Seeking answers to evolving dilemmas

By Demetrios G. Papademetriou, president, Migration Policy Institute Europe, and Caitlin Katsiaficas, research assistant

Three years after the latest European migration crisis erupted with a spike in flows and fatalities in the central Mediterranean Sea, and two years after almost 900,000 migrants and asylum-seekers from the Middle East and beyond arrived in Europe through the eastern Mediterranean, the crisis seems to have subsided. The relative calm, however, is somewhat misleading. While there are no longer seemingly endless numbers of people crossing the Aegean Sea and walking through Greece and the Western Balkans on the way to this century’s apparent promised lands — Germany and Sweden — unacceptably large numbers of people continue to die on the way to Libya and other North African countries and drown in the Mediterranean. And reported conditions under which hundreds of thousands of people are waiting in Libya in the dimming hope that they might be able to cross the central Mediterranean and reach Europe (or, more accurately, be rescued by European-flagged ships) shock even the most hardened observers.

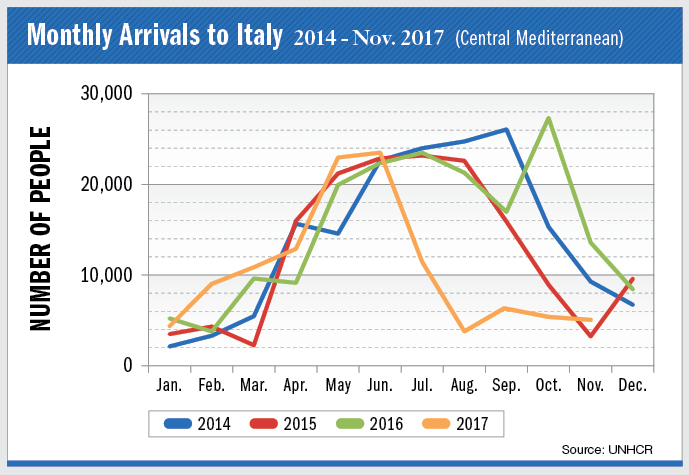

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that 3,038 people had drowned in the Mediterranean as of November 30, 2017, approximately 64 percent of the total 2016 figure. IOM also noted that Italy received an average of 13,959 migrants per month in the first six months of 2017, while the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that the western Mediterranean (Spain) has, once more, become increasingly active, recording 21,300 entries in the first 10 months of 2017 — a 150 percent increase over 2016’s total. Furthermore, sea arrivals to Greece, which had been reduced to a trickle since the end of the first quarter of 2016, started rising in August 2017, with monthly totals about two times larger than the average crossings the previous 16 months. Crossings through Turkey’s land borders with Greece and Bulgaria also have increased.

Overall the migration crisis appears to have morphed into four components: (1) the ongoing challenge of vetting and distributing efficiently and fairly asylum-seekers who entered Europe during the past three years; (2) the simmering political crisis in much of Europe, expressing itself in the growing popularity of populist parties; (3) the humanitarian and political crisis in Greece and, less so, in Italy, the entry points of almost all spontaneous inflows; and (4) over the longer term, a massive integration challenge. And just as the response to the 2015 migration surge was hastily written, in many ways the current situation is unfolding with seemingly few lessons truly learned from the recent past.

Overall the migration crisis appears to have morphed into four components: (1) the ongoing challenge of vetting and distributing efficiently and fairly asylum-seekers who entered Europe during the past three years; (2) the simmering political crisis in much of Europe, expressing itself in the growing popularity of populist parties; (3) the humanitarian and political crisis in Greece and, less so, in Italy, the entry points of almost all spontaneous inflows; and (4) over the longer term, a massive integration challenge. And just as the response to the 2015 migration surge was hastily written, in many ways the current situation is unfolding with seemingly few lessons truly learned from the recent past.

The major exception is Italy’s controversial, but so far quite effective, initiative to work closely with Libya’s internationally recognized (but still not in meaningful control) government, as well as Tunisia and, apparently, several militias operating along Libya’s Mediterranean coast, to prevent migrants from using the Libyan and Tunisian coasts as launching points for crossing the central Mediterranean. Meanwhile, in the handful of European states most affected by the crisis, reception and adjudication systems remain backlogged, while indifference toward those European Union members that bear the brunt of the crisis and recriminations among member states are as strong as ever. More than three years into the crisis, the European Commission remains ill-equipped to address it in a proactive manner, rather than trying to deal, often awkwardly and always with limited success, with its consequences. It remains to be seen whether the apparent commitment of 44 billion euros to African development at the most recent (November 2017) African Union-EU summit in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, may eventually bear some fruit in reducing unwanted migration by addressing its “root causes,” a process that in other settings has taken a generation or longer while increasing illegal emigration pressures in the interim.

