Greece and Italy are the main points of entry, but not the ultimate destinations of migrants

By Lt. Cmdr. Ioannis Argyriou and Military Judge Christos Tsiachris

Migration is one of the global challenges of the 21st century. It cannot be defined in its totality because its causes and parameters are influenced and changing based on the conditions prevailing at the time. In general, migration is the movement of a person from one area of residence to another. In many cases, migration involves the movement of large numbers of people, earning it the term “mass migration.” Migration in general, particularly mass migration, has geopolitical, humanitarian, social, political and economic dimensions.

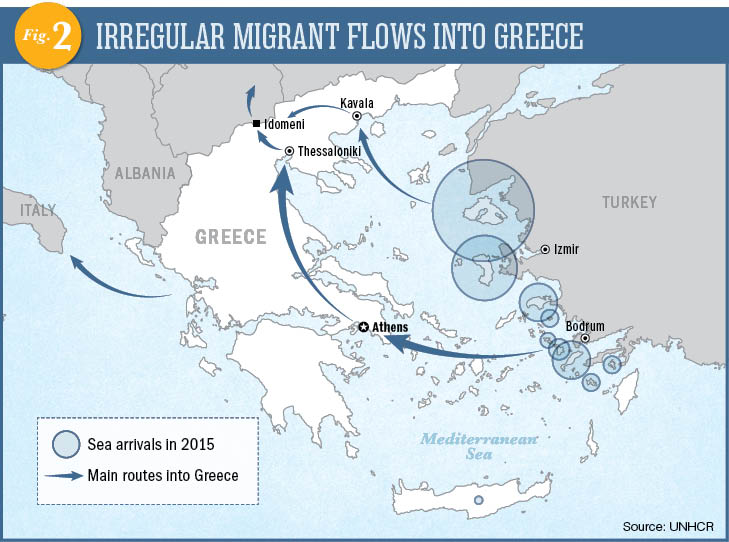

Recently, Europe — especially Greece and Italy as gateways to Europe from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region — has been placed at the heart of this global issue because of its exposure to mixed migration (immigrants and refugees). However, due to the width and volume of mixed migration and the fact that the final destinations of immigrants and refugees are the countries of Central and Northern Europe, the phenomenon has taken on a pan-European dimension.

Recently, Europe — especially Greece and Italy as gateways to Europe from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region — has been placed at the heart of this global issue because of its exposure to mixed migration (immigrants and refugees). However, due to the width and volume of mixed migration and the fact that the final destinations of immigrants and refugees are the countries of Central and Northern Europe, the phenomenon has taken on a pan-European dimension.

Definitions

To discuss migration, one should first distinguish people who move from one area of residence to another, mainly according to the motivation of their movement. By adopting internationally accepted legal standards and definitions, these people can be categorized into refugees, internally displaced people (IDPs) or immigrants (legal/documented or illegal/undocumented), as following:

Refugees: According to Article 1(A)2 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, the term “refugee” shall apply to any person, who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” In this light, according to the Geneva Academy, refugees are defined by three basic characteristics: (1) they are outside their country of origin or outside the country of their former habitation; (2) they are unable or unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of that country because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted; and (3) the persecution feared is based on at least one of five grounds: race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.

IDPs: Unlike refugees, IDPs do not cross an international border to find sanctuary but remain inside their home countries. Even if they fled for similar reasons as refugees (armed conflict, generalized violence, human rights violations), IDPs legally remain under the protection of their own government, even though that government might be the cause of their flight. As citizens, they retain all of their rights and protections under both human rights and international humanitarian law, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) states.

Immigrants: Immigration is governed primarily by the domestic laws of each state and secondarily by relevant international, regional and bilateral treaties, international and regional resolutions, declarations and other instruments. The term “immigrant” applies to people who immigrate legally, while those who immigrate illegally are considered trespassers of borders. In other words, people who immigrate following the immigration laws of a state are considered legal/documented immigrants, while people who cross the land or sea borders of a state without being refugees and without following its immigration laws are considered illegal/undocumented immigrants.

