By Lt. Col. Ryan B. Ley, U.S. Air Force, Marshall Center senior fellow

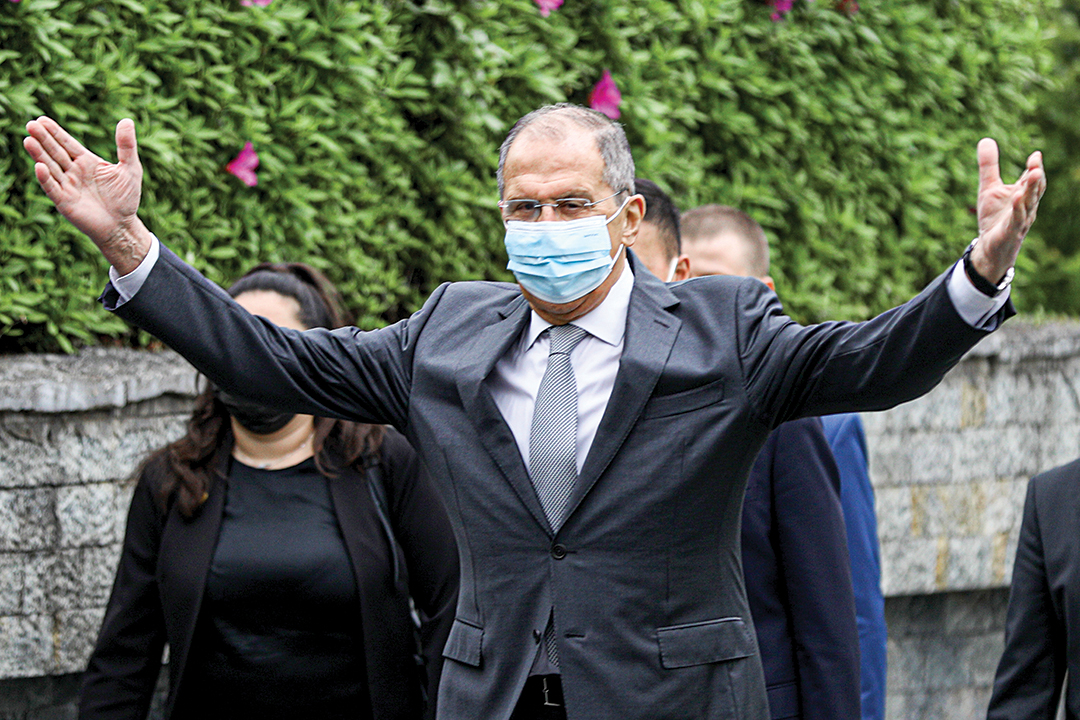

Photos By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Over the past 500 years, 75% of the cases (12 out of 16) in which a rising power has confronted a ruling power have resulted in bloodshed, according to Graham Allison in his 2018 bestseller, “Destined for War.” In today’s context, China is the rising power and the United States is the ruling power. But what about a declining power like Russia, which still has great power ambitions and nuclear weapons on par with the U.S.? What if it aligns itself with the rising power? On the surface, it seems that such a scenario — which is precisely what is occurring right now — could lead to global catastrophe. However, in the modern era, maybe there is hope of avoiding the dreaded Thucydides Trap. In fact, Allison’s team at the Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs concluded that the last two great power confrontations (including the Cold War) ended peacefully. Nevertheless, if the Thucydides Trap is to be avoided, a coherent U.S. strategy — currently at a crossroads between two vastly different presidential administrations — is paramount.

To counter Sino-Russian alignment, and thus reduce the potential for war, a refocused U.S. grand strategy that is optimized for a multipolar world must return to an offshore balancing strategy that provides a more sustainable and collective approach through the optimization of defense posturing and the leveraging of regional allies.

Strategic partnership, alliance or entente?

Ultimately, the mere characterization of the Sino-Russian relationship is not in itself important. But a proper analysis of Sino-Russian defense cooperation since the end of the Cold War reveals their evolving interdependence as an opposing force to U.S. primacy. In October 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin characterized Sino-Russian ties as “an allied relationship in the full sense of a multifaceted strategic partnership.” Both sides, however, deliberately avoid terms associated with a formal military alliance, which they view as constraining agreements that hinder sovereign state maneuverability. In his 2019 article, “On the Verge of an Alliance: Contemporary China-Russia Military Cooperation,” in the journal Asian Security, Alexander Korolev performed a quantitative analysis of the Sino-Russian relationship. He categorized alliance formation into two sequential stages: moderate institutionalization and deep institutionalization. Moderate institutionalization includes alliance, treaty or agreement; mechanisms of regular consultations; military-technical cooperation and military personnel exchange; regular military drills; and confidence-building measures.

