Promoting collaboration between two of the world’s most powerful organizations

By Dr. Dinos Anthony Kerigan-Kyrou Emerging Security Challenges Working Group

The European Union and NATO are quite different organizations. The EU, previously the European Community, and before that, the European Coal and Steel Community, was established in 1958 with Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands as “the Original Six.” Since then, successive treaties have grown the EU to 28 states and greatly enhanced cooperation and integration in business, free movement of goods and services, economic policy and lately, foreign and defense policy.

The EU’s European External Action Service (EEAS) was launched in 2010. EEAS has extensive foreign policy implementation capabilities combined with crisis management, intelligence gathering and, increasingly, military proficiency. EEAS is headed by the EU High Representative Federica Mogherini. Its Common Foreign and Security Policy is decided by EU foreign ministers representing each member state at the Foreign Affairs Council, chaired by Mogherini.

NATO also has grown — now 28 states from the original 12 that signed the Washington Treaty in 1949. To this day, the central element of the treaty is Article 5 — an armed attack on one member is considered an attack on all members. It provides for collective defense, deterrence and response. There is a significant overlap between the EU and NATO. It is easier to point out who is not in both organizations. With the exception of the Republic of Cyprus, every member of the EU is a member of NATO or Partnership for Peace (PfP).

Cyprus wishes to join PfP. EU members Sweden, Finland, Ireland and Malta are all in PfP. NATO members Canada and the U.S. are clearly not in the EU, and Albania and Turkey aspire to join the EU. Indeed, along with Greece, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, but its EU ambitions have yet to be fulfilled more than six decades after joining the Alliance. NATO member Norway decided not to join the EU but follows most EU laws and participates in the EU’s common passport region called the Schengen Zone. Moreover, Norway participates in many aspects of EU defense.

History of Cooperation

Until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the assumption was clear: Europe’s defense was conducted by NATO. Europe’s early efforts at a separate non-NATO defense collapsed. The European Defence Community, planned as early as 1948, fell apart because of France’s fears over sovereignty. The military replacement, the Western European Union (WEU), proved incapable of dealing with Yugoslavia’s collapse in 1991. This was an emergency in Europe’s backyard and one that NATO was not supposed to handle. In other words, through NATO was considered an unsuitable vehicle to fulfill this foreign policy and military objective, the WEU failed.

It was not until 2002 that the EU and NATO formed a set of arrangements whereby the EU could access NATO assets and capabilities to conduct crisis management operations and share secure information. This set of arrangements within the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), in which the EU could operate when NATO declined to do so, became known as the “Berlin Plus” agreements. There have been only two operations under Berlin Plus, both successful. The first, in 2003, was Operation Concordia in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, where the EU took over NATO’s Operation Allied Harmony. The ongoing European Union Force (EUFOR) operation Althea, the EU military deployment in Bosnia and Herzegovina to oversee implementation of the 1994 Dayton Agreement, has been in place since 2004.

It was not until 2002 that the EU and NATO formed a set of arrangements whereby the EU could access NATO assets and capabilities to conduct crisis management operations and share secure information. This set of arrangements within the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), in which the EU could operate when NATO declined to do so, became known as the “Berlin Plus” agreements. There have been only two operations under Berlin Plus, both successful. The first, in 2003, was Operation Concordia in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, where the EU took over NATO’s Operation Allied Harmony. The ongoing European Union Force (EUFOR) operation Althea, the EU military deployment in Bosnia and Herzegovina to oversee implementation of the 1994 Dayton Agreement, has been in place since 2004.

Different experiences, different capabilities

For more than six decades NATO has established a well-organized and well-executed command, training and logistical structure. But NATO is limited in its aims and objectives. One could argue that the primary purpose of NATO is to deter, and if necessary, respond if Russia attacked a member. And yet, the first and only time Article 5 has been invoked was as a result of something that NATO was totally unprepared or designed for — an asymmetric suicide attack by al-Qaida on New York and Washington, D.C., on September 11, 2001. In turn, NATO led the International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan for the next 13 years. ISAF was an out-of-area operation that would have been unthinkable on September 10, 2001. Mindful of these changing challenges, in her NATO commissioned report on the future of the Alliance, “NATO 2020: Assured Security: Dynamic Engagement,” former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright addressed “new” security issues, saying that “the boundary between military and non-military threats is becoming blurred.” Such threats include energy security, cyber security and asymmetric terrorist attacks. One can add to this a multitude of emerging security challenges and threats that cross the divide between the military and the civilian spheres — climate change and extreme weather events such as hurricanes, floods and fires; food and water security; the resilience of critical infrastructure such as electricity, water treatment and transport; and pandemics and the spread of diseases.

