European disunity allows Russia to manipulate gas pricing

By Ion A. Iftimie, Marshall Center alumnus

In 2014, Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, placed the resiliency of a European Energy Union among his top three priorities for the member states. “We need to pool our resources, combine our infrastructures and unite our negotiating power vis-à-vis third countries” from the East, he announced in July 2014, stating his political intentions for the next European Commission. Not coincidentally, Juncker’s comment came two months after the newly drafted European Energy Security Strategy listed “improving coordination of national energy policies and speaking with one voice in external energy policy” as one of the “eight key pillars that together promote closer cooperation beneficial for all member states.”

Under this key pillar, “a particular area of interest is gas, where increased EU political level engagement with prospective supplier countries would pave the way for commercial deals without jeopardizing the further development of a competitive EU internal market. In addition, in certain cases, aggregating demand could increase the EU bargaining power,” the strategy states. But when it comes to a common plan for the Energy Union, European Union Energy Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič noted in February 2015 that “Central and Eastern European countries — largely dependent on Russian imports and having had some ‘bad experience’ — are keener on the plan than Western EU members, who have seen no market disturbance and are paying lower import prices,” The Associated Press reported.

While the Energy Security Strategy recognizes the continent’s dependence on Russian natural gas, it offers no real solutions other than increasing imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Furthermore, despite Šefčovič’s new common plan for the Energy Union, Europe lacks a strategy to grapple with Russia’s natural gas pricing schemes and supply disruption threats to re-establish influence in Eastern and Central Europe. As noted in an INSS Strategic Forum in 2011: “At best, Europe must live with continuing energy insecurity; at worst, a total breakdown of negotiations between the supplier [Russia] and transit country [Ukraine] could leave many European countries without heat or electricity.” Both options are unacceptable scenarios for the EU, and this article suggests that a robust Energy Union cannot be realized without the cooperation of all EU member states.

While the Energy Security Strategy recognizes the continent’s dependence on Russian natural gas, it offers no real solutions other than increasing imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Furthermore, despite Šefčovič’s new common plan for the Energy Union, Europe lacks a strategy to grapple with Russia’s natural gas pricing schemes and supply disruption threats to re-establish influence in Eastern and Central Europe. As noted in an INSS Strategic Forum in 2011: “At best, Europe must live with continuing energy insecurity; at worst, a total breakdown of negotiations between the supplier [Russia] and transit country [Ukraine] could leave many European countries without heat or electricity.” Both options are unacceptable scenarios for the EU, and this article suggests that a robust Energy Union cannot be realized without the cooperation of all EU member states.

Geography of natural gas dependency

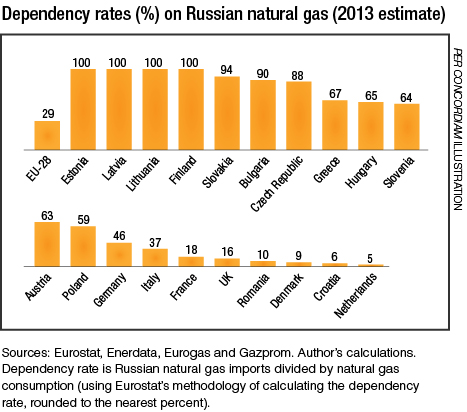

Reducing natural gas reliance is a top priority of the Energy Security Strategy because the EU is 65.2 percent dependent on imported gas. Furthermore, seven EU member states — Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia — rely almost entirely on gas from Russia, which supplies at least 85 percent of these countries’ domestic natural gas consumption. These seven nations surpass, by at least 5 percent, Daniel W. Drezner’s energy dependence threshold outlined in his book, The Sanctions Paradox: Economic Statecraft and International Relations. It states that countries relying on a single supplier for more than 80 percent of their energy demands are more susceptible to coercion. This situation allows Russia to unilaterally set the price of natural gas without significant blowback from these EU member states.

The dependence on Russian natural gas of developed Western European nations differs significantly from that of developing Eastern and Central Europe and the Baltic states in two geographic respects: (1) proximity to Russia — the closer the nation, the more likely it is to be connected to Russian natural gas infrastructure and exports, and (2) access to affordable LNG supplies. Unlike the situation in Finland, the Baltic states, and Eastern and Central Europe, no one country holds a monopoly on natural gas piped to Western Europe. Furthermore, 21 operational LNG regasification terminals — a total of 191 billion cubic meters (bcm) in LNG import capacity — are located across eight countries, Eurogas reports. Together with an additional 65 bcm in LNG import capacity to be built over the next decade, LNG imports to Europe could make up a third of the 618 bcm of natural gas projected to be imported by continental Europe in 2030. Nevertheless, statistics indicate that by 2030, the Russian share of EU net imports could reach between 60 and 83 percent because member states might prefer unreliable, yet cheap, Russian gas to reliable, yet expensive, LNG imports.