The 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation provided the groundwork for the moderate institutionalization of the Sino-Russian relationship after the Cold War. However, the Big Treaty, as it is also called, does not explicitly define external threats nor include a clear casus foederis clause (similar to NATO’s Article V), and therefore fails to qualify as a defense pact. Nevertheless, Korolev’s data shows a highly institutionalized and upwardly incremental trend of moderate institutionalization between 1992 and 2016 and concludes that China and Russia have surpassed the first stage of moderate institutionalization and entered into deep institutionalization. At the time of his writing, deep institutionalization — including integrated military command, joint troops placement and/or military base exchange, and common defense policy — had not been assessed, but they have “created strong institutional foundations for an alliance, and now only minor steps are necessary for a formal and functioning military alliance to materialize.” More important, Korolev argues “that China and Russia are willing to accept a degree of strategic vulnerability to sustain cooperation, committing the bulk of their resources to counter the U.S. separately in their respective contests.”

The 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation provided the groundwork for the moderate institutionalization of the Sino-Russian relationship after the Cold War. However, the Big Treaty, as it is also called, does not explicitly define external threats nor include a clear casus foederis clause (similar to NATO’s Article V), and therefore fails to qualify as a defense pact. Nevertheless, Korolev’s data shows a highly institutionalized and upwardly incremental trend of moderate institutionalization between 1992 and 2016 and concludes that China and Russia have surpassed the first stage of moderate institutionalization and entered into deep institutionalization. At the time of his writing, deep institutionalization — including integrated military command, joint troops placement and/or military base exchange, and common defense policy — had not been assessed, but they have “created strong institutional foundations for an alliance, and now only minor steps are necessary for a formal and functioning military alliance to materialize.” More important, Korolev argues “that China and Russia are willing to accept a degree of strategic vulnerability to sustain cooperation, committing the bulk of their resources to counter the U.S. separately in their respective contests.”

In “The Emperor’s League: Understanding Sino-Russian Defense Cooperation,” published in 2020 on the War on the Rocks website, Michael Kofman believes there are important reasons why the current relationship is not simply transactional but also is unlikely to materialize into a military alliance. He describes how defense transactions that began strong in the 1990s with 25% of total trade between the two nations and peaked in the early 2000s have now declined dramatically, accounting for only 3% of total trade. Thus, the value of transfers has decreased while defense cooperation has increased over the last two decades. Furthermore, he claims the relationship is not a product of recent events but has been developing for over 30 years.

Moscow learned a great deal from the Sino-Soviet split that occurred in the 1960s, which created a second front of competition with China. As a result, contemporary Russian elites now look to China to balance the U.S., while drawing U.S. resources into the Indo-Pacific and further away from vital Russian interests in Europe. Finally, their relative symmetry in military power means that one country does not extend security guarantees, conventional or nuclear, to the other. Russia can contribute very little to China’s cause in the Indo-Pacific, and China’s military presence in Europe is nonexistent. Therefore, Kofman says, the relationship is “best described as an entente, which at a bare minimum can be interpreted as a nonaggression pact.” For it to endure, China and Russia should not contest each other’s vital interests nor support their respective adversaries in key contests. He concludes that the Sino-Russian “strategic partnership” is better understood as a strategy in which the two countries intend to contest the U.S. “together, but separate,” forcing the U.S. to compete on both fronts at the same time. In summary, the partnership in its current form is not an alliance, but a strategic partnership designed to enhance the national interests of the two participants, which Kofman argues can have much greater substance than a formally declared alliance.

Drivers for cooperation

In “Navigating Sino-Russian Defense Cooperation,” also published in 2020 on War on the Rocks, Kendall-Taylor, et al., identify two sets of drivers that are likely to facilitate deeper cooperation. The first driver they identify is a sustained U.S. hard-line approach against both Russia and China. Not simply rhetorical statements, but U.S. actions — both economic and military pressures — have “created a common cause between them.” Beginning in 2014, the West imposed heavy sanctions on Russia as a result of its illegal annexation of Crimea and occupation of southeastern Ukraine. These measures effectively closed the door to Russian cooperation with the West and increased Russia’s dependency on China. Furthermore, U.S. presence on both of their peripheries presents the U.S. as the common enemy missing from the Big Treaty. Their mutual intent to counter U.S. regional presence is evident by the first-ever Sino-Russian joint air patrols of the Indo-Pacific in 2019. Additionally, in 2018, China deployed its first Russian-made S-400 air defense system to counter U.S. air and naval power in the Pacific.

