A Look at What the Future May Hold

By Dr. Sari Arho Havrén, Europe-China policy fellow at Mercator Institute of China Studies (MERICS), visiting researcher, University of Helsinki

Photos by The Associated Press

During the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2017, President Xi Jinping introduced a strategic plan to achieve socialist modernization. The plan envisions a country that by 2049 is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious. A midpoint objective was set for 2035. The CCP has since outlined plans for a comprehensive economic restructuring that includes making China one of the most technologically advanced countries, advancing the standard of living with a focus on sustainability, boosting per capita gross domestic product and reducing the gap between urban and rural areas.

Demand would be the primary driver of economic growth under a strategy that aims to strengthen self-reliance. In 2021, the National People’s Congress (NPC) endorsed the 14th Five-Year Plan, covering the years 2021-2025. Its objectives — closing the rural-urban income gap, promoting global leadership in technological innovation and increasing the pace toward low-carbon development — can be found within China Vision 2035. To reach socialist modernization by 2035, China would need to double its economic output, a challenging target considering the slow pace of current economic growth. Additionally, the 2035 goals cannot happen in a vacuum; they are intertwined with the country’s military capabilities and international reach.

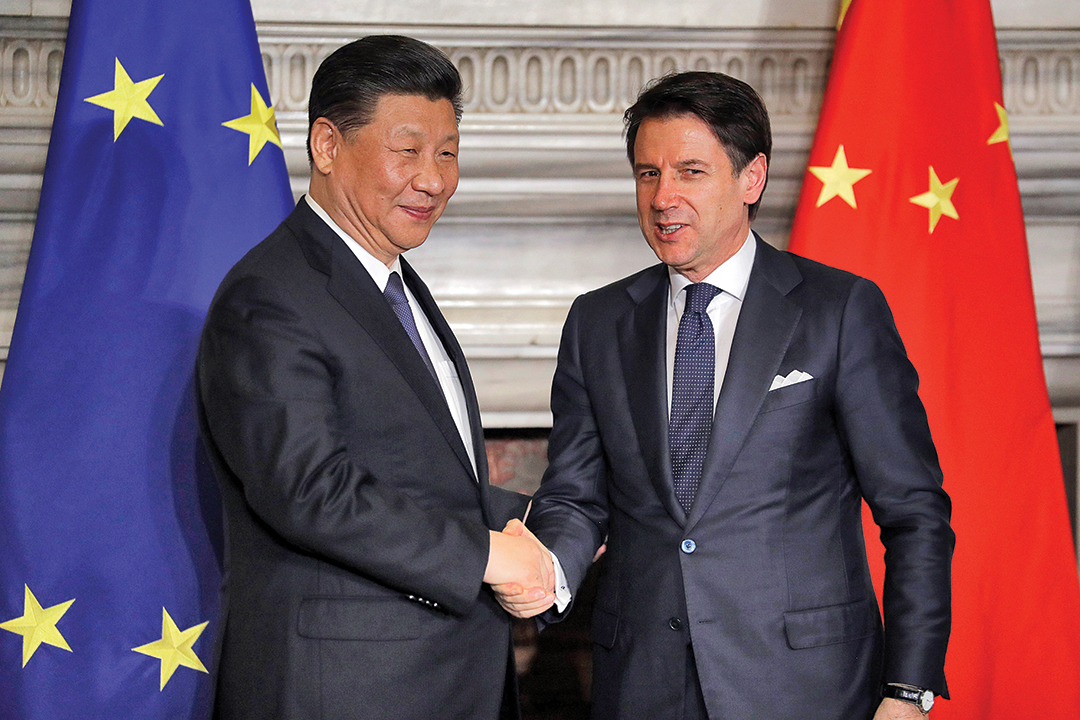

China’s strategy for Europe, or the lack thereof, is hard to pinpoint precisely but could easily be summarized as “divide and rule.” It is in Beijing’s interest to see a weak, divided European Union that is susceptible to China’s efforts to secure its own power base and achieve its 2035 goals. Driving a wedge between trans-Atlantic allies would help China attain its goals. Beijing’s toolkit to influence Europe includes strategic investments, access to the Chinese market as leverage, cultural diplomacy and ambassadors who can be cuddly pandas or aggressive wolf warriors, depending on the situation.

