It takes partnerships and planning

By Danielle Santos, program manager. National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, United States Department of Commerce

As the world becomes ever more connected through technology, the need for a workforce that can protect those technologies becomes increasingly important. However, studies show that the supply of cyber security talent is not meeting demand. The cyber security workforce shortfall is well documented. The “(ISC)2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2019” estimates that the global workforce needs to grow by 145% to meet the demand of businesses today. In the United States alone, CyberSeek.org estimates there are currently over 500,000 unfilled cyber security jobs.

Further, the time it takes to hire and train employees causes lengthy setbacks for organizations. ISACA’s “State of Cybersecurity 2020” report indicates that for nearly 30% of survey respondents, filling a cyber security position with a qualified candidate takes more than six months. Another 30% report that filling positions takes three months. Additionally, 70% of respondents generally do not believe their applicants are well qualified for the job. A collaborative approach to producing a workforce skilled in cyber security can help minimize these critical issues.

Public-private partnerships

The National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE), led by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), an agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce, represents a public-private partnership of academia, industry and government, whose mission is to promote and energize a robust and integrated cyber security education and workforce ecosystem. That is why NICE proudly embraces ideals such as facilitating collaboration, fostering communication and sharing resources.

NICE has been operating under a strategic plan developed in 2016. The Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014 reaffirms the role of NICE, and Title IV of the act directed the NIST, as the lead agency for NICE, to develop and implement a new strategic plan every five years to guide federal programs and activities in support of the national cyber security education program. The act further directs NIST, “in consultation with appropriate Federal agencies, industry, educational institutions, National Laboratories, the Networking and Information Technology Research and Development program, and other organizations, [to] continue to coordinate a national cybersecurity … education program” and to develop: “supporting formal cybersecurity education programs at all education levels to prepare and improve a skilled cybersecurity and computer science workforce for the private sector and Federal, State, local, and tribal government; and … promoting initiatives to evaluate and forecast future cybersecurity workforce needs of the Federal government and develop strategies for recruitment, training, and retention.”

The NICE Strategic Plan is the result of engagement and deliberation among NICE partners in government, academia and industry. The plan outlines a vision, mission, values, goals and objectives. NICE partners will continue to develop appropriate implementation strategies, metrics and plans to announce a new five-year strategic plan in November 2020.

NICE Vision

The NICE vision is for a digital economy that is enabled by a knowledgeable and skilled cyber security workforce. The increasing reliance of the public and private sectors on a resilient cyberspace for the delivery of online services to citizens and consumers demands a holistic effort that includes the need for people with the necessary knowledge, skills and abilities to perform tasks that lead to increased security of data and computer networks.

NICE Mission

The mission of NICE is to energize and promote a robust network and an ecosystem of cybersecurity education, training and workforce development. Although the NICE acronym emphasizes education, training provides an increasingly important educational opportunity, whether provided by a commercial entity or employer. Certifications, especially when accompanied by hands-on learning and performance-based assessments, are credentials that can be used to validate knowledge, skills and abilities. NICE is also focused on developing a skilled cyber security workforce, so making sure that educational providers and employers are aligned with the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (or NICE Framework) is a priority.

NICE Values

Perhaps the most important aspect of the strategic plan development was the socialization process that led to the creation of a shared set of ideals. Collaboration and Communication are at the center of how NICE seeks to create a sense of community that will encourage stakeholders to Share Resources. We serve diverse communities and rely on thought leadership from across economic sectors, so it is important that we Model Inclusion in our programs and activities. We also want to be known for our ability to Pursue Action and get things done so it is important that we Challenge Assumptions, Seek Evidence and Measure Results. The challenges are immense, and the status quo is insufficient so we must be prepared to Embrace Change and look for ways that we can Stimulate Innovation. Together, as a community, we can collectively make progress to close the cyber security skills gap and enhance our economic and national security.

The strategic plan sets forth a broad set of goals and objectives designed to inform actions and determine priorities for the next few years.