Second, Russia and China have complementary needs and capabilities that they can leverage to individually elevate national great-power aspirations. Russia provides arms sales, operational military expertise and energy, while China provides markets for arms sales and capital for investment in Russian technology. Kendall-Taylor, et al., estimate Russian arms sales to China in the 1990s at $5 billion to $7 billion and at $40 billion in the mid-2000s. Russia also has extensive and recent operational military experience in Syria and Ukraine. China’s military — though bolstered through Russian arms sales — remains largely untested. China has sent thousands of service members to study in Russian military institutions and has increased the frequency and scope of joint exercises since 2005. On the other hand, China’s booming economy provides capital to boost Russian technology and purchase energy and military equipment that U.S. sanctions have prevented Russia from selling elsewhere. Given the current vector of Sino-Russian defense cooperation, these drivers (no doubt more necessary for Russia than China) are largely induced by U.S. policies and seem to outweigh their historical mistrust of one another.

Limitations of Sino-Russian defense cooperation

Though Sino-Russian defense cooperation continues to grow more complex, the relationship also faces fundamental limitations. Historic mistrust, a lack of cultural consonance, intellectual property theft and the growing asymmetry between the two nations are the most apparent barriers to further cooperation. However, in spite of these, their top-driven relationship allows them to continue to deconflict in key regions and, so far, has not prevented strategic cooperation. Russia continues to sell sophisticated weapons to China, suggesting that Russian concerns over property theft and distrust can be overcome. What may not be overcome are their drastically diverging views (and practices) on world order, as Marcin Kaczmarski describes in his 2019 article “Convergence or Divergence? Visions of World Order and the Russian-Chinese Relationship” in the journal European Politics and Society. China focuses more on the economic sphere and depicts itself as the locomotor of globalization. It prefers an incremental shift in international arrangements that will empower Beijing versus an abrupt change in the world order that would undermine general political stability or harm economic openness. Russia, on the other hand, sees itself as a great power in opposition to U.S. dominance and does not consider the current world order beneficial to its great power interests. Therefore, Russia appears determined to regain its privileged position in a short period of time with the use of its renewed military capabilities and seeks to stoke an anti-globalist agenda and exploit international turmoil to enhance its own position. To put it bluntly, China needs international stability more than Russia does.

Kaczmarski claims that their individual approaches to global security governance diverge as well. Russia compensates for its economic weakness with intensified political-diplomatic activity and involvement in international crises. Take the Syrian civil war for example: Russia intervened in support of the Bashar Assad regime while China maintained a relatively low profile in spite of its growing military capabilities and global ambitions. Furthermore, Russia’s conflict in eastern Ukraine and annexation of Crimea have practically eliminated the possibility of making Ukraine part of China’s Belt and Road program. Conversely, Russia’s continued arms sales to countries in Southeast Asia (Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia) infringe on China’s territorial interests in the South China Sea. In addition to conflicting regional endeavors, both countries’ defense industries and military establishments are largely autarkic and deeply nationalistic and to a certain degree see one another as a military threat. Therefore, they will not enthusiastically jump at opportunities for co-development and deeper cooperation. Domestic stakeholders desire to keep procurement spending for themselves, and both China and Russia have an overwhelming desire for self-sufficiency. Lastly, their threat perception of one another is captured by Franz-Stefan Gady of the EastWest Institute in “China-Russia: The Entente Cordiale of the 21st Century?” in which he states that “Russia’s decision to abandon the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was partially influenced by China’s growing ground-based medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missile arsenal.” Despite friction, even at the highest levels of national strategy, Sino-Russian defense cooperation continues to progress, and the implications of deepening cooperation could have grave consequences for the U.S.