Record global displacement

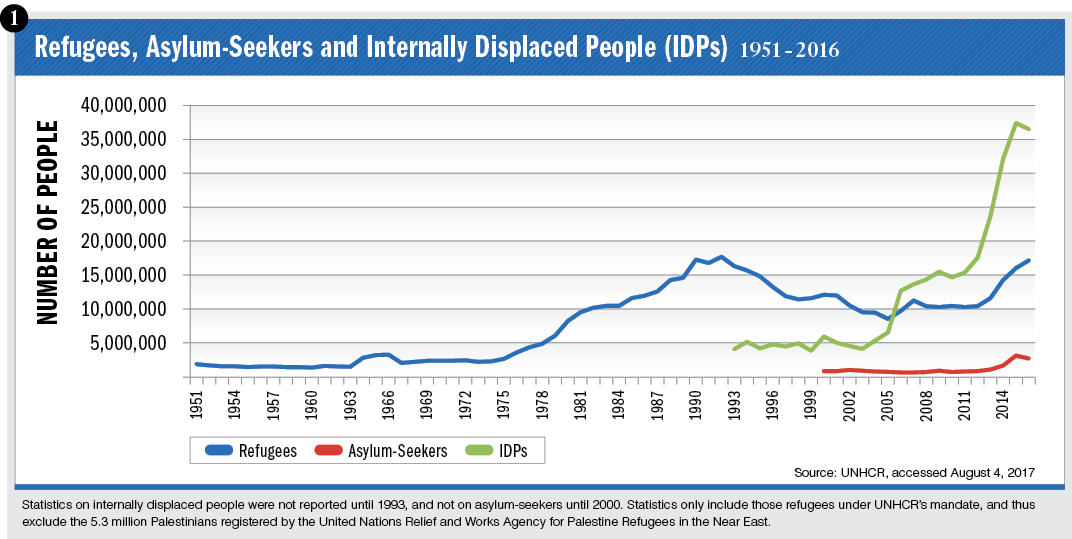

The European migration crisis is but the tip of the iceberg in what is a massive and long-term set of bloody humanitarian crises around the world — born out of seemingly unresolvable conflicts over ethnic and religious differences, territory and resources. The UNHCR identified a record high of 65.6 million forcibly displaced people around the world at the end of 2016, a number that has seen particularly large annual increases since 2011. These figures reflect the highest level of displacement since World War II (See Figure 1).

