased defense efforts, and occasionally, depending on security pressures, they would actually follow through. They would continue to do so, seemingly, until the U.S. was appeased or distracted by other events. The U.S. argument that wealthy Europe (and Canada) could do much more in its own defense remains unassailable. But tolerating some degree of asymmetric burden has also served America’s interests. Low European expenditures ensured European security dependence on the U.S. and thus legitimized its role as leader of the Alliance. It also justified a large U.S. military presence in Europe, allowing it to simultaneously support NATO and to project power beyond Europe.

The rules of the NATO burden-sharing game therefore seem quite straightforward: The U.S. attempts to balance its demands for increased European defense expenditure with concerns that expenditures do not reach the level where European defense autonomy and subsequent independence in global affairs are encouraged. The Europeans, in turn, search for the lower limit that the U.S. will accept without weakening its commitment to European defense, simultaneously holding in check any enthusiasm they might otherwise have for a united European defense capability.

To date, playing to these rules has been remarkably successful in preserving the Alliance.

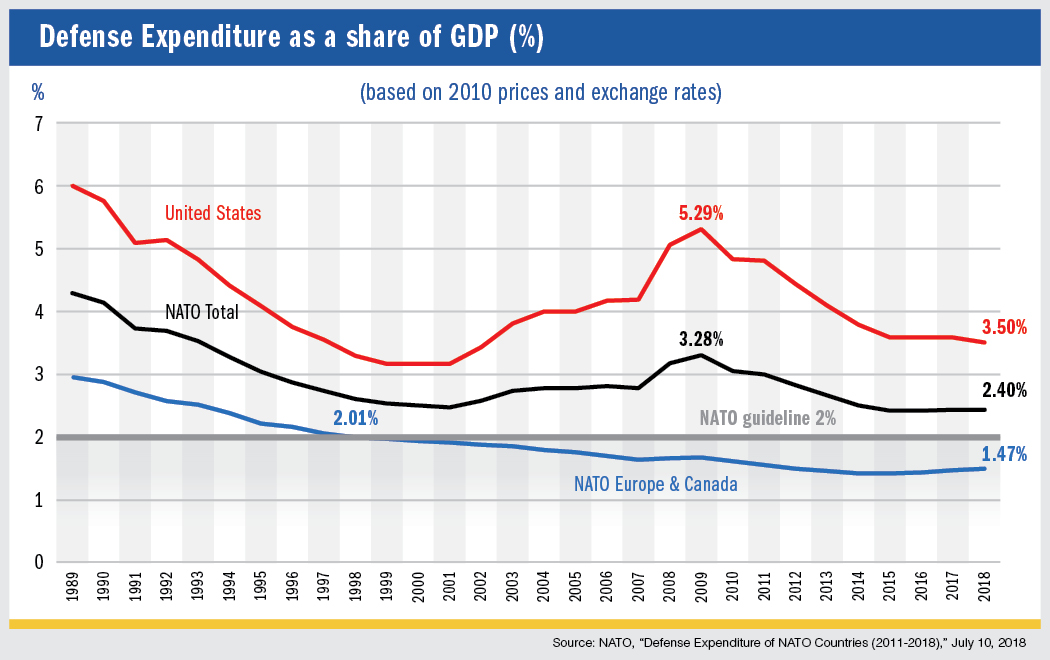

How this game actually plays out, however, depends very much on the security environment. Thus, in direct response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its invasion of eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014, the U.S., after decades of gradual withdrawal from Europe, launched the European Deterrence Initiative, significantly increasing U.S. troop strength and direct defense expenditures in Europe. Subsequently, at the Wales summit in September 2014, NATO members agreed to a defense investment pledge to reach defense spending levels of at least 2 percent of GDP within a decade, and of that expenditure, they would spend no less than 20 percent on new equipment. European members, for the most part, appear to have taken the pledge seriously. To date they have increased defense expenditures by an impressive 14 percent in real terms, which compares to a U.S. increase over the same period of only 2 percent. And, in a remarkable turnaround, they have, in aggregate, halted a quarter century of decline in the share of total GDP going to defense, though the current European share of approximately 1.5 percent remains low compared to the U.S. share of 3.5 percent.

But even before the events of 2014, European complacency with regard to its defense and security dependence was eroding, not only because of the gradual reduction of the U.S. military footprint in Europe, but also the apparent shift of U.S. strategic focus to the Western Pacific. The realization that Europe is but one area of U.S. strategic interest, and not necessarily the most important one, raised apprehensions that the U.S. may no longer be willing to play the burden-sharing game according to the old rules.