Implications of deepening cooperation

Regardless of alliance formation, Sino-Russian defense cooperation has the potential to create significant challenges for the U.S. over the next five to 10 years. In particular, their greater alignment will elevate the challenges that China poses to the U.S. Kendall-Taylor, et al., and Kofman inform four intertwined and wide-ranging categories of consequences: 1) facilitating each country’s ability to project power; 2) eroding U.S. military advantages in the Indo-Pacific; 3) research and development cooperation leading to technology advancements; and 4) complicating U.S. defense plans and capacity. First, Sino-Russian defense cooperation amplifies joint power projection. Two joint exercises in 2019 — the Indo-Pacific strategic bomber patrols and Indian Ocean naval maneuvers with Iran — had three effects. They signaled political convergence and willingness to push back against U.S. regional influence; they aimed to undermine U.S. dominance and deter future U.S. interventions; and they allowed competitors such as Iran to increase their power projection and force U.S. strategists to consider new regional scenarios. As a result, this sustained coordination accelerates efforts to erode U.S. military advantages, which is especially problematic for the U.S. in its competition with China in the Indo-Pacific. For the last three decades, Russia has provided China with advanced area-denial weapons systems and aircraft to counter U.S. air and naval power in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. In addition to military hardware and cooperative development, Russia has provided China with valuable operational experience, offsetting their most significant weakness relative to the U.S. These cooperative developments put at risk America’s ability to deter Chinese aggression and uphold its commitment to maintaining a free and open Indo-Pacific.

In terms of technology advancements, Sino-Russian research and development cooperation could allow them to collectively outpace the U.S. in this arena. Russian technological innovation coupled with Chinese capital not only obviates U.S. sanctions and restrictions on technology exports, but it creates tough competition for the U.S. This cooperation is evident in counterspace capabilities, hypersonic weapons and submarine technology, and challenges the U.S. technological edge in these domains. Finally, overt Sino-Russian defense cooperation has the potential to complicate U.S. defense plans and capacity. Defense cooperation has become more formalized and has crept into sensitive sectors considered to be strategic in nature. This is most evident in the global warfighting domains, such as space and cyberspace, where one state could sabotage or degrade a U.S. response to a contingency. A more dangerous, albeit less likely, scenario would be a coordinated two-front action with concurrent moves into Eastern Europe and across the Taiwan Strait. In the current environment, the U.S. would be hard-pressed to respond on a single front, let alone two simultaneously. Such a scenario would require resources akin to World War II, but on a modern scale — a scenario for which the U.S. is not prepared, with fragile alliances and defense assets spread so thinly across the globe.

The democracy delusion

While China and Russia have grown strategically closer over the past 30 years, what has the U.S. been doing? In “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy” in Foreign Affairs magazine in 2016, John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt describe how the U.S., after emerging from the Cold War as the world leader, set out to promote a world order based on international institutions, representative governments, open markets and respect for human rights. They argue that this strategy quickly evolved into the U.S. assuming the role of “the indispensable nation,” where it has the “right, responsibility, and wisdom to manage local politics almost everywhere.” When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, President George H.W. Bush responded, as Iraq threatened to place Saudi Arabia and other Gulf oil producers at risk. But he refrained from advancing on Baghdad, and the succeeding administration of President Bill Clinton should have moved back offshore to allow Iraq and Iran to balance themselves. Instead, his policy of “dual containment” kept U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia to check the regional actors simultaneously.

China is increasingly challenging the status quo not only in regional waters, but throughout the globe. Russia is determined to restore the old Soviet sphere of influence through provocation and proxy wars. Furthermore, both countries have strategically liberated one another to pursue their respective interests without reprisal from the other. Elsewhere, the world has witnessed expanding nuclear arsenals in India, Pakistan and North Korea.

Is it too late?

Initial analysis of the foreign policy of the new administration of U.S. President Joe Biden was discussed during the Russia Hybrid Seminar Series hosted by the Marshall Center in February 2021. At first glance, the Biden administration appears to be erasing the last four years of former President Donald Trump’s “America First” strategy. But like his predecessor, Biden prioritizes long-term strategic competition with China over Russia, and the greatest determinant in his foreign policy toward great power competition will be on the Sino-Russian partnership. Given that trying to drive a wedge between China and Russia just drives them closer together, the Biden administration may seek a deal with China — by decreasing confrontation and reducing the utility in Beijing of closer relations with Russia. Conversely, if the U.S.-China confrontation were to continue, then it is likely that the Sino-Russian partnership would grow.

