Lessons for future crises

By Dr. Bernhard Wigger, head of the core planning team for the Swiss Security Network Exercises at the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport

Photos by Swiss Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport

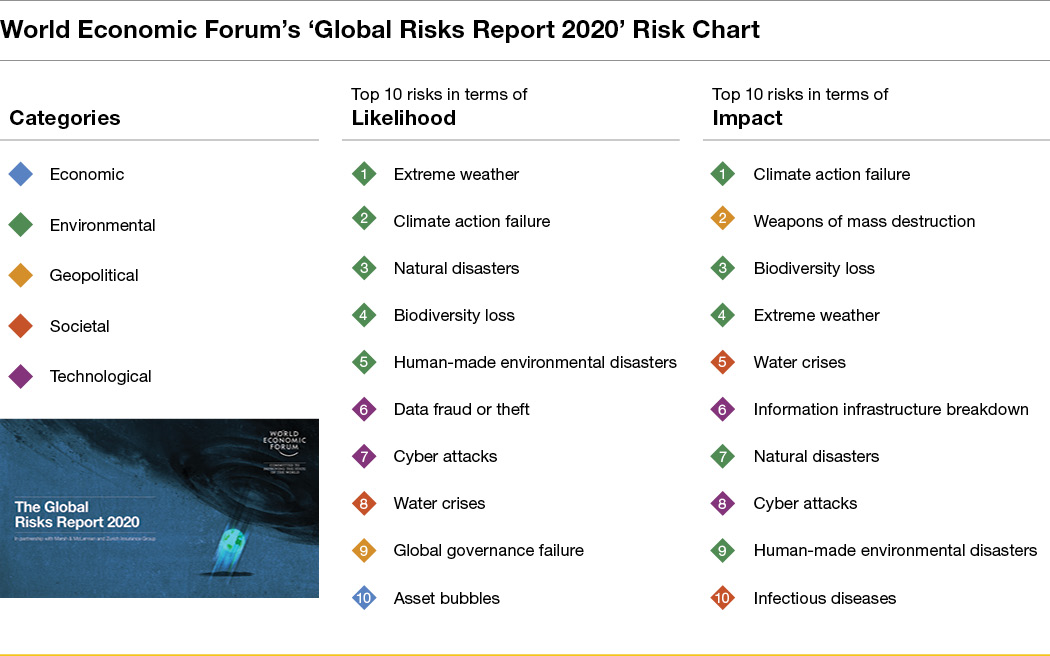

Despite warnings of the devastating effects on societies and globalized economies, a pandemic was not at the top of the list of risks in January 2020 when the World Economic Forum presented the 15th ‟Global Risks Report.” The survey focused predominantly on environmental risks. An infectious disease outbreak was considered unlikely, and the impact of epidemics/pandemics ranked last on a risk chart. Not surprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic took national and international crisis management agencies by surprise, shattered the self-confidence of societies, and challenged international cooperation and multilateral organizations. The world was taken completely unaware and the results were devastating. How could this have happened? And what can we learn to prepare for similar events?

The coronavirus pandemic was still raging as this was written and a comprehensive evaluation of the handling of the crisis can be made after the world emerges on the other side, with the necessary objective distance. However, experiences to date and lessons already identified allow us to begin to consider how states and their governments could improve crisis management systems. The aim is to consolidate best practices to better prepare for future crises.

The lessons learned from COVID-19 can serve as an impetus to overhaul crisis management structures and equip them to handle the entire spectrum of crises. The challenge is to prepare for every type of disruptive emergency. A preliminary analysis suggests the following conclusions for the operational, strategic and political levels of crisis management:

The operational level bears the brunt of the crisis and can build on its daily routine in handling events. However, changes must be made to the way data is collected and exchanged and to the way an integrated overview of the system is obtained.

At the strategic level, the greatest potential for improved crisis management lies in developing strategic courses of action for political decision-makers. However, to work effectively, staff must be trained in scenario-based contingency planning.

At the political level, at least in liberal democracies, politicians must win over the public by communicating and following a clear problem-solving strategy.

Dealing with a disruptive crisis goes beyond simply coping with technical issues. COVID-19 taught us that containing the epidemic is not enough. The overall situation must be mastered as well. Leaders must be mentally prepared for this task and have the leadership skills to work within national and multinational networks. The views expressed here relate primarily to the way the COVID-19 crisis has been dealt with in Switzerland. The conclusions are based on this author’s experiences working as a political advisor to the Swiss Armed Forces, as head of the Swiss Security Network office and as project manager for the 2019 national Security Network Exercise.

The Limits of Specific Blueprints for Crisis Handling

In 2013, the Swiss government stipulated that a pandemic should be part of the first Security Network Exercise in 2014, which was designed to test the overall national security system. The main exercise focused on a blackout and subsequent electricity shortages. The outbreak of a pandemic further complicated the crisis management. The pandemic part of the exercise concentrated on an overhaul of the national contingency planning for pandemics. This revision work was successfully concluded in 2018 with the publication of an updated Swiss Influenza Pandemic Plan.