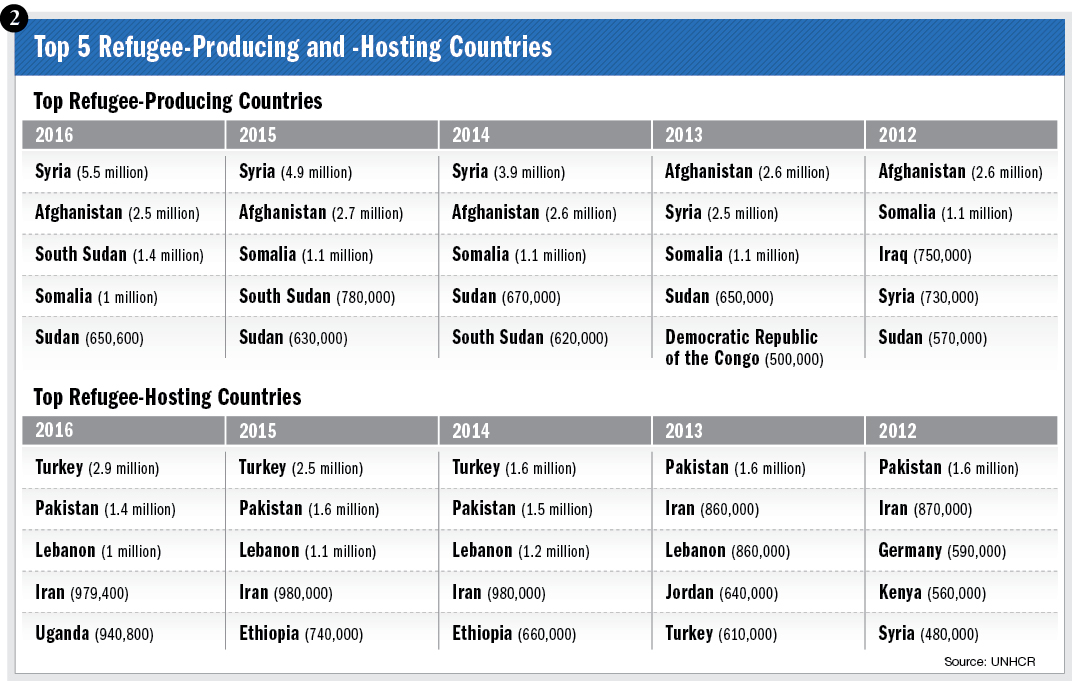

The 2016 data include 40.3 million internally displaced people, 22.5 million refugees and 2.8 million asylum-seekers. But the effects of those crises are distributed unevenly, with only a handful of countries hosting or producing most refugees (See Figure 2). Notably, according to UNHCR’s “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016,” three countries — Afghanistan, South Sudan and Syria — were the source of 55 percent of all refugees, with Syria alone accounting for approximately a quarter of the refugee total, or 5.5 million people. Five countries — Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Sudan and Syria — accounted for 54 percent of all internally displaced people. Conversely, Turkey was host to the largest number of refugees in 2016, at 2.9 million, while Pakistan and Lebanon hosted 1.4 million and 1 million, respectively. Of the refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, 84 percent were hosted by developing countries, a fact that is glossed over in much of the Western media’s reporting about the crisis. And this data does not include three of 2017’s largest refugee flows: the nearly 800,000 Rohingyas who fled from Burma to Bangladesh, and the internally displaced people and refugees produced by the conflicts in Yemen and South Sudan.

Europe unprepared

Forced displacement is a permanent feature of the global landscape, and Europe is no stranger to it. In fact, according to the UNHCR’s The State of The World’s Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action, more than 40 million people were displaced within Europe as a result of World War II. Smaller but very substantial numbers of people have also been displaced due to conflict and political upheaval in the decades since. Failed uprisings against Soviet rule in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, the Algerian War of Independence, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent return of over 2 million aussiedler (ethnic Germans) to Germany between 1991 and 2014, German reunification, and the disintegration of Yugoslavia have all led to large-scale migration and refugee flows.

