Why it should concern us all

By Laura Diorella Islas Limiñana, the Standing Group on Organised Crime of the European Consortium for Political Research

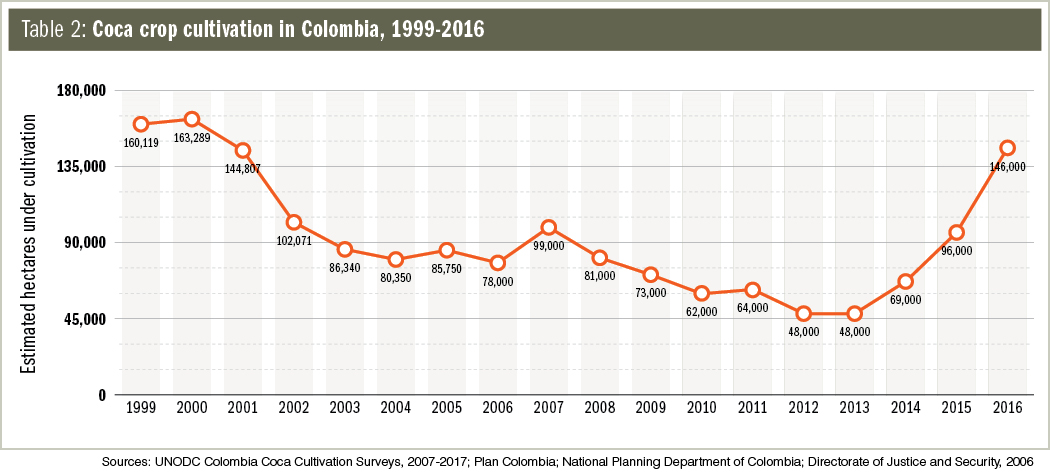

Cocaine production is growing again, despite the exhaustive, combined efforts of governments and the investment of billions of dollars into the fight against drug production and trafficking. In 2015, Colombia reported an estimated 140,000-plus hectares (about 346,000 acres) under coca leaf cultivation, similar to the amount registered at the beginning of the 2000s, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). But that was before the United States and Colombia implemented “Plan Colombia” in the 2000s, through which the U.S. invested over $10 billion to tackle, among other things, coca growth.

What’s happening in Colombia?

Colombia is the largest producer of cocaine, the second largest illicit drug consumed in the world, which means what’s happening in Colombia matters to the rest of the world. Cocaine revenues help finance transnational criminal organizations, drug lords and warlords not only in Latin America, but also in Europe, Asia and Africa, according to the book, Africa and the War on Drugs, by Neil Carrier and Gernot Klantschnig. Hence, understanding Colombia is key to cutting the illicit resources of drug trafficking organizations everywhere.

To grasp the international threat posed by the increase in coca production, it’s important to be aware of the current situation in Colombia. The country has become a security kaleidoscope on the national and international levels. In 2016, the Colombian government and the criminal/terrorist group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed peace agreements to begin FARC’s demilitarization. The agreement ended a 50-year conflict in which the FARC — which originally fought for farmers’ land rights but morphed into an organized crime and terror group that produced and trafficked cocaine — ceased all armed and illicit activities and transformed into a political party. However, the conflict has not ended, or even decreased, the production of coca leaf, raising the question of who controls the coca production once controlled by the FARC.

Since the U.S. supported Colombia’s effort against the FARC, it is likely that the U.S. will reduce its support in terms of security and funding, impacting the overall fight against coca production. If Colombia is viewed as an organic system in which all the parts interact to ensure the survival of the state and its rule of law, U.S. assistance — in its different forms — has served as a booster shot that helped the state organism fight off the sickness caused by security threats.

This should matter to the international community because, according to the UNODC, the top five per capita cocaine consuming countries are Albania, the U.S., the United Kingdom, Spain and Australia, three of which are in Europe. Considering that coca can only be cultivated in the Andean region (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela), what happens in the production zone will affect the dynamics of the cocaine supply chain in the rest of the world. The economic principles of supply and demand tell us that an unprecedented increase in production could be in response to an unknown increase in demand. However, it could also imply better production methods or a decline in the Colombian government’s capacity to restrain coca cultivation. In any case, it could create a surplus of the drug that could drop its retail price, making it more affordable to more people and creating an opportunity for drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) to increase consumption of the drug worldwide.