And we are at the start of a technology revolution enabling access to incredible capabilities. Unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), unmanned ground vehicles, 3D printing, nanotechnology, the development of cyber-physical systems, “Big Data,” and the progression of what has become known as “Internet of Things” will revolutionize industry and empower individuals. But technology is neutral. It can be used for great good, for example by medical professionals pioneering new forms of robotic surgery, or great harm, such as ISIS using a drone to commit another atrocity. It could be argued that NATO, as a traditional military organization, has a substantial challenge addressing these developing and overlapping areas. Huge progress has been made, including the establishment of NATO’s Emerging Security Challenges Division, headed by Assistant Deputy Secretary-General Dr. Jamie Shea. But the extent to which NATO will proceed in areas considered “nonmilitary” remains to be seen. Indeed, some NATO members see such progression as crossing a “military boundary” that would make them highly uncomfortable.

While NATO may be constrained with moving beyond such a boundary, the EU faces quite different challenges. Transport, critical infrastructure, the economy, health, emergency planning, cyber security, combating organized crime, preventing human trafficking, and border protection are examples where the EU has made substantial progress. Moreover, as the world’s second biggest economy, the EU has unrivaled economic power to pursue foreign policy goals. Indeed, sanctions aimed at Iran, North Korea or Russia are of little value without the full acquiescence and engagement of the EU.

EU defense deficiencies

Despite recent economic recessions, the EU and the U.S. are by far the most important global economies. The EU is of vast and increasing foreign policy importance. But perhaps surprisingly, in terms of military defense, the EU is somewhat uncoordinated. The EU consists of 28 separate defense policies. Eighty percent of EU procurement is made domestically, resulting in a huge loss of cost and technological efficiencies. The EU has 1.6 million armed personnel — even more than the U.S. — but 70 percent cannot be deployed. EU states have just 42 air-to-air refueling aircraft, consisting of 12 different types. By comparison, the U.S. has 550 refueling aircraft of only four types. The EU has 30 different helicopter training programs, 15 different armored personnel carrier programs, five types of tanks and four kinds of multirole aircraft. Examples of this inefficiency and duplication have been highlighted by Graham Muir of the European Defence Agency (EDA). Indeed, such examples are so numerous that they would fill this entire journal, and the EDA is doing excellent work to address this issue. But the EDA faces tough national resistance based on the myth that EU states have “sovereignty” over national defense. This myth was brutally exposed by the 2011 military intervention in Libya to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973.

Libya was indeed the first occasion when the U.S. was content to let EU states lead a military intervention. However, Washington was frustrated that Europeans, despite 20 years of defense integration and investments of 180 billion euros annually on defense (more than China and Russia combined) could not do basic tasks such as targeting and intelligence gathering. Indeed, after just a few days of operations, the Europeans ran out of precision guided munitions. Moammar Gadhafi’s Libya, a country with a tiny defense budget and a barely functioning army, could not be defeated without significant U.S. support. In a speech in the Netherlands in January 2013, Dr. Shea noted that U.S. drones, missiles, surveillance and air-to-air refueling were absolutely vital. Indeed, the EDA admits publicly that Europe continues to lack key enablers such as air-to-air refueling, intelligence, satellite communications, surveillance and reconnaissance.

This is the “European Enigma”: It’s an economic superpower that rivals the U.S. and possesses a high representative who is U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s first phone call when he seeks allied opinion. The EEAS stations diplomats in nearly every country of the world. The Continent holds seats at the G7 and G20, and plays one of the most important roles on the world stage. But it is a Europe that is unable to undertake a military operation without U.S. support against a state with a barely functioning army.