The CCP does not consider the EU a serious institution and thus continues undermining it. Policy papers or reports on China’s intentions in Europe are difficult to find. By contrast, multiple studies are available regarding China’s strategies to displace the United States as the leading nation of the global order. This future-oriented research paper examines China’s strategic long-term intent in Europe in the framework of its global strategic future objectives. It considers two scenarios: China’s influence in Europe strengthens, and China’s influence in Europe diminishes. It looks at various forces, drivers and future signals to shed light on China’s ambitions and what they mean for Europe. Signals, as referenced in this paper, are phenomena that have the capacity to impact or change the future on their own, or when pooled with supporting signals.

Scenario: China’s Influence in Europe Strengthens

The baseline assumption behind this scenario is that Beijing’s core interests and consequent strategies prevent it from making substantial diplomatic compromises, and that EU institutions and its member states are unable to push back in a meaningful manner. In this scenario, Europe has not maintained unity and solidarity, and China has successfully managed to prevent Europeans from forming a common front to counter China.

Signal 1: Common prosperity has replaced economic liberalization and openness as the party ideology.

Wang Huning, considered Xi’s chief strategist, has successfully argued that China must resist “global liberal influence” and has called for “a culturally unified and self-confident nation governed by a strong, centralized party-state” that is “immune to Western liberalism.” Xi is said to share Wang’s thinking. Xi is equally repulsed by commercialization, the new rich and what is perceived as a loss of values. These are seen as deriving from Western liberal capitalism and are considered symbols of decadence and existential threats. Xi wants to direct the nation back onto what he sees as the righteous path with a common prosperity campaign. He has framed the concept of common prosperity as a prominent political issue, not just an economic one. In practice, common prosperity is why Chinese technology giants and video gaming have been targeted by the government, why rent increases have been capped and why being rich is no longer considered glorious.

What does this mean for Europe?

Western liberal culture is increasingly seen as a source of vice and decadence. Making Chinese public opinion immune to Western (including European) soft power would further alienate the cultures and make Europeans appear suspicious and potentially inferior. European high-end consumer brands could become viewed as symbols of exhibitionism, losing their allure. China is already reducing its dependency on the outside world and this can easily spill over to include European brands. More important, China’s moves to educate citizens with socialist core values — and shift the technology talent pool away from gaming and consumer ventures and toward hardcore technologies — makes it easier for Beijing to achieve its goal of being the world’s leader in future technologies, which increases Europe’s dependency on China and widens the technological gap. Leading in technology can allow China to utilize European data sources, opening the way for greater influence over values and opinions, and potentially an increase in surveillance operations.

Signal 2: China has begun to align its domestic development with its international relations.

China’s leadership is expanding its influence and working toward larger goals through the Belt and Road corridors in the Middle East, Africa, Russia, Eastern Europe — and even within the EU. Beijing knows that to achieve its goals it must shift its relations with the world. The CCP claims to be preparing for the new global economic paradigm and is aligning its domestic development not only through Belt and Road, but also through such instruments as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. China has also increased its influence in multilateral organizations and institutions.

Furthermore, China aims to become the world’s leading technological standard-setter. Through China’s influence corridors, the best minds from friendly countries come to Chinese universities and are exposed to nationalistic and patriotic narratives. In addition, according to China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe, a multinational consortium known as CHOICE, China may be targeting youth in Central and Eastern European countries though educational programs.

What does this mean for Europe?

Europe could gradually lose influence in the region while China’s influence could increase within the EU and in its member states. Simultaneously, China has an opportunity — by using soft power or surveillance, intimidation or fake news — to turn public opinion in these areas in support of China’s aims. Another real threat is that China systematically targets the next European generation. As China observer Liisi Karindi writes in an article published on the CHOICE website, “impacting the next generation of talent and leaders means, in essence, buying the future of Europe.”

Signal 3: China’s core interests leave little, if any, room for diplomacy.

Xi has said he will never compromise on China’s sovereignty, security or development interests. He sees Western influence as a risk to national security and warns against the “infiltration of universal values.” Free speech and free press are risks that must be under the CCP’s control. The CCP elite does not see this type of control as a sign of insecurity — as is often the case in the West — but a means to reach policy objectives.

What does this mean for Europe?

China’s ambiguous core interests, together with a perception that democracies are weak and unable to deliver security and prosperity to their citizens, allows it to take a strong position in its international relations. Reasons to negotiate and compromise diminish, and European nations have to accept that China’s core interests are nonnegotiable. Fear of offending Beijing and igniting tensions has already led EU member states and European organizations and companies to yield to Beijing’s pressure. China uses its market access to pressure government and businesses to lobby on its behalf.

