CCP’s overseas policing draws international condemnation

By Indo-Pacific Defense Forum

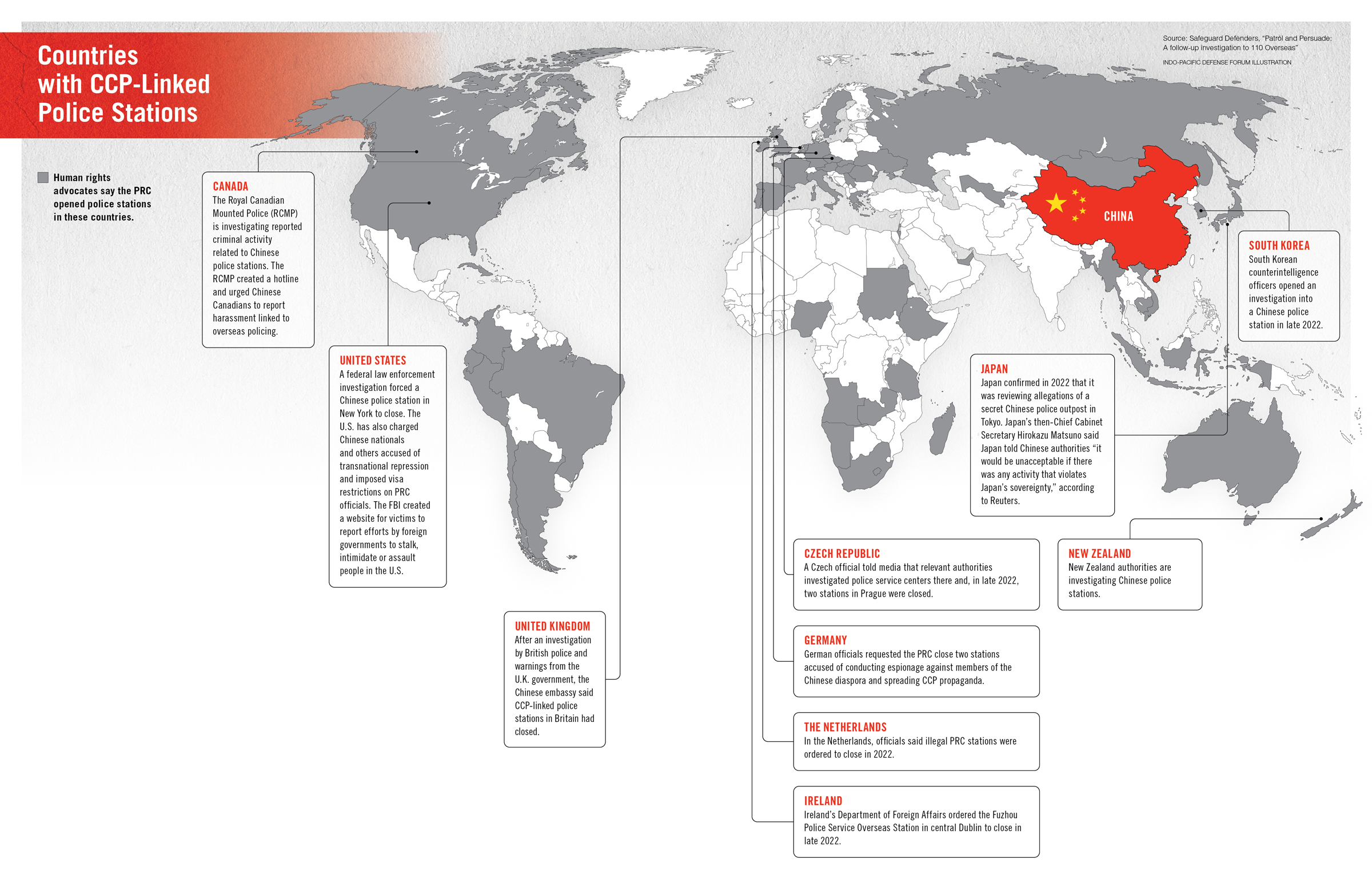

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) continues to face international criticism for violating the sovereignty of nations across the globe with its “overseas police service stations,” clandestine offices established in many cases without the approval or knowledge of the countries that become their unsuspecting hosts. Rights advocates say the stations are bases that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) uses to track and harass dissidents living abroad. Those findings have sparked investigations and criminal charges from Europe to the Indo-Pacific to North America.

