How the Kremlin employs narratives to destabilize the Baltic states

By Capt. Brian P. Cotter, U.S. Army

The Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula grabbed headlines in March 2014, just a short time after Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was ousted from power. Protests began in November 2013 when Yanukovych backed out of an economic pact with the European Union at the behest of Russian President Vladimir Putin and signed a separate deal that more closely aligned Ukraine with Russia. The overthrow of Yanukovych, a Kremlin ally, and the events that followed — beginning with the annexation of Crimea and the violent birth of self-declared, pro-Russian autonomous republics in Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine — illustrated the stark divide between ethnic Ukrainians in the country’s west and those in the east who identified more strongly as Russian.

Since the seizure of Crimea, Russia has remained active in eastern Ukraine, where its military involvement has been both covert and, in spite of repeated denials, overt, as attested to by U.S. Army Europe Commander Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, in March 2015, when he estimated Russia had around 12,000 troops operating in Ukraine. While Russia’s support to the Ukrainian rebels has predominantly been in armaments and provisions, the implementation of its own, state-controlled Russian-language media has been used to great effect in the battle for public opinion throughout the wider Russian-speaking world. Putin has leveraged the fact that most Russian-language media available throughout the world is broadcast or rebroadcast directly from Russia, where the Kremlin maintains a tight grip on the media. This has created a series of exclusive narratives, carefully crafted to influence specific population groups, including those beyond the borders of Russia and eastern Ukraine.

Russia’s divisive media campaign and the efficacy of its narratives on targeted groups has exposed an alarming fault line along the eastern seams of Euro-Atlantic institutions. While Ukraine has generated headlines, in northeastern Europe, the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — members of NATO and home to significant Russian minorities — represent a strategic vulnerability to the Euro-Atlantic order. One Russian political analyst, Andrei Piontkovsky, observed that Putin’s ultimate desired end state is “the maximum extension of the Russian World, the destruction of NATO, and the discrediting and humiliation of the U.S. as the guarantor of the security of the West.” Large ethnic Russian populations in the Baltic region present an opportunity for the Kremlin to cultivate pro-Russian fervor and discredit the West by leveraging carefully conceived narratives to influence and potentially destabilize these three NATO members — and the alliance as a whole — from within.

The Gerasimov Doctrine

In August 2008, Russia engaged in a brief conflict with the Republic of Georgia over the status of the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Although Russia ultimately prevailed, the war “revealed large-scale Russian military operational failures,” Russia expert Jim Nichol noted. This triggered a period of self-evaluation that resulted in two developments: a renewed push to modernize and reform Russia’s conventional military forces and a re-evaluation of how Russia would wage wars in the future, Nichol said in his Congressional Research Service paper, “Russian Military Reform and Defense Policy.”

Enter Gen. Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of the Russian Armed Forces. In 2013, he published an article in the relatively obscure Russian periodical The Military-Industrial Courier that introduced a new approach to waging war, a strategy that has come to be known as hybrid warfare. The shift to a hybrid, nonlinear warfighting strategy represents at least a tacit acknowledgement that Russia’s conventional forces suffered a capabilities gap and that alternative methods of circumventing an enemy’s conventional superiority were necessary. In his article — translated and published by Robert Coalson of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — Gerasimov recognized that the exploitation of the information sphere could allow Russia to overcome its limited conventional capabilities.

The Gerasimov Doctrine emphasizes that “the role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness.” Coupled with the careful employment of small-scale military operations and the influencing of multiple political, economic, social and cyber levers, dominance of information can dramatically alter the battlefield without ever creating the impression that there is a battlefield in the first place.

The Russkiy Mir

The current state of Russian geo-political thought approximates similar ideologies in modern history. Throughout the early- and mid-20th century, the concept of pan-Arabism permeated the greater Middle East. The movement sprung from the belief that people belonged together as a community, bound by linguistic, cultural and religious ties. No longer under domination by the Ottoman Turks, many Arabs believed their future was inexorably tied to one another; a unified pan-Arab world would fill the void left as Ottoman rule faded into history. Early incarnations of pan-Arabism were ultimately “short-lived as political considerations overrode ideological consistency,” Christian Porth noted in Al-Jazeera, but the notion that a people bound by a common culture, language, religion or ethnicity can and should gravitate toward one another is neither unique nor extinct.