Immigrants: Immigration is governed primarily by the domestic laws of each state and secondarily by relevant international, regional and bilateral treaties, international and regional resolutions, declarations and other instruments. The term “immigrant” applies to people who immigrate legally, while those who immigrate illegally are considered trespassers of borders. In other words, people who immigrate following the immigration laws of a state are considered legal/documented immigrants, while people who cross the land or sea borders of a state without being refugees and without following its immigration laws are considered illegal/undocumented immigrants.

Special reference should be made to mixed migration flows. “Mixed flows” are defined by the International Organization for Migration as “complex population movements including refugees, asylum-seekers, economic migrants and other migrants.” In essence, mixed flows concern irregular movements frequently involving transit migration, where people move without the requisite documentation, crossing borders and arriving at a destination without authorization. This is the case that Europe currently faces: mixed migration flows consisting of refugees and illegal/undocumented immigrants.

Mixed migration flows to Europe

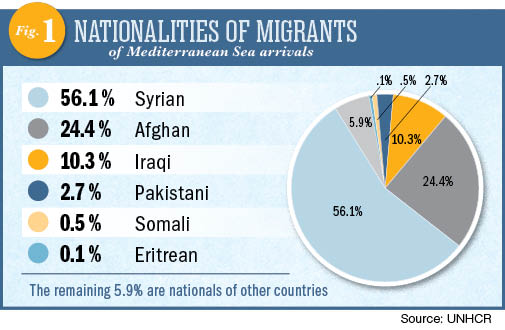

Greece According to data collected by the UNHCR, refugee and immigrant flows into Greece in 2015 sharply increased over previous years. The total number of refugees and immigrants who arrived in Greece in 2015 rose to 851,319. It is equally important to examine their countries of origin. The nationality of the refugees and immigrants who arrived in Greece in 2015, according to the Hellenic Coast Guard and the Hellenic Police, are shown in Figure 1.

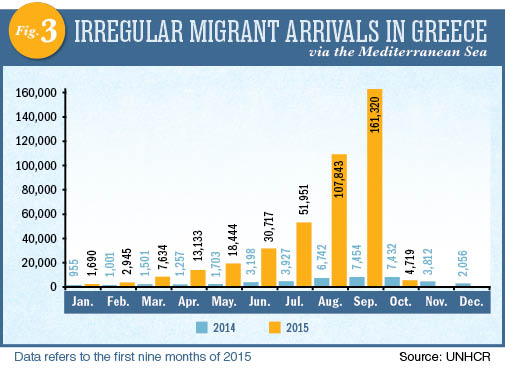

Regarding the gender and age of immigrants and refugees, the UNHCR reports 66 percent are men, 13 percent are women and 21 percent are children. Additionally, Figure 3 shows the number of arrivals per month for 2014 and 2015, highlighting the rapid increase in 2015, which peaked in September 2015 with 161,320 migrants arriving in Greece across the Mediterranean, an increase of 8,557 percent compared to the same month in 2014. Another important factor to consider is that these figures do not include arrivals across Greek land borders.

To understand the magnitude of the influx, the overall flow of immigrants and refugees should be compared to the population of the Greek islands of the eastern Aegean Sea, which totals about 400,000. These islands are the entry points for thousands of refugees and immigrants to Europe.

Italy According to data collected by the UNHCR, the flows of refugees and immigrants into Italy increased sharply from 2014 to 2016. Mixed migration flows continue to grow. The number of refugees and immigrants who entered Italy by sea rose from 2,171 in January 2014 to 3,528 in January 2015 and 5,273 in January 2016.

Italy According to data collected by the UNHCR, the flows of refugees and immigrants into Italy increased sharply from 2014 to 2016. Mixed migration flows continue to grow. The number of refugees and immigrants who entered Italy by sea rose from 2,171 in January 2014 to 3,528 in January 2015 and 5,273 in January 2016.