Recognizing the widening gap between the growing demand for skilled cyber security workers and the available supply, the first goal is to Accelerate Learning and Skills Development. We must inspire a sense of urgency in both the public and private sectors to address the shortage of skilled cyber security workers. This goal represents perhaps the greatest challenge and most critical need to identify creative and effective ways to close the skills gap. These objectives challenge us to experiment with new approaches, such as the use of apprenticeships and cooperative education programs, to move students into the workforce more rapidly. The objectives also invite us to find ways to move displaced workers or underemployed individuals into cyber security careers.

The second goal, recognizing the unique contributions of educational providers and the backgrounds of diverse learners, compels us to Nurture a Diverse Learning Community. The aim is to strengthen education and training across the ecosystem to emphasize learning, measure outcomes and diversify the cyber security workforce. There have been significant investments in the development of education programs, co-curricular experiences, training and certifications; however, we must work to continuously improve to make sure that those programs are having the intended impact on diversity. The Centers for Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity, led by the National Security Agency and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the Advanced Technological Education Centers in Cybersecurity funded by the National Science Foundation represent significant momentum to build capacity and increase participation by institutions of higher education. It is widely recognized that to sustain the pipeline needed for a robust cyber security workforce we must introduce students to career opportunities as early as possible and ensure that their academic preparation in secondary schools propels them into higher education. The underrepresentation of women and minorities and the underutilization of veterans in the cyber security workforce is a well-documented concern, and we must develop concrete actions that reverse those trends.

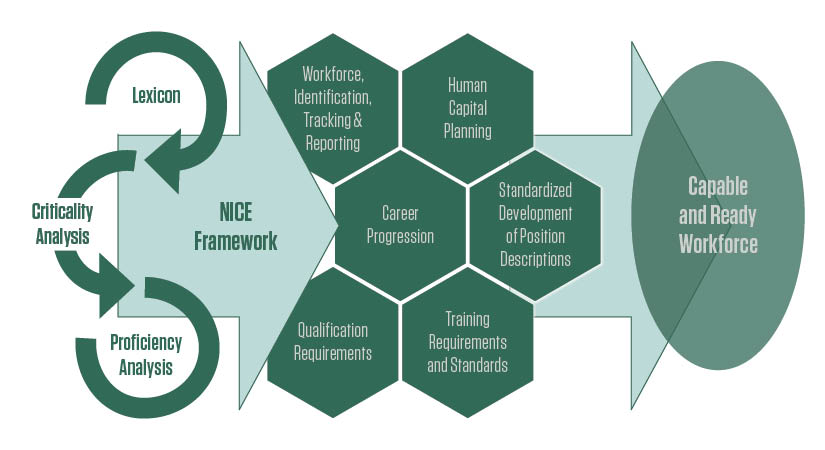

Finally, the opportunities afforded by cyber security employment will provide an economic development boom to communities, but public sector and private sector employers need guidance to help them navigate this ever-changing career field. That is why our third goal is to Guide Career Development and Workforce Planning. Human resource professionals, hiring managers, and cyber security professionals require support to address market demands and enhance recruitment, hiring, development and retention of cyber security talent. CyberSeek.org, funded via financial assistance from NIST, the nonprofit CompTIA and Burning Glass International Inc., is part of the overall objective to identify and analyze data sources that support projecting present and future demand and supply of qualified cyber security workers. Additionally, the NICE Challenge Project (https://www.nice-challenge.com), developed by California State University, San Bernardino, is creating virtual challenges based on the NICE Framework tasks. The Cybersecurity Workforce Development Toolkit developed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is an example of a tool that will assist human resource professionals and hiring managers.

America’s Cybersecurity Workforce Executive Order, announced on May 2, 2019, called for a “consultative process that includes Federal, State, territorial, local, and tribal governments, academia, private-sector stakeholders, and other relevant partners to assess and make recommendations to address national cybersecurity workforce needs and to ensure greater mobility in the American cybersecurity workforce.” We did not have to look very far to find existing mechanisms, including the NICE Working Group.