Twenty-first century Russians, like the Arabs in the first half of the previous century, are emerging from a period of empire, a period during which, for better or worse, the so-called Russkiy Mir, the Russian world or community, grew considerably. Russkiy Mir implies that national borders are viewed as secondary to ethno-linguistic ties; at its core, it describes Russia not as a country, but as a people. In his article for The Daily Caller, Ukrainian human rights activist Volodymyr Volkov explains it this way:

In [the] Russian language this term is used as “Russkiy” world. This is significant because the name of [the] country is “Rossiya”; thus, Russians, by citizenship, are called “Rossiyane,” while Russians by ethnicity are called “Russkiye.” The concept of the “Russkiy mir,” or the Russian world, is an ethnic-centered concept.

Today, the notion of the Russkiy Mir has been revived by Putin in developing his policies toward countries of the former Soviet Union, many of which host sizable Russian-speaking minorities. In a July 2014 speech to the Russian parliament, Putin remarked: “When I speak of Russians and Russian-speaking citizens, I am referring to those people who consider themselves part of the broad Russian community. They may not necessarily be ethnic Russians, but they consider themselves Russian people.” Further supporting this thought, Max Fisher notes, in an article for the online news outlet Vox, that the ethno-linguistic boundaries of the Russkiy Mir conveniently align with the Kremlin’s perceived geo-political sphere of influence.

Russia, NATO and the Baltics

Prominent among the narratives the Kremlin has built within its version of the Russkiy Mir is the assailing of Western institutions, the most conspicuous of which has been NATO. Indeed, in a late 2014 revision to its military doctrine, Moscow labeled NATO as Russia’s primary threat. NATO and its eastward expansion have long been a key source of Russian discontent, and it has now manifested itself as one of the central narratives in its information campaign, though NATO categorically denies the Kremlin’s contention that, in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, alliance leaders promised there would be no eastward expansion.

Regardless of whether it’s justified or not, Joshua Shifrinson of Texas A&M University told the Los Angeles Times, Putin genuinely feels that Russia has been done wrong by the West. Putin’s convictions create a volatile friction point when considering the Baltic states, the former Soviet republics-turned-NATO members nestled along Russia’s northwestern border. Though Article 5 of NATO’s charter guarantees mutual, collective defense, rendering it unlikely that Russia would ever conduct any overtly hostile acts against a member state, particularly of the first-strike variety, to Putin, the Baltics still embody a perceived Western encroachment on Russia’s traditional sphere of influence.

Russian State Media

Freedom of the press in Russia has been gradually rolled back since Putin became president on New Year’s Eve 1999. In April 2001, the Kremlin took over NTV, taking “Russia’s only independent national television network off the air after months of denying it planned to do any such thing, ” noted Steven Baker and Susan Glasser in Kremlin Rising: Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the End of Revolution. “NTV had proven to be a choice target, the most potent political instrument in the country not already in state hands.” Thus began the assault on independent media in Russia.

The pattern has only continued and worsened. Mass media, which is largely state-owned or state-controlled, is the primary vehicle through which Russia disseminates its messaging. Former CNN contributor Jill Dougherty said in The Atlantic that “as a former KGB officer and head of the KGB’s successor agency, the FSB, Putin knows the value of information.” She concludes that “for him, it’s a simple transactional equation: Whoever owns the media controls what it says.” This is predicated on control of the television networks. In fact, data from the Levada Center, an independent Russian research organization, indicate that 90 percent of Russians are television news watchers.

Not surprisingly, the government in Moscow now controls the majority of television and print media in the country. Freedom House, an independent human rights watchdog organization, evaluated Russia’s press status as “not free” in 2014, citing a “vast, state-owned media empire” and the consolidation of several national media outlets into one large, state-run organization, Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today):

The state owns, either directly or through proxies, all five of the major national television networks, as well as national radio networks, important national newspapers, and national news agencies. … The state also controls more than 60 percent of the country’s estimated 45,000 regional and local newspapers and periodicals. State-run television is the main news source for most Russians and generally serves as a propaganda tool of the government.

Coupled with continued harassment of journalists and the use of intimidation or violence against reporters delving into sensitive topics, the overall climate — and forecast — of media freedom in Putin’s Russia is grim.

The reduction of free and independent media in Russia has allowed the Kremlin to dictate and disseminate its own narrative. This permits Putin to maintain an advantage over political opponents and emerge from crises unscathed by domestic and international public opinion. Indeed, Levada Center polling shows Putin’s approval ratings soared after the start of the crisis in Ukraine and standoff with the West, reaching 87 percent by July 2015, even as the Russian ruble faltered under the weight of sanctions and falling oil prices.

Downplaying the effects of sanctions on the economy, the Russian media routinely points a finger at the EU, NATO and the U.S., drumming up support for the Kremlin as it nobly defends the Otechestvo, or fatherland, against an alleged coordinated Western conspiracy to stymie the re-emergence of a powerful Russia. Any Western accusation against Russian actions is quickly met with a response from the state-controlled media, calling into question even easily proven empirical data and simply writing off anything anti-Russian as farcical and based on dubious information sourced from Western conspirators.

