Interrupting the Money Flow Can Paralyze Terror Groups

By Ivica Simonovski, Ph.D., Financial Intelligence Officeof the Republic of North Macedonia. Photos by The Associated Press

One of the key elements in the fight against terrorism is tackling the financing. Identifying and cutting off financial flows will reduce the capacity of terrorist groups to carry out attacks, increase their operating costs, and bring risk and uncertainty to their operations. In such circumstances, they will often take actions that expose their operations. Therefore, the fight against terrorism financing should be extensive and include every affected stakeholder in a society.

Money is a prerequisite for the realization of all terrorist activities and is often described as an “energy source” or a “bloodstream” of terror organizations. Funds are needed for the development of an organizational infrastructure, recruitment, propaganda, training, planning and for executing attacks. This explains the need for long-term and stable sources of funding. Terrorist organizations often obtain funds by engaging in legal and illegal activities where they operate. The funding schemes can be short term and long term and are typically supported by international backers and by countries that sponsor terrorist organizations. Funds can be generated in areas the terrorists control, from internal and external sources and from legal and illegal activities. Terrorist organizations also need weapons, ammunition and technical equipment, which usually cannot be manufactured or purchased in the territory they control. The procurement of such resources requires complex schemes involving many individuals, including collaborators who support the process. Terrorists often employ intermediaries, known as “money mules,” who use phony accounts to procure these necessary resources.

The problem gets more complex when trying to trace how these resources enter a territory controlled by a terrorist organization. The Islamic State, also known as Daesh, provides a good example of how difficult it can be to track these resources. The organization declared a caliphate in parts of Iraq and Syria. The territory is rich in oil, so one of Daesh’s main sources of stable and long-term funding was from the sale of oil. These funds were used to pay members and to buy uniforms, weapons, ammunition and other needs. The money raises many questions that require in-depth research to answer. How was the oil sold? Was it sold within Daesh-controlled territory or was it exported? Who bought the oil and how was the money transferred? How were weapons purchased and from whom? How were the weapons transported? And what were the main routes for these activities? The answers to these questions, complemented by the monitoring of cash flows, can help in developing a strategic analysis that can provide a set of measures and actions that need to be taken at the national, regional and global levels to successfully counter terror financing.

Monitoring the money flow presents another problem. Large amounts of money are needed to fund terrorist activities, especially weapons purchases. The financial system in the area controlled by Daesh was not functional, so it is assumed that the financial systems in neighboring territories and states were used. In this respect, the increased frequency of transactions from/to financial institutions should be subjected to an in-depth analysis by the departments responsible for preventing money laundering and terror financing. There is a need for a strategic and tactical analysis that can result in a set of measures to help identify suspicious activities.

