Is NATO Missing An Opportunity?

By Col. Giuseppe De Magistris, director, NATO Stability Policing Centre of Excellence, and Stefano Bergonzini, staff assistant, NATO Stability Policing Centre of Excellence

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is a political-military international organization that applies innovation and transformation to stay fit for purpose. This is a fundamental aspect of what is considered the most successful alliance in history. “The Alliance works,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said in 2019, “because through the decades, its members kept the commitment to protect and defend each other and adapted as the world around them changed.” Indeed, security challenges such as hybrid threats, the crime-war overlap as well as terrorism and insurgency, threats to human rights, human security and cultural property are significant and likely to become more relevant in the future. This can also be said for what the authors of the 2016 book, “Outplayed: Regaining Strategic Initiative in the Gray Zone,” called the “gray zone challenges, which are unique defense-relevant issues sharing three common characteristics — hybridity, menace to defense and military convention, and profound and paralyzing risk-confusion.” Intermediate force capabilities also are needed beyond presence but below the threshold of lethal force to deliver security without creating excessive collateral damage.

These challenges require innovative approaches and Stability Policing (SP) — police-related activities intended to reinforce or temporarily replace the indigenous police to contribute to the restoration and/or upholding of public order and security, rule of law, and the protection of human rights — represents one of NATO’s cutting-edge capabilities. It constitutes a flexible and adaptive tool, overcomes a rigid combat-only approach, and offers innovative and scalable responses by expanding the reach of the military instrument into the realm of policing and actively contributing to a comprehensive approach.

The ‘policing gap’ and the origins of SP

SP ante litteram was born with the deployment of the first Multinational Specialized Unit (MSU) to Bosnia in August 1998 as part of the NATO Stabilization Force (SFOR). At that time, the Alliance realized that neither its military might, nor the local police, nor the United Nations civilian police force were able to respond adequately to the security and policing-related needs of the local population. The MSU — envisioned, designed and led by the Italian Carabinieri with the support of Argentina, the Netherlands and the United States — represented the only policing tool within SFOR that was flexible and robust enough to fill the law enforcement vacuum in a hostile environment. That would include the capability void between the populace’s security needs and the inability or unwillingness of any indigenous police forces (IPF), other relevant actors (U.N., European Union, African Union, et similia) and NATO conventional, combat and warfighting means to properly address these challenges.

The authors of this article take pride in having served as NATO Military Police (MP) officers. It is an uncontroverted fact that military police existed previously within NATO and the U.N., but neither of those international organizations had pursued an increase, expansion or improvement of their MP capabilities to bridge the policing gap. In fact, they sought a more poignant, inclusive instrument, a tool inspired by a new vision, namely SP. Both SP and MP are united in a policing dimension that contributes to the improvement of the overall performance of NATO as a military instrument by adding a policing perspective that hitherto was often underestimated or neglected.

In 2016, NATO promulgated the Allied Joint Doctrine for Stability Policing (AJP-3.22). It states that SP can bridge the policing gap through one or a combination of its two missions. One of those missions, the reinforcement of the IPF, entails intervening to increase their capabilities and capacity and raise overall performance to acceptable levels, and encompasses monitoring, mentoring, advising, reforming, training and partnering. The other mission, temporary replacement of the IPF, may be required if the local force is missing or unwilling to carry out its duties. Normally a U.N. mandate initiates a North Atlantic Council decision to deploy personnel under an executive policing mandate. This might be necessary when other actors are not able, willing or ready to intervene. In fact, when a rapid policing intervention is required, especially in a nonpermissive environment, NATO SP could be the most suitable or actually the only viable solution until other actors from the international community can intervene, support and/or take over as a follow-on force, depending on a U.N. Security Council resolution or host-nation request.

SP can create new avenues to address traditional and emerging military problems with different policing means. Lethal/kinetic tools and procedures are supported, where appropriate, by policing, nonkinetic and less than lethal ones, significantly broadening flexibility in the use of force and applying intermediate force capabilities. These tools are aimed at war criminals, organized crime and transnational criminals, terrorists and insurgents, and violators of host-nation and international laws. This legal targeting affects adversaries by enforcing international and host-nation laws through investigation or arrest, limiting/restricting the mobility and liberty of offenders, seizing their assets and financial means, and dismantling their networks and structures. Dedicated SP lines of operation or SP elements within established lines of operation can deter, identify, locate, target and engage adversaries or spoilers, disrupt their networks and help attain objectives at tactical, operational and strategic levels in a military campaign.