The goal is to discredit Russia’s enemies through disinformation, described by Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev in an article for online journal The Interpreter as “Soviet-era ‘whataboutism’ and Chekist ‘active measures’ updated with a wised-up, postmodern smirk that insists everything is a sham.” They further elaborate on how “the Kremlin exploits the idea of freedom of information to inject disinformation into society. The effect is not to persuade or earn credibility, but to sow confusion via conspiracy theories and proliferate falsehoods.”

Essentially, the Kremlin policy is to discredit everyone and everything and, in so doing, create a climate of doubt in which it is nearly impossible to believe anything at all. Weiss and Pomerantsev remark how “the Kremlin successfully erodes the integrity of investigative and political journalism, producing a lack of faith in traditional media.” By accusing Western media — or even the last vestiges of independent media within Russia — of acting in the very manner in which the Kremlin-controlled media behaves, then no one can be trusted. This has proven effective, especially among native Russian speakers. In Estonia, for example, numbers show that in the event of conflicting reports, only 6 percent of the ethnic Russian population “would side with Estonian media accounts,” according to a study by Estonian Public Broadcasting.

Complicating matters is that a significant portion of the Russian-speaking Baltic population receive their international and regional news through the Russian media, according to a paper from the Latvian Centre for East European Policy Studies. Indeed, a report by Jill Dougherty for Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center confirms that “in countries that were once part of the Soviet Union, where many ethnic Russians reside and the Russian language is still spoken, Russian state media penetration has been effective.” Additionally, The Associated Press noted in 2014 that though much of Russian-language media consumed in the Baltics is produced from within Russia itself, even the First Baltic Channel (PBK), a Riga, Latvia-based Russian-language channel with an estimated 4 million viewers across the region, has come under suspicion of being yet another Kremlin mouthpiece. In fact, the Lithuanian State Security Department described PBK as “one of Russia’s instruments of influence and implementation of informational and ideological policy goals” in a 2014 Baltic News Service report.

Moscow has exploited its nearly exclusive control over Russian-language information, investing heavily in its state-run media apparatus, including a 2015 budget of “15.38 billion rubles ($245 million) for its Russia Today television channel and 6.48 billion rubles ($103 million) for Rossiya Segodnya, the state news agency that includes Sputnik News,” the Guardian said. By saturating a market already devoid of moderate independent Russian-language media outlets with Kremlin-orchestrated information, Putin is able to expand the reach of his message throughout the Russkiy Mir with virtual impunity.

The Guardian further suggests that it is in the Baltic arm of the Russkiy Mir, along NATO’s Russian-speaking fringe, that the populations are particularly susceptible to exploitation by the Kremlin information campaign:

Concerns about the aims of expanding Kremlin-backed media outlets are especially palpable in Russia’s EU member neighbours, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which all have significant Russian-speaking minorities. … In such a sensitive political climate, there are concerns that Kremlin media outlets could spark tensions between ethnic Russians and national majorities.

This area, where attitudes are being molded to view the West as anything from suspicious to hostile, represents a significant vulnerability to the national governments in the Baltic states as well as NATO.

The Russian Minority in the Baltics

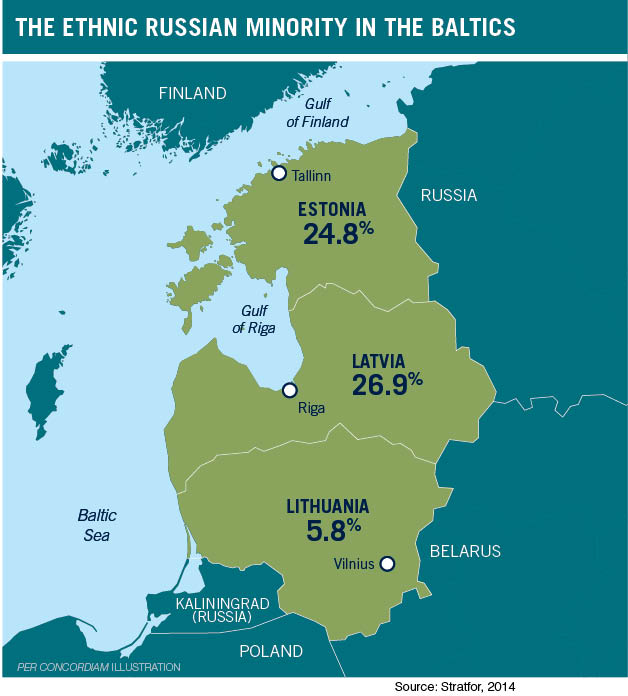

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia each boast a sizable Russian minority. Russians account for roughly a quarter of the populations of Estonia and Latvia and 5.8 percent of Lithuania’s. The percentage of people who speak the Russian language in these countries is even higher.