Contemporary flows

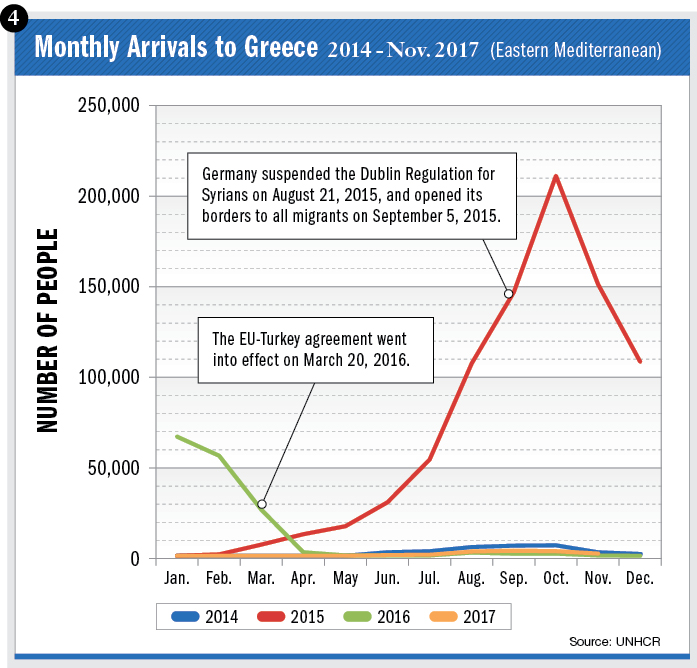

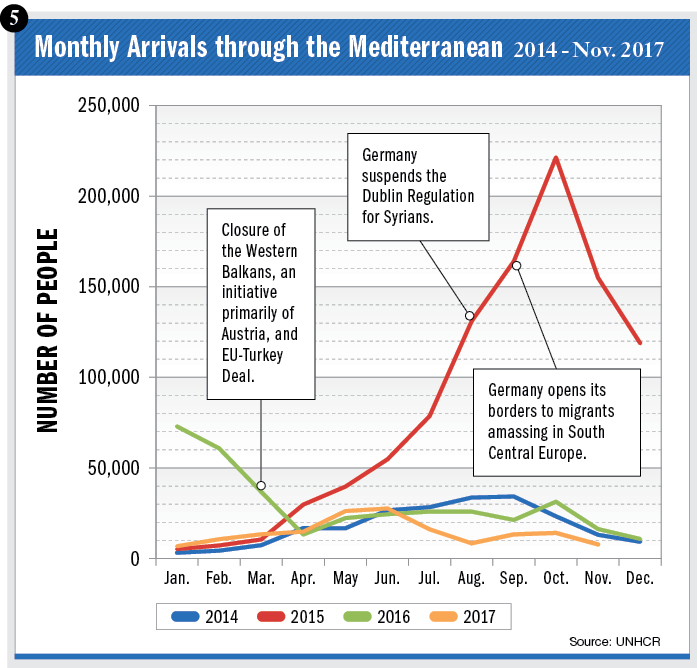

While many of the crises that gave rise to the mass migration and refugee flows over the last century were on European soil and dealt with Europe’s own unresolved political and ideological issues, the latest migration crisis, which began in earnest in 2014, is a result of another facet of Europe’s history: its colonial and post-colonial legacies in the Middle East and Africa. The vast majority of migrants reaching Europe illegally in recent years have entered via three Mediterranean routes (see Figures 3, 4, 5): the western Mediterranean (from the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla on the Moroccan coast or directly to the Spanish mainland); the central Mediterranean (from Libya and Tunisia to Malta or Italy); and the eastern Mediterranean (from Turkey to Greece, almost exclusively through the Aegean Islands, as well as to northern Greece [Thrace], Bulgaria or Cyprus).

According to Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, flows across the central Mediterranean nearly quadrupled from 2013 to 2014, from 45,000 to more than 170,000, bringing the total number of migrants reaching Europe via all Mediterranean routes that year to 230,000. Flows increased exponentially in 2015, peaking at well over 1 million, including more than 885,000 who crossed the eastern Mediterranean route alone. The numbers decreased dramatically in 2016 due to two mutually reinforcing policy initiatives: the early spring closure of the Western Balkan route to Central Europe, and the EU-Turkey deal. Frontex recorded approximately 375,000 Mediterranean crossings for 2016, with the eastern Mediterranean being most popular in the year’s early months and the central Mediterranean becoming dominant the rest of 2016. And data from the UNHCR’s “Operational Portal Refugee Situations: Mediterranean Situation,” indicate that as of November 30, 2017, more than 160,000 people had reached Europe via all Mediterranean routes. Compared to the other two routes, the western Mediterranean route has been relatively quiet in recent years, contributing an estimated 63,000 arrivals for the 2014-17.

According to Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, flows across the central Mediterranean nearly quadrupled from 2013 to 2014, from 45,000 to more than 170,000, bringing the total number of migrants reaching Europe via all Mediterranean routes that year to 230,000. Flows increased exponentially in 2015, peaking at well over 1 million, including more than 885,000 who crossed the eastern Mediterranean route alone. The numbers decreased dramatically in 2016 due to two mutually reinforcing policy initiatives: the early spring closure of the Western Balkan route to Central Europe, and the EU-Turkey deal. Frontex recorded approximately 375,000 Mediterranean crossings for 2016, with the eastern Mediterranean being most popular in the year’s early months and the central Mediterranean becoming dominant the rest of 2016. And data from the UNHCR’s “Operational Portal Refugee Situations: Mediterranean Situation,” indicate that as of November 30, 2017, more than 160,000 people had reached Europe via all Mediterranean routes. Compared to the other two routes, the western Mediterranean route has been relatively quiet in recent years, contributing an estimated 63,000 arrivals for the 2014-17.