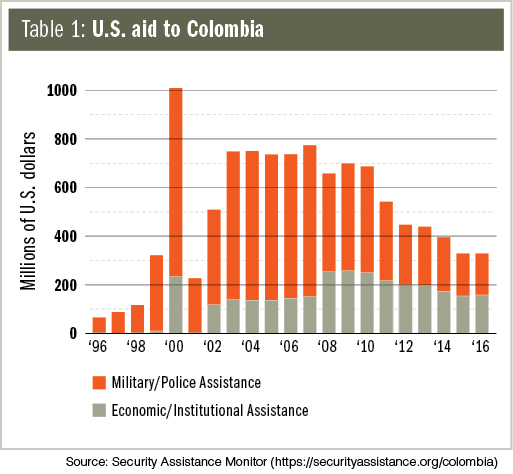

Growing more coca

During the last two decades of the 20th century, Colombia was immersed in drug trafficking and narcoterrorism in which the Medellin cartel, the major DTO at the time, engaged in a violent fight against the authorities. By 1994, U.S. security agencies, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration, had helped the Colombian government take down the Medellin and Cali cartels. In parallel, the government was trying without success to negotiate a peace agreement with the FARC, which in turn filled the power vacuum left in the cocaine trade after the cartels were defeated. The drug problem reached the point that, in 2000, the U.S. and Colombia initiated Plan Colombia. From 2000 to 2016, the U.S. gave more than $10 billion of foreign assistance to support Plan Colombia and later programs, according to a November 2017 report by June Beittel and Liana Rosen for the U.S. Congressional Research Service. However, assistance decreased after 2012.

Under these changing circumstances, coca production has increased, and the Colombian government has not been able to efficiently address the problem on its own. As can be seen in the UNODC World Drug Report 2017, the area under coca cultivation increased from 69,000 to 96,000 hectares from 2014 to 2015, and to 146,000 hectares in 2016, an increase of more than 100 percent in less than three years. However, according to the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, cultivation grew from 80,500 to 188,000 hectares between 2013 and 2016. While the estimates between agencies differ, the abrupt increase in coca cultivation is evident.

At the same time, as shown in Table 1, there is a correlation between the decrease of U.S. aid and the increase in coca production; aid was reduced to historic levels of less than $400 million per year in 2014. It is also possible that the increase is linked to ending aerial spraying of coca crops; however, this is yet to be assessed because the program was halted in 2016. U.S. Undersecretary of Political Affairs Thomas Shannon announced a new strategy in March 2018, following high-level bilateral meetings. The U.S. and Colombia will work together to reduce coca cultivation 50 percent by 2023.

Perhaps the Colombian state’s institutional capacities without U.S. support are still not sufficient to counter coca growth. More important, in 2017 Colombia experienced a historic moment when the FARC peace accords were signed, and negotiations with the National Liberation Army (ELN) — Colombia’s second-largest guerrilla group — were scheduled, generating a criminal power vacuum in the region. That the increase in coca production occurred at the same time as the FARC peace agreements raises the question of who is in charge of coca production, a question that needs to be answered. In one possible scenario described in the Atlantic Council report, “Latin America and the Caribbean 2030: Future Scenarios,” Gina Montiel of the Inter-American Development Bank projects that in 2030, Colombia will better be able to fight illegality, having improved its democratic institutions and strengthened its security apparatus and rule of law. However, today’s increasing coca production indicates that the fight against illegality may be more complicated than it seems.

Why does Colombia matter to the international community and the top cocaine-using countries? There has been an alarming increase in coca production, which presumably means more cocaine on the market. Additionally, it is seemingly unclear who is controlling the increase in production or where the additional cocaine is destined. So far, neither the U.S. nor Europe has registered a sufficient increase in demand to account for the apparent surge in supply.

