21st Century Warfare Requires 21st Century Deterrence

By Col. Jeffrey W. Pickler, U.S. Army

Introduction

After World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union found themselves competing for power and influence throughout the world. As the Soviet Union consolidated its control over the territory it occupied and the U.S. supported economic and political reform in Western Europe, a different type of war emerged. In contrast to previous wars, which saw hundreds of divisions fighting across thousands of miles of battlefields, peace was now kept not only by the presence of large military formations, but also by the presence of nuclear weapons. The risk of escalation to a conflict greater in scope and scale than ever witnessed led to a “Cold War,” with both countries competing below the threshold of traditional conflict. To help prevent the Cold War from becoming “hot,” the U.S. adopted a policy of deterrence.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) defines deterrence as the “prevention of action by the existence of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction and/or belief that the cost of action outweighs the perceived benefits.” Effective deterrence requires the capability, will and ability to communicate to counter an adversary’s activities through the threat of denial or punishment. Conventional and nuclear deterrence would be the focal point for U.S. security for the next 50 years as the U.S. sought to achieve its strategic objectives while preventing a full-scale war.

Most analysts agree that deterrence prevented a global war between the superpowers. However, deterrence did not end strategic competition between the U.S. and the Soviet Union; it simply pushed it into areas that limited the risk of triggering an “unacceptable counteraction.” While both superpowers used irregular warfare tactics to achieve strategic objectives, technological limitations consequently minimized the effectiveness and impacts of these tactics. This is no longer the case. The pace of technological change, an interconnected global network and a ubiquitous information environment provide opportunities for states to achieve strategic objectives below the threshold of conventional war. From the Baltics to the Caucuses, Russia has repeatedly demonstrated how subconventional actions can achieve strategic objectives without fear of an unacceptable counteraction. Russia has incorporated changes in the global environment into a strategy in which cost, attribution and risk of escalation are minimized. Therefore, a deterrence policy focused solely on conventional and nuclear forces is no longer sufficient for limiting Russian aggression.

In his reflections on deterrence in the 21st century, former NATO Deputy Secretary General Alexander Vershbow noted that deterrence “requires effective, survivable capabilities and a declaratory posture that leave the adversary in no doubt that it will lose more than it will gain from aggression, whether it is a short-warning conventional attack, nuclear first use to deescalate a conventional conflict, a cyber-attack on critical infrastructure, or a hybrid campaign to destabilize allies’ societies.” Current U.S. deterrence posture does not consider the 21st century operational environment. For deterrence to remain viable, it must be expanded to address conventional and subconventional attacks.

The Evolution of Deterrence

American nuclear strategist Bernard Brodie famously wrote, “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them.” Following World War II, the U.S. military began a massive demobilization. The country wanted a peace dividend following the nearly $4 trillion in military spending during World War II, which consumed 36% of U.S. gross domestic product, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service. The U.S. compensated for a shrinking military through its monopoly on nuclear weapons and alliances such as NATO, which counts “deterring Soviet expansionism” as a primary reason for its creation. These changes in the strategic environment led the U.S. to adopt a policy of deterrence based on a small conventional military, a strong alliance system and a growing arsenal of nuclear weapons.

Deterrence theorist Thomas Schelling argued that deterrence is not about war, but the “art of coercion and intimidation.” Deterrence theory recognizes two basic approaches. Deterrence by denial is based on an ability to deter actions by making them either infeasible or unlikely to succeed. Deterrence by punishment threatens severe penalties, whether lethal, economic or informational, should an attack occur. Fundamental to both are clearly defined national interests, or “red lines,” typically highlighted in national security documents and communicated by leadership. Schelling argued that an effective deterrence policy must combine the capability and willingness to win at all levels of escalation with a potential adversary, while maintaining open communication channels in order to deliver clear and direct messages to prevent unintended escalation.

As the administration of U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower evaluated the strategic environment after the Korean conflict, it decided to codify the U.S.’s deterrence strategy given the Soviet Union’s superiority in conventional forces and the growing U.S. nuclear arsenal. First expressed by U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in 1954, this new strategy communicated a threat of “direct, unrestrained nuclear response of massive scale in case of communist aggression, possibly aimed at the very centers of the enemy’s economic life.” This view was formalized in National Security Policy Paper 162/2. It outlined the need to maintain “a strong military posture, with emphasis on the capability of inflicting massive retaliatory damage by offensive striking power.” This “Massive Retaliation” strategy was based on “deterrence by punishment,” allowing the U.S. to negate the Soviet Union’s conventional numerical advantage by possessing the capability, and clearly communicating the will, to inflict an unacceptable cost should the Soviet Union or any other potential aggressor initiate any action which threatened U.S. national interests.