Over 70 percent of those arriving on Europe’s shores in 2017 went to Italy. They were largely single men, hailing from primarily Sub-Saharan African countries, but also Bangladesh. The UNHCR reported that unaccompanied children constituted about 13 percent of arrivals to Italy (more than 14,600 in the first 10 months of 2017). By contrast, 2017 entries through the eastern Mediterranean included larger shares of families seeking to reunify with relatives who had already entered Europe. They came from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and, more recently, countries such as Algeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, pointing to the constant reorientation of flows.

National asylum systems

While Italy and Greece have been the entry points for almost all migrants to Europe in recent years, the overwhelming proportion of arrivals intend to move on to other European countries, primarily in Central and Northern Europe and, more specifically, Germany and Sweden. Despite such intentions, the hardening of EU internal borders and the failure of the European Commission-inspired relocation scheme have meant that most migrants and asylum-seekers arriving in Europe post-spring 2016 remain in Italy and Greece, leading to large increases in asylum applications in these countries and even larger adjudication backlogs.

The EU response

A key component of the EU response to the chaotic arrivals through the Aegean during the second half of 2015 and first quarter of 2016 has been the EU-Turkey “statement,” a deal that went into effect in March 2016. The deal was negotiated directly between the Turkish prime minister and the German chancellor and was presented pretty much as a fait accompli to fellow EU heads of government. The deal focused on stemming the flow of migrants arriving via Turkey — the primary route of arrivals at the time — by preventing illegal crossings of the Aegean and promoting a resettlement program from that country. Together with the Austria-led closure of the Western Balkan route, which virtually shut down opportunities for migrants to continue to Central Europe, the EU-Turkey deal reduced entries through the Aegean to between 1,500 and 2,000 people per month until the late summer months of 2017. In return for Turkey’s cooperation, the EU agreed to dramatically scale up its assistance for Syrians in Turkey, focusing on improving their job opportunities and educating their children, thus creating meaningful incentives for them to stay in that country.

An additional aim of the statement was to persuade reluctant EU members to participate in an expanded refugee resettlement program that would promote “legal, safe, and orderly” migration, a policy area in which the EU has barely participated, and to generate interest in a deeper, global response to resettlement. Moreover, Turkey was offered the opportunity to realize its long-term objectives of visa-free entry into Europe for its citizens (after meeting certain criteria) and resuming progress toward EU membership (another major policy priority of successive Turkish governments). The deal also created opportunities for Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to advance his ambition to be seen and treated as the indispensable actor in the region, to advance his policy objectives regarding the Syrian conflict, and to change the Turkish constitution to create a powerful presidential system of government with him at the helm.

An additional aim of the statement was to persuade reluctant EU members to participate in an expanded refugee resettlement program that would promote “legal, safe, and orderly” migration, a policy area in which the EU has barely participated, and to generate interest in a deeper, global response to resettlement. Moreover, Turkey was offered the opportunity to realize its long-term objectives of visa-free entry into Europe for its citizens (after meeting certain criteria) and resuming progress toward EU membership (another major policy priority of successive Turkish governments). The deal also created opportunities for Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to advance his ambition to be seen and treated as the indispensable actor in the region, to advance his policy objectives regarding the Syrian conflict, and to change the Turkish constitution to create a powerful presidential system of government with him at the helm.

The success of the resulting bargain in fulfilling the two parties’ major stated and unstated goals has been significant, if mixed. Flows from Turkey to Greece dropped dramatically (meeting the EU’s principal aim), and significant progress has been made in improving opportunities for Syrians in Turkey. But relatively few migrants have been returned to or resettled from Turkey, and many nongovernmental organizations and almost all activists claim that key ethical issues remain unresolved. From Turkey’s perspective, Erdoğan’s personal ambitions have been fully met while his aspirations involving Syria have attained considerable progress, even if aided by Russia and Iran.

Integration challenge

Integration policy is where the rubber meets the road when it comes to all forms of immigration, regardless of the route or regulatory channel through which newcomers arrive. Success in this policy arena bears enormous dividends for individuals and their families, but also for the communities in which they settle. Failure, however modest or episodic, feeds the narrative of unassimilability of newcomers and fuels political divisions and mistrust toward government.