Opposition voices

Contrary to the belief that Europe will become hostage to a large energy supplier, two academics view the threat as exaggerated. “Has the dependence on Russian gas given Moscow political leverage over countries to the West? There is little sign of this,” Harvard University professor Andrei Shleifer and University of California, Los Angeles, professor Daniel Treisman wrote in Foreign Affairs in 2011. The two scholars argued that there is little evidence to suggest “a more sinister design in the Kremlin’s foreign policy — to re-impose Russian hegemony over the former Soviet states, and perhaps an even greater portion of Eastern Europe, by means of economic and military pressure.” Their main argument, made prior to the Russian annexation of Crimea, was an economic one — that Russia needs to sell its gas to Europe more than Europe needs to buy it.

“It is Russia’s dependence on the European market — and not the other way around — that is most striking. Europe, including the Baltic States, is the destination for about 67 percent of Russia’s gas exports (other former Soviet countries buy the other 33 percent) … Given the extent to which Russia’s income and budget depend on this trade, losing its European clients would be a calamity.”

Shleifer and Treisman argue that the LNG market and the shale gas revolution knocked Russia’s gas industry “off balance”— a view shared by various EU officials. Former U.S. Undersecretary of Energy John Deutch wrote in 2011 that the results of the natural gas revolution will be that “countries that export large amounts of natural gas will suffer from lower than expected revenues and a reduced ability to use energy as a tool of foreign policy.”

Likewise, a multitude of journalists, scholars, and scientists have written articles suggesting that decreased reliance on Middle Eastern resources could in fact enhance each region’s energy security. “Natural gas is not being affected by the global-geopolitical winds,” Christine Birkner wrote in Futures magazine. In Europe, the interpretation of data by these policy scholars could not be further from the truth.

Problems with opposing arguments

First, Shleifer and Treisman are incorrect in their assessment that Russia needs to sell its gas to Europe more than Europe needs to buy it. As illustrated in the EU Energy Security Strategy, Europe does not have a united energy policy and does not yet have a fully integrated energy market and infrastructure. In energy trade relations with Russia, each EU member state must be examined independently, which reveals that the Baltic states and many Eastern and Central Europe countries need to import Russian natural gas more than Russia needs to sell it to them.

For example, 90.3 percent of Bulgaria’s natural gas comes from Russia, but that amounts to only 1.2 percent of total Russian natural gas exports. If Russia decided to cut the supply of natural gas to Bulgaria, Bulgarians would greatly suffer, while Russia would simply recoup its losses by slightly increasing its natural gas exports to other European nations.

Second, the LNG market and the shale gas revolution did nothing to knock Russia’s gas industry off balance, as Shleifer and Treisman argued. Within the EU, LNG is available mostly to Western European nations. The 21 operational LNG regasification terminals are in Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom. If Greece is counted as part of Eastern and Central Europe, then the Revithoussa LNG Terminal, with a capacity of 5.3 bcm per year, is the only operational LNG regasification terminal in that part of Europe. Furthermore, the two other LNG projects in Eastern and Central Europe being considered were initiated by the two Eastern and Central European countries that are least dependent on natural gas imports, Romania and Poland, representing only 2.3 percent of natural gas that will be imported to continental Europe by 2020.

The Swinoujscie LNG terminal could supply Poland with 7.5 bcm per year by 2018, while the Azerbaijan-Georgia-Romania Interconnector would supply Romania with 8 bcm per year. The remaining Eastern and Central European nations would stay almost entirely dependent on Russian gas. Even in those states with access to LNG terminals, the high costs of transporting LNG makes Russian gas more affordable, despite its unreliability. The Revithoussa LNG Terminal, for example, only processes between 0.51 and 0.68 bcm annually of its 5.3 bcm capacity, and Greece’s dependency ratio on Russian natural gas was still 67.5 percent as of 2013.

Geopolitics of natural gas

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln prophetically warned that the U.S. was becoming a house divided, emphasizing that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” In 2011, then-EU Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger said “the energy challenge is one of the greatest tests” for the EU, primarily because of the lack of agreement on a common plan among member states.

While Russian natural gas imports represent 28.7 percent of the EU’s natural gas consumption — less than 7 percent of the EU’s overall energy consumption — it also represents 66.1 percent of Russia’s overall natural gas exports. Simple arithmetic dictates that a complete shutoff of Russian natural gas to Europe would hurt the Russian economy more than the EU’s economy, but it would also bankrupt the industry of the Baltic states, Finland and most Eastern and Central Europe countries. Because the price they would pay is significantly higher, these nations are less likely to stand united with the West against Russia beyond just words. In such cases, Russia would need only to find a reason to renegotiate the price of natural gas with these nations to silence them. Because of natural gas pipeline politics, the EU remains divided between East and West.