The NICE Working Group, established in 2015, provides a mechanism by which public and private sector participants can develop concepts, design strategies, and pursue actions that advance cyber security education, training and workforce development. The working group is led by three co-chairs, each representing academia, industry and government. The NICE Working Group is composed of six subworking groups focused on topics or audiences interested in primary and secondary school cyber security education, collegiate cyber security education, cyber security competitions, cyber security training and industry-recognized certifications, workforce management, and cyber security apprenticeships. Each of the subgroups, as well as the full working group, are open to the public.

The working group and subgroups continue to actively identify projects and produce products (one-pagers, white papers, tools, presentations, etc.) that are directly responsive to the goals and objectives of the NICE strategic plan. The working group is actively consulted for input. For example, as NICE looks to have an updated strategic plan this year, each subgroup has focused meetings to deliberate on the needs and to brainstorm themes, goals and objectives for the future strategic plan. The working group and each subgroup were also actively engaged during the summer of 2017 when NICE organized a process to respond to the requirements of the Executive Order on Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, to include an assessment of “the scope and sufficiency of efforts to educate and train the American cybersecurity workforce of the future, including cybersecurity-related education curricula, training, and apprenticeship programs, from primary through higher education” and “provide a report to the President with findings and recommendations regarding how to support the growth and sustainment of the Nation’s cybersecurity workforce in both the public and private sectors.” The consultative process used at that time resulted in the “Report to the President on Supporting the Growth and Sustainment of the Nation’s Cybersecurity Workforce: Building the Foundation for a More Secure American Future” (Workforce Report).

Other ways that NICE seeks to consult with academia and industry include:

Other ways that NICE seeks to consult with academia and industry include:

- Requests for information (RFI) that seek input on cyber security education and workforce topics, such as the RFI issued in response to Executive Order 13800 that requested “information on the scope and sufficiency of efforts to educate and train the Nation’s cybersecurity workforce and recommendations for ways to support and improve the workforce in both the public and private sectors.”

- Public comment periods are routinely used to encourage review and feedback of draft NIST publications, including NIST “Special Publication 800-181” that established the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework.

- Engagement with the Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board of NIST, established in accordance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) to advise NIST on information security and privacy issues.

- Insights from the American Workforce Policy Advisory Board, another FACA group, that provides advice and recommendations to an interagency council led by the U.S. Department of Commerce pursuant to the executive order, “Establishing the President’s National Council for the American Worker.”

- Other public forums or advisory boards established for other federal government departments and agencies.

- Participation in events supported by grants from NIST such as the annual NICE Conference and Expo, the NICE K12 Cybersecurity Education Conference, and the Center for Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity Symposium held each year immediately following the annual NICE Conference and Expo.

- Invitations as speakers or guests at other academic and industry meetings or events where NICE community members can listen and learn about emerging issues, opportunities, and programs of public and private sector organizations.

The public is invited to join and participate in the NICE Working Group by attending the NICE Conference or one of the other NICE-supported events, including cyber security education-related and workforce-related discussions at meetings or events.

NICE also engages with government organizations. The NICE Interagency Coordinating Council convenes federal government partners of NICE for consultation, communication and coordination of policy initiatives and strategic directions related to cyber security education, training and workforce development. This group meets regularly to provide an opportunity for the NICE Program Office to communicate program updates with partners in the federal government and to learn about other federal government activities in support of NICE. The group also actively identifies and discusses policy issues and provides input into the strategic direction for NICE.

A Common Thread

The NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework was designed to create a common language for categorizing and describing cyber security work and offer a tool for baselining capabilities, identifying skill gaps and ensuring a robust cyber security talent pipeline. The first version of the NICE Framework was published in 2012 and has become a nationally focused standard for cyber security employers, practitioners, educators, training providers and learners across public, private and academic sectors. It is also used internationally as a reference resource. As more organizations align their workforce development efforts to a common taxonomy, the result will be a more standardized cyber security workforce that can more effectively secure our networks and systems.