Lithuania offers an example of the consequences of crossing China’s interests and of China’s expanding reach. Sovereign countries are challenged to define their foreign policy independently when dealing with China’s interests. In retaliation for Lithuania opening a Taiwanese representative office in Vilnius, China stopped Lithuanian imports and exports by removing Lithuania from its customs list and demanded that multinationals either stop trading with Lithuania or risk losing China’s business. At least one European multinational has submitted to Beijing’s demands, and the German Baltic Chamber of Commerce took Beijing’s side in the schism, according to the South China Morning Post. Other EU member states have been unable to come to Lithuania’s support in any meaningful way, except for the demonstration of solidarity by Estonia and Latvia in withdrawing in August 2022 from the 16 +1 framework established by China. From Beijing’s view, its strategy has worked by testing the EU’s unity and showing that the bloc cannot effectively defend its member states.

Signal 4: China is confident in its own power.

China believes the East is rising and the West is declining. And because China’s image in the West is souring, some scholars suggest that Beijing might think its window of opportunity is shrinking to exploit, for instance, a risky military maneuver against Taiwan. However, very little information out of Beijing would indicate that the CCP’s leaders see themselves in such a narrow vista. Although Western democracies question the relativity of Chinese omnipotence, Chinese leaders remain confident. After all, the 14th Five-Year Plan emphasizes “institutional superiority,” “social stability” and “administrative efficiency.”

China has also been strategic in preparing for future challenges. For example, China already dominates global battery processing even though, domestically, it does not have all the required minerals, such as cobalt and lithium. As a result of the crackdown that limited gaming and e-commerce, and that resulted in layoffs, coders and tech experts are free to work in strategic areas, such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence (AI). The party’s leaders are confident that they can handle critical national challenges, such as inequality, an aging society, climate change, a slowing economy and great power competition.

What does this mean for Europe?

China’s current policies, especially those reining in technology companies and diverting talent from entertainment technology sectors into more strategic and productive economic sectors and manufacturing — to reach 2035 goals — may widen the gap between China and Europe. European policymakers and business owners have been reluctant to form a unified front to counter China. Psychologically, European single economies may fear China’s countermeasures, especially if the EU’s inability to defend Lithuania is seen as a precedent.

Signal 5: China is weakening the structures that maintain the American-led global order while strengthening those of a Chinese alternative.

China prefers bilateral relations with European states over relations with a unified, strong EU. However, China also embraces European strategic autonomy because it sees it as a counterforce to the U.S. and a buffer against its own deteriorating relations with the U.S. Beijing uses traditional divide-and-rule tactics to drive a wedge between the U.S. and its European allies. In March 2021, Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe visited four European countries, including Hungary and Greece — two EU member states that are also NATO allies — and boldly suggested including military cooperation in the deepening strategic partnership agenda. China’s state media and its foreign ministry suggest the EU should think about what matters more, its trade with China or its alliance with the U.S. And when the EU acts against Beijing’s interests, Chinese sources claim the EU allows Washington to dictate its foreign policy.

What does this mean for Europe?

Europe plays an essential role here, especially because China wants to gain a more prominent role in international organizations and split Western alliances. Chinese hegemony in the developing world and countries surrounding Europe would further weaken the EU and leave fewer global choices to the EU and its member states both economically and politically.

Signal 6: China’s new data security law forms a legal basis to build a comprehensive global surveillance system.

An amendment to China’s security law defines “national core data” as all data concerning national security, the national economy, people’s livelihoods and significant public interests. It reads: “When data handling activities outside the mainland territory of the PRC harm the national security, the public interest, or the lawful rights and interests of citizens or organizations of the PRC, legal liability is to be pursued according to the law.” As is common with other Chinese laws, this one is ambiguous by not defining when one actually crosses a line.

The technological surveillance system has been extensively tested and used in China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The outcome encouraged the extension of AI surveillance across China and beyond. China’s digital infrastructure and the control mechanisms are almost limitless. The system can control people throughout the world like nothing before. China has been exporting its surveillance technology to multiple autocracies and weak states worldwide. It is a matter of time before these technologies will be integrated into one holistic system, to which the CCP eventually has access. In an article in The Atlantic magazine, Deputy Editor Ross Andersen wrote that the “emergence of an AI-powered authoritarian bloc led by China could warp the geopolitics of this century. It could prevent billions of people, across large swaths of the globe, from ever securing any measure of political freedom.”

What does this mean for Europe?

