Whether trafficked or smuggled, immigrants can be exploited

By Vladan Lukic, chief police inspector, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Serbia

Discussions about human smuggling in Southeast Europe or along the “Balkan route” are mostly related to illegal immigrants and refugee flows. From 2015 to the middle of 2016, huge numbers of refugees and immigrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere passed through Balkan countries into Western Europe — with Germany being the most common destination.

Organized crime saw an opportunity when the Balkan route closed in 2016 and began arranging cross-border human smuggling trips. In contrast to human trafficking, human smuggling is always international and always a cross-border activity. Under international law, human smuggling is banned under the same United Nations convention that bans human trafficking — the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime — but with the supplemental Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air. This protocol defines human smuggling as “the procurement, to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a state party of which the person is not a national or permanent resident.”

Serbia’s national criminal code defines illegal border crossings as “crossing the state border or attempting to cross the state border without permission,” and human smuggling as “intent to acquire a benefit to provide illegal crossing of the border of the Republic of Serbia.”

Trafficking vs. smuggling

The trafficking of humans and smuggling of immigrants are related and similar but also differ, and that can be confusing to those inexperienced in this area. While smuggling is always international, human trafficking does not need international elements; human trafficking can occur even within a small area. Undocumented migration across borders does not have to be coercive or exploitative, while coercion and exploitation are the main elements of human trafficking. The U.N. Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air emphasizes the mutual financial agreement between the smuggler and the migrant as a major component of the definition of smuggling. Another U.N. accord, the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, defines the act of trafficking people as the illegal transportation against the will of an individual, by use of coercion, bribery, force or deception.

Though they differ in definition and elements, these two types of organized crime can operate together. Smuggled migrants are highly vulnerable to exploitation because of the immigrant’s nondefined status. In a situation where migrants are exploited, an act of smuggling also becomes an act of trafficking. The exploitation can occur during transportation or at the destination. Even at the point of destination, even after separating from the smuggler, migrants remain vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. The demand for cheap labor and sexual services is present. Common migration push factors such as poverty and a lack of opportunity contribute to the vulnerability of immigrants.

Illegal immigration

In Serbia and other countries that faced the massive flow of migrants and refugees from 2014 through early 2016, a key challenge was to provide for their basic needs. Large numbers of immigrants passed through Serbian territory, most staying in the country for a very short time, from a few hours to a week. In 2014, Serbia registered 16,500 migrants who intended to request asylum. About 1,800 of them were female and especially vulnerable to trafficking. In 2015, the number of migrants seeking asylum was 35 times greater than the previous year, rising to about 580,000, with roughly 157,000 of them female.

The absence of an overview of migration flows led to a lack of understanding of the rights and protection mechanisms that should be provided to immigrants and refugees. Most immigration enforcement procedures were the result of political decisions, which led to immigrants feeling legally insecure and consequently mistrustful of the authorities. For that reason, migrants tried to avoid official border crossings and registration, which made it difficult to identify and protect possible victims of human trafficking.

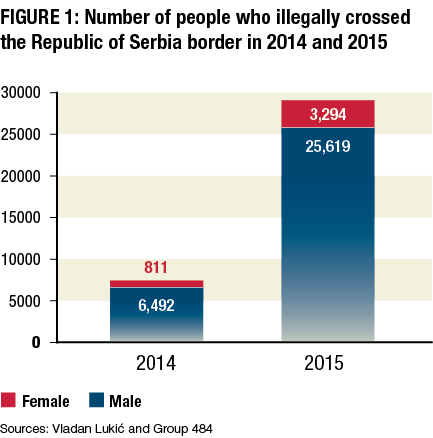

In 2014, 7,303 immigrants (6,492 male and 811 female) were caught crossing the border at unsanctioned crossing points and avoiding registration and contact with Serbian authorities. In 2015, the number of those caught was four times greater, increasing to 28,913 (25,619 male, 3,294 female) (Figure 1). At the beginning of 2016, after political will waned and opinions shifted about migrants and refugees, registered migrants stayed longer in Serbia amid diminished opportunities to safely cross the border. Additionally, government measures to better control state borders led to an increase in migrant smuggling.

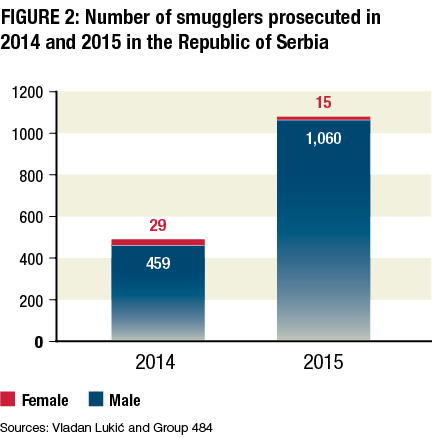

In 2014, Serbian police prosecuted 488 smugglers. The following year, more than twice the number of smugglers (1,075) were prosecuted (Figure 2). This was the result of improved government efforts to identify and prosecute smugglers and increased border controls, but also of increased smuggling activity. With improved measures to control illegal immigration and other activities at illegal border crossings, investigations of human smuggling increased. And as immigrants remained longer in Serbia and increasingly cooperated with state authorities, government agencies were better able to identify potential victims of human trafficking among the immigrant and refugee populations, and to provide better protection of and services to especially vulnerable groups such as women and children, thereby identifying indicators of human trafficking.

