The strategic importance of raw materials and the case for lithium

By Dr. Ulrich Blum, Menglu Li, Nico Kropp and Karoline Schneeweiss

The supply of raw materials is crucial to the economic success of nations. Given the disparate geographic distribution of resources and localized industrial demand, trade is crucial to balance supply and demand, with global supply and value chains being of strategic interest. Once supply bottlenecks arise, the search for substitutes or recycling resources represents the primary peaceful solution, while economic or military warfare is the conflict-oriented approach. The latter depicts the proximity between trade and war, as emphasized by philosophers, writers and strategists.

However, only few countries have used their bounty of resources to develop into industrial and then post-industrial states. The industrial revolution based on coal and iron ore — developing out of England and sweeping through Western and Central Europe and North America — is a unique example highlighted by economic historians. But they also show that other factors were important, such as trust (for trade) and the presence of regional rivalries to enhance information and military technologies.

Today, many resource-rich countries suffer from a “resource curse,” as their purchasing power derived from the international sale of raw materials exceeds local economic absorption capacity. The result: inflation and/or a revaluation of currencies. This erodes the competitiveness of a country’s industrial base and limits its economic and political development. Russia is a perfect example. The sales of gas, oil, and coal from 2000 onward not only wiped out public debt and allowed Russia to accumulate a huge public trust, but also pushed out many consumer-oriented industries. These achievements made Russia heavily dependent on high-technology inputs, which is now a considerable Achilles’ heel. On the political level, a small elite profited from this development, turning Russia into an autocratic kleptocracy with limited access for its citizens.

Countries rich in raw materials possess strong strategic positions in global trade, but the domestic impacts, both economically and politically, are at least ambiguous. From a new perspective proposed here, Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine can be seen in the context of its diminishing long-term dominance in supplying coal, natural gas and oil, with the depression of oil and gas prices and the international focus on transitioning away from fossil fuels — as initiated by the Kyoto Protocol in the 1990s. Accessing Ukraine’s resources would eliminate competition and strengthen Russia’s market position. A potential economic conflict is being played out militarily. The alternative of Russia conquering Ukraine economically was thwarted by the Orange Revolution in 2004, which was itself a response to the Kremlin’s political and economic aggressiveness.

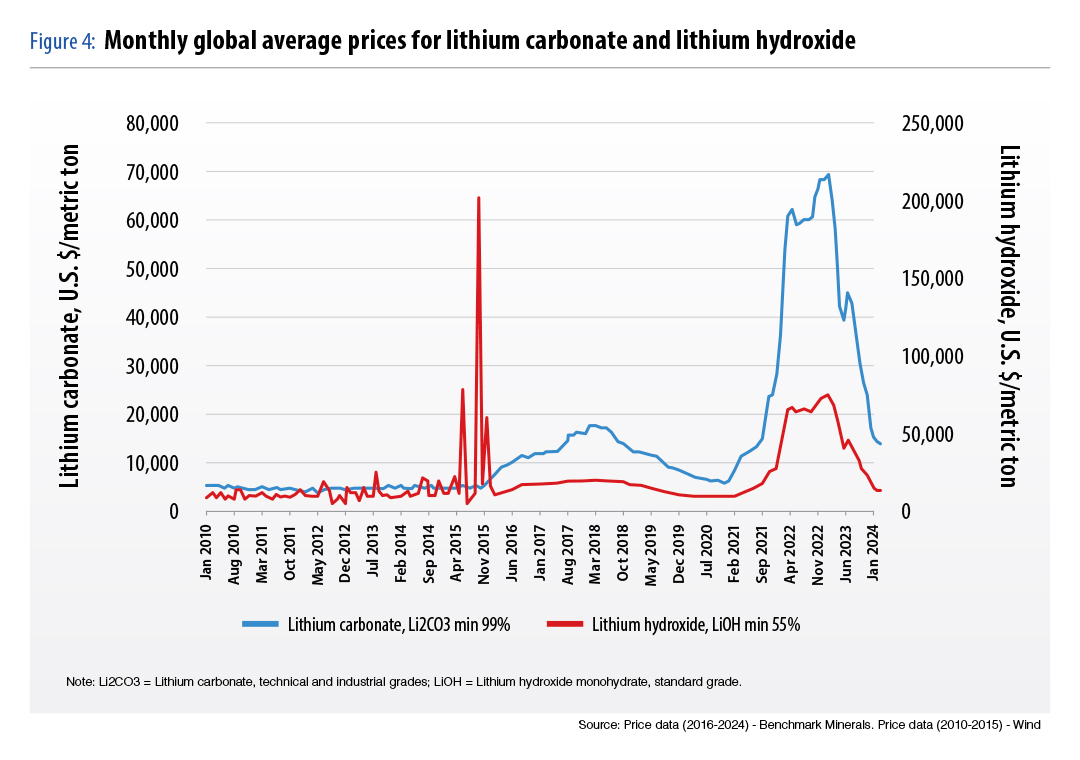

Conversely, China acts in a much more sophisticated way; its dominance in raw materials for energy transition has been evident since the rare earth crisis in the early 2010s, and Beijing attempts to secure its position by taking measures to render investments elsewhere unprofitable. In line with its philosophical tradition, China acts more subtly than Russia, as illustrated by lithium: China has pushed down the price of lithium carbonate by approximately 75% from its peak in 2022-23. This puts at risk numerous investment projects that were intended to reduce Western countries dependence on China-produced lithium.