Safeguard Defenders, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) based in Spain, revealed 102 of the police outposts in 53 countries. The human rights group’s research highlights open-source Chinese reports touting the stations’ existence on every continent except Antarctica, and the NGO says similar international facilities, often referred to as “service centers” in Chinese reporting, are also linked to police in the PRC. While the PRC appears to have policing arrangements with a handful of the countries, media reports from more than a dozen nations indicate the offices opened covertly and that law enforcement and government officials in unwitting host locations consider them illegal.

The CCP insists the offices provide Chinese citizens overseas with administrative services, such as driver’s license renewal, that were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Reports from CCP authorities and state and party media, however, suggest they predate the pandemic. “Public security bureaus” in the PRC began work on the outposts as early as 2016, according to Safeguard Defenders.

Furthermore, CCP officials have said publicly that 230,000 Chinese nationals were “persuaded to return” to face criminal fraud charges in the PRC from April 2021 to July 2022. To understand those campaigns, the human rights group analyzed CCP tactics, which is how researchers first found evidence of the secret police stations, Laura Harth, a campaign director for Safeguard Defenders, told a Canadian House of Commons committee in March 2023. The group says most of the “returns” lauded by the PRC are “non-traditional, often illegal means of forcing someone to return to China against their will, most often to face certain imprisonment.” Experts say Chinese courts have a conviction rate of more than 99%.

The CCP’s overseas policing is problematic partly because it does not adhere to widely held standards such as judicial fairness. The CCP’s brand of persuasion includes threatening, intimidating, and harassing overseas targets and imprisoning their relatives in the PRC, according to the Safeguard Defenders’ report, “110 Overseas: Chinese Transnational Policing Gone Wild.”

The same methods, the NGO says, are integral parts of the CCP’s widely documented Fox Hunt and Skynet operations, global programs to apprehend purported Chinese fugitives — and known for violating the laws of sovereign countries and abusing human rights. The targets are public officials and businesspeople accused of corruption. “But some of these people didn’t do what they are charged with having done,” John Demers, the former head of the United States Justice Department’s national security division told the ProPublica news organization in 2021. “And we also know that the Chinese government has used the anti-corruption campaign more broadly within the country with a political purpose.” Fox Hunt has overlapped with the CCP’s illicit overseas police stations, researchers wrote.

‘Educate’ and ‘persuade’

Safeguard Defenders uncovered reports of numerous “persuasion to return” operations connected to Chinese police stations:

- One suspect returned to the PRC after being “educated” by the staff at a station in Madrid, Spain, who were working directly with police in Qingtian in China’s Zhejiang province, according to Chinese media reports.

- Officials at a station in Belgrade, Serbia, run by Qingtian police, contacted a Chinese national accused of theft and used the WeChat social media platform for “persuasion,” the Zhejiang Internet Radio and Television Station reported in 2019.

- The head of a police station in Paris founded by Zhejiang authorities told Chinese media in 2021 that he was “entrusted by the domestic public security organs to help persuade a criminal who had been absconding in France for many years to return to China through many visits.”

- Police in China’s Jiangsu province said in July 2022 that their “police and overseas linkage stations” assisted in the capture or persuasion of 80 “criminal suspects” returned to the PRC, although the report does not specify where those operations took place.

Not all of the CCP’s transnational harassment is linked to its illicit police outposts. Law enforcement agents and human rights advocates have documented other examples of coercion on foreign soil. Safeguard Defenders’ 2022 “Involuntary Returns” report detailed instances in Australia, Canada, Southeast Asia, the U.S. and elsewhere. The group told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. that it found seven cases of people living in Canada who were targeted by CCP agents. They included a former Chinese judge accused of corruption after criticizing the PRC’s criminal system. The NGO’s report said police in the PRC tried to force his return by arresting his sister and son.

Since 2020, the U.S. Justice Department has criminally charged at least 51 Chinese citizens and a dozen PRC-linked suspects after investigators found evidence of forced repatriation schemes, surveillance, harassment and attempts to coerce Chinese residents in the U.S. The accused include 40 officers with the PRC’s National Police, at least one other police officer and a court official in the PRC. Among the victims are a naturalized U.S. citizen who helped lead the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing, an artist and Chinese national who criticized the CCP, and a Chinese-born U.S. resident accused of financial crimes in the PRC.

Elsewhere, the CCP has kidnapped targets. Laws relating to the PRC’s supposed anti-corruption operations explicitly allow for “unconventional measures,” such as abduction and entrapment. “They may use luring or entrapment of individuals,” Harth told news broadcaster CNN. “So, they might try to get a person to a country where it’s easier to … bring them back to China because the judicial safeguards are less in that particular place. But they may even use kidnapping. … Chinese authorities expressly say that kidnapping is a legitimate means to retrieve a person.”