EU strengths

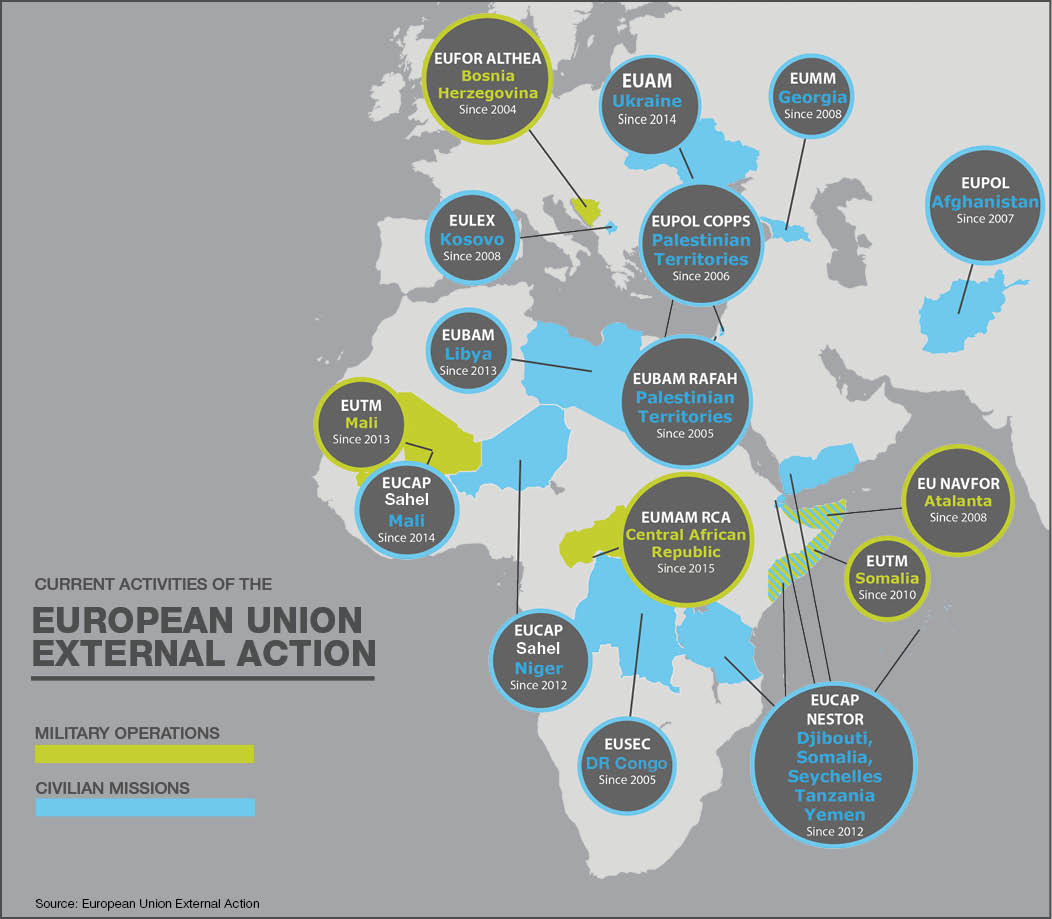

While the EU is incapable of fighting a traditional war against a state, its military capabilities in new and emerging situations should not be underestimated. EEAS increasingly operates highly effective civilian and military missions across the world. In addition to EU Althea in Bosnia, these have included Operation Artemis and EUFOR operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Chad. Current EU military operations include the EU Naval Force for counterpiracy in Somalia, EU Naval Force Atalanta, and the EU Training Mission in Mali in support of counterterrorism. Nestor, an EU capacity-building effort, supports the maritime capacities of five countries in the Horn of Africa and the Western Indian Ocean.

The EU sponsors 11 ongoing and nine completed civilian training missions, including the EU Police Mission to train law enforcement in Afghanistan. The EU has established 19 rapid deployment battle groups consisting of two to six countries each, the largest being the Nordic battle group comprising Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Norway. Special forces European battlegroups are another example of the EU’s developing role in nontraditional warfare. Moreover, with the Europol European Cybercrime Centre, the EU has developed an unparalleled ability to tackle cyber-related crime such as fraud, intellectual property theft, serious organized crime and terrorism. Not only does Europol consist of EU members, it also has operational agreements with and seconded officers from 12 other states, including the U.S., Norway and Australia. Europol is uniquely able to bring together expertise and data from 40 countries.