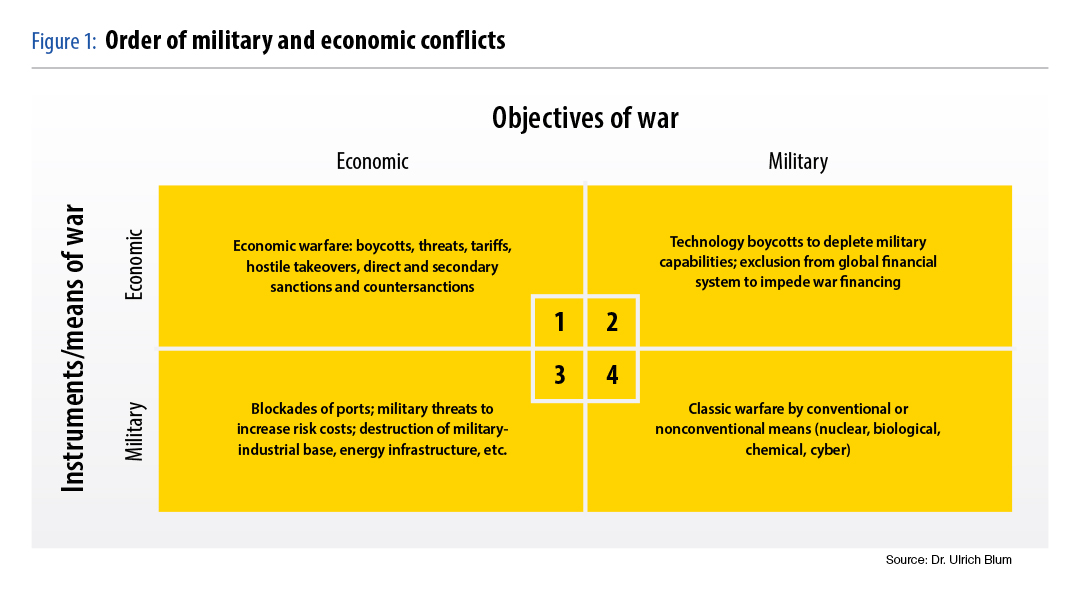

On a more abstract level, economic conflict may oscillate between economic means and, in case of extreme escalation, military action to resolve it. Figure 1 structures the interaction between instruments of war and objectives in two dimensions: military and economic. In the context of the struggle for lithium dominance, this categorization suffices, as we incorporate legal and technological warfare into the economic sphere. From a more general perspective, the conflict matrix could also include other hybrid elements such as migration, information, cognitive and political warfare, and their interaction with the military and economic fields. The table helps to distinguish between the subtle Chinese approach to conflict, found in Field 1, and Russia’s aggressive approach, in Fields 3 and 4. The West’s responses to China are in Field 1, and to Russia in Fields 1 and 2.