Between a rock and a hard place

At another level, though, the U.S. continues to stress the value of NATO. Both the U.S. National Security Strategy and its National Defense Strategy underline the linkage between European defense cooperation and American prosperity and security. It is a position vigorously supported not only by the American foreign policy and defense establishments, but also by Congress, which only recently unanimously approved a resolution supporting NATO.

Maintaining this level of support in the current environment, however, will very likely only be possible if European NATO can demonstrate that it is indeed taking on more of the NATO burden. It is in this context that so much significance has become attached to the 2 percent spending criterion. Whether Europe is meeting U.S. expectations sufficiently to ensure continuance of security guarantees has, for the moment and for better or worse, come down to whether the European allies as a whole and individually are spending at least 2 percent of their GDP on defense.

Despite a natural reluctance to be seemingly coerced into increasing defense expenditures, Europe would appear to have little choice but to strive to do so, especially when the threats are intertwined with similar tactics on trade balances and tariffs. Just prior to the June 2018 meeting of NATO defense ministers, when Secretary Mattis forcefully demanded increased allied defense expenditures, the U.S. announced forthcoming steel and aluminum tariffs on Canada and the European Union, justifying them on the basis of national security.

The belief that the U.S. will not make good on its threat to reduce its commitment to Europe is arguably more fragile today than in the past. Indeed, it might be argued, both in America and in Europe, that U.S. withdrawal from Europe would not necessarily be a bad idea, but rather the impetus that Europe needs to get serious about its own defense and to create an autonomous and effective defense capability. This is unlikely to happen. To make sense, both militarily and financially, such autonomy would require at a minimum a single European defense policy and almost certainly the creation of a single European military force. These are unreal ambitions, especially given the EU’s track record in dealing with defense issues. Moreover, at a time when the cohesion of the EU itself is under extreme stress from so many different directions, including immigration pressures, Brexit and rising anti-EU populism, this is probably not the most auspicious time to be advocating even more European centralization. Finally, since burden sharing is primarily about money, the financial effort required to create a European defense capability equivalent to that provided by NATO would almost certainly be much greater than that required to meet the 2 percent challenge currently on the table.

So easy to remember

The 2 percent fixation really represents a triumph of sloganeering over complexity and implies that the NATO burden-sharing issue is merely a dispute over money. The constant repetition of this easily grasped number with its aura of analytical precision has turned it into a persuasive icon of accepted wisdom about defense spending. The reality is, however, that there has never been any analytical justification for it. It has never been established, nor is it even conceptually likely, that 2 percent of European GDP would somehow provide the right amount of military capability required to support NATO’s strategic objectives.

It is true, however, that the share of GDP allocated to defense is a useful measure of defense burden in the sense that it is a measure of what a nation gives up in terms of other things it could accomplish with the same resources: personal spending, industrial investment, public infrastructure, education, health, pensions and so on. It is less useful as a measure of comparative burdens or defense efforts among countries. For one thing, there are certain accounting anomalies that have to be sorted out, particularly regarding exactly what constitutes a defense expenditure. While NATO does have a standard definition for defense expenditures, it includes, for example, military pensions, which in some countries are paid by defense ministries and in others by central pension authorities. In some member countries, such payments represent a significant part of what is claimed to be defense expenditures, but contribute nothing to current military capabilities. Likewise, some countries account for paramilitary police forces in defense budgets; others do not. Expenditures for health care, especially for dependents of military personnel and for veterans, are also included in some national defense budgets but excluded in others where they are provided as part of national health care programs. The U.S., for example, spent over $50 billion on military health care in 2017, an amount larger than the total defense expenditures of any other NATO country other than the United Kingdom. All of these conceptual problems are further complicated by exchange rate swings, differential inflation rates, and other sorts of statistical issues that can invalidate comparisons of defense burdens measured by spending.

A further issue with using share of GDP as a measure of NATO burden sharing is that no country directs all of its defense expenditures exclusively to providing NATO-related capabilities. This is particularly true of the U.S., with its worldwide security interests. As a result, the 3.5 percent of GDP that the U.S. spends on defense globally gives no indication of what it spends solely on the Euro-Atlantic area. While it is impossible to impute total expenditures to specific geographical areas with any precision, rough estimates of American spending for European defense range from 15 to 25 percent. Thus, as the European allies are always quick to point out, comparing U.S. defense expenditure with European expenditures is misleading and grossly overstates the U.S. contribution. But it can also exaggerate the resources and capabilities actually available to the Alliance and thereby dull European resolve to provide more.