As the Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the U.S. and both powers further developed their arsenals and capabilities, the U.S. was forced to reconsider the effectiveness of its deterrence policy. Massive Retaliation changed to “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD), but critics labeled MAD a geopolitical suicide pact that limited national leadership’s ability to control the escalation of all emerging crises. Retired U.S. Army Chief of Staff Maxwell Taylor sharply criticized the U.S. reliance on nuclear deterrence for deterring and responding to limited forms of war. The strategic environment had again changed, and the U.S. needed to change its military strategy to better facilitate deterrence. After John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, he established a “Flexible Response” strategy that sought to provide a number of military and nonmilitary options to provocations. Flexible Response later evolved into “Flexible Deterrent Options,” which remains a component of contemporary military doctrine. It is defined in Joint Publication 5-0 as “preplanned, deterrence-oriented actions tailored to signal to and influence an adversary’s actions.” The intent behind Flexible Deterrent Options is to leverage all elements of national power to de-escalate an emerging crisis and avoid provoking full-scale combat. Both Flexible Response and Flexible Deterrent Options recognized that deterrence strategies must include more than the threat of nuclear annihilation, but neither adequately addressed subconventional threats.

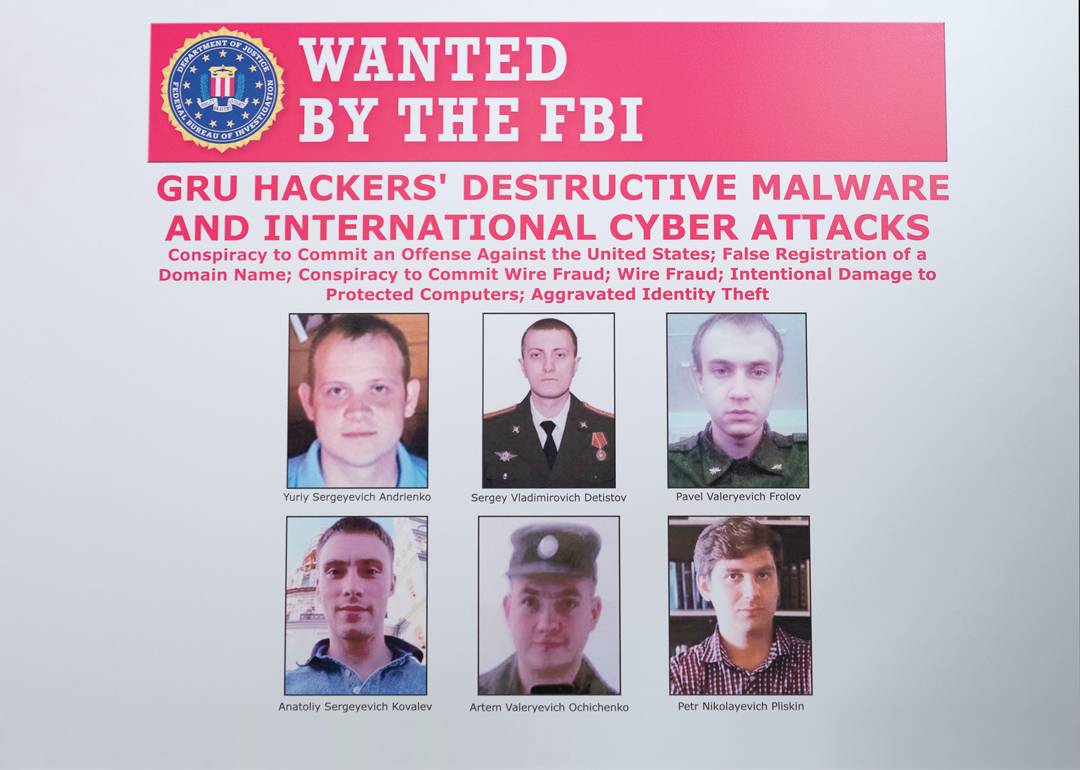

Cold War deterrence was effective because the U.S. strategy prevented large-scale conflict between major powers and kept adversarial competition below the threshold of war. In an article for “War on the Rocks,” Michael Kofman writes: “Effective nuclear and conventional deterrence has long resulted in what Glenn Snyder described as a stability-instability paradox. This holds that the more stable the nuclear balance, the more likely powers will engage in conflicts below the threshold of war.” This was true during the Cold War and remains true today. A U.S. State Department report from 1981 highlights actions taken by the Soviet Union in the Cold War, including “control of the press in foreign countries; outright and partial forgery of documents; use of rumors, insinuation, altered facts, and lies; use of international and local front organizations; clandestine operation of radio stations; exploitation of a nation’s academic, political, economic, and media figures as collaborators to influence policies of the nation.” However, these efforts failed to achieve any significant strategic impact due to limitations of technology and the geopolitical environment at the time. Today, the strategic environment has again changed, and these types of actions have a greater effect on U.S. national security. Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the 2020 SolarWinds data breach show that our adversaries can accomplish strategic objectives in the subconventional environment. Therefore, it is time to reevaluate strategies to foster deterrence and ensure it remains relevant in the 21st century.

Deterrence in the Current Strategic Environment

The 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy states that the DoD’s “enduring mission is to provide combat-credible military forces needed to deter war and protect the security of our nation.” This suggests that the same Cold War strategy will deter contemporary threats. However, as Mark Galeotti notes in his recent book, “The Weaponisation of Everything”:

“The world is now more complex and above all more inextricably interconnected than ever before. It used to be orthodoxy that interdependence stopped wars. In a way, it did — but the pressures that led to wars never went away, so instead interdependence became the new battleground. Wars without warfare, non-military conflicts fought with all kinds of other means, from subversion to sanctions, memes to murder, may be becoming the new normal.”