Complicating matters is the history of the Baltics from 1939 until the collapse of the Soviet Union. The 1939 nonaggression pact, the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, between Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany, partitioned Europe and would later be used to justify the Soviet annexation of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. As Orlando Figes notes in his book, Revolutionary Russia: 1891-1991: A History, after World War II, “in the Baltic lands and west Ukraine, there were mass deportations of the population — the start of a broad campaign of what today would be called ethnic cleansing — to make room for mainly Russian but also east Ukrainian immigrants.”

Thus, when the Soviet Union collapsed, there were significant Russian populations remaining in the Baltics. In Estonia and Latvia, laws were introduced after independence in 1991 that effectively rendered their Russian populations as stateless, euphemistically referring to them as “noncitizens.” While they have made it possible for these people to naturalize, Estonia and Latvia, in their respective citizenship or naturalization acts, require Russians to prove proficiency in the Estonian or Latvian languages and to pass exams in civics and national history. In Latvia, where, according to an August 2014 article in The New York Times, “many of these Russian speakers have been in limbo, as noncitizens squeezed out of political life, largely unable to vote, hold office or even serve in the fire brigade,” the language requirement extends beyond a mere citizenship requirement, permeating many sectors of everyday life. In Estonia, by law, the requirements are similar. On the other hand, in Lithuania, all people living within its borders received citizenship on independence.

Ultimately, divisions continue to exist between the Baltic majorities and ethnic Russian minorities. So the climate is ripe for Russian exploitation and an opportunity to weaken the strength of the state and, consequently, impact NATO unity from within. Indeed, U.S. Air Force Gen. Philip Breedlove, the top military commander in NATO, noted that at the onset of the crisis in Ukraine, the Russians executed perhaps “the most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg we have ever seen in the history of information warfare.”

A Hybrid Assault

Building upon the Russkiy Mir narrative, the Kremlin has favored a multilayered approach to its information campaign in the Baltics: Delegitimize NATO and its affiliates — rebranding its own concerns about the alliance as a threat to order and peace in Europe — and assail Baltic membership in the organization, suggesting they are unwitting pawns in a conspiratorial anti-Russian plot. The intent, by design, is to drive a wedge between those in the region who seek greater Western integration and those, who as members of the wider Russkiy Mir, consider Western attitudes and actions toward Russia as adversarial to them as well.

Andrei Baikov, a Russian commentator at Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper sums up Russian attitudes this way: “NATO and European peace are incompatible.” Other sources have been less subtle in describing the perceived threat from the Euro-Atlantic alliance, such as the radio network Voice of Russia (recently rebranded as Sputnik News and, as mentioned previously, owned and operated by the state-owned Russia Today conglomerate), which proclaimed it was a U.S.-led, NATO-sponsored coup that led to the toppling of the Yanukovych regime in Ukraine.

Andrei Baikov, a Russian commentator at Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper sums up Russian attitudes this way: “NATO and European peace are incompatible.” Other sources have been less subtle in describing the perceived threat from the Euro-Atlantic alliance, such as the radio network Voice of Russia (recently rebranded as Sputnik News and, as mentioned previously, owned and operated by the state-owned Russia Today conglomerate), which proclaimed it was a U.S.-led, NATO-sponsored coup that led to the toppling of the Yanukovych regime in Ukraine.

The notion of the U.S. as the overlord of NATO is another recurring theme. Headlines such as “The USA Wants to Dismember Russia,” in Moskovskaya Pravda, indicate how the Kremlin seeks to portray the U.S. One article published in Krasnaya Zvezda, or Red Star, an official publication of the Russian Defense Ministry, stated that NATO’s eastward expansion was fueled by a genuine anti-Russian campaign within the alliance, that the Baltic states were forced into the alliance and that NATO considers the Russian Federation as a “new evil empire that, along with the extremist IS [Islamic State], should be removed from history.” This essentially sums up the Kremlin message as it relates to NATO: The alliance seeks to surround, destabilize and ultimately destroy Russia.