But these divisions between the center and the periphery of the EU — between old and new Europe — originate in the history and the geography of the Eurasian supercontinent. Nations such as Germany and France have historically carried out bilateral relations with Russia on equal footing, while conducting business with the countries in between from a position of superiority. Diana Bozhilova, a postdoctoral research fellow at the London School of Economics, explains this type of relationship, which continues at different echelons today, by the fact that the EU’s center — broadly composed of Western European countries — has more experience dealing with Russia than Eastern and Central Europe:

“Old Europe … is relatively more experienced with international high politics through the conduct of two world wars. Moreover, there exist historical elements of equality in the internationalization of their respective relationships with both the former USSR and Russia throughout much of the twentieth century. As a result, their ‘knowledge’ of and experience with bilateral relations with Russia is invariably greater than that occurring between the CEECs and Russia.”

Both Russia and the European center continue to see international politics as “a series of tête-à-têtes between great powers,” Mark Leonard and Nicu Popescu wrote in a 2007 European Council on Foreign Relations article. They seduce each other with economic incentives in spite of the political consequences to the countries in between — which more often than not are viewed as “costly distractions,” Edward Lucas wrote in his 2008 book The New Cold War: Putin’s Russia and the Threat to the West. This is particularly true of Russia’s relationship with Germany, where the emergence of Russia as a more assertive player in international relations coincided with improved dynamics in political and economic relations between the two nations.

Despite fighting two world wars against each other, Russia’s special relationship with Germany dates back to the 18th century, when Russian Czaress Catherine the Great allowed German nobles to control the Baltic provinces and encouraged German farmers to inhabit the Volga basin. Economic and political ties continued to strengthen in prerevolutionary Russia, when royal families intermarried and Germany invested plenty of capital in Russia. This historic relationship was renewed after Germany’s reunification, particularly due to eastern Germany’s dependence on Russian natural gas.

In recent years, collaboration on projects such as the construction of Russia’s Nord Stream gas pipeline beneath the Baltic Sea to Germany, a pipeline that is meant to bypass Poland and Ukraine and thus decrease their geostrategic influence, further emphasized that Germany places its relationship with Russia before its relations with other Eastern and Central European nations. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, whom Moscow recruited as CEO of Nord Stream by paying him a substantial salary, personally championed the newfound Russo-German economic alliance by testifying that Germany “must be a partner of Russia if we want to share in the vast raw material reserves in Siberia. The alternative for Russia would be to share these reserves with China,” Daniel Freifeld wrote in his 2009 Foreign Policy article.

Radek Sikorski, then-Polish minister of foreign affairs, compared the new Russo-German relationship and the Nord Stream project to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. That nonaggression treaty between Germany and the Soviet Union at the start of World War II divided Eastern and Central Europe into Soviet and German spheres of influence, allowing each country to annex chunks of Poland.

Russian deception

In its relations with Germany, the Russian leadership, particularly President Vladimir Putin, proved to be masterful at deception. He convinced the German political class that Russia is a reformed regional power and a credible European partner, effectively changing the narrative/rhetoric in the German public sphere from Russia as antagonist threat to Russia as protagonist partner. Ironically, given Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev previously declared that “the highly efficient cooperation between Russia and Germany in the international arena [has benefited] the strengthening of global and regional stability and security,” a 2011 International Affairs article reported.

Throughout the EU, this cognitive dissonance with regard to Russia is to blame for Russia’s military interventions in Ukraine. While Putin provided economic incentives to Germany by opening his country’s markets to German companies — Daimler Chrysler, BMW, Deutsche Bank, etc. — at the same time he took advantage of this friendship to increase his grasp over the Eastern and Central European natural gas market. And, with Germany remaining Russia’s largest market for gas, it is unlikely that Germany will forgo Russia’s economic incentives for the sake of Eastern and Central European anxieties, even though in the long term this economic alliance will cause political disunity within the EU. The lack of political agreement between the old and new Europe, particularly in the field of natural gas, means that Russia increasingly sets the terms of the debate, and many Eastern and Central European member states fear the EU will not support them if Russia uses economic coercion.

Improvements in Russo-German commercial relations have been followed by progress in business relations between Russia and France. The planned sale by France, a NATO member, of Mistral-class warships to Russia also gave birth to a strong Franco-Russian relationship that is best described through the prophetic words of former French President Charles de Gaulle: “for France and Russia to be united means being strong, being separated means being in danger. Indeed, this is an immutable condition from the viewpoint of geographical location, experience and common sense.”

Correspondingly, the French position — despite recent support for economic sanctions against Russia — has been that “close ties with Russia can be regarded not only as a means of augmenting the power of France within the European Union but also the power of Europe itself.”