With the acute phase of the migration crisis behind them, the handful of states most affected by it have moved beyond emergency response mode and are focusing with remarkable vigor on the most unavoidable of the crisis’ governance challenges: the integration of newcomers. Beyond the immediate needs of adequate reception services and timely adjudication of claims, integration is — and will remain for the next decade and beyond — the dominant issue for new arrivals and host populations alike.

The reasons are clear. All too often, some migrant groups and their offspring lag behind natives in language ability, educational achievement, access to and settling into the labor market, and social and political engagement, leading to debilitating cumulative disadvantages. Such disadvantages often express themselves in various forms and degrees of economic, social and political marginalization — leading migrant communities to feel aggrieved and native-born communities to view migrants and their children with impatience, if not wariness and mistrust. Successful integration that is both visible and measurable is thus critical for the well-being of migrants, and community cohesion, and reduces the incidence of anomie that one notices among some immigrants and immigrant-background communities. Successful integration also builds trust in the government’s ability to effectively manage migration, something that is in very short supply in most countries.

The need for thoughtful and intense policy activism reflects a simple reality: The massive inflows have created enormous capacity problems that need to be addressed smartly to effectively confront integration challenges and avoid the longer-term pathologies of earlier efforts. And the challenges are enormous. Newcomers’ educational levels are uneven and far lower than initially thought, a function of the enthusiastic, if not willful, representations of activists and the press. Furthermore, much of that education is inconsistent with the needs and expectations of employers in Europe’s advanced economies. Health needs, particularly mental health issues stemming from trauma, are also massive and need to be adequately addressed. Successful integration into labor markets, a key integration measure, as well as underemployment and brain waste, are ever-present concerns. As a result, the specter of repeating the intergenerational exclusion and disadvantage of some earlier immigrant groups is front and center. Clearly, the scale and scope of the issue necessitate strong investments and an evidence-based, comprehensive approach to integration — a lesson that several of the worst-affected destination countries appear to have internalized. As put forth in a paper co-written by this author and Meghan Benton, “Towards a Whole-of-Society Approach to Receiving and Settling Newcomers in Europe,” the key elements of that approach are:

The need for thoughtful and intense policy activism reflects a simple reality: The massive inflows have created enormous capacity problems that need to be addressed smartly to effectively confront integration challenges and avoid the longer-term pathologies of earlier efforts. And the challenges are enormous. Newcomers’ educational levels are uneven and far lower than initially thought, a function of the enthusiastic, if not willful, representations of activists and the press. Furthermore, much of that education is inconsistent with the needs and expectations of employers in Europe’s advanced economies. Health needs, particularly mental health issues stemming from trauma, are also massive and need to be adequately addressed. Successful integration into labor markets, a key integration measure, as well as underemployment and brain waste, are ever-present concerns. As a result, the specter of repeating the intergenerational exclusion and disadvantage of some earlier immigrant groups is front and center. Clearly, the scale and scope of the issue necessitate strong investments and an evidence-based, comprehensive approach to integration — a lesson that several of the worst-affected destination countries appear to have internalized. As put forth in a paper co-written by this author and Meghan Benton, “Towards a Whole-of-Society Approach to Receiving and Settling Newcomers in Europe,” the key elements of that approach are:

Pursuing a comprehensive, whole-of-government strategy that centers on employment: Governments must develop systems for identifying employment skills and needs as early as possible, make it easier for newcomers to gain on-the-job language and work skills, and invest in alternative livelihoods programs, such as voluntary work programs and entrepreneurship.

Building society-wide integration systems: Successful integration requires that host communities be engaged organically. This entails brokering new partnerships with a range of stakeholders, including investors, social entrepreneurs and employers, as well as stimulating innovation in the delivery of needed services. However, in doing so, governments should aim to provide mainstreamed services and make the public feel consulted and be an integral part of the overall effort.

Managing social change and regaining public trust: Inclusive national narratives around integration and how to deliver good integration outcomes are essential. Moreover, building the necessary capacity to deliver the needed services is crucial to alleviating concerns that governments are not managing migration well and that the asylum system is being abused.