Impact on NATO

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its subsequent support to separatists in eastern Ukraine, the West imposed sanctions that have contributed to a downturn of the Russian economy and largely isolated it on the international stage. However, a number of NATO allies were hesitant to become involved militarily in Ukraine — a country to which the alliance has no formal obligations — at the risk of provoking Russia, which was among Europe’s primary suppliers of energy and still possessed formidable military assets. Disagreement within the alliance on how to confront Russian revanchism has led some to postulate that Russian aggression, particularly that which employs hybrid tactics, could threaten the cohesion of NATO. The fear is that the employment of hybrid tactics may not be enough to build the consensus necessary to invoke Article 5, especially considering the lack of popular support in many key NATO members. A recent Pew Research poll found that the public in many key NATO states would be reluctant to provide military aid to a fellow NATO member in need, prompting Vox columnist Max Fisher to remark: “If it were up to German voters — and to at least some extent, it is — NATO would effectively surrender the Baltics to Russia in a conflict.”

Yet it remains doubtful that Putin would ever fully succeed in dislodging the Baltic region from NATO and re-establishing Russian hegemony. Even if NATO were unable to mobilize collectively, there would likely be a unilateral response from the U.S., which has publicly declared its commitment to defend its Baltic allies. However, the Kremlin can use softer, hybrid techniques to influence conditions within the region, such as investment in pro-Russian political parties in the Baltic states and, of course, a robust information campaign. In wielding its narratives to build pro-Russian and anti-Western sentiments, Moscow can weaken NATO institutionally and relegate the Baltic states to pariah members without risking potentially harmful provocations.

Conclusion

Baltic residents who speak Russian at home are most susceptible to the Kremlin’s narratives. Countering Russian disinformation will be critical in the battle for public opinion in the Baltic states as Russia poses as both a protector of ethnic Russians and a counterweight to NATO. Failure to respond to the Russian information campaign leaves those sizable Russian minorities open for exploitation by the Kremlin.

Responding to Russia cannot be a NATO-exclusive endeavor. Twenty-two NATO members are also members of the EU, including Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Considering the economic impacts of Russian meddling in the Baltic states — also recent additions to the eurozone — it is in the interest of the EU to contribute to sustained stability in the region.

The Baltic states recently discussed the formation of a Baltic-based Russian-language news outlet to be broadcast throughout the region. The EU would benefit from supporting such an initiative. While financial backing would almost certainly be pounced upon by Russian media as indicative of Western propaganda, the establishment of Russian-language public service broadcasting (PSB), defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization as “broadcasting made, financed and controlled by the public, for the public,” would provide a reliable alternative information source. The Kremlin would likely attack any source that runs counter to its own narrative, Nadia Beard writes in the The Calvert Journal, but the fact that PSBs are “neither commercial nor state-owned” and are “free from political interference and pressure from commercial forces” would lend credence to their reports while serving to discredit claims that the network is simply a NATO or EU mouthpiece. EU support would be necessary in the application of available tax breaks and assistance in securing the network’s widest possible dissemination without interference or disruption by third parties. A transparent Russian-language news source widely available throughout the Baltic states would be critical to addressing the exclusivity of the Kremlin’s narrative.

Combating Russian propaganda cannot be limited to the establishment of one television station, however. The recently established Meduza, a Riga-based online news source, is one example of an independent Russian-language news outlet that can be a useful tool against Russian disinformation. However, these news organizations are fledgling and struggle to compete with Russia-based competitors. While Western institutions would be unwise to try to unduly influence these news outlets, providing independent Russian-language networks with unfettered access to NATO, the EU and their respective decision-makers will lend them greater credibility. Additionally, this will give NATO and the EU a platform from which to convey a message counter to the Russian narrative without forfeiting that which the Kremlin seeks to exploit: freedom of the press.

Additionally, the Baltic states, particularly Latvia and Estonia, should consider greater inclusion of their Russian-speaking minorities and wider acceptance of the Russian language. With laws in place that essentially force ethnic Russians to become more Latvian or more Estonian to fully participate in the political process, these states have put their Russian populace in the precarious position of having to choose between culture and citizenship. If they hope to compete against Russian influence, it may be time to accept the Russian minority as an integral part of their respective states. Ultimately, failure to accommodate the Russian minorities only pushes them closer to Putin and further under the sway of the Kremlin’s media machine.

In conclusion, in March 2014 Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Linas Linkevicius remarked, fittingly on Twitter: “Russia Today’s propaganda machine is no less destructive than military marching in Crimea.” Russia Today, one weapon in Vladimir Putin’s vast information arsenal, is indicative of the entire Russian media campaign — widely available and unencumbered by the burdens of journalistic integrity. The broad reach of the Kremlin’s information blitz and its use of harmful, divisive narratives could have a dramatic impact on the future of European security and economic stability.

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s

Comments are closed.