It could be argued that while the EU is unready to fight a traditional war, it is, conversely, ideally placed to engage in crisis management, upholding and supporting UN mandates, special forces operations, cyber security, and military, civilian and police training. A March 2015 trip the author made to Brussels to consult with EEAS officials raised some interesting points: The EU is arguably better in dealing with issues, usually civilian related, that cut across military and nonmilitary boundaries. It is perfectly logical that an organization such as the EU — which is not a military organization but offers a military component— possesses a much wider toolbox than a purely military organization.

Not only is there potential for NATO and the EU to work together, but there may indeed be a perfect synergy. NATO could take the lead in dealing with traditional military threats, such as an Article 5 situation or a direct military engagement against a foreign power — something that European states are unable to do. But in nontraditional areas of overlap between the military and the nonmilitary, the EU could take the lead in helping NATO.

Another area of potential cooperation could be to combat what has become known as “hybrid war,” perhaps best exemplified by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Hybrid war consists of deniability, subterfuge and propaganda. Cyber is a perfect element of a hybrid war because it is deniable and can have far-reaching ramifications. For example, a cyber attack on a water treatment facility could have catastrophic consequences but is also deniable. Likewise, the cutting of gas supplies or raising its cost exorbitantly because the target has no other source of energy could be blamed on “lack of supply” or “economic” reasons.

Russia doesn’t appear to be the only entity engaged in hybrid war. ISIS, although a nonstate actor, is another example of an advisory that has adopted “hybrid” tactics such as the sophisticated use of social media to attempt to influence EU populations.

And it is not just Ukraine that has experienced Russia’s preference for hybrid war. An Estonian government officer was kidnapped by Russia in September 2014. Russia claimed the officer, Aston Kohver, was on its side of the border when he was illegally detained. However, if Kohver was on the Estonian side, one could argue that the kidnapping constituted a Russian invasion of a NATO state. But again, the situation included deniability, subterfuge, contradiction and confusion — all elements of hybrid warfare.

In March 2014, Gvidas Venckaitis, attaché at the Lithuanian Embassy in London said to the author: “Russian propaganda is another emerging threat which has to be addressed at both NATO and the EU level. Russian state-controlled and sponsored international ‘media channels’ such as RT [Russia Today] or Sputnik need to be clearly identified as propaganda. The question of licensing such ‘media’ should be ultimately posed. … There should be more discussions on … EU media regulatory framework, for example the Audiovisual Media Services Directive. We are pleased to note that the EU External Action Service is eager to play a greater role in this respect.”

Lithuania is an EU and NATO state that has been pushing a robust response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine via both the EU and NATO. Venckaitis suggested the EU and NATO work together to address emerging threats such as cyber security, energy security and hybrid war: “First and foremost, we must not forget about the conventional security threats that unfortunately continue to exist. Russia names NATO as an adversary bloc in its military doctrine and systematically increases the expenditure of military procurement and modernization of warfare. In this light, NATO allies should act accordingly. First of all, the member states have to reach the agreed 2 percent of GDP expenditure on defense. Deterrence of a potential aggressor is of key importance in these geopolitical circumstances.”

Communication

The North Atlantic Council (NAC) is NATO’s principal decision-making body and meets with the EU’s Political and Security Committee (PSC), formally or informally. Formal meetings are challenging because Cyprus and Turkey have no diplomatic relations at all. Because of this, PSC and NAC formal meetings are very rare. Since 2011 the PSC and NAC have had three informal meetings, one about Libya and two others in 2014 about Ukraine. Regarding Ukraine, NATO focused more on military events and the EU on civilian safety.

Lithuania is keen to develop and expand the work of the PAC/NSC and believes meetings have been beneficial. Venckaitis stated: “Security challenges that the European countries are facing today demand as much information sharing between NATO and the EU as possible. Lately, we have observed a significantly growing number of staff-to-staff talks between NAC and PSC. … Regular meetings between NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg and EU High Representative Federica Mogherini also bear witness to the closer cooperation between NATO and the EU.”

Poland stresses a similar message. Retired Navy Capt Piotr Gawliczek of the Polish National Defence University interviewed several leading military and political figures on behalf of the author. Capt. Gawliczek said: “Poland wants to make the EU the real subject of international security. Polish officials claim that the EU has to have a real-term security strategy and underline that the EU should take advantage of the opportunity created by this year’s CSDP summit in June to start working on it. Poland argues that changes in the European security environment, especially the qualitative change on the eastern flank, require a strategic adjustment of Euro-Atlantic structures — not just NATO’s but also the EU’s.”