Europe’s raw-materials strategy

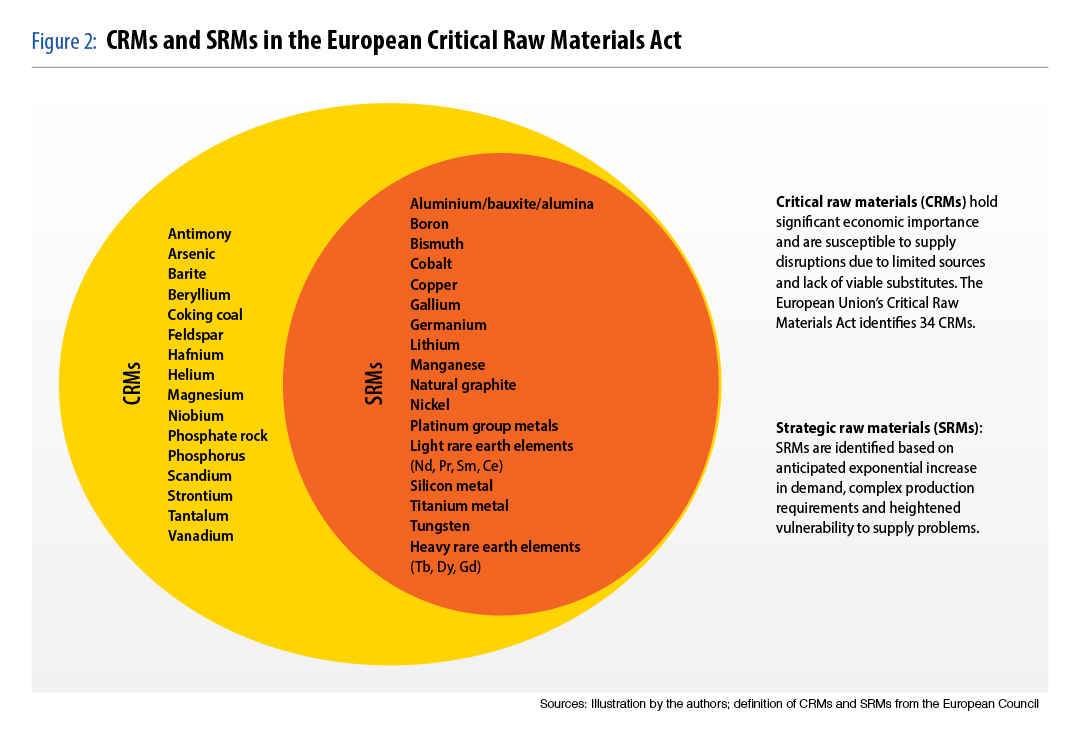

The European Commission aims to make the European Union (EU) more independent in critical and strategic raw-materials from third-country suppliers, thereby enabling the processes of green and digital transformation, securing the aerospace and defense sectors, and enhancing competitiveness. In March 2024, the European Council adopted the European Critical Raw Materials Act. The Act identifies a list of 34 critical raw materials (CRM) and 17 are listed as strategic raw materials (SRM) (Figure 2). To achieve this by 2030, the European Commission set the following goals:

- At least 10% of the EU’s annual consumption should be extracted domestically.

- At least 40% of the EU’s annual consumption should be processed domestically.

- At least 15% of the EU’s annual consumption should be recycled.

- No third country should supply more than 65% of any SRMs.

- Comprehensive explorations are conducted within EU territory.

- Approval procedures are accelerated.