Andersen quoted an official who worked in the administration of former U.S. President Donald Trump who warned of the consequences of failing to lead in emerging technologies. China is well on its way to acquiring enormous amounts of user data from foreign citizens and integrating it into government databases. The Chinese technology company Alibaba has been tasked with building the AI-powered software City Brain, a sort of nerve center. These steps will enable future forms of integrated surveillance. Anderson gives examples of how the Chinese government could harvest data: through automobile cameras creating 3D models of cities, through drones collecting data to identify people and through technology that might one day read people’s thoughts. Once these technologies are integrated, an authoritarian government has enormous opportunities to control its use. It is practically impossible to prevent this from happening because Chinese firms and foreign firms operating in China are legally required to assist the Chinese government. Eventually, all information, buying habits, communications, connections, health data and DNA could be synergized. In Europe, Huawei has built research sites known as innovation centers in multiple cities, and in Serbia it is building a surveillance system aimed at detecting crimes.

Meanwhile, the race for talent intensifies. Huawei established an innovation center in Finland with local universities to tap into the Finnish engineering talent pool. The Chinese technology company Baidu has publicly signaled that the top talent pool for AI can be found in the West. If China can surpass the U.S. in technology and in the AI race, it will strengthen its geopolitical power.

Signal 7: China does not accept the EU defining it as a rival.

China points to the EU’s 2019 China Policy document, which describes China as a partner, a competitor and a systemic rival. Wang Yi, China’s minister for foreign affairs, has repeatedly expressed China’s discontent with the EU, referring to it as a systemic rival. Chinese envoys have since adopted this narrative. For instance, Ambassador Zhang Ming, head of the Chinese mission to the EU, has said that labeling China a rival is a misjudgment of EU-China relations and creates barriers. China has pressured the EU and member states to stop using the term rival. The Chinese mission to the EU claims that European businesses want to separate economic interests from political interests and therefore do not want to define China as a rival.

What does this mean for Europe?

Pressure, demands, and carrots and sticks influence vulnerable EU member states. China is using both sweet talk and brutal criticism. Zhang calls China and the EU “responsible major powers,” a wording that undoubtedly pleases EU leaders in their quest to place the bloc as the third multilateral power. On other issues, Beijing is quick to issue stern warnings to the EU and individual member states. For instance, when European Parliament members visited Taiwan, Wang warned that the European countries would pay a price for developing closer ties with Taiwan. These tactics are meant to make European governments wary of losing their access to the Chinese market.

Signal 8: Beijing uses German businesses to lobby on its behalf.

China has multifaceted resources to influence European leaders, policymakers, political parties, lobbyists, industries, universities and media using technology, human resources and other hybrid means. One powerful tool is to use the German business elite to lobby on behalf of Beijing in Germany and in the EU. German industry leaders, such as Volkswagen Group CEO Herbert Diess, have called for more cooperation with China, not less. “It would be very damaging if Germany or the EU wanted to decouple from China,” he wrote on Twitter. Germany’s dependency on the Chinese market is a rare but influential case and a risk to the EU because, as Karindi reports on the CHOICE website, 44% of EU exports to China originate from Germany. In the case of Lithuania, China has evidently used the German connection to pressure the Baltic nation. First, China pressured German automotive parts manufacturer Continental to stop using components made in Lithuania. Soon after, the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce warned that plants in Lithuania with German investors may close unless Lithuanian-Chinese relations were restored, giving the appearance that Germany’s business elite is being pressured to act on China’s behalf.

Elite capture in Europe goes beyond businesses. Beijing also sends envoys to Europe to meet with China-friendly scholars and politicians. In Greece, for instance, a Chinese representative’s talk about “contributing the wisdom of ancient Eastern and Western civilizations to building a community with a shared future for mankind” was well received by Greek elites, according to a Carnegie Endowment paper. Even young future elites don’t go unnoticed. They are presented with educational opportunities and then profitable business deals. For Hungarian journalists and academics, Beijing offers study tours and opportunities for scholarship programs. In return, the alumni are expected to advocate for closer political, commercial and cultural ties.

What does this mean for Europe?

Beijing’s pressure on individuals and businesses shapes the behavior of these actors. Multinational corporations find it easier to succumb, self-censor and adjust rather than risk losing access to the Chinese market. In return, Beijing rewards them with some positive policy changes, such as the recent removal of limits on foreign ownership of passenger car manufacturers. All these actions strengthen the symbiosis between German multinationals and the PRC, which in turn translates into more intensified lobbying in Europe to advance relations with the Chinese government.

Signal 9: China focuses on Europe instead of the U.S. in science, technology and innovation.