Expanding reach

The CCP admits that it wants more power over global security norms and believes its Ministry of Public Security has a part to play in gaining influence, the Center for American Progress, a U.S.-based policy institute, said in a 2022 report on “The Expanding International Reach of China’s Police.” It cited a CCP conference at which police and legal officials were encouraged to “grasp the new characteristics of the internationalization of public security work” and a former police official who called for a “new system of public security international cooperation work” to achieve the CCP’s overseas goals.

Beijing has formal policing agreements with various nations and participates in police operations outside the PRC. Its clandestine operations, however, seem aimed at sidestepping democratic laws and norms as it seeks to export the PRC’s “social management” regime. The strategy conflicts with the PRC’s refrain about its own sovereignty. “The PRC is very big on claiming territorial sovereignty,” Harth told CNN, “claiming sovereignty when it comes to, you know, criticizing people that call out their human rights record.”

Rebuffing the CCP

Meanwhile, the PRC has been spurned by nations where it openly proposed expanding its law enforcement role, with one Pacific island country canceling a policing pact. Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka said in January 2023 that police would cease working with PRC security personnel. The Fiji Police Force and the CCP’s Ministry of Public Security agreed in 2011 that Fijian officers would train in China, which would send its police officers to Fiji for three- to six-month programs. The CCP also appointed a police liaison officer to be based in Fiji. “There’s no need for us to continue,” Rabuka told The Fiji Times newspaper. “Our system of democracy and justice systems are different, so we will go back to those that have similar systems with us.” Officers from countries including Australia and New Zealand will stay in Fiji, he said. The U.S. has also committed to expanding training and capacity-building programs in the Pacific island country, the Fiji Police Force said in February 2023.

Soon after signing a controversial and secretive security agreement with the Solomon Islands in 2022, Beijing failed to persuade a larger contingent of Pacific island countries to sign a regional deal that would have covered policing, security and other cooperation. Two of the Pacific island countries that rejected Beijing’s proposal have since agreed to security arrangements with Australia. Vanuatu will cooperate with Canberra in policing, disaster relief, defense and cybersecurity, the nations announced in December 2022. An Australia-Papua New Guinea (PNG) pact will help build PNG’s capacity in areas such as policing, health security and biosecurity, according to officials.

International outcry

Safeguard Defenders’ Harth told the Canadian House of Commons in March 2023 that the CCP’s transnational repression should be publicly denounced by nations where it is discovered. Her organization calls for governments to investigate CCP-linked overseas police activities, set up reporting and protection mechanisms for at-risk communities, and coordinate information sharing among like-minded countries. Safeguard Defenders has also called on governments to “urgently review — and possibly suspend” police cooperation agreements with the PRC.

Authorities worldwide have taken action:

- The Royal Canadian Mounted Police confirmed in March 2023 that it is investigating five Chinese-run police stations across the country, according to Le Journal de Montreal newspaper, and that Chinese nationals living in Canada had been victims of activities possibly linked to the centers.

- Japan’s then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Hirokazu Matsuno said in December 2022 that the nation “will take all necessary steps to clarify the situation” after allegations surfaced of a Chinese police outpost in Tokyo. Matsuno said Japan informed Chinese authorities that any activity violating its sovereignty would be “unacceptable,” according to Reuters.

- New Zealand authorities opened an investigation into allegations of an illicit Chinese police station. A Green Party spokeswoman told the New Zealand Herald newspaper in December 2022 that Chinese-born Kiwis have warned that Beijing is conducting surveillance at clandestine police outposts. Police and military personnel in South Korea, as well as foreign ministry officials, are investigating an alleged covert Chinese police station in Seoul, the Yonhap News Agency reported.

- In the U.S., Federal Bureau of Investigation agents seized material from a suspected Chinese police station in New York City and in April 2023 charged two men with conspiring to act as agents of Beijing in connection with opening and operating the illegal station. The office closed in late 2022 after its operators learned of the investigation, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

Additionally, authorities in Austria, Chile, the Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom are investigating suspected Chinese police stations in their nations. Harth says those measures are a positive first step. “The first thing is really call out the Chinese authorities on what they’re doing. … Make it very clear that we think this is clandestine, this is illegal, this is a brazen violation of national sovereignty and international law,” she told CNN. “The second is, building on that coalition, really share best practices, share information, share intelligence. So, we need democratic countries to actually work together, law enforcement to work together and come together on this.”

This article was previously published in Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, a publication of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

Comments are closed.