This interconnectedness has changed the strategic environment and undermines our current deterrence strategy. “Taken together,” Andrew F. Krepinevich Jr., writes in a 2019 article in “Foreign Affairs,” “these developments lead to an inescapable — and disturbing — conclusion: the greatest strategic challenge of the current era is neither the return of great-power rivalries nor the spread of advanced weaponry. It is the decline of deterrence.”

Kofman captured the Russian approach to war, noting, “If war is not an option and direct competition is foolish in light of U.S. advantages, raiding is a viable alternative that could succeed over time. Therefore, Russia has become the guerilla in the international system, not seeking territorial dominion but raiding to achieve its political objectives.” Russia has spent years perfecting this “raiding,” which stands in stark contrast to how the U.S. approaches warfare. Russia effectively coordinates a whole-of-government approach to war and works to integrate all elements of national power to achieve its strategic aims. Its successful subconventional operations cover “the entire ‘competition space,’ including subversive, economic, information, and diplomatic means, as well as the use of military forces,” Mason Clark wrote in a 2008 paper for the Institute for the Study of War. Their military continues to play a critical role as well, adapting their core doctrine to train and equip for these types of operations. Russian Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov noted in 2016 that the “very ‘rules of war’ have changed. The role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness.” In an article for the Modern War Institute at West Point, Sandor Fabian and Janis Berzins describe how this can be seen in Russia’s tactics, which, in some cases, subordinate lethal operations to nonlethal operations.

The U.S. approach to deterrence remains largely the same as during the Cold War. The emphasis is on a conventional and nuclear deterrence model based on advanced weapons systems and capability developments to deter and, if necessary, defeat a peer enemy on the battlefield. The U.S. Army’s current modernization efforts, as described in its “2019 Army Modernization Strategy: Investing in the Future,” prioritize battlefield lethality, with billions of dollars being poured into long-range precision fires, next generation combat vehicles, future vertical lift platforms, the modernization of army network technologies, air and missile defense systems, and increasing the capability of individual weapons. The U.S. Army’s Combat Training Centers continue to train maneuver brigades against a peer threat on a battlefield, assessing each rotational unit’s ability to close with and destroy an “enemy force” through fire and maneuver. Division, corps and theater-level Army warfighter exercises focus largely on each staff’s ability to destroy a peer threat on contested terrain with mass and precision fires. These efforts facilitate conventional deterrence, but as the past 15 years have shown, they do not deter cyberattacks, use of proxies, disinformation campaigns and other forms of subconventional operations that dominate the current strategic environment. On the contrary, current training and procurement initiatives only serve to reinforce Russia’s efforts to combat us where we are not investing our defense budget or focusing our training. As former CIA Director Leon Panetta noted, the “next Pearl Harbor that we confront could very well be a cyberattack that cripples America’s electrical grid and its security and financial systems.” This sentiment is echoed by many other former and current national leaders and reveals their concern that our current deterrence model fails to adequately address these emerging threats.