This close relationship persuaded the two nations to dedicate the names of the year 2010 to each other, according to a 2011 International Affairs article by Marina Arzakanyan and Tatyana Zvereva:

“At the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first-centuries, Russian-French relations with their long traditions became a strong monolith of political, economic, scientific, educational, literary and art affairs. The two states have entered a stage of privileged partnership. This prompted the governments of both countries to declare 2010 the Year of Russia in France and the Year of France in Russia.”

Different approaches to Russia

But Europe’s core alone cannot be blamed for EU divisions. Leonard argued that EU member states were already divided over their relationship with Russia, and Russia is slowly emerging as the victor in its relations with the EU. To prove this point, Leonard divided EU member states into five categories that differentiated each country’s partnership with Russia — particularly with regard to European policies: Trojan horses, strategic partners, friendly pragmatists, frosty pragmatists and new cold warriors. According to Leonard and Popescu:

“ ‘Trojan Horses’ (Cyprus and Greece) who often defend Russian interests in the EU system, and are willing to veto common EU positions; ‘Strategic Partners’ (France, Germany, Italy and Spain) who enjoy a ‘special relationship’ with Russia which occasionally undermines common EU policies; ‘Friendly Pragmatists’ (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia) who maintain a close relationship with Russia and tend to put their business interests above political goals; ‘Frosty Pragmatists’ (Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Romania, Sweden and the United Kingdom) who also focus on business interests but are less afraid than others to speak out against Russian behavior on human rights or other issues; and ‘New Cold Warriors’ (Lithuania and Poland) who have an overtly hostile relationship with Moscow and are willing to use the veto to block EU negotiations with Russia.”

Not surprisingly, in March 2011, then-Lithuanian Energy Minister Arvydas Sekmokas accused Russia of often putting “political and economic pressure” on the Lithuanian government. Looking at 2013 data, Russia did indeed charge the new cold warriors higher natural gas rates than other EU countries for taking steps to break away from Russia’s natural gas monopoly, while Russia’s strategic partners paid significantly less for Russian gas.

Unfortunately, it may take the Baltic states, Finland, and other Eastern and Central European EU member states years, if not decades, to break free from dependence on Russian natural gas, while Europe’s core will continue to enjoy the benefits of cheap natural gas from Putin’s Russia at the expense of the periphery. Ultimately, EU member states must understand that their lack of unity will only contribute to Russia’s grand strategic political goal of weakening the EU’s geostrategic position and asserting Russian control over its traditional sphere of influence. With this in mind, a 2009 report published by the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations concluded that “no magic bullet will rescue Europe from its dependence on Russia for the foreseeable future.”

Conclusion

The EU must consolidate its bargaining power in its natural gas negotiations vis-à-vis Russia, Edward Christie, Pavel Baev, and Volodymyr Golovko wrote for FIW-Research Reports in March 2011. To date, however, this common energy policy “is seriously hampered by member states’ efforts to defend their sovereignty: based on differing energy mixes, differing suppliers, and differing priorities the member states pursue national energy strategies that are only barely compatible with each other. Despite a perceived similarity of the challenges, the member states face and the strategic objectives they ascribe to a common energy policy (security of supply, stable prices, and environmental protection), they nevertheless adhere to national strategies, which make them pull the common energy policy into opposite directions,” according to a 2011 article published by the Center for Applied Policy Research. Ultimately, a divided Europe that does not have a common energy security policy and a strong institution to enforce it, is not only a weak Europe, but also a household whose members represent a liability for the EU.

Zeyno Baran, director of the Center for Eurasian Policy and a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, wrote in a 2007 Washington Quarterly article: “Russia, the European Union’s primary natural gas provider, has deliberately taken advantage of this lack of cohesion to gain favorable energy deals and heighten European dependence on Russian supplies.” Most Eastern and Central European countries — Europe’s periphery — are vulnerable to Russia’s use of natural gas pricing as an instrument of coercion, and they are bound to remain so without the support of Europe’s center: Germany, France and Italy.

While Russia can afford to set the price of natural gas supplies to individual countries because of the asymmetric interdependence in the trade of natural gas between these states and Russia, Russia could not use natural gas pricing as an instrument of coercion against a united Europe. The consolidation of bargaining power in Europe would then mean that Russia needs to export its natural gas to Europe as a whole just as much, if not more than, than Europe as a whole needs to import it from Russia. o

Ion A. Iftimie is the author of Natural Gas as an Instrument of Russian State Power. It appears on NATO’s recommended reading list and was originally published with the Strategic Studies Institute under the pen name Alexander Ghaleb. Westphalia Press, an imprint of the Policy Studies Organization, republished a second edition in 2015 using the author’s actual name.

Comments are closed.