Europe reconsiders Chinese engagement in the wake of Russia’s war on Ukraine

By Dr. Valbona Zeneli, senior fellow, Atlantic Council

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has shaken the foundations of the European security architecture, challenging its reliance on defense guarantees from the United States, cheap energy from Russia and cheap products from China. German chancellor Olaf Scholz described the European awakening as a Zeitenwende — historic turning point — for European foreign and security policies, consisting of efforts to bolster collective defense and military spending, and recognizing the challenge of energy dependence on Russia. China’s role as a strategic partner of Russia and its failure to openly condemn the attack on Ukraine has led to further distrust of Beijing.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Chinese enjoyed nearly unfettered access to Europe’s economic, research and academic domains. Chinese Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping’s friendship pact with Russian President Vladimir Putin resulted in negative reverberations throughout European capitals and raised concerns about China’s strategic ambitions and their impact on Europe. The war in Ukraine has compelled an evolution in Europe’s assessment of Chinese ambitions, which is likely to impact future engagement between China and Europe.

Before February 2022, European countries had differing security perspectives, resulting in regionalized threat assessments. Many Eastern European countries were concerned with the threats posed by Russia, while others were concerned with issues such as migration. Russia’s full-scale aggression sparked a remarkable unification of the West in implementing harsh sanctions against Russia and supporting Ukraine. The European Union has been united in sanctioning Russia, publishing its 13th package of sanctions in February 2024, which focused on further limiting Moscow’s access to military technologies and listed additional companies and individuals involved in the war effort, and a 14th in June, which is “designed to target high-value sectors of the Russian economy, like energy, finance and trade” and make evading sanctions more difficult. At the same time, the EU provided military assistance to a non-EU country for the first time, opened its doors to Ukrainian refugees and granted the opening of EU accession negotiations to Ukraine and Moldova. Finland and Sweden joined NATO.

Conflict boosts defense spending

The citizens of NATO countries — almost 75% — see the Alliance as the essential organization for the defense and security of the trans-Atlantic community, according to a 2023 NATO poll. The U.S. has been the single largest contributor to the Alliance, but the return of war to Europe brought a realization of the need to increase defense spending. The most disproportionate balance of burden sharing in NATO history was registered in 1952, when the U.S. funded 77% of the Alliance’s total spending. The closest to parity was registered in 1999, during the Balkans conflicts, when the U.S. paid only 55%. Although most European governments ignored the 2014 Wales Summit commitment to spend 2% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, they became real about efforts to bolster collective defense in 2022, driven by Germany’s pledge to reach the 2% target and allocate an additional 100 billion euros to a special defense fund. As a result, in 2023, defense spending across European NATO members and Canada resulted in a total increase of 11%, adding more than $600 billion for defense. Expectations are that 18 NATO Allies will spend 2% of their GDP on defense in 2024, compared with 2014 when only three met the target.

From a strategic perspective, European countries found a new appreciation of the U.S. as the main provider for the Alliance’s security, as well as a realization that “strategic autonomy” was just a dream because of the lack of European military capabilities and need for the U.S. nuclear umbrella to deter Russia’s nuclear blackmailing.

European energy diversification

The war in Ukraine challenged the model of Europe’s dependence on cheap energy from Russia. In 2021, Russia was the largest supplier of its petroleum products and provided 45% of Europe’s gas needs. After the war broke out, the European Commission implemented a successful energy diversification, with the objective of making the EU independent from Russian fossil fuels before 2030 while expanding European renewable energy sources. This led to serious consequences for Russia as it lost an important natural gas and oil market. While the EU made unprecedented strides to pivot from Russian energy, the Kremlin’s decision to impose additional payments on European customers through its “gas-for-ruble decree” and the temporary suspension of gas transportation via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline pushed Europe toward quicker independence.

Energy diversification in real time will cost the EU at least $220 billion per year, but in the long run it is in line with what the EU is spending to achieve its Green Deal objective, which envisions $80 billion in annual funding to members for the clean energy transition from 2025 to 2032, according to the EU.