An added benefit of this approach lies in further reducing the use of force and decreasing collateral damage while responding to the population’s security needs. Moreover, it epitomizes a constructive approach to security and contributes to improved acceptance and legitimacy, from the local level to the international level, while enhancing mission sustainability. SP further identifies, collects and analyzes law enforcement and crime information and disseminates intelligence, improving understanding of the operating environment. A number of factors can weaken the performance of the IPF in fragile states, including past, present and developing conflicts, and manmade or natural disasters. A weak or missing rule-of-law system in which individuals, public and private entities and the state are not accountable to the law, combined with a frail justice sector (police, judiciary and corrections) is likely to affect the efficacy of local police forces. Such a situation is likely to hamper governance and generate power and enforcement vacuums, which might be exploited by irregular actors, such as criminals, terrorists and insurgents, and produce considerable levels of insecurity and instability.

As a military capability that emphasizes a populace-oriented approach, SP operates within the area of stabilization and reconstruction and as a military capability for crisis management, striving for a comprehensive approach and human security. In fact, it fosters and seeks the best possible level of interaction with other international organizations, the host nation, and especially with the IPF, the populace and other actors, including nongovernmental organizations.

SP: When, where, how and who?

Does SP contribute to projecting stability? It has been argued that SP cannot contribute to the three NATO core tasks of collective defense, crisis management and cooperative security because it is framed solely within stability operations to bridge the policing gap. Yet, the evolving doctrinal framework contemplates that offensive, defensive and stability operations all encompass stability, enabling defensive and offensive activities that could be extended to SP, although limiting them to the policing realm.

Indeed, history shows that SP can and should be conducted throughout the full spectrum of conflicts and crises in all operational themes (from peacetime military engagement to warfighting), and before, during and after armed conflicts and manmade and natural disasters because the fragile host nation and its populace may require help to bridge policing gaps. By the same token, SP contributes to winning the war by affecting adversaries and enemies and by building peace, an aspect of fundamental importance in a connected, globalized world. Projecting stability is key to preventing and deterring crises, including armed conflict, and cannot be overlooked when addressing policing requirements. To this aim, SP is credible, instrumental and complementary to other actors’ efforts; this reasoning has often been demonstrated in NATO operations and missions.

Although “land heavy,” SP is not limited to a specific domain. To puruse criminals, terrorists and insurgents, it must be active on land, sea, in the air, in cyberspace and in the information environment. Urban and littoral settings are where most people live and where they will increasingly live. Since conflicts break out among people, and police are often the first responders to these crises, acquiring and using their experience and expertise is increasingly significant. This implies that urban challenges may progressively blur police and military functions as these areas of responsibility overlap. In turn, conducting military operations among dense civilian populations will require military personnel to have policing-like skills. In general, successful interaction between conventional military and policing components will require interoperability to ensure they can be ready, available and jointly deployable to permissive and nonpermissive environments.

An essential principle of SP states that “everyone can contribute to SP, but not everyone can do everything.” Policing is indeed very different from soldiering, especially in a fragile state. Basic SP activities and tasks — such as presence patrols, critical site security and election security — can be conducted by any trained, equipped and tasked unit. Higher level SP, such as investigating organized crime, disrupting international terrorist networks or mentoring host-nation senior leaders, requires a considerable level of expertise, experience and skill. A vast array of forces can and should contribute to SP, including gendarmerie-type forces — which are the first choice — MP and other military forces. Under a comprehensive approach, SP activities may include nonmilitary actors, such as police forces with civilian status, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations and contractors. This inclusiveness fosters interoperability, aims at enabling the Alliance to select the most suitable asset, and avoids missing opportunities.

The ‘missing’ capability: Why NATO needs an SP Concept

NATO lacks a capability that precisely defines the requirements for SP across the doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities and interoperability (DOTMLPFI) framework. During a force generation process, nations may provide the Alliance with SP contributions that lack police expertise since SP is not yet acknowledged as a capability within the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP). History shows that SP should be included in the planning process from the beginning and that a lack of expert and experienced policing personnel to reinforce or temporarily replace the IPF can have disastrous consequences. Considering a dedicated SP unit’s requirements during the next NDPP cycle and designating these requirements to specific NATO member states would ensure the capabilities will be available during any force-generation process. Within NATO, a concept is an instrument to coherently fill a capability gap. Unfortunately, a concept has yet to be adopted for SP.

There are inherent difficulties on the path toward an approved SP concept, including the differences between NATO nations’ police forces (military/civilian status, powers, jurisdictions, legal frameworks and national caveats). The guiding principle should always be that the Alliance’s strength lies in its cohesion and in the combined diversity of the contributions from all members, which is vastly greater than the sum of all the nations’ individual capabilities. It has been argued that the existence of AJP-3.22 suffices and a dedicated SP concept is not needed. But a doctrine is only one of the eight DOTMLPFI aspects needed to define a capability.