While conventional and modern nuclear forces continue to provide the foundation of our deterrence model, they are no longer sufficient. Contemporary deterrence requires both military and nonmilitary capabilities to counter adversary tactics. Creating a strategy that deters potential adversaries through both punishment and denial will be crucial to facilitating 21st century deterrence. In the increasingly blurred lines between peace and war, we must be able to clearly articulate an unacceptable cost to subconventional threats aimed at destabilizing our society or threatening critical infrastructure, as we would against a conventional attack or nuclear threat. Vershbow maintains that deterrence will only remain credible if the U.S. has the capability and will to clearly communicate its willingness to punish or deny adversarial actions. The strategic environment has again changed, and our strategy must change with it for deterrence to remain relevant. Some countries, such as new NATO member Finland, have updated their strategies for fostering deterrence because of changes in the operational environment.

Deterrence in Finland

Finland, which gained its independence from Russia in 1918, is an operative example of successful deterrence. The 1,340-kilometer border between Finland and Russia has remained stable in spite of Finland’s military nonalignment. Many analysts believe Finland has maintained its independence and territorial integrity despite its geographic location, and economic and military inferiority, because of its strategy of “Total Defense.” This strategy helps deter Russian conventional provocative actions and subconventional tactics, such as election interference, disinformation and cyberattacks.

Finland’s Total Defense is “a combination of deterrence, resilience, and defensive as well as offensive actions to constrain adversaries’ hybrid activities in all situations,” wrote Finland Defence Forces Brig. Gen. Juha Pyykönen and Finnish security expert Dr. Stefan Forss in a study for the U.S. Army War College. The strategy is an integrated effort that works to educate its citizens and leaders, integrate government agencies with civil society organizations and businesses, and develop the necessary conventional and subconventional capabilities to protect national security. These efforts help ensure that all elements of society and government understand the threats and work together to mitigate them. Finland has a robust conventional capability and routinely conducts large-scale military exercises with NATO and non-NATO forces. It maintains a high state of readiness through specialized “readiness units,” which, according to an article by Michael Peck in “The National Interest,” are led by professional soldiers and are meant to “respond rapidly to a threat, perhaps within hours [and] be deployed nationally [with] sufficient independent firepower and endurance to engage even a well-armed adversary.” This force structure ensures any invading military might accomplish initial gains, but will face a formidable defense in depth, capable of inflicting an unaffordable cost. These efforts, investments, and exercises demonstrate why Finland has one of the highest levels of military spending per capita in Europe.

Finnish subconventional deterrence initiatives focus on a whole-of-society approach by coordinating efforts across governmental and private entities, educating leaders and society on threats, integrating efforts to better deter those threats and developing exercises to demonstrate capabilities across all domains. To counter Russian disinformation, Finland organized a Ministry of Defense Security Committee to link government agencies and nongovernmental entities to bypass typical bureaucratic problems, quickly share information, coordinate responses and keep the Finnish population informed regarding known disinformation efforts. Finland’s schools educate children to spot disinformation almost as soon as they learn how to read. Media and technology literacy education efforts help ensure the entire Finnish society can delineate fact from fiction, fostering government legitimacy. Finland also developed a National Defense Course to educate participants on threats, security and defense policies, and their roles in national security. Realizing the threat from cyberattacks, Finland is a leader in cyber defense and is the home for the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, or Hybrid CoE. The Hybrid CoE includes 31 partner countries from the European Union and NATO and is focused on hybrid threats emanating from Russia and nonstate actors. These efforts demonstrate Finland’s understanding of how to effectively deter subconventional threats.

Many of these same initiatives can be incorporated into the U.S. European Command (EUCOM) to develop a more comprehensive, coordinated, and integrated deterrence model that clearly communicates the capability and will to deter all forms of Russian aggression.