Strong political messages from the EU

Before the war, there were concerns in the trans-Atlantic community about vulnerabilities that would be created by the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. To keep Russia as a partner, these concerns were dismissed using economic justifications and the trade interdependence argument. The current security situation in Europe will certainly recalibrate Western assumptions about global economic interdependence, international law and institutionalism, and as a result, its future relations with Russia and China.

China’s refusal to condemn Russia’s war in Ukraine and its enabling economic stance toward Russia have galvanized concerns in Europe. Beijing and Moscow have strengthened their diplomatic and economic relations in the past two years. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen took a strong stance during the summit in Beijing in December 2023, stating that the defining issue for the EU in its bilateral relationship with China would be the Chinese response to the “Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.” European leaders have pressed their Chinese counterparts to help prevent Moscow’s attempts to circumvent sanctions, even threatening that the EU could impose sanctions on Chinese entities thought to be sending dual-use items to Russia.

Beijing, failing to condemn the Russian invasion, released on February 24, 2023, a 12-point position paper on “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis.” The missing condemnation was anticipated from the title of the paper and did not offer anything new in terms of Beijing’s supposed neutrality, confirming its alliance with Russia in the ideological confrontation with the West. The paper offered some insights about China’s positioning on global power dynamics, and with anti-U.S. rhetoric, in its supposed rejection of double standards. During a meeting with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference in February 2024, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated that China “does not take any advantage of the situation and does not sell lethal weapons to conflict areas or parties to the conflict” in an attempt to present Beijing as a neutral actor.

China has consistently abstained from United Nations resolutions focused on condemning Russia. But after intense pressure from the West, and after von der Leyen visited China in April 2023 and called on Beijing to “use its influence in a friendship that is built on decades with Russia,” Xi slightly changed his stance. He held a call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy that marked the most concrete step by Beijing to take the role of mediator. Following up, China (together with India) voted in favor of a U.N. resolution that explicitly acknowledges the “aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine,” although it was a broader resolution that called for closer cooperation between the U.N. and the Council of Europe. Beijing’s slight change of language toward Russia was really a diplomatic change and, although symbolic, it underscored adjustments in Beijing’s course aimed at maintaining favorable relations with EU institutions and leaders as a counterbalance to the U.S.

Realpolitik drives China and Russia together

There is better understanding in the international community that realpolitik considerations drive China and Russia together. They are natural allies in their predilection to stand in opposition to the Western alliance led by the U.S. Both are subject to U.S. sanctions because of their assertive regional activities that violate international norms: Russia in Eastern Europe and China in the Western Pacific. Together, China and Russia complement each other — Russia with its nuclear weapons and hydrocarbon riches, and China as the economic superpower. Michael O’Hanlon and Adam Twardowski explain in their 2019 paper for the Brookings Institution, “Unpacking the China-Russia ‘Alliance’,” that there are four ways to look at this relationship, from transactional cooperation, economics and arms sales to military collaboration and training. China and Russia are strategic partners, and this status was elevated on February 4, 2022, on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when Putin and Xi met in Beijing and signed the “Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development,” declaring that “friendship between the two states has no limits.”

Economic and trade relations between China and Russia have been dominated by oil and gas, and they have intensified after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent EU sanctions. In a videoconference with Xi in December 2022, Putin proudly announced that “Russia has become one of the leaders in oil exports to China,” adding that Russia was China’s second-largest supplier of pipeline gas and fourth-largest of liquefied natural gas. According to Russian statistics, energy exports to China increased by 64% in 2022 compared with 2021.

In 2023, China became the largest buyer of Russian oil and gas, purchasing 47% of Russia’s crude oil exports, followed by India (32%), the EU (7%) and Turkey (3%). In total, half of Russia’s oil and petroleum exports in 2023 were shipped to China. Similarly for coal, China was the largest buyer, purchasing 45% of Russia’s exports in 2023.