The COVID-19 crisis has clearly demonstrated the limits of contingency planning. Contingency plans are basic documents that give direction and contain recommendations. A political decision must be made on whether to adopt the recommendations and how to implement them. Moreover, crisis handling is much more than implementing plans — it is well known that plans seldom survive contact with the enemy. Plans can be of assistance, mainly at an operational level. They cannot determine the overall management of a national crisis because they focus too specifically on one sector of the security system. Nor can they guarantee the smooth functioning of the main decision-making processes. This is the main challenge: preparing a whole system for a spectrum of major crises — what are termed “disruptive crises” in this article.

A Wake-Up Call for Future Crises

The term ‟disruption” sums up the effects of the COVID-19 crisis very well. It invokes damage, destruction and interruption. In logistics, when production and supply chains fail, we talk of disruption. Above all, there is a fear of disruption in connection with cyber risks. Disruptive effects are a predicted consequence of a pandemic. In October 2019, the comprehensive ‟Global Health Security Index” reached the alarming conclusion that no country was fully prepared to handle an epidemic or pandemic. The survey, covering 195 countries, found severe weaknesses in these countries’ abilities to prevent, detect and respond to major disease outbreaks. The current situation has confirmed this prognosis.

Disruptive events can be understood by the responses to them. The 9/11 terrorist attack brought fundamental changes in security policy; the 2008 financial crisis had a major impact on national economies; and the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima led to changes in energy policy. COVID-19 can also be regarded as a disruptive event because of its vast social, economic and political effects. Although viral disease is a familiar phenomenon in the history of humankind, it is unlikely that COVID-19 would have caused much of a stir in earlier times; for example, its mortality rate is low when compared to the 1918 influenza pandemic. The devastating disruptive power of the current pandemic is due to the interconnectedness of today’s societies and economies. They are vulnerable to interruptions and sensitive to media hype and social network storms.

This predisposition in our societies leads us to expect other forms of disruptive crises, not just pandemics. These include natural or civil disasters and cyber or terrorist attacks. In the case of cyber risks, digital networking contributes to increasing vulnerability. In the case of terrorist threats, two developments accentuate the disruptive potential:

First, the potential for developing the strategic planning and sophistication of attacks, particularly on soft targets in an open society, gives cause for concern.

Second, there is a fear that sooner or later weapons of mass destruction will be used, with devastating consequences.

The lessons learned from COVID-19 will help security specialists anticipate and manage disruptive crises.

Strategic Crisis Management as a Focal Point

Strategic Crisis Management as a Focal Point

The response to most crises, whether natural phenomena, terrorist attacks or cyber incidents, begins at the tactical level and escalates — depending on the threat to public safety and security — to an operational level. A typical example is a terrorist incident. Although such attacks are escalated immediately in the media at national and even international levels because of the high interest in terrorist threats, as far as crisis management is concerned they can normally be dealt with operationally by the specialists and their teams. Therefore, they are not a serious threat to national security and do not cause nationwide disruption.

In contrast, COVID-19, as a disruptive crisis, marks a turning point in crisis management. It has demonstrated that dealing with problems at an operational level — in this case through the work of epidemiologists — is no longer enough. The challenges posed by secondary problems and chain reactions require a strategy that addresses the overall problem and not just the public health situation. This is the only way to bring the crisis under control; focusing on one aspect is not enough.

Strategic action on the supply of protective equipment, virus testing and tracing has remained inadequate under the current approach because of the vacuum between operational crisis management teams and political decision-makers. Because of this, the key question is how strategic crisis management can be improved. How can strategic planning teams (most of them ad-hoc bodies because of the low probability that disruptive crises will occur) be prepared for an emergency?

The importance of a functioning system of strategic crisis management becomes most clear at a political or executive level. This is where decisive leadership is required more than anywhere else. The public is rightly entitled to expect their political leaders to do everything to bring a crisis under control. Especially in the case of disruptive crises, which hit society so hard, people expect their leaders to reduce or at least manage the disruption.

Probably the most important lesson from the COVID-19 crisis is that the everyday administrative structures for the management of this type of crisis are insufficient. At a strategic level, teams that work specifically on devising strategic options for crisis management are required. Political leaders must then distill these strategic options to form a strategy, implement it and inform the public regularly of what progress has been made. Crisis managers at all levels, including political leaders, must be prepared for this task. To this end, scenario-based training sequences must be used to ensure mental readiness for disruptive crises. Large-scale simulation exercises can prepare structures and processes for a real crisis.

War-gaming for Mental Preparedness

Preparation for future disruptive crises begins with an analytical evaluation of the scenarios to heighten anticipation. The scenarios developed must cover exceptional situations, ranging from natural disasters such as earthquakes, through civil disasters such as power outages and public health crises such as pandemics, to threat scenarios where, as already mentioned, the current focus is on strategic cyber attacks and protracted periods under the threat of major terrorist attacks.

War-gaming is a method in which a group works its way through a variety of scenarios. In a threat scenario, participants discuss different modes of attack by their adversary and the best courses of action to counter them. When it comes to disasters, the courses of action relate to systematic consequence management.