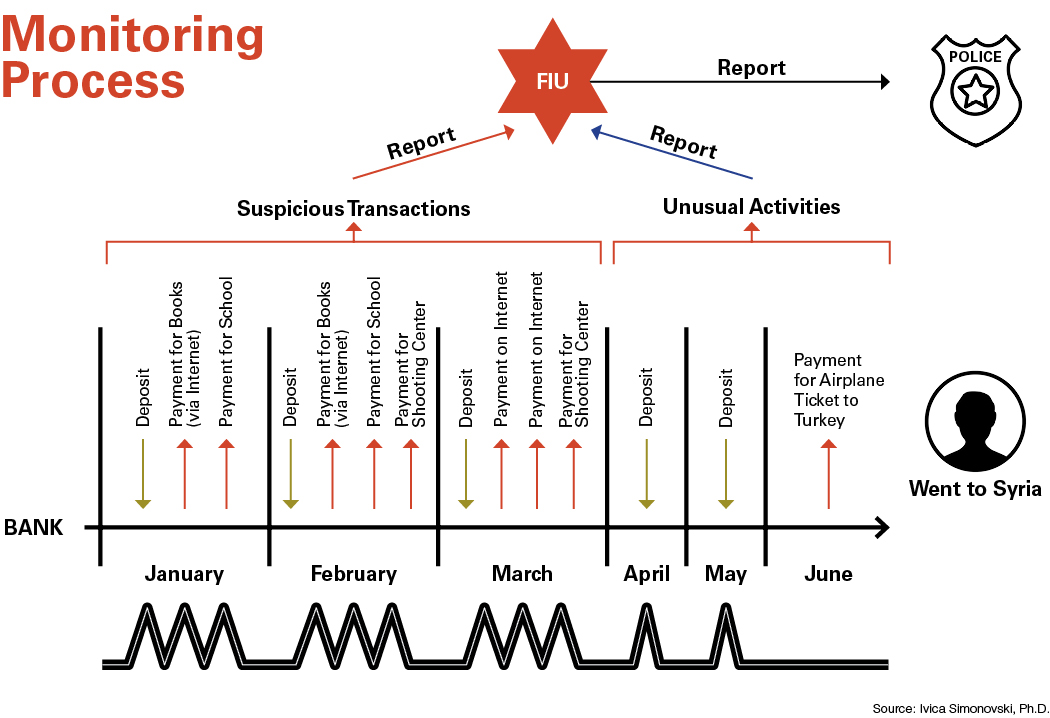

The fight against terror is adjusting to the new arrivals on the scene: terror cells, foreign fighters and lone wolves. Unlike terrorist organizations, these new actors can have different goals and a different phenomenology. Consequently, their needs for financial resources are different. These actors are decentralized and act independently in all stages, including the financing of their activities. As an illustration, 57 percent of jihadist cells that have carried out terrorist attacks in Europe in the past 15 years have funded their activities, including the execution of attacks, from legal sources such as salaries, savings, loans, family help, personal funds and even their own businesses. This type of financing does not cause suspicion among the financial and nonfinancial institutions that are required to report suspected terror financing and money laundering.

These institutions are obligated by law to implement a customer due-diligence procedure and identify suspicious or unusual transactions and clients. If they identify such transactions and clients, they are obliged to submit data to a financial intelligence unit (FIU) for analysis. Here, the client identification procedure is particularly important. It is implemented before a business relationship is established to obtain the potential client’s financial status, intentions, location and criminal past — generally, the risk a financial institution could incur if it does business with the applicant.

The establishment of a system to prevent money laundering and terror financing is crucial in identifying the financial flows that fund terrorism. As mentioned, a large percentage of the financing of jihadist terror cells has been through legal sources. Consequently, questions arise about the steps financial institutions have taken to prevent money laundering and terror financing, and whether they have identified suspicious or unusual transactions and notified an FIU.