The nationalities of refugees and immigrants who arrived in Italy in 2015 and 2016 are different from Greece. In January 2015, the majority of refugees and immigrants were Syrians, while in January 2016 the majority were Africans. In January 2016, people originating from 40 different countries arrived in Italy, and nearly half of these arrivals came from just four countries: The Gambia, Guinea, Nigeria and Senegal. Remarkably, only six Syrians arrived in Italy by sea in January 2016.

Comparing Greece and Italy

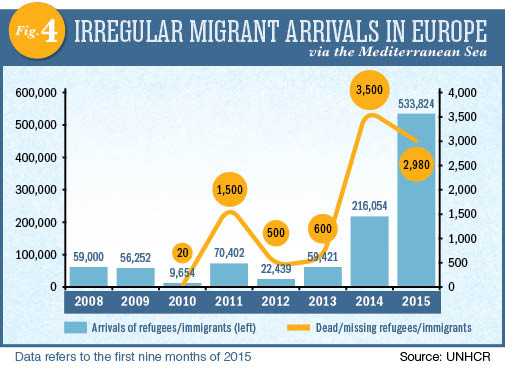

As depicted in Figure 4, refugee and immigrant arrivals across the Mediterranean into Europe reached 533,824, constituting an increase of 147 percent compared to 2014. According to the data, 75 percent (400,387) arrived in Greece, 24.5 percent (131,000) in Italy and only 0.5 percent (2,338) in Spain. The vast majority of refugees and immigrants who enter Greece and Italy depart from Turkey and Libya, respectively.

In 2015, mixed migration flows in the Mediterranean shifted largely from Italy to Greece. This shift was accompanied, in parallel, with a great increase in migration and with fewer deaths and missing persons compared to 2014, according to UNHCR data.

Causes of mixed migration flows

There are several causes for the mixed migration phenomenon, but two are most important:

First, the discrepancy in living standards between the poorer African and Asian countries of most immigrants’ and refugees’ origin and that of richer European destination countries. The failure of some countries to provide the basics of life, such as food, water, lodging, education and health services, is the main factor pushing a large part of their populations to emigrate. Additionally, the pursuit of better jobs and money is a main motivator.

Second, state instability, authoritarian regimes, internal strife and armed conflicts prevailing in many countries force more and more individuals and groups to seek safer countries. For example, thousands of migrants come from Syria, where the war has forced a large part of the population to move within or outside the country.

Consequences of mixed migration

Migration flows seem to affect destination countries directly by stressing economies (including the unemployment rate), education, health services, and political and cultural conditions. Many fear that migrant populations will alter the religious and cultural mores of European nations by changing their demographic balance. Concerns have also been expressed about security issues caused by migration. Along with the nationwide dimensions, the impacts on local communities are also significant. Vast migration greatly affects the smooth functioning of trade and production. Indeed, the impact of migration on economic activity is highly visible in the tourism industry, which shows significant losses in areas where refugees/immigrants arrive in mass.

Managing mixed migration to Europe

Managing mixed migration to Europe

The management of increased mixed migration flows — in parallel with humanitarian, social and geopolitical dimensions — has an important budgetary dimension. There are three main phases of managing this phenomenon:

In the first phase, the country acting as the first point of reception manages arrivals and provides temporary accommodation and care.

In the second phase, the country acting as a temporary place of establishment, manages the (temporary) accommodation of arriving migrants and creates safe conditions until their status of hosting is clarified (e.g., applications by asylum seekers).

In the third phase, the country acting as a permanent place of establishment manages the integration of immigrants and refugees according to its migration policy.

Greece is in the first management phase of increased mixed migrations flows, during which the country is regarded by arriving immigrants and refugees as a place of first reception on their journey to final destinations in Central and Northern Europe. Management of this phenomenon is handled by the competent agencies of the central administration, such as the Hellenic Coast Guard, the Hellenic Police, regional and municipal services, hospitals and other health infrastructure, the Hellenic Armed Forces, several information operations, nongovernmental organizations, civil protection voluntary organizations and

citizens’ initiatives.