Improving EUCOM’s Ability to Facilitate Deterrence

The U.S. has previously adopted a number of strategies to foster deterrence in changing strategic environments. Today’s strategic environment again requires change to facilitate deterrence. Effective conventional and nuclear deterrence forms the foundation of deterrence, but this effectiveness is also what drove conflict into areas where deterrence did not exist. Our adversaries’ subconventional actions now threaten national security and must be addressed. The new U.S. National Defense Strategy, released in October 2022, notes this challenge and attempts to mitigate it through the concept of “Integrated Deterrence.” U.S. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl explained, “… in terms of integrated … we mean, integrated across domains, so conventional, nuclear, cyber, space, informational [and] integrated across theaters of competition and potential conflict [and] integrated across the spectrum of conflict from high intensity to the gray zone.” Deterrence in the 21st century will only be effective, Lithuanian National Defense Ministry official Vytautas Keršanskas writes in a paper for the Hybrid CoE, “if governments have a specific strategy for each actor they want to deter.” As we seek to better integrate all aspects of national power into deterrence, it is imperative that our policies are based on an adversary’s strategic goals, interests, rationales and vulnerabilities. Within EUCOM’s operational environment, integrated deterrence should include allowing other government entities and business leaders to participate in EUCOM’s planning, operations and exercises, and developing information warfare capabilities that organize, educate and train our personnel to defend against Russian disinformation and cyber activity. These recommendations can be implemented quickly and within EUCOM’s current organizational structure, but most importantly, foster subconventional deterrence by addressing specific vulnerabilities within the operational environment where Russia continues to attack with near impunity.

EUCOM currently develops and rehearses its operational plans through strategic roundtables focused on Russia and chaired by the combatant commander. In October 2021, the then-EUCOM commander, U.S. Air Force Gen. Tod D. Wolters, stated these roundtables “serve an important role in keeping our nation’s senior-most military leaders synchronized both strategically and operationally on key issues related to global campaigning and competition.” Limited in participation to senior military and DoD officials, strategic roundtables omit key stakeholders from industry and other governmental and nongovernmental agencies operating in Europe. Including these additional participants would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the threat and unique perspectives and expertise that would not otherwise be included in a military-only meeting. Akin to Finland’s Ministry of Defence Security Committee and its National Defence University, this recommendation would help develop a more thorough vulnerability assessment, educate participants on Russian subconventional tactics, and develop a whole-of-society approach to increase our understanding of the problems and develop capabilities to more effectively deter them. A challenge to this recommendation is the current classification level for the Russia Strategic Roundtable as “Top Secret.” Incorporating participants without security clearances risks generalizing the discussion to a level that will not be beneficial to any participant. To mitigate this, efforts must be made to declassify as much as possible, while also developing opportunities for those outside of the DoD to receive security clearances so these discussions continue to be worthwhile for all participants.

The information space presents another challenge for subconventional deterrence. The U.S. Government Accountability Office noted in 2021 that “DOD made little progress in implementing its information operations strategy and had challenges conducting information operations.” U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Dennis Crall, the joint staff director for Command, Control, Communications, and Computers/Cyber and chief information officer, stated in February 2022: “Combatant commanders too often think of information operations as an afterthought. We understand kinetic operations very well. Culturally, we distrust some of the ways that we practice information operations. The attitude is to ‘sprinkle some IO on that.’ Information operations need to be used — as commanders do in kinetic operations — to condition a battlefield.” The Congressional Research Service recently described Information Warfare as “as a strategy for the use and management of information to pursue a competitive advantage, including both offensive and defensive operations.” EUCOM must develop an information warfare fusion cell that employs civilian and military experts to more effectively integrate information warfare into all of its operations. This cell will also educate and train our personnel and other leaders to better understand the threat and their role in the information space, including how to integrate offensive and defensive information warfare. Currently, these personnel are fragmented across the staff based on their specialty, tucked away in Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities, basement offices or within a special staff section. Russia has already demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating all elements of information warfare and EUCOM must do the same. Initiatives such as the recent deployment of a U.S. “cyber squad” to Lithuania to defend forward against Russian aggression is a step in the right direction, but still demonstrates the current compartmentalization of cyber operations. Expertise in information warfare cannot exist within a select few offices, hidden behind classification limitations or isolated named operations; all leaders need to gain experience, exposure, and opportunities to better understand information warfare capabilities and how best to integrate them into all operations. A EUCOM information warfare fusion cell would help educate all personnel, government agencies and private business leaders on information warfare.