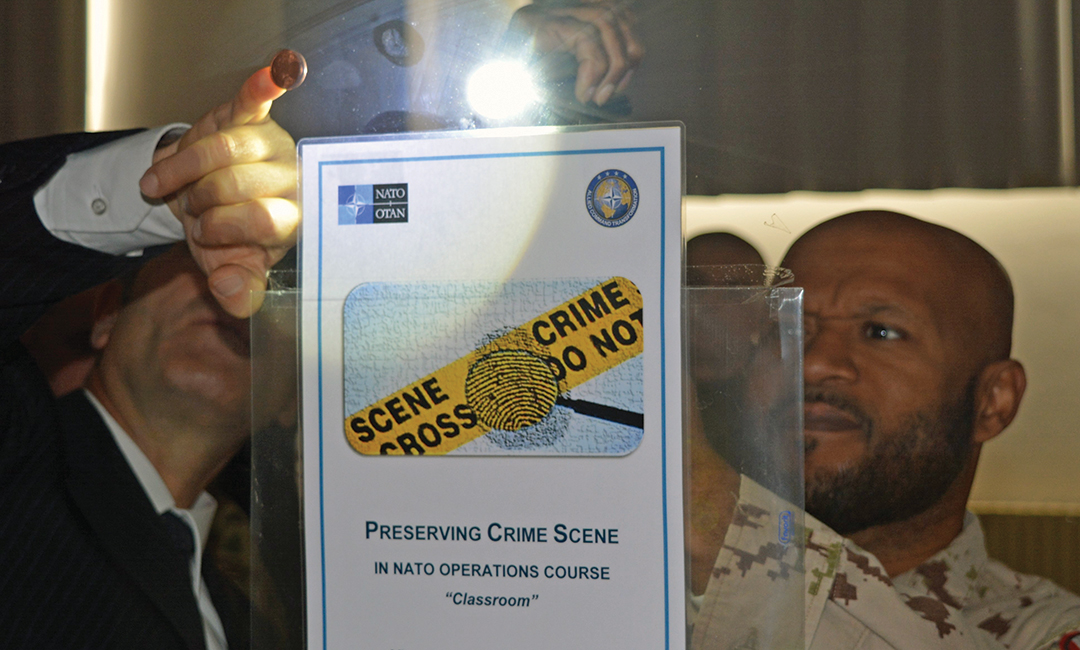

The NATO Stability Policing Centre of Excellence

The NATO Stability Policing Centre of Excellence (NSPCoE) is a think tank that encompasses a directorate and three pillars: the Doctrine and Standardization Branch, which develops concepts and contributes to improving the NATO doctrinal corpus with SP inputs and considerations, including developing the SP concept, reviewing AJP-3.22 and drafting ATP-103 (an allied, tactical-level publication); the Education, Training and Exercise Branch, which designs training curricula and hosts courses about SP and participates in exercises; and the Lessons Learned Branch, which gathers best practices and works the lessons-learned cycle to feed experiences garnered in operations and training into a database and ultimately into doctrine. The NSPCoE is the NATO hub of expertise for SP and strives to be the Alliance’s interface with international organizations and non-NATO institutions in the SP arena. The Czech Republic, France, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain and Turkey contribute to the NSPCoE.

What can SP do for NATO?

SP has existed under different names for more than two decades in NATO-led operations, often in hostile settings. Other international organizations, such as the U.N., the EU and the African Union, all possible partners for NATO SP, have performed and still perform SP operations, albeit under different names and perspectives. Despite this, SP is not yet sufficiently known, understood and adopted, even across NATO.

Policing local populations or re-/building IPFs have not been immediate concerns of NATO decision-makers. In some instances, they are considered the exclusive remit of other actors, including civilian organizations. That is an erroneous stance, especially considering that the latter cannot be deployed in nonpermissive environments, which could generate/deteriorate the policing gap. This attitude is gradually changing but too slowly. Lessons learned have shown that overlooking or delaying coordinated actions to address the policing gap inevitably affects the mission, delays or hinders the attainment of the desired NATO end state and may prevent NATO forces from disengaging. The police are the most visible manifestation of any government, being the institution that works for the population to provide security, to enforce the law and to respond to the public’s requests for assistance on a variety of issues. The lack of an effective, capable and trustworthy police force undermines the credibility of any government, with detrimental effects on its legitimacy and overall stability. Often, the burden for these shortcomings is carried mostly by a suffering civilian population. These situations are found especially in fragile states and in crisis or conflict areas, where the international community, including NATO, may be called to prevent crisis escalation and support peace restoration.