But these are minor issues. The fundamental flaw in focusing on the defense share of GDP as a measure of Alliance contributions is that the linkage between money expenditure and capability delivered is extremely ambiguous and varies widely from country to country. Capability itself is a multidimensional concept depending not only on the size and structure of national forces, but also on their equipment, their availability, their deployability, their sustainability, their agility, their interoperability with other allied forces and, most important, on the political will to use them. Not all of these attributes can be reduced to simple money terms.

Where did this come from?

If the 2 percent criterion is such a flawed measure, then where did it come from? It appears that NATO simply drifted into it. As indicated in the chart on page 13, average defense expenditures in NATO Europe declined steeply from approximately 3 percent of GDP at the end of the Cold War in 1989 to approximately 2 percent a decade later. Over the same period, U.S. expenditures fell more precipitously, from 6 percent to 3 percent of GDP. It was becoming unpleasantly clear that, if these trends were to have continued, European expenditures would fall below a highly symbolic 1 percent within a few years and, because U.S. expenditures were falling at a faster rate relative to GDP, they would reach roughly the same level at roughly the same time.

However, the fall in U.S. expenditures was abruptly reversed following the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent large spending increases were sustained by the trillion-dollar wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Concurrently, in the wake of the 2002 Prague summit and NATO’s decision to conduct military operations outside of NATO’s geographic area, member countries committed to a comprehensive and expensive set of capability requirements. To finance these aspirations, they further undertook a “gentlemen’s agreement,” never officially promulgated, to halt the decline in their defense expenditures with a view to attaining levels close to 2 percent of GDP. Despite the good intentions, European defense expenditures as a percentage of GDP continued to decline apace.

The first published reference suggesting that NATO was becoming increasingly focused on 2 percent as a lower boundary for defense expenditures appeared in the 2004 NATO expansion treaties — the “big bang” expansion that included Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia — in which all committed to spend a minimum of 2 percent of their GDP on defense. Despite this increasing consensus, European expenditures as a percentage of GDP continued their relentless decline. By contrast, in the wake of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the U.S. continued its spending increases, peaking at 5.3 percent of GDP in 2009 and only falling thereafter as debt issues associated with the Great Recession of 2008 began to constrain all federal spending.

Difficulties in achieving the Prague Capability Commitments led NATO defense ministers, at their Istanbul meeting in June 2006, to finally declare that “Allies through the comprehensive political guidance have committed to endeavor to meet the 2 percent devoted to defense spending.” Subsequently, just prior to the November 2006 Riga summit, Victoria Nuland, U.S. permanent representative to NATO, openly identified the 2 percent metric as the “unofficial floor” on defense spending in NATO. The final communique of the Riga summit, however, included only a diluted “we encourage nations whose defense spending is declining to halt that decline and to aim to increase defense spending in real terms.”

Though it continued to be bandied about in NATO circles, nothing further was officially heard of the 2 percent criterion until the NATO Wales summit in 2014. The commitment was confirmed at the 2016 Warsaw summit and again, most recently, at the 2018 Brussels summit where the allies agreed to “reaffirm our unwavering commitment to all aspects of the Defence Investment Pledge agreed at the 2014 Wales summit, and to submit credible national plans on its implementation, including the spending guidelines for 2024, planned capabilities, and contributions.” The enshrinement of the 2 percent icon was complete.

Defense choices

NATO member states remain sovereign nations and as such are free to determine just how much they are going to spend on defense and how they are going to spend it. Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty simply requires NATO members “to maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.” How much they actually spend on defense and how they spend it depends on a host of factors in addition to any Alliance commitments. The willingness to spend on defense will depend in the first instance on how they perceive threats to their sovereignty, which in turn will depend upon their immediate geographical neighborhood and their relationship with their neighbors. Greece and Turkey, for example, have long been identified as major contributors to NATO, but their relatively high defense budgets, at least in the past, have had more to do with their acrimonious relationship with each other than with NATO’s strategic requirements.

A nation’s willingness to spend on defense has to be balanced against its ability to do so. This depends on its economic capacity and performance, and critically, on the state of its public finances, especially its debt situation. The global financial crisis of 2008 and consequent long period of recession and slow growth left many NATO members with large fiscal deficits and high levels of public debt leading some, including the U.S., to reduce defense spending. Ironically, countries that experienced negative economic growth but cut defense expenditures at a slower rate actually showed an increase in the share of GDP going to defense. Such is the arithmetic of looking at defense expenditures in terms of GDP share.