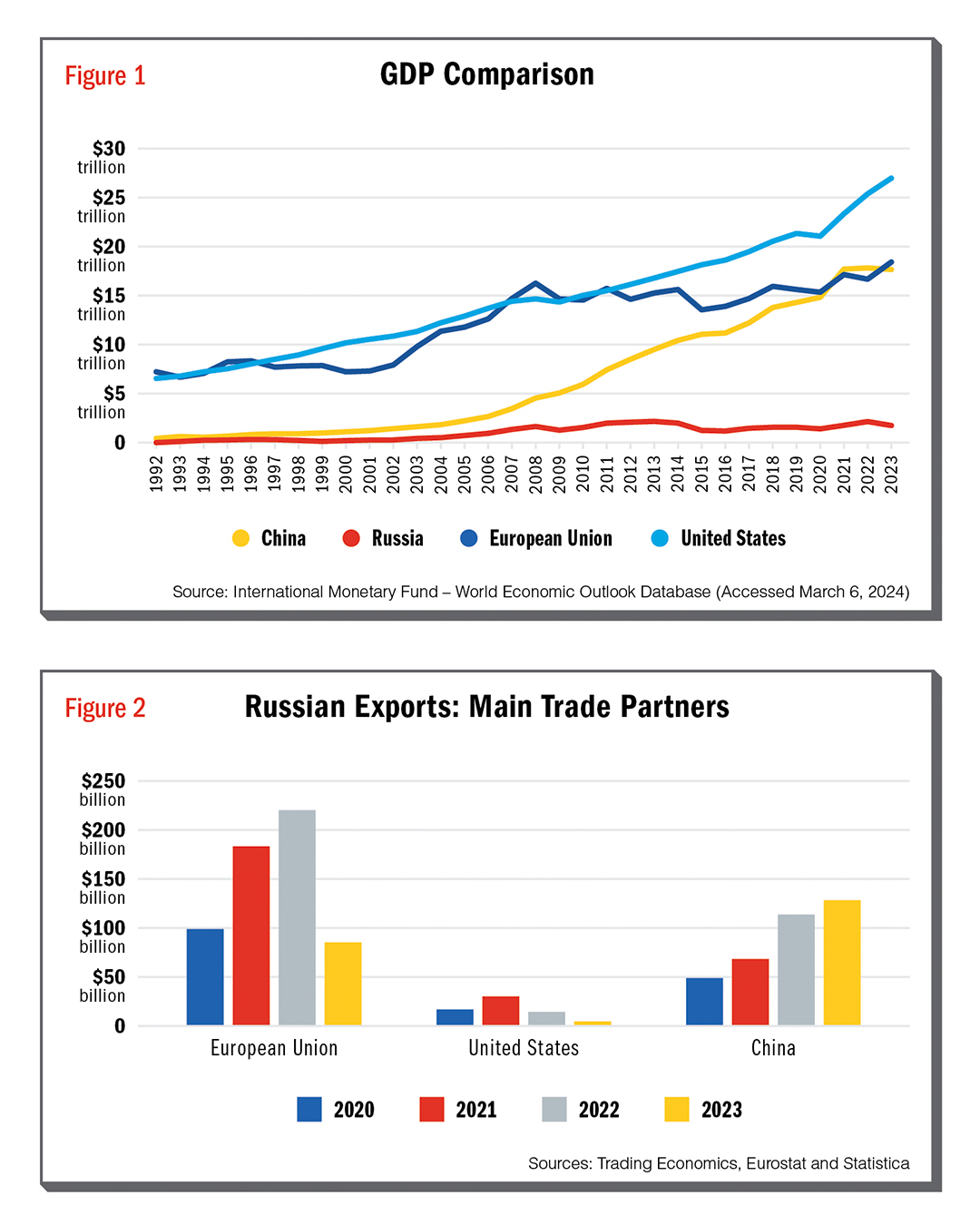

However, it is important to look at the bigger picture. For China, Russia is not among its main trading partners, compared with the EU, Japan, South Korea and the U.S. When it comes to the economic weight of the two countries, the difference is vast, with Russia’s economy ($1.9 trillion) being only 10% of China’s ($17.7 trillion) in terms of GDP, 10% of the EU’s ($18.3 trillion), and only 7% of the U.S. economy ($27 trillion), according to International Monetary Fund data.

Chinese exports to the Russian market make up only 2.2% of its total exports (ranking as the 15th-largest market) and 4.6% of its imports, being the sixth-largest market in 2022, according to Trading Economics statistics. In 2022, 75% of total Russian exports to China ($85 billion out of $114 billion) were mineral fuels, oils and distillation products.