Moreover, in these uncertain circumstances, the security communities in Colombia and elsewhere may come to different understandings about who is filling the power vacuum left by the FARC’s exit and how that impacts the international cocaine market. In the next few years, either the ELN will take control of the FARC’s abandoned coca production and cocaine trafficking business, or a new player — national or international — will step in. Regardless, the increase in coca cultivation should be of concern everywhere. If demand for cocaine is growing, it will mean more revenue for narcotics trafficking networks, which means more influence and power for criminal organizations.

Transnational organized crime is a complex network of multidimensional contacts and alliances. As this criminal world evolves, criminal organizations find new ways to cooperate with each other. Therefore, a change in one place can precipitate multiple changes that provoke the creation of new alliances. Moreover, alliances between transnational organized crime groups are created much faster than international cooperation agreements can be established between governments, putting law enforcement at a disadvantage. Therefore, countries with a cocaine problem need to understand what is happening in coca-producing countries and with trafficking networks to assess the drug’s supply and street market value.

The land of coca

Joint U.S.-Colombian efforts have reduced criminal instability; however, Colombia may have become dependent on U.S. security support. Perhaps reduced levels of U.S. support are contributing to the increase in coca production. If Colombia’s security apparatus is vulnerable, the drawdown of U.S. support could provoke instability and criminal violence similar to what is happening in some Central American countries. Weaker Colombian security structures would make it easier for cocaine to be produced and trafficked to the rest of the world.

The regional geopolitical scenario is of even greater concern for Colombia’s security. Venezuela’s social unrest and economic crisis, and Brazil’s counternarcotic efforts each generates its own spillover effects that necessitate Colombia to take preventive measures. The rate of inflation has been increasing exponentially in Venezuela since 2010. The unstable economic situation could provide opportunities for new criminal groups and increased illicit activity and spark irregular migration toward more stable countries. Any new criminal organizations are likely to be oriented toward highly profitable cocaine, which can be trafficked across different points along the more than 2,000-kilometer shared border.

Brazil, Venezuela and Colombia share a tri-national border in a region plagued by the trafficking of illicit substances, which are often moved through Brazil to be shipped across the Atlantic. According to the World Drug Report 2017, 58 percent of the cocaine trafficked to Africa and 35 percent trafficked to Asia exits South America via Brazil. Additionally, Brazil has emerged as a key consumer of cocaine, Paula Miraglia wrote in a 2016 report for Brookings. Apart from trafficking cocaine out of the Andean region, this incentivizes criminal organizations to spread their tentacles to supply the growing local market, making them even more difficult to combat. When Brazilian authorities cooperate with their African and Asian counterparts to tackle international trafficking, the increasingly sophisticated Brazilian networks make it ever more difficult to stop the drugs from leaving the departure ports.

Conclusion

In 2016, there were an estimated 213,000 hectares (526,000 acres) under coca cultivation in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, with 68 percent of that in Colombia. According to the UNODC, that much coca carries the potential to produce 866 metric tons of cocaine. As the world’s largest producer of coca and cocaine, Colombia’s dynamics of security and drug production should concern every country fighting cocaine trafficking and use at home.

The cocaine trade is directly or indirectly connected to many of the world’s transnational criminal organizations. Cocaine trafficking to Europe has contributed to the empowerment of warlords and criminals in some West African countries, according to Carrier and Klantschnig. It is a source of substantial revenue for dangerous mafias such as Italy’s ’Ndrangheta which, as reported in the newspaper il Quotidiano del Sud, plays a central role in trafficking and distributing cocaine in Europe. In Albania, which suffers from the highest per capita rate of cocaine users in the world, local mafia groups feed the problem while also playing a major role in the U.K. market, says the United Kingdom National Crime Agency.

Cocaine trafficking is an illicit business that funds terrorists, warlords and some of the most vicious mafias in Europe, Asia and around the world. However, unlike cannabis, methamphetamines or even heroin, cocaine is produced from a plant that can be grown only in the Andean region of South America. What happens in this region, and especially in Colombia, the most prolific cocaine producer, should concern everyone.

Comments are closed.