Regarding Russia, the new administration will likely be focused on rebuilding the trans-Atlantic relationship, involving coordination with European allies on Russia policy. Within the first three weeks of taking office, Biden agreed to a five-year extension of the New START Treaty and the negotiation of a replacement treaty. However, arms control notwithstanding, there are few opportunities for improvement given the extent of recent confrontation. Relations with Russia simply cannot deteriorate any further without armed conflict. As Putin himself has said, “You can’t spoil a spoiled relationship.” Yet, aside from the U.S.-China-Russia triangle, Biden speaks about tackling domestic challenges, beginning with the nation’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the partisan politics affecting U.S. policies. The emphasis on domestic issues may be the determining factor and best strategy for countering the Sino-Russian strategic partnership in the long term.

Conclusion: A return to offshore balancing

American prosperity flourished over the course of the 20th century largely due to the concepts of offshore balancing. U.S. participation in both World Wars exemplified such a strategy — that is, it only became involved when Europe could not contain Germany. After World War II, it was apparent that a war-torn Europe could not defend itself against the Soviet Union. Therefore, the U.S. built and maintained forces in Europe throughout the Cold War, following the basic premise of offshore balancing: becoming involved only when regional allies are incapable of countering regional hegemons. After the Soviet Union collapsed, ending the Cold War, Europe no longer had a dominant power and Mearsheimer and Walt argue that the U.S. should have slowly withdrawn forces, cultivated amicable relations with Russia, and handed European security over to the Europeans.

In the context of the China-Russia problem, an offshore balancing strategy provides a more sustainable and collective approach to U.S. grand strategy. French Ambassador to the U.S. Jean-Jules Jusserand (1902-1924) once said, “On the north, she has a weak neighbor; on the south, another weak neighbor; on the east, fish, and the west, fish.” America is blessed with a unique geopolitical posture that allows it to pursue such a strategy. First, offshore balancing calls for the optimization of defense posturing and expenditures by viewing them through the lens of national interests. This strategy prioritizes national interests and only commits resources offshore when vital interests are threatened, thereby reducing areas the U.S. military is committed to defend, and forces other nations to pull their own weight. Thus, offshore balancing not only reduces resources devoted to defense, but allows for greater investment and consumption at home and puts fewer American lives in harm’s way. Second, offshore balancing leverages regional allies to maintain global security. Instead of providing the bulk of deterrent forces and capabilities, the U.S. will empower its allies’ abilities to do so through international institutions, diplomacy, economic support and military capabilities, if necessary. By empowering allies, U.S. primacy as the impetus of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership is obscured by a network of equally contributing stakeholders bound together by liberal democratic values. Therefore, offshore balancing requires not only a serious assessment of national interests, but a strong network of alliances, which must be rebuilt based on trust and compromise rather than U.S. domination. Offshore balancing provides that trust by allowing allies to handle their own affairs with affirmation that the U.S. has their support in times of crisis. Finally, without a single common enemy — the U.S. — the Sino-Russian partnership is likely to unravel.

In his 2011 book, “On China,” Henry Kissinger relates the Western tradition of strategy to a game of chess, where the objective is to achieve total victory over one’s opponent. On the other hand, the Chinese tradition of strategy more closely emulates wei qi, a board game whose objective is to employ a protracted campaign of encirclement. It’s time for the U.S. to step up and play the long game. Given the explosive rise of China, leveraging allies — the basis of offshore balancing — is the only way to do it. Acknowledging that U.S. allies in the Indo-Pacific are too weak and too disparate to counter China alone, perhaps the U.S. should be the “indispensable nation” in the Indo-Pacific. In this instance, the U.S. should go onshore to lead regional allies — Japan, South Korea, India and Australia — through multilateral alliances similar to how the U.S. led NATO during the Cold War.

In Europe, as Mearsheimer and Walt proclaim, the time has come to hand European security over to the Europeans. In fact, European leaders are beginning to recognize this shift as well. At the 2021 Munich Security Conference, French President Emmanuel Macron called for “Europe’s ‘strategic autonomy,’ which would require the Continent to be prepared to defend itself.” A bold statement indeed, but an abrupt reduction of U.S. troops in Europe is not the answer either. A forward presence of permanent or rotational U.S. forces is necessary for NATO solidarity as well as crisis management in adjacent theaters. However, crisis management in Europe and lead roles in the NATO Enhanced Forward Presence, air policing missions and large-scale exercises should be largely transferred to NATO’s European stakeholders. In Southwest Asia, the U.S. should unequivocally withdraw troops and empower regional allies through nonmilitary instruments of power to balance the region.

Comments are closed.