Core functions

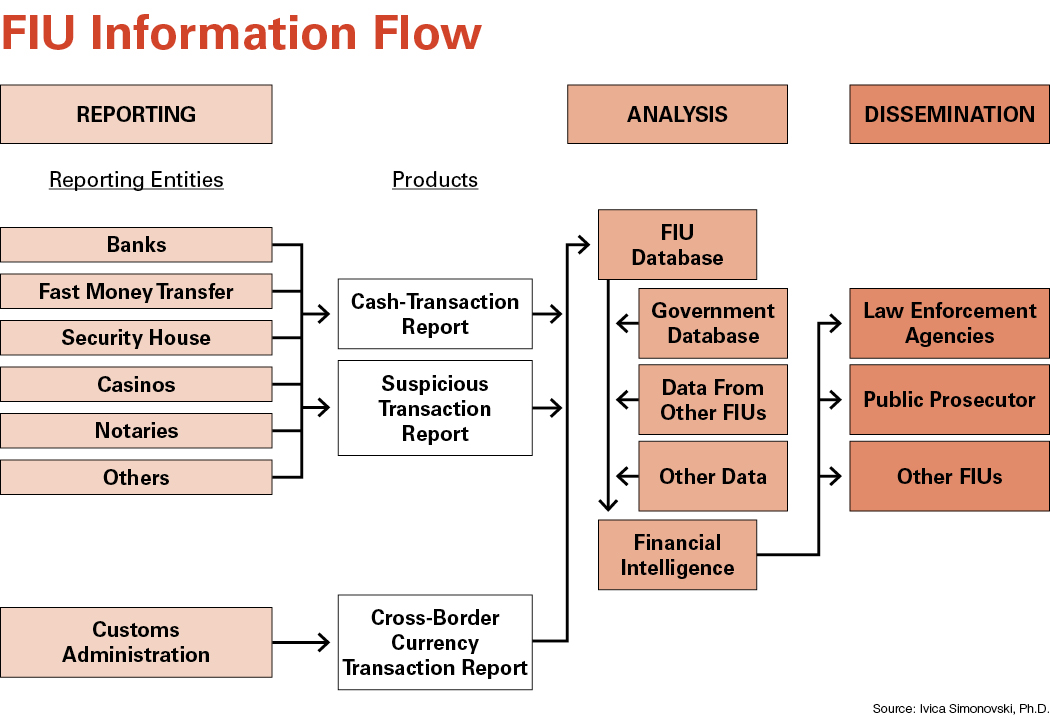

The definition of an FIU — adopted in 1996 by the Egmont Group, a network of FIUs — formalized three core functions: the receiving, analyzing and disseminating of information, data and documents about money laundering, terror financing and other criminal offenses that generate proceeds. According to the definition, an FIU is a “central, national agency responsible for receiving, (and as permitted, requesting), analyzing and disseminating to the competent authorities, disclosures of financial information: (i) concerning suspected proceeds of crime and potential financing of terrorism, or (ii) required by national legislation or regulation, in order to combat money laundering and terrorism financing.” This includes the revised Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations of 2003. According to Recommendation 26, “Countries should establish a FIU that serves as a national centre for the receiving (and, as permitted, requesting), analysis and dissemination of STR [suspicious transaction report] and other information regarding potential money laundering or terrorist financing.” The three core functions of the FIU are also mentioned in international conventions (the Palermo Convention and United Nations Convention against Corruption). Initially, the three core functions of the FIU were focused only on money laundering. But the revised FATF recommendations of 2003 expanded FIU functions to preventing terror financing. With the revised FATF recommendations of 2012, the functions were further expanded to include other predicate offenses that generate proceeds.

Analyzing suspicious transactions

By definition, the FIU is the central agency in the system for preventing money laundering and terror financing. After receiving and analyzing data on suspicious transactions and activities, the information is disseminated to the relevant authorities for further investigation. The FIU may receive suspicious transaction reports from the obligated entities, from data provided by other FIUs, or from data generated by other state bodies.

The number of reports can vary, and the volume may be too large for an FIU to analyze in a timely manner. In that case, the FIU can prioritize the reports based on the degree of their suspicion. The reports that are not analyzed can be stored in a database that can provide strategic analysis or be linked to previous cases. The analytical work is a core function of almost all FIUs. For successful analytical work, the FIU should have access to a variety of databases and information sources. The analysis carried out by the FIU can be tactical and strategic.

Tactical analysis

The tactical analysis of an STR is closely related to the quantity and quality of the collected data. Therefore, the FIU should have timely access to the data. An analyst searches for a connection between suspicious transactions, people involved in the deal, criminal groups or terrorist organizations, and predicate crimes. Knowledge, access to relevant databases, and access to publicly available information are required to process the STR. Necessary databases include:

- FIU’s database

As previously mentioned, the obligated entities must submit STRs, transactions over 15,000 euros and related transactions in the amount of 15,000 euros and more. The FIU’s internal database includes all data and requests submitted by competent authorities and foreign FIUs. In addition, a country’s customs administration is obliged to report to the FIU the entering and exiting of money or physically transferable assets for payment over 10,000 euros. The data, as well as data from previous analyses, should be stored in the FIU’s internal database. - Databases of state institutions

The dynamics and speed of money laundering and terror financing require timely detection and prevention. The FIU needs direct and quick access to databases of other relevant institutions through which it will provide quality and necessary data. For that purpose, the FIU should have electronic access to databases that will be regulated by law or a memorandum between the FIU and other institutions. Any changes in the databases should be delivered in real time to the FIU via web services and an interoperability system. Generally, FIUs need electronic access to these databases: - Criminal records

- Birth certificates

- Motor vehicles

- Watercraft

- Aircraft

- Bank accounts

- Employment

- Real estate

- Businesses

- Taxes

- Securities

- Others as needed for financial analysis

- Publicly available databases

Access to publicly available databases, media web portals or social networks is generally free, but others require payment. The most commonly used include: - World Check

- Data from public media

- Data from internet and social networks

- Dow Jones

- Lists of terrorists and terrorist organizations (United Nations, European Union, Office of Foreign Assets Control)

- Dun & Bradstreet

All of the above are necessary for a timely and expert financial analysis. The data is used to profile people, determine their work history, how they acquired their material possessions, the basis and logic for the financial transactions they carry out, whether the transactions are suspicious, and whether to monitor future activities. The outcome of the financial analysis should either dispel any suspicion or result in the dissemination of data to investigating authorities for further analysis.

Strategic analysis

Apart from the tactical analysis of the finances of a money laundering or terror financing case, a strategic analysis focuses on determining whether an event happened or will happen during a certain period. Strategic analysis will help the FIU prepare strategic plans for future work and focus, i.e., whether certain customers, geographical areas, sectors, products and activities should be subject to further analysis and appropriate measures and actions to overcome, eliminate or prevent them. To that end, all available FIU data are used.

Strategic analysis can help identify an increase or reduction of transactions from and to risky regions and countries where terrorists operate or where armed conflicts are occurring, and from and to the regions and states around them. An example of a strategic analysis can be the increased frequency of transactions from and to border towns on the Turkish-Syrian border (Diyarbakir, Gaziantep, Adana, etc.). The object of the analysis will be to determine the cause and frequency of transactions, the sector used (bank, money transfer providers), the customers and end users of the funds, and their possible connection with terrorist activities. The strategic analysis should produce the information needed for financial institutions and state authorities to determine the ultimate purpose of transactions from and to that region. Based on the analysis, the region can be designated as “high risk” and a ban placed on transfers from and to the region.