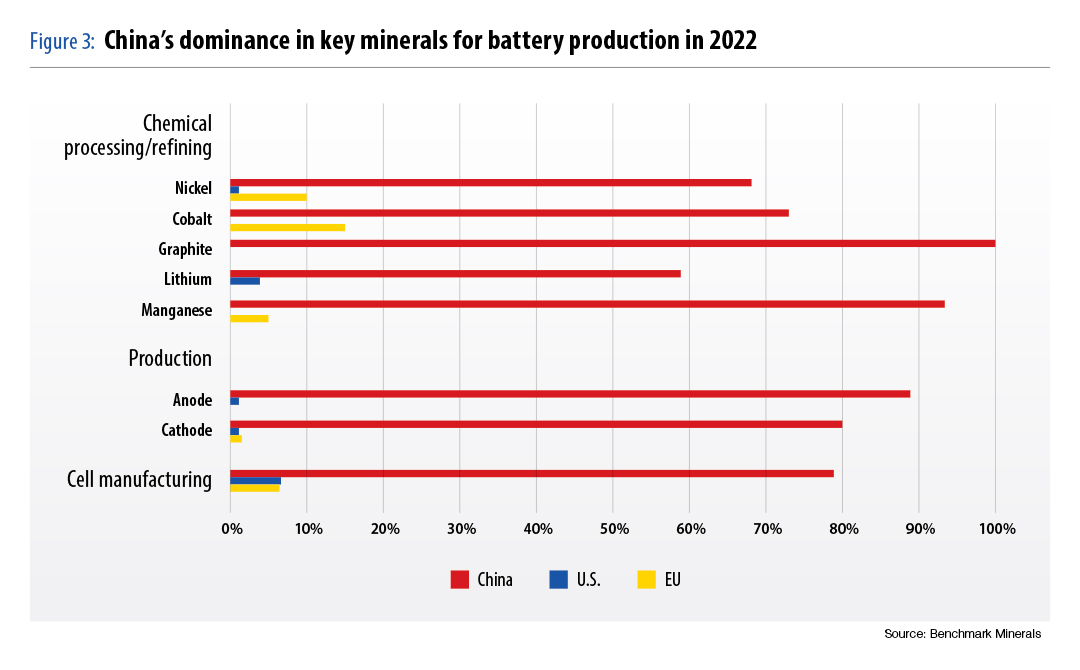

Currently, the majority of the EU’s CRMs and critical processed materials come from non-EU countries, primarily China. The EU is reliant on China, which is also the largest global supplier of CRMs, such as gallium, magnesium and rare earths, according to a 2024 European Council infographic. China also dominates global refining of CRMs. For the lithium-ion battery industry, China accounts for almost 60% of lithium processing capacity, 73% of cobalt capacity, nearly 93% of manganese capacity and 100% of graphite capacity. These statistics belie the fact that most of the world’s lithium, cobalt and manganese are not mined in China (Figure 3). In 2022, China held a significant lead in battery manufacturing, with 77% of global capacity. Six of the world’s 10 largest battery manufacturers are Chinese. This dominance is supported by its vertical integration in the battery value chain and large electric vehicle (EV) market, but also attributed in part to policy decisions and subsidies implemented by the Chinese government. With regulations that effectively restricted foreign battery producers’ access to subsidies from 2015 to 2019, they faced challenges in accessing subsidies and participating in China’s rapidly growing EV market while domestic producers expanded rapidly and invested in the value chain from mining to EV production.

Lithium as an economic weapon

Lithium prices plummeted 82% from a peak of about 66,000 euros per metric ton in January 2023 to approximately 12,503 euros per metric ton in February 2024. Many investment plans for exploring new lithium sources, and especially for construction of the corresponding processing facilities, have been put on hold. Investors are questioning whether classical market and competitive forces are at play or whether state intervention by China is driving this development. Figure 4 illustrates that the prices of lithium hydroxide are significantly more volatile than those of lithium carbonate. The former is much more sensitive to storage and transportation, as it readily reacts with carbon dioxide to form lithium carbonate, which is typically produced as the first processing stage before purification into battery-grade material.

A case of déjà vu for lithium?

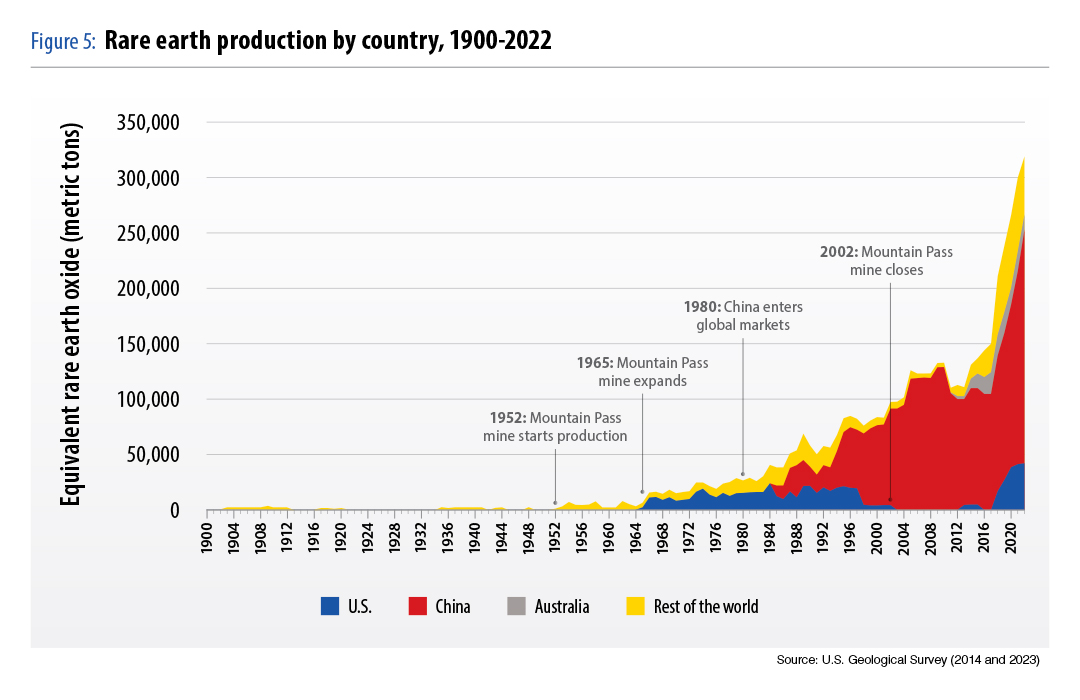

Current developments in the lithium market reveal significant parallels to the rare earth crisis. Since the 1960s, rare earth applications gradually expanded to the petroleum industry, computer systems and consumer goods, such as television screens. Because of increased demand, the Mountain Pass Mine in the state of California in the United States was expanded in 1965 and then provided over half of the world’s rare earth elements (REE). Until the 1980s, the U.S. dominated most REEs globally, with over 60% of world output (Figure 5). At that time, the U.S. was the only country to cover the entire value chain, from producing rare earth ores to downstream products such as magnets.