Key observations

Europe’s responses to the ongoing migration and asylum crisis continue to be uneven. The August 2017 mini-summit in Paris involving French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, and the heads of Chad, Niger and the Libyan government only served to punctuate that point despite the rhetoric surrounding it. Such efforts tend to emphasize the EU’s disunion and punctuate the fact that its members must make their own way in managing the crisis and its consequences. In this last regard, Italy’s recent insistence that nongovernmental organizations engaged in search-and-rescue operations in the central Mediterranean observe a code of conduct designed to discourage migration — and agreements with Libya and Tunisia to prevent migrants from getting onto boats and forcibly return such boats to ports before they leave each nations’ waters — appear to be turning that part of the migration tide. Fewer migrants have arrived in Italy since the summer of 2017, and as a result, the number of deaths in transit dropped dramatically — although the share of deaths per arrival has not.

It is clear that the EU members affected most directly by the 2015 flows are determined not to have a repeat of that year, and no European country seems to be more determined than Germany. The Italian deal with the Libyan and Tunisian governments, which clearly has the support of the EU members that met in Paris, could signal significant changes in the EU’s approach to controlling cross-Mediterranean flows. It might be another step toward reconsidering the practice of bringing rescued migrants to Europe, and toward testing the idea of establishing multiple offshore asylum processing points where preliminary decisions about asylum claims could be made. It may be too premature, however, to suggest that the Italian agreements will dramatically reduce flows through the central Mediterranean over the longer term. Accomplishing that would require at least two other politically hard-to-do things: allowing very few people to lodge claims in Europe, and instituting a robust resettlement program. Only time will tell which direction these newest and, so far, mostly rhetorical initiatives will take.

It is clear that the EU members affected most directly by the 2015 flows are determined not to have a repeat of that year, and no European country seems to be more determined than Germany. The Italian deal with the Libyan and Tunisian governments, which clearly has the support of the EU members that met in Paris, could signal significant changes in the EU’s approach to controlling cross-Mediterranean flows. It might be another step toward reconsidering the practice of bringing rescued migrants to Europe, and toward testing the idea of establishing multiple offshore asylum processing points where preliminary decisions about asylum claims could be made. It may be too premature, however, to suggest that the Italian agreements will dramatically reduce flows through the central Mediterranean over the longer term. Accomplishing that would require at least two other politically hard-to-do things: allowing very few people to lodge claims in Europe, and instituting a robust resettlement program. Only time will tell which direction these newest and, so far, mostly rhetorical initiatives will take.

Conclusion: A never-ending story

As the sense of crisis has subsided, it is integration concerns that have become the focus of governments and much of the public. But the anxiety about flows remains. At its root is a fear of the return of large-scale, spontaneous migration, and unease over the cultural and identity issues raised by the backgrounds of the mostly Muslim newcomers. These worries play readily into the hands of populist parties and make for volatile politics, particularly as mainstream parties adopt key elements of the populist agenda in a classic effort to deny them as much political space as possible.

The first form of anxiety is easy to understand. The speed and chaotic way flows grew brought to the fore long-simmering national identity insecurities and apprehensions and, in the last two years, domestic security concerns (terrorism). Adding to this anxiety is that most newcomers come from countries with significant social, cultural, ethnic and religious differences. Similarly, the increasing visibility and “otherness” of most newcomers has fueled further discomfort among host populations and has shaped reactions to the newcomers. As a result, the migration crisis has stimulated ever-present concerns about uncontrolled social and cultural change and the efficacy of the receiving societies’ management models.

When more definitive accounts of the ongoing crisis are written, two sets of questions will be the likely focus: how well (or poorly) the newcomers have integrated and whether Europe, or more precisely its strongest states, have found a way to replace the migration disorder of the past few years with policies that insist on safe, legal and orderly entries, in large part by performing the harder tasks that governments are elected to do: securing borders and enforcing laws; examining individual claims for asylum carefully but expeditiously; severely limiting the use of subsidiary protection; removing failed asylum applicants and illegal (economic) migrants; and reducing dramatically the opportunities for migrants to game the system. These countries must also make real progress in determining the parameters of their responsibilities toward their neighborhood and how to properly implement them.

At the heart of these decisions must be a realization that the primary responsibility of sovereign and well-governed nations is toward their own electorates and communities, a focus that the migration crisis has made elusive. Such a realization demands that these governments, and societies, actively seek and find the most appropriate equilibrium point along the continuum of values and interests. These are the true challenges that Europe’s states must confront and resolve wisely. And their resolution, or lack thereof, will determine whether the past few years will prove to be a new normal or a black swan event.

Comments are closed.