Dissemination of reports

The timely dissemination of a financial analysis of suspicious transactions and activities is crucial when attempting to prevent money laundering and terror financing. Success depends on the FIU’s ability to quickly analyze and disseminate data to the competent authorities on a national level, as well as to send information to foreign FIUs.

The data should be disseminated to national and international institutions. At the national level, the FIU disseminates STRs to law enforcement authorities for investigation and prosecution. The legal framework in the country prescribes to which institution the report will be submitted. In countries where the FIU is an administrative type, the financial analysis conducted by the FIU is an intelligence product and contains grounds for suspicion of money laundering and terror financing. In those cases, the FIU submits a report to the law enforcement agency with the authority to investigate. However, in cases where the FIU is a law enforcement-administrative type, the report is submitted to the public prosecutor’s office. Therefore, the jurisdiction and type of FIU (law enforcement or judicial) determines if it has the legal capacity to initiate investigations and file charges.

Considering the international character of money laundering and terror financing, there is a need for international cooperation among countries. The legal basis for this cooperation is found in bilateral or multilateral agreements or in memoranda of cooperation. International cooperation between FIUs can be based on a request or response or be generated from information shared spontaneously.

During a financial analysis, an FIU may need to submit a data request to another FIU. The exchange is done in accordance with standards established by the Egmont Group and through a secure website it developed. This direct line is also used for exchanging statistics, typologies, practical cases, training and workshops. In the EU, a decentralized and sophisticated computer network known as FIU.net has been established to support FIUs. Through a secure channel, FIUs, including Europol, can exchange data.

Freezing suspicious transactions

With the proper policies in place, money laundering and terror financing can be prevented in the early stages, i.e., when the proceeds of crime or the funds for financing terrorism enter the financial sector. At this stage, financial institutions should have the appropriate legal capacity to recognize suspicious transactions and suspend them. An FIU has no power to directly block funds. According to the Strasbourg and Palermo conventions and the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, countries should adopt legislative and other measures to enable the timely postponing and freezing of suspicious transactions, with an obligation to conduct an analysis and confirm the suspicion. FATF Recommendation 4 states that “countries should adopt appropriate legislative measures that will allow proceeds of crime to be confiscated.”

Recognizing suspicious transactions is a complex matter. Private sector financial institutions have a choice of carrying out or suspending any transaction. If they suspend a transaction, there is the possibility of losing a customer and the profit, but if they carry out the transaction, they risk being involved in money laundering or terror financing.

At this stage, cooperation between the FIU and financial institutions is extremely important. An FIU can produce indicators for recognizing suspicious transactions. A transaction can be suspended after a suspicious transaction report is submitted to the FIU. If the FIU determines that carrying out the transaction appears to be money laundering or terror financing, the FIU can submit a request to the bank to postpone the transaction. The time frame for postponing a transaction is different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, in North Macedonia the Financial Intelligence Office can submit a request to postpone a transaction for a maximum of 72 hours. During this period, the office asks the prosecutor to determine the provisional measures that should be taken. The request shall include data on the crime, the facts and circumstances that justify the need for the provisional measures, data on the people involved, the entity performing the transaction and the amount of money. If the public prosecutor determines that the request is reasonable, within 24 hours of receiving the request he/she submits a proposal to a judge. The judge is required to decide within 24 hours either to implement the provisional measures or to deny the prosecutor’s proposal.

Monitoring customers

The monitoring of a customer’s business relations (especially the ones that the bank has categorized as high risk) is essential to determining whether the customer is involved in money laundering or terror financing. FATF Recommendation 10 states that financial institutions should undertake due diligence measures when:

- Customers establish business relations.

- Customers carry out occasional transactions (above the designated threshold of 15,000 euros or when undertaking suspicious wire transfers).

- There is a suspicion of money laundering or terror financing.

- There are doubts about the veracity or adequacy of customer identification data.

An FIU should have the authority to request a legal order that will allow it to monitor business relations when there is a basis to suspect money laundering or terror financing. The order requires the relevant entities to monitor all transactions or activities of the people listed in the order. Unless otherwise specified in the order, the entity is required to inform the FIU before a transaction or activity is conducted. The monitoring of the business relation generally lasts three months, and for justified reasons this measure can be extended for one month but not more than six months.

Comments are closed.