In regard to NATO and the EU working together, Capt. Gawliczek stated: “From the Polish point of view, it is essential to achieve CSDP growth in harmony with NATO without challenging NATO’s role in the European security system or the U.S. military’s position in Europe. Therefore, Polish diplomacy acts in various forums — the Visegrad Group, or V4, and the Weimar Triangle — to bolster the CSDP. Through the Weimar Triangle, Poland is trying to enhance key EU defense capabilities, such as improving EU-NATO relations, establishing permanent civilian-military planning and command structures, and developing EU battlegroups and their defense capabilities. The V4 Battle Group will begin operations in 2016 and remains the most important common project in the field of defense.”

Like Lithuania, Poland therefore believes strongly that it is not a question of “EU or NATO” but “EU and NATO.”

A European army?

Article 41 (7) of the EU’s 2007 Treaty of Lisbon states that when an EU country is the target of armed aggression on its territory, other EU member states shall aid and assist by any means possible. In other words, the EU has its own Article 5. Nevertheless, the EU is incapable of a collective defense against an aggressor country in any conventional sense, short of threatening and ultimately using the nuclear capabilities of the United Kingdom and/or France — the EU’s nuclear powers. Short of that dramatic escalation, Article 41 (7) is ineffective. This may be why European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker stated in March 2015 that “a common army among the Europeans would convey to Russia that we are serious about defending the values of the European Union.”

Indeed, this process is starting, albeit gradually, with the development of the EU battlegroups — rapid deployment of troops based on an infantry battalion or armored regiment. Operation Artemis, located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and intended to stabilize the area during the 2003 Ituri conflict, was the first test of the concept and proved highly successful. NATO Secretary-General Stoltenberg said that he welcomed increased European investment in defense, but “it’s important to avoid duplication, and I urge Europe to make sure that everything they do is complementary to the NATO alliance.” U.S. Air Force Gen. Philip Breedlove, NATO’s supreme commander in Europe, agrees that NATO “would like to avoid … any duplication because we need to smartly invest,” he said at a NATO news conference in March 2015. In short, the NATO position is: Support is welcome, but there is enough replication and duplication.

Professor Trevor Salmon of the College of Europe reinforces this perspective. Prof. Salmon reminded the author that the U.S. Bartholomew Memorandum of 1991 stated that Europe acting within NATO parameters was welcome, but was dubious of Europe acting without NATO. Salmon adds that the notion of a European defense may ultimately question the leadership of the United States. Salmon points to President George H.W. Bush’s visit to Rome in 1991 when he asked if Europeans wanted the U.S. to remain committed. Few today question U.S. commitment to Europe.

Former Director General of the Council of the European Union Sir William Nicoll takes a firm line on the EU’s role as a military power. Nicoll told the author: “I do not know why the EU thinks that it needs a military capacity. Its decisional structure is demonstrably not suited to the prompt and emergency actions which a military capability depends upon. This suggests that the EU should subcontract its military interests to NATO and not seek to inject its bureaucratic systems into NATO’s missions. … I am far more concerned about the current tensions between NATO partners and Russia.”

Dr. Shea points to the possibility of a “New Transatlantic Bargain” that is not the “in together out together” philosophy. Libya is a case in point: Only eight allies participated, with some declining to participate even though they had the capabilities. Sweden was involved in the air campaign despite being outside NATO. In the future, we may have more coalitions in which all 28 NATO states pay for a multinational structure that not all of them use at any one time. Each would see a collective benefit.

NATO and the EU will continue to work together. Both organizations bring separate attributes to one another. However, perhaps we too should start to consider a “NATO/EU Hybrid Response.” How can NATO and the EU bring the best attributes of one another to defeat adversaries, be they states or, increasingly, nonstate violent actors such as ISIS? How do we in NATO and the EU perhaps stop looking at what prevents the two organizations from collaborating and instead focus on what empowers the two organizations to collaborate even more? A proactive, adaptable hybrid response that addressees new and traditional challenges with military and nonmilitary attributes perhaps needs to be considered. As Madeline Albright said, the boundary between military and nonmilitary threats is indeed blurred. It will remain so for many years to come.

Comments are closed.