In 2023, trade between China and Russia grew by 26% compared with the year before, hitting a record high of $240 billion. Chinese exports to Russia grew by 47% in one year and imports from Russia grew by 13%. Trade between China and Russia has increased 2.7 times since 2014, from $87 billion to $240 billion. In fact, the Kremlin launched its pivot to China in 2014, following its annexation of Crimea, first to diversify from Europe and, after 2022, because of unprecedented Western sanctions.

Two years into the war in Ukraine, Russia is increasingly dependent on China as a market for its commodities and as a source of imports for critical goods and supplies that fuel its war machine. Beijing is also Putin’s most important diplomatic partner, giving him publicity through state visits and summits. On the other side, China is increasing its geoeconomic leverage over Russia by securing lower prices on its hydrocarbon needs and conquering the Russian consumer market. Another advantage for China is that more than 95% of trade between the two countries in 2023 was done in yuan and rubles to de-dollarize their trade, since Western sanctions limit Russia’s access to the dollar and euro.

While Western sanctions were meant to send a strong political message to Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, Moscow is undermining the sanctions by diverting its trade to Asia, excluding Australia, Japan and South Korea, which have joined the sanctions.

Indo-Pacific security

The war in Ukraine has brought some degree of realization that armed conflict over Taiwan is not unimaginable and has opened new discussions surrounding the risk of escalation in the Taiwan Strait and the potential economic and security consequences for Europe. One of the main takeaways from the Russian aggression against Ukraine is the autocratic leaders’ disregard for international law, and the inaccurate assumption of the Western community that economic interdependence was a sufficient rationale for good diplomatic relations.

Several European leaders have been clear on this issue. Germany’s minister of foreign affairs, Annalena Baerbock, has stated that a “military escalation in the Taiwan Strait, through which 50% of world trade flows every day, would be a horror scenario for the entire world.” Baerbock warned that a “unilateral and violent change in the status quo would not be acceptable.” Similarly, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, in criticizing the Chinese military exercises in the Taiwan Strait, stated that the “EU is an important market for China which risks to be closed if Beijing decides to attack Taiwan.” Von der Leyen has also warned China “not to use force against Taiwan” and that the union is “standing strongly against any unilateral change of the status quo, in particular by the use of force.” These comments also highlight the difference with French President Emmanuel Macron and his remarks during his visit in April 2023 to Beijing implying that “Taiwan is not Europe’s problem.”

De-risking from China

China has been among the EU’s largest trade partners, with a 2022 trade volume of 856 billion euros ($926 billion), the largest partner for its imports, and the second-largest partner for EU exports. Export volume is heavily tilted in favor of China by about 396 billion euros ($429 billion), with a total value of imports of goods from China to the EU of 626 billion euros ($678 billion) and 230 billion euros ($249 billion) of EU exports into the Chinese market, according to EU statistics.

The value of Chinese exports to the EU increased almost nine-fold from 2002 to 2022. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU increased in the past two decades, especially after the Eurozone crisis, with an increase of almost 50 times in eight years, from less than $840 million in 2008 to a record 48 billion euros ($52 billion) in 2016, according to data from the Mercator Institute for China Studies. The increase in Chinese FDI in the global economy happened after Beijing loosened restrictions on outward FDI in 2014, and large merger and acquisition transactions drove Chinese FDI in the European market.

Chinese FDI in the EU reached a peak in 2016, followed by a multiyear decline to 7.9 billion euros ($8.5 billion) in 2022, a drop that takes Chinese FDI back to 2013 levels. The main reason is the decline of Chinese merger and acquisition activities in the EU, resulting from tightened investment-screening procedures of Chinese FDI that have affected the acquisition of strategic assets in Europe by Chinese state-owned enterprises and critical infrastructure investment. However, this is in line with the decrease of Chinese outbound investment in general ($117 billion), which dropped by 23% in 2022 compared with 2021 because of the global crises triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Resulting uncertainty and shifts in global financial conditions have increased caution and suppressed global FDI. A tightening of capital controls and crackdown on highly leveraged private investors by Beijing led to a sharp drop in China’s global outward FDI.