Membership in an alliance will also influence the willingness of nations to spend on defense. The economic theory of alliances suggests that once alliance capacity is provided to meet a common threat, nations, particularly the smaller ones, have an incentive to reduce defense expenditures and “free-ride” on the others. As a result, the alliance as a whole ends up with a resource shortfall.

In addition to low spending levels, the reality is that aggregate total spending by European members of NATO is spread over 28 countries, each of which retains its own defense ministry, military headquarters, training establishments, logistics systems and so on. This fragmentation represents a huge fixed cost, severely limiting the resources available for creating real Alliance military capability and denying the Alliance the full benefits of economies of scale that would otherwise be available from a more integrated structure. This is graphically illustrated by the fact that while the U.S. has about 1.4 million military personnel, NATO Europe has over 1.8 million, but is able to produce only a small fraction of the capability produced by U.S. forces.

A smart way out?

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, NATO defense budgets declined dramatically and continued to do so until 2014. To halt the decline in military capability implied by declining budgets, NATO’s secretary-general in 2011 introduced Smart Defence, an initiative later endorsed by member countries at the Chicago summit in 2012. Smart Defence attempted to draw member countries and other partners into collaborative procurement of equipment, integration of force structures and specialization in military roles, all of which were aimed at overcoming the fragmentation of European defense efforts and squeezing more military capability out of declining budgets. More fundamentally, it was an attempt to engender an era of enhanced cooperation where multinational collaboration was to become the Alliance’s routine operating procedure.

Smart Defence has an appealing logic. However, we have no empirical proof that collaboration and cooperation can really provide more capability. Indeed, there are reasons to believe that it will be much less than anticipated. For one thing, it gives rise to a whole new set of international sharing issues. Thus, nations might avoid collaboration for fear of being dragged into conflicts just because they share a particular capacity with other countries. Or, on the other side of the coin, they might fear that partners sharing a capacity will not be there when needed. Collaborative procurement may also be opposed if rationalization of defense production impacts negatively on domestic industry and employment. In the end, Smart Defence might not increase capabilities at all, given that collaboration itself incurs costs, particularly in terms of coordination and communication.

A better view

The great appeal of the 2 percent target is its simplicity. By reducing complex defense expenditure issues to a single, seemingly plausible number, it makes it possible to establish measurable performance goals and thus to identify which nations are meeting those goals and which are not. In that sense, it can be a powerful marker of Alliance cohesion and determination. It can also be a persuasive political tool for pressuring member states to pull their weight. The problem is that it is a completely arbitrary number, unrelated in any meaningful way to actual capability contributions. Its focus is on total spending rather than on how defense monies are actually spent. More critically, it avoids any concern for the relative ability of different member states to convert defense spending into real military capability.

The challenge to NATO, then, if the burden-sharing debate is to become more consequential than a perpetual row over money, is to come up with metrics that focus on capability contributions. To be acceptable, such measures will have to share the virtue of simplicity that has made the 2 percent target so memorable and so politically acceptable. But the difficulty in focusing on defense capabilities, or defense outputs, is that ultimate measures of success are generally immeasurable or completely incongruous: the absence of war is no indicator that deterrence is working; winning a war is an indicator that it has failed. As a result, proxy indicators have to be found that relate as closely as possible to the things that NATO is trying to accomplish.

What NATO is attempting to achieve is most specifically outlined in its Strategic Concept. This document presents NATO’s view of the current security environment and indicates how it intends to respond to challenges arising from that environment. The most recent Strategic Concept, approved at the Lisbon summit of 2010, identified collective defense, crisis management and cooperative security as the Alliance’s essential tasks. Collective defense relates to the traditional North Atlantic Treaty Article 5 commitment that an attack on one member is an attack on all. Crisis management involves the application of NATO political and military instruments to resolving any crisis that might affect Euro-Atlantic security, including crises arising outside of the NATO geographical area. Cooperative security involves NATO efforts to actively engage in international security affairs, primarily through security partnerships with other nations and organizations throughout the wider world.