However, from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, the U.S. lost its dominant market share to China. During this period, China produced and provided a large amount of rare earth products at low cost and quickly surpassed the U.S. in production and export. On the one hand, China possessed approximately 34% of the world’s reserves. It has the largest bastnaesite deposit, the Bayan-Obo Mine in Inner Mongolia, accounting for more than 83% of the country’s total rare earth reserves and approximately 38% of global reserves. Of heavy rare earths, 95% are supplied by mines in South China. On the other hand, the Chinese government under Deng Xiaoping underscored the importance of the rare earth industry to China’s national strategy: “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” With government support, coupled with technological breakthroughs in refining, low labor costs and few environmental constraints, China forced other suppliers out of the market and became the dominant global producer. The Mountain Pass Mine was closed in 2002 because of a toxic waste spill and was not reopened because of the competition from Chinese suppliers until 2012. It resumed operations in response to China’s scarcity strategy — such as sharply decreased export quotas — aimed at further increases to value-added production stages, particularly in E-mobility and green energy.

From the 1980s to the 2000s, Western countries stood by as China invested more in both upstream and downstream research, and also implemented restrictions on production and exports, such as quotas and taxes to reduce the raw materials cost to downstream domestic companies and support innovation such as the high-performance magnets crucial for energy transition. Furthermore, these restrictions appear to have incentivized a strong dependency by foreign firms on Chinese REEs, inducing them to move production to China and share their advanced technologies, which expanded the depth of the domestic value chain and product-life length.

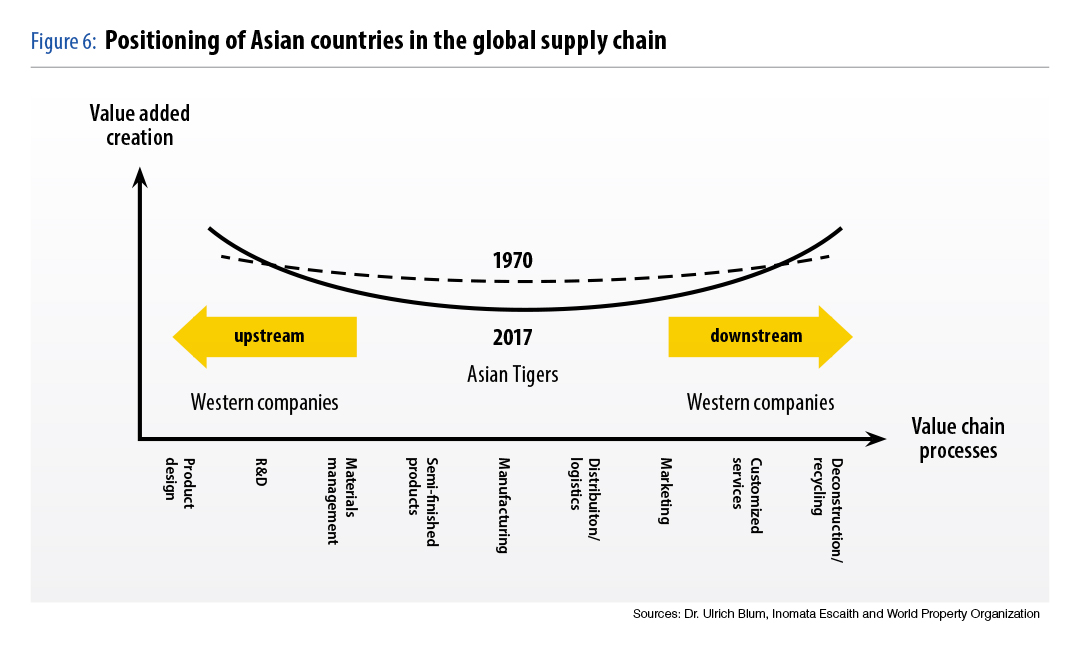

The economic policy background is founded in a smile curve, which illustrates that Western companies dominate the value-added production stages, while Asian companies primarily function as an extended workshop (Figure 6). Through “education tariffs” and subsidies, China aims to develop its technology and value-added products. However, the price for rare earths was such that, from the mid-2010s onwards, many countries aggressively sought alternatives — mines, sources of semifinished products, substitutes and recycling methods — breaking the Chinese monopoly. Nevertheless, Western countries only played supporting roles and used market-driven solutions to let companies ensure their own supply chains. China retains a strong market position and an advanced industry prepared for the climate change transition.

Solar industry and electric mobility

From the perspective of market-oriented, liberal countries, state-capitalist systems such as China’s pose an economic challenge. They can not only hinder imports and subsidize exports, they can also, in a more covert manner, promote and boost domestic industry sectors against competing foreign firms. This was indeed the case with the solar and electric transportation industries: In both cases, the Chinese government heavily subsidized the establishment, growth, and associated technological research and development, resulting in two sectors with massive overcapacity, enabling them to compete internationally for market share with aggressive pricing — thereby eliminating foreign industries such as the German solar sector that pioneered development in the 2000s. However, “dumping” in the classical sense is no longer applicable, as price competition is intense even within China and bankruptcies or market exits are part of this new normalcy. From the West’s perspective, the Chinese export drive is ambiguous: It drives Western companies out of their home markets, but the low prices ease the green energy transition. This is also happening with the electric car market.