China’s economic influence in Europe is significant, especially in Germany, and it successfully uses that influence as leverage. At the same time, China needs access to European technology, markets and universities, mainly because it is a long way from becoming self-reliant in all technology verticals, such as semiconductors, advanced machinery and in some digital fields. In addition to increasing its spending on research and development to become the world leader in science, technology and innovation by 2050, and in AI by 2030, China must seek international cooperation to access these critical technologies abroad.

What does this mean for Europe?

Europe lacks the legislation, regulations and means to identify problematic ties with Chinese influence operations and research collaboration. European parties are not equipped to even notice when their technologies are transferred and used in sensitive areas, such as contributing to human right abuses or dual-use technology purposes.

Germany is the largest European investor in China, according to a study by the China International Promotion Agency. China can use trade and investment dependencies to its advantage (an example being Chinese diplomats hinting of consequences unless Germany accepted Huawei’s 5G technology).

Certain Chinese investors will be mandated to invest in strategic assets in Europe. These investors will primarily be state-owned enterprises with funds and access to offshore capital, according to the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm. The desired investment targets include high-tech, commodities and infrastructure investments that China needs to achieve its 2035 goals. The Rhodium Group forecasts that under “current circumstances it is most likely that Chinese buyers will target small- and medium-size technology firms in countries with less robust screening systems and relatively friendly relations with China.”

That puts Europe in a vulnerable position because the U.S. has made it more difficult for Chinese entities to operate there. Northern Europe has become a focus of China’s interest because of their open economies and dependence on foreign trade.

Signal 10: Western democracy is seen as an enemy.

U.S. President Joe Biden’s Summit for Democracy in December 2021, and the inclusion of Taiwan as a participant, sparked a fierce response from Beijing that included a counterconference on democracy and a campaign that sought to convince the world that China’s governance model represents a superior form of democracy. China’s aim to redefine democracy is not a new phenomenon, but its efforts intensified in 2021, partly because democracies have been weakened. China has taken advantage of the circumstances. It has also had some success in convincing people around the world that its model is superior.

What does this mean for Europe?

China’s actions blur the definition of democracy and aim to convince people at home and abroad that China’s alternative model of governance is superior to Western democracies. This, in turn, allows China to justify its authoritarian model of governance and rule. All these actions fall on fertile territory in Europe, where disinformation and misinformation campaigns by various state and nonstate actors, including Chinese, have weakened social media literacy skills.

Scenario: China’s Influence in Europe Decreases

The research here concentrates on signals deriving from China’s policy initiatives, guidelines and internal developments in various areas that impact Europe. Signals that point toward pushback or countering China’s actions by the EU or member states are not covered.

Signal 1: Beijing may reconsider its Belt and Road commitments.

China’s foreign investment levels have declined since 2016 and many expected benefits have not materialized. According to Elizabeth Economy, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, a review of the top 10 recipients of Belt and Road investments reveals that the level of investment does not directly correlate to the recipient country’s support for China on critical issues. Instead, China must resort to coercion to achieve its goals.

China’s shrinking economy, partly impacted by COVID-19, has forced the country to reduce Belt and Road projects. As reported by Business Standard magazine, investments dropped 54% in one year. And the overall slowing of the economy has caused Beijing to tighten its fiscal policies, which could lead to further slowdowns on Belt and Road projects.

What does this mean for Europe?

China will likely turn its attention away from Europe and toward fulfilling its current projects elsewhere. For instance, in Pakistan, only 32 of 122 Belt and Road projects have been completed, according to Business Standard. Because Belt and Road is China’s central policy tool for expanding its international influence and connectivity, Europe has time to push its own initiative, the Global Gateway. With its 300 billion euro infrastructure budget, the EU could strengthen its supply chains and trade, especially in strategic geographies in Europe and, for instance, Africa.

Signal 2: China’s hubris is not based in reality.

The Chinese government has shown almost dangerous overconfidence in its ability to take over the world. Economy, the Hoover Institution senior fellow, thinks this excessive pride may prevent CCP leaders from recognizing the resistance and realities abroad and could lead to serious miscalculations in Beijing. It has also been argued that because of internal challenges — an aging population and slowing economy — Beijing might see its window of opportunity narrowing and take unnecessary risks.

What does this mean for Europe?

Any premature risks would likely occur in the Indo-Pacific or internally. Europe would not be the focus of Beijing’s concerns, giving leverage to the EU and its member states to potentially negotiate more equal terms in overall relations with China.

Signal 3: The 17+1 format is stagnating.