At operational, strategic and political levels, formats must be defined that allow for a discussion of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis, using the war-gaming method. In a pandemic, operational teams such as health care specialists or, more generally, civil protection teams function routinely through daily incident management. By analyzing exceptional situations and disruptive scenarios, those teams can anticipate and prepare for the special demands of such situations. COVID-19 has revealed deficiencies primarily in the ability to see the bigger picture and in the electronic exchange of data. Regarding the bigger picture, the challenge lies in putting together an integrated strategic situation report that accounts for numerous sectors, such as health, the economy, society, international relations and the armed forces. This task must be assigned to a specific lead agency, the choice of which depends on the nature of the crisis.

Regarding data exchange, the aim is to automate so that all parties have a consolidated and reliable database. In addition, complex prognoses must be broken down into simple and comprehensible models that can be intuitively understood and used by crisis managers from outside the field. Switzerland emerged from the Security Network Exercise in 2019 with very positive war-gaming experiences. This sequence of the exercise involved about 50 representatives from the 12 main police, civil protection and Armed Forces units in combating terrorism. They worked their way through 19 scenarios, discussing potential responses. These analyses, based on the war-gaming method, can conceivably be used for other crisis scenarios.

Tabletop analyses must involve not only people working at an operational level, but also those engaged at the strategic and even political levels. Here, national crisis plans and crisis structures can be discussed in senior executive seminars. Best practices can be identified that serve to prepare participants for the next crisis. In addition, participants in seminars on dealing with disruptive scenarios can bring back proposals for optimizing national crisis management.

Exercises for Organizational Preparedness

Large-scale national exercises used to take place regularly in line with general national defense policy to test the capabilities of the overall security system. With the end of the Cold War, this training culture went into decline. In Switzerland, the government announced in its 2010 security policy report that it was again planning to hold complex, large-scale exercises regularly. In 2014, the first such security network exercise in 22 years was held. The final report recommended having such an exercise every four to five years, and the Swiss Confederation and cantons agreed.

The authorities and decision-makers in the Security Network should regularly simulate a serious emergency to identify weaknesses in the precautions taken and in the structures and processes, and to improve on them. Anyone who does not prepare and practice for crises will make avoidable errors in real emergencies and will cause unnecessary damage, which may include the loss of human life.

Undoubtedly, the largest challenges are coordinating the numerous actors at all levels of the state and in all sectors concerned, and communicating with the public and the media. This interaction with many different partners in an exceptional situation is unusual and must therefore be practiced regularly. Last, the central government and the cantonal governments must be included to ensure that the knowledge gained does not remain at the operational level only.

In a comprehensive security network, the armed forces fulfill the vital role of a strategic reserve. They can make both quantitative and qualitative contributions across the entire spectrum of crises. This flexibility to provide services as part of the National Security Network must therefore be considered an important factor in the development of the armed forces. By providing these essential services, the Armed Forces are recognized as a partner in the network. The Swiss Armed Forces have clearly shown during the COVID-19 crisis that they can provide substantial manpower in little time. In March 2020, when the Swiss Armed Forces ordered with a single text message the mobilization of about 5,000 members, 80% of those called up responded within 15 minutes to say they were on their way. In the following weeks, these Armed Forces members supported civilian authorities in providing medical services, embassy protection and border controls. The government had decided that the Armed Forces could call up a maximum of 8,000 of its members to meet civilian authorities’ needs.

Last, it is important to publicize these exercises and to raise public awareness of how we can respond to crises. If the public can be made aware of potential problems by means of a major exercise, it will understand the difficulties better in the event of a real crisis and accept instructions from the authorities. The inclusion of the public and its readiness to help solve the problem are important factors in successful crisis management in a free society. The current pandemic has shown us this with clarity. In the future, information on security policy must be provided not simply to a limited group of specialists but to the public in general.

Conclusions

A clear-sighted security policy involves a systematic assessment of the dangers, risks and threats that are relevant today and in the foreseeable future. These include natural and civil disasters, interruptions in energy, commodity and food supplies, economic crises, epidemics, pandemics, mass migration, political and social crises, and threats to internal security from extremism and terrorism that endanger the population and critical national infrastructure. To prevent and overcome such disruptive crises, all relevant authorities and instruments, such as security policy, intelligence, foreign policy, economic policy, the armed forces, police, civil protection, customs and border protection, health and civil aviation authorities, must be coordinated and synchronized. The representatives of all the departments, institutions and organizations concerned must meet to make a comprehensive assessment of the situation and contribute to joint planning and decision-making. To prepare these mid- to high-level officials for this task, suitable training methods are required:

Scenario-driven, tabletop formats such as conferences, seminars and workshops allow the physiognomy of different crises to be analyzed so that best practices can be identified and national approaches shared and disseminated. Scenarios are simulations of real-life events that help leaders develop the imagination required to anticipate and identify threats.

Functional exercises are the appropriate maneuvers for the 21st century, not in the context of a total-defense concept, but in terms of comprehensive security. They serve as regular stress tests for national crisis management systems, including armed forces’ support for civil authorities, thus preparing them to handle the next series of disruptive crises, which are sure to arise.

Comments are closed.