Assessing China’s actions

Since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), China has continuously used a variation of measures that have tested the limits of the WTO legal system. For example, China implemented export restraints for selected inputs to favor domestic producers, or even to force international producers into technology transfer and investment in the Chinese-made inputs. Generally, export restrictions are prohibited under WTO law. However, the application of export restrictions can be justified if the prohibition does not extend to situations where they are, according to GATT Article XI, “temporarily applied to prevent or relieve critical shortages of […] products essential to the exporting contracting party.”

China implemented export restrictions on raw materials and rare earth elements that lead to an increase of world prices because of China’s almost monopolistic position. This price development on the world market gave Chinese companies a competitive advantage, as it lowered prices in the domestic market. Hence, China’s downstream industry was able to use cheaper inputs for domestic production, facilitating the establishment of a domestic value chain.

As a reaction to those measures, a series of WTO cases followed. The first case, China – Raw Materials was jointly brought by the EU, Mexico and the U.S. in 2009, with a final ruling in 2012. China lost and had to abolish the violating measures. The second case, China – Rare Earth, focused on export restrictions on rare earth elements. This time it was brought by the U.S, the EU and Japan in 2012, with a decision in 2014. Again, China lost and had to remove the challenged export restrictions.

The WTO legal system was used successfully and effectively by the complaining states. It offered them a forum to solve disputes and eliminate illegal trading measures. But China still benefitted economically long term from the illegal measures, though they were only in effect temporarily. It built a strong industrial base while moving up the value chain. Therefore, the cases must be seen in a bigger picture: The use of export restrictions violated WTO law, but still helped China reach its goal of building its own high-tech industries. This highlights an important gap in the WTO system. Although the breaching party must bring its actions in line with WTO law, the system focuses on conforming trading actions within legal obligations rather than providing remedies to offset the economic harm caused by violations. Additionally, litigation requires at least three years, which gives the lawbreaking state time to reap the benefits of its illegal trade measures. By exploiting this gap, China tested the limits of the WTO; it was willing to lose WTO cases and even suffer reputational harm so long as it achieved more important economic goals.

The West should have, by then, been aware that China makes creative use of WTO rules. However, in using the stratagem “Hit the grass and startle the snake,” it realized that the West remained passive — the snake did not startle and became aware of a long-term threat.

The use of strategic competition theory

Competition consists of two subprocesses: innovation, defined as “the introduction of new combinations,” which can manifest in products, processes, input and output markets, as well as in the institutional organization of firms and markets; and the transfer of market share from “laggards” to entrepreneurs. The intensity of competition is then measured by the speed at which first-mover advantages erode due to imitators. State industrial policy is particularly successful when it can absorb global knowledge and localize it in production techniques. However, there is a limit: the absorption capacity of new knowledge, i.e., the ability to properly assimilate discoveries and inventions, is a function of one’s own research, and often international division of labor in research. In this aspect, China’s international participation is exceptionally high.

One of the innovative achievements of the Chinese economy undoubtedly includes the plurality of market entries, with lithium and battery production at the forefront. These technological and digital revolutions have brought forth two additional competitors in car industries: battery manufacturers (e.g., BYD) and digital conglomerates (e.g., Xiaomi), alongside traditional automotive producers.

Lithium is central to securing market position. What are the strategies? The following are particularly noteworthy for maintaining China’s existing lithium dominance, positioning itself as an industrial leader capable of determining the length of the product life cycle:

- Strategic promotion of research and development, especially in the lithium industry, and extensive coordination on export prices.

- Willingness to invest globally in lithium extraction, regardless of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria, to secure reserves and drive-up prices for third parties in the long term. In competition theory, this is referred to as “raising rivals’ costs” by shielding procurement markets from competitors at the same value-chain level.

- Setting limit prices, i.e., the highest possible price that is still low enough to deter market entry by potential competitors. Established Chinese firms can absorb short-term losses to maintain market share and dissuade new competitors. This parallels the China’s rare earth industry strategy.

- Openness to market entry and competition in the downstream sector, especially in the electric automotive industry in China.

To sum up, competition in the rare earth sector, enforced through price reductions, is intended to build or stabilize downstream value chains and force competitors out of the market or prevent them from entering. When price increases in the sector had to be reversed after WTO arbitration, the global division of labor in strategically important areas, such as high-performance magnets, had already shifted in China’s favor. The case of lithium is different: The driving force is not price manipulation but competition among Chinese provinces to attract high-technology employment and firms. It was incentivized with subsidies (e.g., R&D, capital costs, preparation of location, access to infrastructure) and has created overcapacities in many industries. The erosion of prices has dramatically increased competition intensity, leading to increased innovation, especially in production processes, lower prices and the elimination of inefficient companies.