China has not delivered on its promises under the 17+1 (or the current 16+1) format, Beijing’s plan to promote business with Central and Eastern European countries. Some Eastern European countries are disappointed that Beijing has not followed up on its promises.

What does this mean for Europe?

Beijing has been using the 17+1 format as one of its tools to divide the EU and to induce the economically weaker European nations to advance its interests in Europe. Considerable stagnation of the format could potentially allow EU member states to form a more unified stance against China.

Signal 4: The focus is primarily on the Indo-Pacific.

Strategically, Beijing aims at freeing Asia from the influence of the U.S. and other Western powers. Xi’s shared community and connectivity plans are centered on China, while other Asian countries are left being China’s subordinates. As China has not been able to cement this vision in the Asia Pacific entirely, it remains possible that Beijing may see a need to concentrate more resources and focus on the area, which the U.S. started pivoting toward during President Barack Obama’s administration.

In China’s view, the U.S. is traditionally an Atlantic power. Although it is in China’s interest to divide Europe and weaken the trans-Atlantic alliance, China might put more emphasis on building a more substantial base in the Indo-Pacific, especially as it relates to Taiwan and the South China Sea nine-dash line.

What does this mean for Europe?

China will see that the cost is too high to try to pull geographically distant Europe into its orbit while its primary targets are closer to home. However, the EU, NATO and many individual EU member states are concerned about China’s actions and rising power in the Indo-Pacific. Thus, this scenario could pull multiple European nations to increase their presence in the Indo-Pacific, which would likely increase China’s counteractions in Europe, at least to some extent.

Signal 5: There is turbulence in Zhongnanhai.

Every now and then, leaks coming out of Beijing suggest that Xi has not cemented his power quite as tightly as he planned. Renowned Xi researcher Willy Wo-Lap Lam has argued that Xi will face substantial opposition in the 20th Party Congress in 2022. Lam suggests that it remains unclear how effectively Xi can reinforce his power among senior party cadres as well as in the People’s Liberation Army, where opposition clearly looms, and whether he can purge these forces that could eventually challenge his supremacy.

What does this mean for Europe?

A potential regime change in Beijing is a wild card that would require multiple preparedness scenarios to understand the potential consequences. In any case, turbulence would follow and Beijing’s influence on Europe would temporarily stall.

Signal 6: China’s economy is under growing pressure.

China’s economy is the source of never-ending speculation. New data restrictions have made it increasingly difficult to understand what is happening with the Chinese economy. Crackdowns on private education and on the technology and property sectors have led analysts to question where China’s next growth engine will come from because consumers alone will not supplement the decade-old growth model of infrastructure investments. The opacity of the Chinese economy and what is happening inside the country create a level of distrust.

COVID-19 and the consequent lockdown of the country had severe economic consequences. At the end of 2021, the Chinese economy suffered from a prolonged property slump, supply chain shocks and weak consumption. Calls for Beijing to support the economy have increased. During 2022, the government is expected to adopt fiscal policy measures, but uncertainty remains.

Conclusion

Accepting the baseline that China aims to replace the U.S. as the global leader would mean that it is in China’s fundamental interests to divide Europe and thereby drive a wedge between trans-Atlantic allies. The future signals presented in this foresight study attest to this strategy’s existence.

The pools of binary opposite signals are naturally inadequate, and arguably multiple other phenomena could have been included in both categories. However, both signal pools paint scenarios that work as a base for strategic preparedness, which is the preferred outcome of foresight activities.

From Beijing’s point of view, only the first scenario is acceptable: China wants to strengthen its influence in Europe, which would serve its overall policy objectives. China aims at eroding the legitimacy of universal human rights while portraying itself as a modern model of governance that can quickly react to the changing global order and foster stability at home.

Based on the signal pool that points toward China’s strengthening influence in Europe, it can be assumed that China’s clout in Europe will have increased by 2035 — provided that the European member states have not been able to unite to counter China’s growing hybrid and multilevel influence actions. Most European countries would still be democracies, but China would require that “Finlandization” and self-censorship become a norm throughout European institutions, academia and governments. Universal human rights would be adjusted to China’s definition of human rights, which would lack, for instance, freedom of speech and civil and political rights. The signal pool that strengthens China’s influence in Europe is stronger than the pool of signals with the opposite impact. However, each signal that would weaken China’s influence is also powerful alone and could turn the trajectory.

Author’s note: This is a scenario-based projection, and no projection is perfect. Therefore, based on the signals and if nothing changes, these are potential outcomes.

Comments are closed.