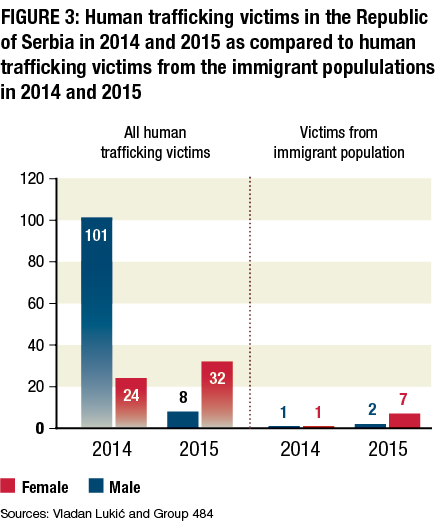

Investigations of human trafficking crimes decreased between 2014 and 2015, a change explained by the transfer of law enforcement resources from domestic human trafficking to border and cross-border activities. In 2014, Serbian authorities discovered 125 victims of human trafficking (101 male and 24 female). During the same period, only one male victim and one female victim were identified in the immigrant population. In 2015, 40 victims of human trafficking were identified (eight male and 32 female), with nine (two male and seven female) in the immigrant population (Figure 3).

Protection gaps

Female refugees lacked access to basic services in transit centers, including sexual and reproductive health care. “The lack of clear information and inability to access interpreters, especially female interpreters, hinder women and girls from accessing services and understanding their rights in the transit process, and a general lack of knowledge leaves them vulnerable to smugglers and other opportunists who prey on their desperation,” according to “No Safety for Refugee Women on the European Route: Report from the Balkans,” a report from the Women’s Refugee Commission. “Not only are government officials inadequately equipped to identify and ensure appropriate services are available for vulnerable populations, but efforts to incorporate much-needed services are negated. Civil society organizations with relevant gender expertise are typically excluded from the places where they could be most helpful,” the report concluded.

Serbia is a transit country on the Balkan route, and it is difficult to know whether females were subject to violence, fraud and exploitation, and if they were, to what extent. Due to the relatively short stay of migrants, a relationship of trust could not be established, so victims were unable to openly communicate their experiences or ask for help. Victim identification is also difficult for other reasons. Refugees are not motivated to identify themselves as victims and report abuses to authorities because their aim is to reach the European Union, not to stay longer in Serbia or to separate from their group.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Serbia that work to identify human trafficking and smuggling victims and provide services to migrants often comment that Serbian government officials — even law enforcement (Ministry of Internal Affairs) — that are first to come into contact with immigrants and refugees are not sensitive enough, do not have the knowledge and training to identify human trafficking victims, and lack the capacity to accommodate, service and protect these victims. Also, medical care field teams did not record any injuries that could be attributed to violence; however, the NGOs recorded that refugees arriving from other Balkan countries had visible injuries, bruises, scratches and scars, a consequence of violence and torture by officials.

According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees’ Guidelines on International Protection and the EU Directive on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims, help should be provided to victims when trafficking indicators exist. To prevent secondary victimization and unnecessary suffering, investigators should prohibit unnecessary contact between victims and the accused.

Providing services and support to victims should not be conditioned on cooperation during the investigation or court process. The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women expressed concern that “victims of trafficking who do not cooperate with the police in the investigation and prosecution of traffickers are excluded from the protection.”

The lack of precise indicators to identify trafficking and smuggling victims and the insufficient training of government officials who are first to contact refugees and immigrants hinder the early detection of human trafficking victims. Failing to implement the minimum standards for protecting migrants and human trafficking victims has consequences for the refugee and immigrant populations.

Recommendations

Human trafficking and smuggling are related, but they are not the same. As a vulnerable population, migrants can easily become victims of human trafficking. Because migrant and refugee flows through Southeast Europe spiked in recent years, governments should make efforts to suppress smugglers, to adequately work with refugees and immigrants to identify possible victims of human trafficking, and to provide necessary services and protection to victims in accordance with international conventions and standards. In that context, governments should:

- Develop and implement standards and procedures at all stages of victim protection, from identification to reintegration, and develop protocols about cooperation between government and NGOs.

- Allocate staff and resources to adequately respond to human trafficking and human smuggling crimes.

- Educate government employees about human trafficking, especially those who first come into contact with migrants and refugees, and increase their sensitivity to better recognize potential human trafficking victims.

- Make efforts to increase the capacity to accommodate refugees and immigrants, especially the capacity of shelters for possible human trafficking victims, and to ensure service and support to better overcome victim traumatization.

Comments are closed.