The Russian approach

The Paris climate accord and, prior, the Kyoto Protocol — aiming for the long-term decarbonization of the global economy — were severe blows to the business model of the Russian Federation, which had experienced the consequences of depressed oil prices from the 1980s to the 2000s. Reduced energy revenues helped bankrupt the Soviet Union and, along with other crises, led to its collapse. Perhaps it was inevitable for Russia to expect negative outcomes. The Kremlin tried to bind Ukraine’s economy, which was suffering from transformation problems such as unraveling supply chains and lost markets, by threatening to withdraw credit. This put a strain on Ukrainian efforts to reorient toward Europe. In a certain sense, it was strategically logical for Moscow to try to expand its control over Ukraine’s resources and develop monopolistic power — at least on the European continent. Conversely, easier European access to Ukrainian resources would have amounted to a further erosion of Russia’s economic base.

Ukraine’s resource competition

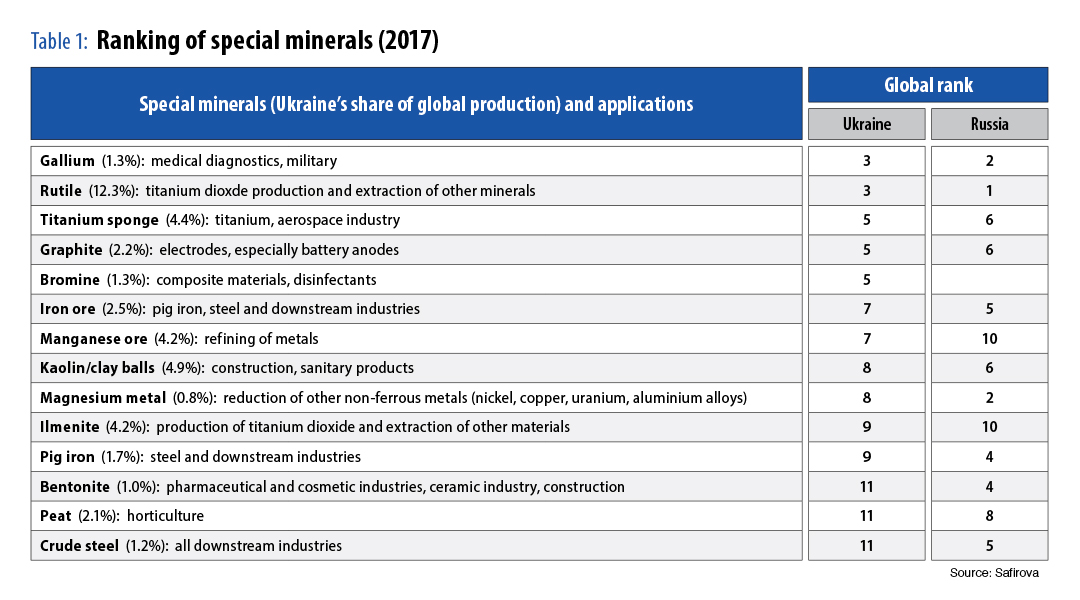

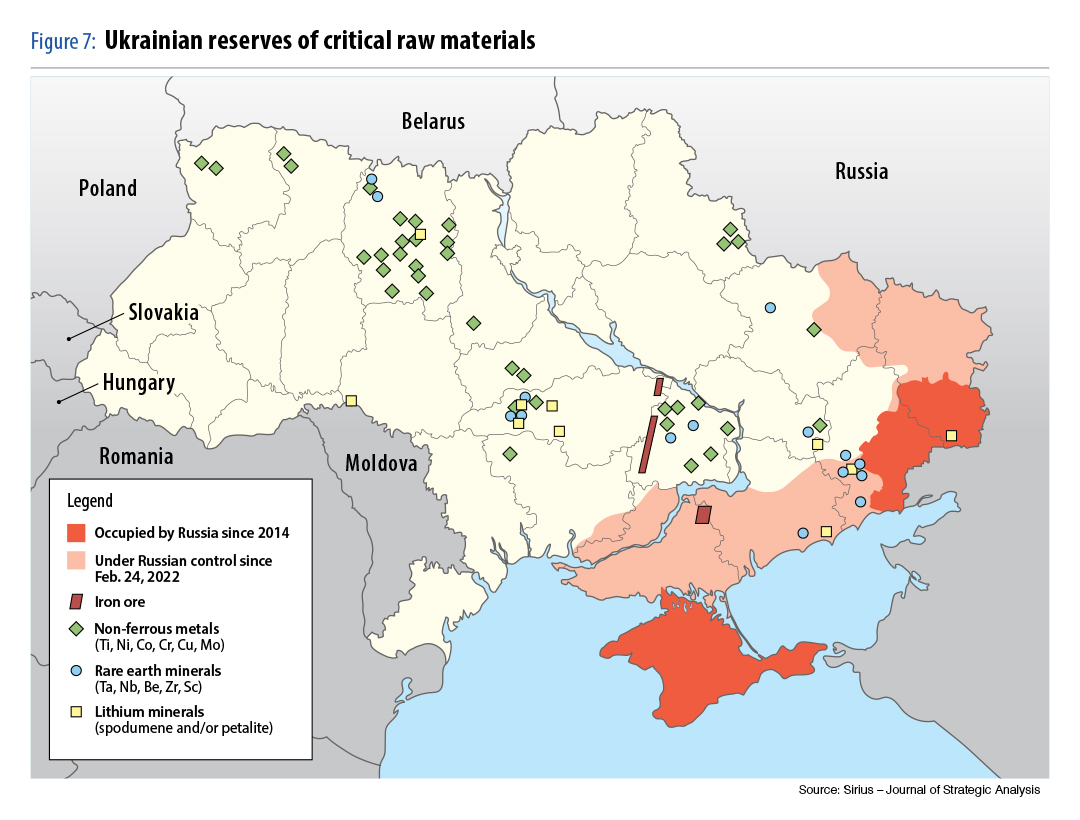

Table 1 below illustrates the competition for raw materials between Russia and Ukraine. Magnesium, which was mentioned in Figure 2 because of China’s high processing capacities, plays an important role in lithium extraction, as does graphite.

Lithium deposits in Ukraine

Ukraine’s lithium deposits are found in pegmatitic deposits that also contain other elements, such as niobium, tantalum, rubidium and cesium, in addition to the classic industrial minerals such as feldspar and quartz. As shown in Figure 7, at least two of the known lithium deposits (Kruta Balka in Zaporizhzhia Oblast and Shevchenko in Donetsk Oblast) are in Russian-occupied territory in eastern Ukraine. Other battery raw materials include graphite, copper, nickel and cobalt. However, it should be noted that lithium deposits in Ukraine are underexplored by international standards and entire value chains need to be established.

The spatial distribution of mineral resources results in an important geostrategic and economic consequence: A large part of these mineral resources, especially coal and gas, as well as large proportions of metallic raw materials, are located in areas that are currently occupied by Russia, or are dangerously close to the current front line. If this becomes a ceasefire line, no sensible non-Russian investor will risk investing in these areas, on either side of a putative demarcation line. This assessment is shared by the Canadian foundation SecDev. Additionally, it is in Russia’s interest to secure the crucial areas of eastern Ukraine that host significant amounts of the country’s coal, gas and oil reserves, in order to secure its own dominance of these energy resources. Even if the development of alternative energy sources leads to a transition from fossil fuels, oil and gas will remain essential energy sources and the basis for many fuels and petrochemical products. This could be an incentive for Russia to wage war permanently, starve Ukraine economically, and inflict massive economic damage on Europe.