The most recent version of the NICE Framework was published in August 2017 as NIST “Special Publication, 800-181.” This version expanded the original lexicon to include a refined taxonomy of cyber security work categories, specialty areas, and now roles. NIST “Special Publication 800-181” was also the first version to include details on the “Collect and Operate” and “Analyze” work categories and related knowledge, skills, abilities and tasks. Earlier versions redacted information on these categories due to their highly specialized and sensitive nature. This offered learners deeper insights into the nature of this work and enabled educators and training providers to prepare workers in these areas.

The NICE Framework will continue to evolve with the needs of the communities that it can serve. NICE is leading an effort to dynamically maintain the NICE Framework’s relevancy, applicability and utility while improving its ongoing alignment with related standards, guidelines and other frameworks. Keeping the NICE Framework relevant is vital to prepare our nation’s workforce for increasingly complex cyber security challenges. As such, we began a regular update cycle and announced plans in November 2019 to publish a revision of NIST “Special Publication 800-181.” Prior to publication, a draft was produced for public comment. NICE Framework updates will happen in cooperation with the private sector and other government agencies via transparent, open and collaborative processes.

The NICE Framework will continue to evolve with the needs of the communities that it can serve. NICE is leading an effort to dynamically maintain the NICE Framework’s relevancy, applicability and utility while improving its ongoing alignment with related standards, guidelines and other frameworks. Keeping the NICE Framework relevant is vital to prepare our nation’s workforce for increasingly complex cyber security challenges. As such, we began a regular update cycle and announced plans in November 2019 to publish a revision of NIST “Special Publication 800-181.” Prior to publication, a draft was produced for public comment. NICE Framework updates will happen in cooperation with the private sector and other government agencies via transparent, open and collaborative processes.

Changes to the NICE Framework will be framed by lessons learned from those who use and apply it. Workforce planners, educators, training providers, employers and learners may bring forth needs for additional NICE Framework components or informative references. When we actively engage the private and public sectors on standards like the NICE Framework, we rely on and use experts from around the country — and around the globe — to improve the quality, relevance, and likely use of the end product. We learn about needed improvements by getting feedback from those who have consulted, implemented, applied or mapped to the NICE Framework. Some of these cases include performing workforce audits, developing position descriptions, creating learning outcomes, validating knowledge, skills, and abilities, and creating career pathways for learners and job seekers.

Stronger Together

In September 2016, the NICE Program Office awarded funding for five pilot programs for Regional Alliances and Multistakeholder Partnerships to Stimulate (RAMPS) Cybersecurity Education and Workforce Development. These programs aimed to bring together employers who have cyber security skill shortages with educators to focus on developing a skilled workforce to meet industry needs within local or regional economies. One of the requirements for the program was that each participant had to identify partnerships with at least one of the following: a K-12 school or local education agency, an institution of higher education or college/university system, and a local employer.

Creating these RAMPS programs showed, through metrics, that regional alliances and partnerships can have a positive impact on strengthening the cyber security workforce. Groups saw increases in student participation in courses, increases in career awareness, and more cyber security internships being secured. This evidence shows that creating collaborative environments can significantly change the cyber security workforce ecosystem. As Helen Keller put it: “Alone we can do so little, but together we can do so much.”

Further Reading

The documents listed below are, by no means, a comprehensive list. However, they do provide further context on many of the programs, approaches and materials described in this article.

- NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (https://nist.gov/nice/framework)

- A Roadmap for Successful Regional Alliances and Multistakeholder Partnerships to Build the Cybersecurity Workforce (https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8287)

- Report on the International Workshop on Cybersecurity Education and Workforce Development Capacity Building (https://www.nist.gov/document/nice-international-workshop-report-2019)

- NICE Strategic Plan (https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/nice/about/strategic-plan)

- Supporting the Growth and Sustainment of the Nation’s Cybersecurity Workforce (https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/nice/resources/executive-order-13800/report)

Comments are closed.