NATO military operations benefit from the inclusion of SP as a substantial contribution focusing on the IPF and the local populace. The aim of SP is to support the establishment or reestablishment of a safe and secure environment — restoring public order and security — and to contribute to creating the conditions for meeting longer-term needs with respect to governance and development (especially through security sector reform). In practice, SP supports nation building but also contributes to development of an IPF to answer the population’s security needs and increase cohesion and resilience. In the long term, the Alliance as a whole (its people as well as the structure, institution and processes) would profit from acquiring a more police-like mindset. The desired NATO end state might be better attained by not focusing solely on the conventional defeat of the adversary, but rather more on integrating noncombat approaches. This is particularly true in heavily populated environments such as in urban and littoral settings, where the attitude of the populace is to be taken into particular consideration and expertise in policing among civilians is clearly advantageous.

To protect civilians, as identified by the Policy on the Protection of Civilians (PoC), which includes an SP dimension, “all feasible measures must be taken to avoid, minimize and mitigate harm to civilians,” and SP can significantly contribute to this purpose in particular and to human security in general. Moreover, cultural property protection is one crosscutting topic within PoC, one in which a policing approach is critical to preventing and deterring relevant illicit activities. SP investigates related crimes, apprehends the perpetrators, and recovers the cultural property and the illicitly accrued wealth as restitution. Therefore, SP not only deprives the criminals of funding but also restores these funds to the host-nation economy, supporting its development overall and ultimately contributing to the battle of narratives. Among other significant niche areas in which SP can contribute to PoC are combating the trafficking of human beings, narcotics and weapons, enforcing antipollution and environmental protection laws, and countering labor exploitation.

In the book “Unrestricted Warfare,” by Col. Qiao Liang and Col. Wang Xiangsui of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, and in the so-called Gerasimov doctrine and countless papers on insurgency and modern warfare, terrorism and conflict, the commission of crimes is envisioned as a way to undermine the enemy. This is where SP embodies an innovation of paramount importance in tackling these crossbred perils. Current conflicts and crises present the traditional warfighter with complex challenges, including asymmetric warfare, hybrid threats, insurgency, lawfare, war-crime overlap, use of ambiguity, unconventional means, covert activities by state and nonstate actors, adversary communications (media, information operations, psychological operations, battles of narratives) and cyber threats, which cannot be addressed solely by combat and the use of lethal force.

In this vein, the Alliance is constantly assessing, evaluating and analyzing possible threats — particularly security-related ones — to devise appropriate responses. NATO’s Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area Concept focuses on pervasive instability, interoperability, a multidomain and 360-degree approach, and unconventional actors, while the NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept highlights the allies’ constant effort to innovate and adapt to remain fit for purpose. Moreover, the 2017 Strategic Foresight Analysis, looking at a time frame until 2035, includes insights and implications from probable interventions in heavily concentrated urban areas and the participation of a wide range of security actors. Likewise, the 2018 Framework for Future Alliance Operations looks at shorter-term challenges, particularly within warfighting and warfare development, to increasing the availability and number of SP personnel, to strengthening the capacity of existing MP capabilities and to generating policing-like skills to enable interaction with civilian populations as fundamental efforts. Finally, the NATO 2030: United for a New Era endeavor calls for periodic exercising of response options to hybrid threats and the closest possible cooperation within the enlarged DIMEFIL framework that, in addition to diplomatic, information, military and economic pillars, adds financial, intelligence and — most important for SP — law enforcement.

The overall evolution of the military problem needs tailored responses. One of them should be SP, an instrument endowed with an inherent flexibility within the force continuum. In fact, negotiation and mediation are envisaged together with a correct presence and posture to avoid the use of force, particularly lethal force, whenever practicable. This in turn implies that the Alliance embrace a transformation of its military instrument. Developing this capability and enhancing interoperability will require a concept to define

SP in all its aspects and enable its full integration.

An additional step sees SP enhancing the role of the Alliance by taking advantage of existing expertise, experience and networks in the field of policing and interfacing with relevant actors at different levels, especially the IPF and the local populace. SP is often misunderstood and sometimes downplayed if observed from a misinformed, outdated and exclusively combat-focused perspective. On the other hand, SP is an opportunity that the Alliance should not miss if it aims at moving forward in unison, remaining fit for purpose, and embracing innovation and transformation that possesses capabilities to carry out its tasks in a 360-degree approach.

Once approved, the SP concept will significantly enhance the outlook of the Alliance’s success, because the public security gap will be closed at the beginning of an operation, during the so-called critical golden hour. This is a crucial step that NATO must take to transition successfully to a follow-on mission, coupled with developing an assessment methodology to identify in advance the potential spoilers of the mission’s mandate. This is the very aim of the NSPCoE — to seize the moment for the benefit of the Alliance and the people we serve.

Editor’s note: This article was completed prior to the NATO summit in June 2022.

Comments are closed.