Chinese investment in Europe is primarily concentrated in four countries: the United Kingdom, followed by France, Germany and Hungary. The total stock of Chinese FDI in Europe (EU plus the U.K.) has reached $245 billion since 2000. The stable legal, regulatory and political environment in Europe offers unique business opportunities for Chinese investors, who value its open markets, intellectual property rights and strategic location. It remains to be seen whether the EU will follow the lead of the U.S. in the establishment of an outbound investment-screening mechanism, as it did for the inward FDI-screening mechanism. In 2022, we witnessed a sudden increase of European FDI in Chinese markets, despite slowing overall FDI in China, as EU investment grew by 92%.

In March 2019, the European Commission published its Joint Communication “EU-China — A Strategic Outlook” in which China was shifted from “strategic partner” to “negotiating partner” and the EU sought to find a balance of interests with Beijing as an “economic competitor” in the pursuit of technological leadership and as a “systemic rival” promoting alternative models of governance. This was followed by the EU’s first investment-screening framework, established to make economies better equipped to identify and mitigate the risks of foreign investment to security and public order. This was a direct response to China’s increased influence in the European market using unfair practices and state subsidies. Beijing’s interests in Europe are economic and geopolitical, focused on strategic investment in the core EU countries and infrastructure development projects on their periphery. These interests are related to the needs of Chinese companies — new technologies, know-how, broader access to the European market — and their goal of becoming key players in integrated regional and global value chains.

China and the EU approved the new Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) in December 2020 after seven years of negotiations and 35 rounds of talks; it is considered the most ambitious agreement that Beijing has ever concluded with a trading partner. The CAI appeared as a pragmatic step forward in regulating trade and investment with China in terms of liberalization of investment, rules against the forced transfer of technology, a more even economic playing field and commitments to sustainable development. But the CAI was also controversial: China skeptics, as well as human rights advocates, had urged Brussels to prioritize those issues with Beijing. Meanwhile, the Chinese economy has become more state-driven, and Chinese leaders have more explicitly disavowed Western liberal values.

Rightly, the EU parliament suspended the CAI’s ratification in April 2021 and passed a motion to freeze trade after Beijing sanctioned some EU Members of Parliament for their criticism of China’s treatment of its Uyghur population in Xinjiang province. Later, in March 2023, von der Leyen put the future of the shelved CAI firmly in doubt.

In June 2023, the European Commission issued its first ever European Economic Security Strategy, outlining a pragmatic view of the EU’s required responses to current economic and geopolitical challenges. This ambitious new course was further emphasized a few months later during von der Leyen’s State of the Union speech, where she focused on the need for ensuring resilience across supply chains to achieve a greater diversity of sources to meet critical needs and promote technological supremacy, while seeking to maintain open markets. The EU’s China de-risking strategy regarding supply chains — especially focusing on cleantech, the solar industry and electric vehicles — aligns with the economic doctrine of U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration, as the EU proposes to establish export controls on specific technologies based on the U.S. model.

In response, China’s minister of foreign affairs, Wang Yi, stated during the Munich Security Conference in February 2023 that trying to cut his country out of trade in the name of avoiding dependency would be a historic mistake. Beijing also criticized Germany’s efforts to avoid overreliance on trade with China and to diversify its supply chains, calling them “protectionism.”

From 16+1 to 13+1

Twelve years after the announcement of the 16+1 Initiative, a precursor of the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) expansion into Europe, Beijing’s economic engagement with the 16 countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) lags far behind the initial enthusiasm. In 2012, the 16+1 Initiative (17+1 when Greece joined in 2019) was established between China and 16 CEE countries with the aim to further economic cooperation.

In May 2021, Lithuania pulled out of the China-led bloc (again, then, 16+1) and urged other EU countries to quit as well. The decision was based on Lithuania’s foreign policy that emphasizes the importance of NATO and anti-authoritarianism, and happened after Lithuania and Taiwan opened diplomatic offices in their respective capitals. This event angered China and led to an economic coercion campaign against Vilnius, negatively affecting Lithuanian exports to China. Lithuanian products were removed from the Chinese customs system as a country of origin, thus banning not only Lithuanian goods but also European products with Lithuanian components.