The latter two tasks arose out of the security environment that existed between 1989 and 2014, where the threat from the Soviet Union dissipated and NATO found itself becoming more of a global security actor. However, the security situation has changed considerably since 2010, suggesting perhaps that it is time for a new strategic concept. In any case, it is clear that Russia has re-emerged as the primary threat and NATO’s emphasis has accordingly shifted back to the first of its core tasks. And, as in the past, NATO’s response is sharply focused on a deterrence strategy, one rooted in demonstrable and convincing military capabilities.

How NATO attempts to go about acquiring those capabilities is the clue to devising better, more meaningful measures of burden sharing. And how it does so is the focus of its Defence Planning Process. This formal, five-step process begins by defining the capabilities required to meet the Alliance’s agreed strategic objectives. Through consultation, it then attempts to apportion capability targets to member countries based on each nation’s own sovereign defense plans and on the basis of a “fair” share of the overall requirements. How fair is determined is, for understandable reasons, not publicized, but after more than 70 years of NATO evolution it has to be assumed that NATO planners have become highly skilled in managing internal political pressures to arrive at pragmatic and workable measures.

The final stage in the planning process is a detailed assessment of how well members are meeting NATO’s capability targets. At this stage, NATO produces a performance report consisting of 11 metrics for each nation. Two of these metrics represent traditional expenditure inputs, including the much-noted total defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP, and the share of these expenditures allocated to new equipment and research and development, which is the second measure highlighted in the Wales summit pledge. The remaining nine metrics consist of a mixture of quantitative and qualitative output measures, including current force deployment on NATO missions, as well as deployability and sustainability measures. These measures are then compared to existing NATO targets, such as the requirement that land forces should be at least 50 percent deployable — 10 percent deployable on a sustained basis — as agreed by defense ministers in 2008. Finally, the 11 metrics are ranked in comparison with other members.

This type of report better measures capability outputs and offers a more complete picture of actual contributions to the Alliance. Unfortunately, only Denmark has made its results publicly available; other nations, undoubtedly with good reason, treat them as classified information. This is unfortunate because such measures have real potential to shift the focus of the burden-sharing debate away from the 2 percent obsession and toward the things that really matter to the business of the Alliance.

The use of these metrics, though they are comprehensive, succinct and clear, is somewhat inhibited by the fact that there are 11 of them and they thus lack the uncluttered simplicity of the 2 percent criterion that dominates the burden-sharing debate. Consolidating these 11 measures into some sort of report card with rankings pertaining to funding, available forces and current activities — or cash, capabilities and commitment, as NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg recently put it — could change that.

Apart from the specifics, it is significant that the vocabulary of the burden-sharing debate appears to be changing for the better. This emerged strikingly in the recent introduction of NATO’s European Readiness Initiative. To fill a perceived gap in its response capabilities in the early stages of a European crisis between existing “very high readiness” forces and “initial follow-on” forces, NATO defense ministers at their June 2018 Brussels meeting, again at the urging of the U.S. secretary of defense, endorsed the “Four Thirties” plan, which calls for a force of 30 battalions, 30 squadrons of combat aircraft and 30 ships to be ready to use in 30 days. The terms of this declaration strongly suggest that NATO is now prepared to publicly discuss its plans in terms of concrete warfighting capabilities measured in deployable combat power. Apart from its “30s” symmetry, somewhat evocative of the 2 percent sloganeering, it does compel European governments to focus on force readiness. Importantly, it lays bare the critical need for expedited political decision-making in potential crisis situations and pinpoints the immediate need to build an effective command structure and to prepare the physical and procedural capacity to mobilize forces across national borders.

Performance and patience

NATO burden sharing has always been about more than money. If it were otherwise, the Alliance would surely have disappeared long ago. Expenditure equity is just too visible to be allowed to get too far out of line, but a shift of focus toward what these expenditures actually achieve can move the debate to more relevant considerations and reduce the potential for simplistic measures distracting the Alliance from its proper business of building capability.

In a voluntary alliance, where each member is free to determine what it spends on defense and how it spends it, burden-sharing issues are inevitable. Paradoxically, it is this very freedom that is NATO’s strength. The institutions, bureaucracy, organizational structures, command and control arrangements, planning processes and consultation mechanisms that have evolved over the past seven decades to manage this diversity, and which would be impossible to replicate, are the glue of the Alliance and the ultimate source of its durability.

That being said, if NATO’s next major celebration is to be its centenary, 30 years hence, then getting there is going to require proof from European NATO that it is seriously working toward rebalancing burden sharing by investing in useable capabilities. From the U.S., it is going to require patience and the discipline to refrain from overplaying its hand.

Comments are closed.