In the first phase, the main actions, benefits and management procedures are codified as following:

Search and rescue of immigrants and refugees conducted mainly by the Hellenic Coast Guard, the Hellenic Police and volunteer lifeguards.

Registration and identification of immigrants and refugees conducted by the Hellenic Police and provision of first reception services by the agencies of competent ministries in the so-called hot spots.

Creation and maintenance of (new) reception (hot spots) and hosting sites (relocation camps) for immigrants and refugees through relevant supplies and connections to networks.

Safeguarding of public order by the Hellenic Police.

Provision of health services by hospitals, primary health structures and voluntary organizations.

Provision of basic necessities (food, clothing, hygiene items, etc.).

Maintenance of living conditions (chemical toilets, waste bins, etc.) in temporary lodging called relocation camps.

Transfer of immigrants and refugees both within the islands and in/to mainland Greece.

Provision of large-scale services (cleaning, administration, infrastructure maintenance, etc.) by the regional and municipal agencies and their administrative and

technical staff.

Italy

Italy, like Greece, is in the first management phase of mixed migration flows and follows more or less the same strategy. Although some refugees and immigrants wish to stay permanently in Italy, most regard Italy as a place of first reception. Their aim, too, is to head farther north.

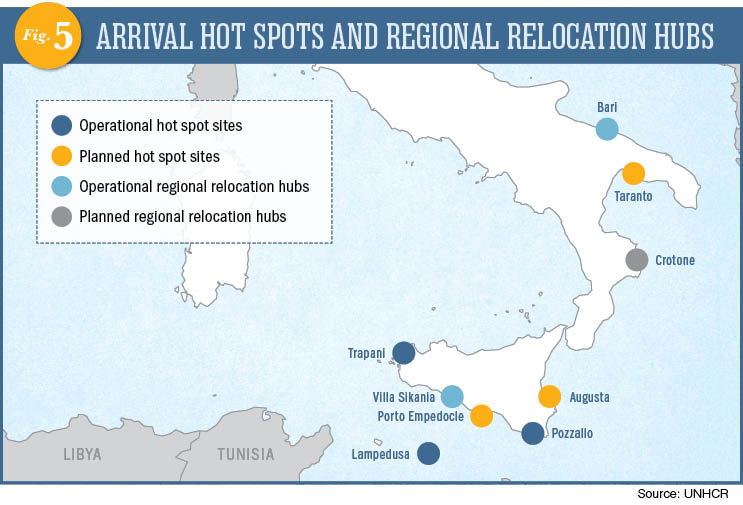

In response to increased mixed migration flows, the Italian government launched Operation Mare Nostrum on October 18, 2013. It lasted until October 31, 2014, when it was superseded by Frontex’s Operation Triton. Frontex operates under the command of the Italian Ministry of Interior, in cooperation with the Guardia di Finanza and Italian Coast Guard. The mission of both operations was the search and rescue of refugees and immigrants and border security, including the arrest of smugglers. The Italian government has established the National Coordination Group and engages the Ministry of Interior, the Navy, the Coast Guard and other governmental services in the management of mixed migration flows. It is also assisted by Europol, Eurojust, European Asylum Support Office and UNHCR. According to UNHCR, in January 2016, Italy ran hot spot sites in Lampedusa, Trapani and Pozzallo, and relocation hubs in Villa Sikania and Bari, while planning to run more in the near future, as seen in Figure 5.

Conclusion

Managing mixed migration flows is a great challenge for European countries, especially for Greece and Italy, the first points of reception for the majority of refugees and immigrants. The extent and volume of the aforementioned flows makes it impossible for Greece and Italy to afford the costs on their own. Assistance from the remaining European Union member states is a must in order to achieve: 1) high standards of immigrant integration, if integration is the final aim of EU member states, and 2) the protection of refugees, which is a duty deriving from international law.

Moreover, the European legal system demands that human rights be protected, irrespective of people’s status as refugees or illegal/undocumented immigrants. Nevertheless, refugees should be distinguished from illegal immigrants so that they can enjoy the full scope of rights allotted to them under international refugee law.

Comments are closed.