This recommendation would also build better media and technology literacy across EUCOM’s ranks and throughout its operational environment, which would have an immediate effect against Russian disinformation efforts. Finally, the fusion cell must integrate respected and proven warfighters with operational experience into their ranks. This would ensure its members have a seat at the table, where commanders and senior leaders within the organization espouse their value in front of the entire organization. These efforts will grow information warfare into a more capable, comprehensive and integrated effort against Russian subconventional attacks. Separate, specialized commands and new initiatives such as the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Task Force aim to accomplish many of the same things noted above, but are too compartmentalized and specialized to be fully integrated into the military’s entire operational framework. There are also similar challenges with regard to current classification levels of many of the Army’s current information warfare initiatives. Effective information warfare can no longer be isolated to special operations, its own unique combatant command or compartmentalized programs that require specific clearances to participate. This recommendation would allow EUCOM to develop this capability within its own command structure and more effectively deter Russia’s current disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks. An additional challenge is the U.S. military’s reluctance to lead with information without gaining prior consent through various command channels. This reluctance does not allow our information warfare to move at the speed of relevance, which is the most important requirement within this domain. For this recommendation to be effective, EUCOM leaders must become more comfortable with the potential for operational missteps and be willing to underwrite mistakes in order to give the practitioners the confidence to continue the fight.

EUCOM and its subordinate commands host nearly 30 exercises in a calendar year, focusing primarily on U.S., allied, and partner interoperability. These exercises demonstrate military strength and our commitment to alliances and partnerships, but do little to deter subconventional aggression. This is because the current exercises are focused on lethal operations and do not effectively integrate other government agencies, private industry or nongovernmental organizations to develop and rehearse our own subconventional capabilities outside of the military domain. For the above recommendations to foster subconventional deterrence, they need to be incorporated into an updated and more robust exercise program. Sweden’s Total Defense 2021-2025 plan involves armed forces, government, industry and civil society to build capabilities and partnerships that will ensure Sweden is less vulnerable, more resilient, and capable of learning best practices to defeat conventional and subconventional aggression. EUCOM should incorporate the recommendations from the restructured Russia Strategic Roundtable into its existing exercises and better develop, incorporate and assess our ability to defeat subconventional attacks within an operational exercise framework, as laid out by American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Elisabeth Braw in her article “Countering Aggression in the Gray Zone.” These exercises could also serve as an opportunity to rehearse and evaluate the integration of information warfare into the tactical, operational and strategic levels of military operations. This would provide all participants experience on the effective use of information warfare. Ultimately, exercises such as this would clearly communicate our capability and will to deter and defeat all forms of aggression and improve the societal resilience required to facilitate subconventional aggression. The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine has also driven much of the current discussion on deterrence back into conventional capabilities and military power. This presents a perfect opportunity for the U.S. to gain ground in the subconventional environment and continue to refine our own capabilities. After Russia’s actions in Ukraine are complete, many experts believe it will return to a robust subconventional campaign and will amplify its attacks against the U.S. and its allies as it seeks to rebuild conventional capability. This presents a unique opportunity for the U.S. to improve deterrence against subconventional aggression.

In his proposal for the Hybrid CoE regarding hybrid threats, Keršanskas states that successful deterrence “in the form of a decision not to pursue intended action, is induced in the mind of the hostile actor, meaning both public and private communication plays an important role in shaping the perception.” U.S. President Joe Biden’s recent remarks on our “sacred obligation under Article 5 to defend each and every inch of NATO territory with the full force of our collective power,” coupled with his decision to expeditiously declassify U.S. intelligence regarding Russia’s planned invasion of Ukraine, are examples of effective communication. However, we must do more. We must also communicate tangible resolve and a willingness and capability to implement forceful solutions against all forms of Russian aggression, as detailed by Keir Giles in his 2021 paper for Chatham House. These recommendations will improve subconventional deterrence and can be accomplished within EUCOM’s current organizational structure. By better developing a whole-of-society approach to the Russian threat, integrating information warfare into all aspects of our operations, and effectively exercising our capabilities, we communicate to Russia and other adversaries that the U.S. has the necessary capability and will to deter aggression.

Conclusion

Our nuclear triad, strong alliance system and technologically advanced military continue to deter Russian conventional attacks against the U.S. and NATO allies. However, as NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg recently noted, “… having a strong military is fundamental to our security. But our military cannot be strong if our societies are weak. So, our first line of defense must be strong societies.” By developing a whole-of-society approach where leaders from all sectors within the U.S. work together to better identify, understand and mitigate Russian subconventional aggression, deterrence will be strengthened. The U.S. has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to change strategies with the strategic environment to foster deterrence. These recommended changes continue that tradition and reinforce deterrence so that the U.S. will remain relevant in the 21st century and facilitate international stability for years to come.

Comments are closed.