The EU strongly supported Lithuania, even lodging a complaint against China at the World Trade Organization. In a response to Beijing’s economic attack, the EU published a regulation in September 2023 to protect members from economic coercion, introducing a new tool to protect trade and fight unfair trade practices.

Following Lithuania’s example, Latvia and Estonia quit China’s economic cooperation platform in August 2022, declaring that they will continue to pursue “constructive and pragmatic relations” with Beijing within the framework of the EU and in accordance with the rules-based international order and values such as human rights. The announcement came just after China intensified its military activities around Taiwan after the visit of the then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

The decisions of the Baltic countries to leave the bloc are not related only to failed economic results and promises but also to the diplomatic and economic costs of dealing with China in an era of strategic competition and tense relations between Beijing and Washington, as all three Baltic countries see the U.S. as the main security guarantor in the region.

This angered Beijing to the point that China’s ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, denied the Baltic states’ sovereignty, stating that former Soviet republics do not have “effective status in international law.” This caused diplomatic outcry across the Baltics and the EU. EU foreign affairs chief Josep Borrell called the comments unacceptable and said the union “can only suppose these declarations do not represent China’s official policy.” Indeed, Beijing denied the declarations were official policy and affirmed that it “respects the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries and upholds the purposes and principles of the U.N. Charter.” Still, the ambassador’s comments illustrated China’s aggressive “wolf warrior diplomacy.”

Most importantly, Italy, whose membership in OBOR had been viewed as one of China’s most symbolic wins in Europe, decided to leave the initiative right before the EU-China Summit in Beijing in December 2023. Italy’s decision to leave OBOR, making it 13+1, is not just a reflection of frustration over failed projects and unmet promises but is based on a real commitment to defending democratic values and human rights.

Beijing aims to bilateralize relations

A major concern arising from increased Chinese influence in Europe is Beijing’s attempts to bilateralize relations with EU members, which has the potential to affect the internal cohesion of the union. Chinese investments in strategic sectors of European countries have created economic interdependence for political ends, interfering in EU decision-making processes regarding China matters. This is mainly related to issues of human rights, such as the blocking of an EU statement after the International Arbitration Court ruling on the South China Sea, and criticism of OBOR.

The EU lacks effective mechanisms to manage serious conflicts inside its institutions. China is leveraging the EU unanimity rule to block statements or actions that Beijing considers disadvantageous. Similarly, when it comes to the Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) used in almost 80% of EU legislation, a group of 13 member states is enough to defeat any measure. With 13 EU member states now members of OBOR, it would be possible for Beijing to influence the union’s decision-making. To mitigate this issue, a Franco-German expert group published the report “Sailing on High Seas — Reforming and Enlarging the EU for the 21st Century” where it is proposed to expand the QMV in foreign policy, which can be done without amending EU treaties.

Beijing has encouraged the concept of European strategic autonomy in attempts to divide the trans-Atlantic community and amplify tensions within Europe. Beijing also aims to create division in the trans-Atlantic Alliance, hoping that the EU can act as a counterbalance to perceived U.S. hostility toward China. To achieve this, Beijing tweaks its diplomatic relationship with the EU and its member states using trade and market openness as its main levers.

Strategic gamesmanship

Whether by strategic design or happenchance, China and Russia have become increasingly aligned across the economic and geopolitical spectrum since 2014. All indicators on the horizon suggest this trend will continue with consequences that are difficult to plot with any reasonable certainty. This requires reflection from the perspective of the EU and the U.S., especially concerning a coordinated response. It is obvious that the EU and the U.S. must work more closely together in developing a coordinated trans-Atlantic strategy that addresses China and Russia as an anti-Western bloc. Europe also needs to think through current policy shortfalls that allow individual countries a wide degree of geopolitical and economic maneuver room, which creates conditions that ultimately favor China. The extent and value of Europe’s economic dependencies and public attitudes toward China should be subjected to continual national security scrutiny to ensure Europe’s vital interests are not eroded one deal at a time.

Comments are closed.