Lessons for the West

Lithium and other critical resources are keys to the West’s successful energy transition. The West is squeezed between China’s limit-price strategies that prevent profit-sustainable market entries and the inability to access the long-term and industry-stabilizing resources of Ukraine. Even if substitutes can be found — for instance sodium, which would imply more weight and less distance in case of electric cars — the availability of lithium will remain an important geopolitical and economic issue for many applications.

And China’s resource squeeze is more comprehensive. As observed recently, the limit-price strategies of China are also visible with nickel, cobalt and graphite. For instance, China bought the vast deposits of Canadian neo-lithium in Argentina in 2021, as part of its grand strategy to secure global deposits. In another case, Glencore Canada closed its nickel mine in New Caledonia in 2024 because of fierce Chinese price competition. At this limit, the West is crunched between the high costs of economic war with China and the high costs of military war with Russia.

This necessitates strategic decisions. Ukraine and its deposits of critical minerals such as lithium must be secured as they are scarcely available in Western and Central Europe. The gain in strategic autonomy and the reduction of risk costs should outweigh any initial investment. This is a military task. But it would require supporting Ukraine to regain its sovereign territorial integrity from before 2014. The alternative costs are worse: a collapse of the European security architecture, mass migration and ongoing supply-chain risks for critical materials. New clusters could become the basis of stable and sustainable energy transition and would resolve two key problems, especially for the EU: It would finance Ukrainian reconstruction and allow for decoupling from China’s near-monopolistic control of critical mineral resources. In the latter case, this would put the West on more equal terms with China. In terms of conflict reduction, a more globally balanced landscape of critical resources would reduce the temptation to undermine the international order. Again, a price is to be paid — energy transition in the West would become more expensive. But the costs of an erosion of strategic industries could be much higher.

Comments are closed.