Uncertain Times Jeopardize Enlargement

By Pál Dunay

stablished 70 years ago with the signatures of 12 original members, NATO now has 29 members, meaning more than half are accession countries. Enlargement by accession occurred over seven separate occasions, and on one occasion the geographic area increased without increasing the number of member states when the German Democratic Republic (GDR) became part of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in October 1990.

The conditions surrounding the enlargements — the first in 1952 (Greece and Turkey) and the most recent in 2017 (Montenegro) — have varied significantly. The first three enlargements occurred during the Cold War and are regarded as strategic. They contributed to the consolidation of the post-World War II European order and helped determine its territorial boundaries. That first enlargement provided a NATO presence in the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region. It also culminated Greece’s somewhat hesitant integration with the West. Turkey was not a full-fledged democracy at the time, but strategic considerations prevailed.

The FRG’s accession 10 years after the end of World War II in Europe, in May 1955, had multiple consequences. It meant:

The FRG’s democratic record had been recognized.

The country could be integrated militarily, which signaled its subordination and a clear requirement not to act outside the Alliance.

The FRG’s membership in NATO created an incentive for the establishment of the Warsaw Pact, which followed West German membership by five days in 1955 and led to the integration of the GDR into the eastern bloc. This signaled the completion of the East-West division, at least as far as security was concerned.

The third enlargement — Spain in 1982 — meant membership for a country that had been integrated militarily, including the presence of U.S. bases on its territory, though the accession did not change much as far as the central theater of NATO’s operations in the Cold War was concerned. Although political considerations also contributed, strategic importance determined enlargements in the Cold War era.

The end of the Cold War and the unification of Europe entailed the long-awaited reunification of Germany. However, the conditions of German unity would have been better negotiated between the two German states than internationally in the so-called 2 + 4 Agreement. It was clear that the FRG’s international engagements would continue, including its memberships in NATO, the European Communities and other international institutions. However, it is not entirely clear whether a price has been paid for this negotiation considering Russia’s insistence that the West promised not to enlarge NATO to the east, or at least not to deploy NATO forces there. The West and Russia can be expected to continue an inconclusive debate over these terms with neither side providing any fully convincing evidence.

Strategic vs. Political

Whereas the Cold War enlargements have been characterized as strategic, the post-Cold War ones have been presented as political. However, their political nature does not mean they were entirely nonstrategic. The one factor common to the more recent enlargements is that every new NATO member since the late 1990s is a former socialist/communist country. Most had been members of the Warsaw Pact or territorially part of states that were among its members (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) or were republics of the only nonaligned socialist country, Yugoslavia (Croatia, Montenegro and Slovenia). It does not mean that the countries share the same history or political course. However, all of them had nondemocratic periods and all were unfamiliar with democratic control over the military. It is necessary to emphasize that political control of militaries was commonplace in those countries. But the supervision practiced by the communist parties represented a more direct involvement in military affairs. In most smaller socialist countries, unlike in the Soviet Union, the bargaining position of the armed forces was fairly weak and subordinate to the political leadership.

The post-Cold War enlargements were indeed political in some sense. Namely, the military capabilities of the candidate countries were of secondary importance. However, in 1999 when three former Warsaw Pact states (the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland) became NATO members, classic defense-related considerations were partially suppressed. NATO required only minimum interoperability. It could be said that the enlargement consisted of must-have countries. It was obvious that the Czech Republic and Poland — both having had a turbulent history with Germany, and Poland having had its tribulations with Russia and later the Soviet Union — could not be left out of the first eastern enlargement cycle. Concerning Hungary, the problem was somewhat different, though Germany must have thought some debt was owed because of Hungary’s actions in hastening the Iron Curtain’s fall in 1989. Hungary presented a special problem: It had no NATO neighbor and providing aid to its fellow members would be limited to what could be done with aircraft.

However, NATO was well aware of the interoperability limitations of eastern and central European countries. To address this shortfall, NATO — during its 50th anniversary summit in Washington a month after the first post-Cold War eastern enlargement — made several major decisions, including the adoption of the membership action plan (MAP). As will be demonstrated later, a full mythology has developed around this plan during the past two decades. It is important to emphasize that NATO wanted to lengthen the preparation time for membership. States aspiring to become NATO members enter the MAP and are helped in their preparation. Experts remain divided on whether the MAP actually facilitates membership.

The next eastern enlargement consisted of a more varied club, including states that missed the earlier round due to their own pace of development or for other reasons. The largest group that ever acceded to NATO consisted of seven members: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovenia. Although Vladimir Putin had replaced Boris Yeltsin as Russia’s head of state by then, opposition to NATO enlargement had not yet reached the level that has characterized the period since 2008. One of the main lessons of eastern enlargement is that it is a fair-weather process best carried out when there is no strong opposition.

The years that followed brought piecemeal advancement, with Albania and Croatia becoming members in 2013 and Montenegro in 2017. Those enlargements demonstrated the Alliance’s determination to keep the door open to states in the Western Balkans.

The Washington Treaty

It is important to contemplate certain legal and political issues when considering the three accessions since 2004. The foundation of NATO enlargement is Article 10 of the Washington Treaty. It states: “The Parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty. Any State so invited may become a Party to the Treaty by depositing its instrument of accession with the Government of the United States of America. The Government of the United States of America will inform each of the Parties of the deposit of each such instrument of accession.”

A closer look at the article’s meaning is essential. The conditions of accession are as follows:

Any state may seek membership. The conditions of statehood are defined under international law and are not very demanding. A state can be large or small and have a population in the thousands or more than a billion. Doubts have never been raised with respect to the statehood of countries with weak central authorities.

The state must be European, though what exactly constitutes a European state is a delicate question. What are Europe’s boundaries? Responses based on geography may not be identical to those based on politics. Geographically, one would conclude that states east of Turkey’s Asian territory are not in Europe. However, this matter has not been raised with respect to states in the South Caucasus. Hence, NATO’s current political geography would indicate that the border of Europe is on the western border of the Caspian Sea. These two conditions thus seem easy to meet.

Members of the Atlantic Alliance enjoy the full freedom to invite or not invite a state for accession. This is understandable because the treaty establishes a collective defense system. Of course, such an invitation must be preceded by mutual interest between the Alliance and a country wanting to join.

A state seeking to join must further the principles of the treaty. This may be perceived as ambiguous. However, the preamble and the first three articles of the Washington Treaty provide some context. There are references to democracy, the peaceful nature of the state and its readiness to maintain and develop a capacity to resist an armed attack. Has NATO been consistent as far as meeting its standards? This is subject to interpretation regarding the admitting of new members and when members backtrack on performance. While the Alliance has a mechanism for accession, it lacks one for expulsion. Unless a member wants to leave the Alliance, it will not be obliged to depart. Although this is an abstract possibility and has never been officially contemplated, being aware of it is important.

The last material condition may well be the most delicate. Namely, it requires that a state invited to join the Alliance be able to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area. This is certainly a perceptional requirement, and NATO members must be confident that the invited state meets it. Two concerns have emerged recently. First, what if a non-NATO member expresses the view that the Alliance’s acceptance of certain countries would threaten the security of the North Atlantic area? Legally, the situation is clear: A state that is not a NATO member has no say over enlargement decisions. However, the political reality may well be different. A large state that can influence European security may send signals that a potential NATO enlargement threatens regional security. Second, what if there are concerns that a country’s accession would not contribute to security because the state lacks adequate defense capabilities and could be perceived as a freeloader? There are two factors that may give such an impression: a low level of commitment by current members that haven’t delivered on promises made during their accession processes and the limited military capacity of some small countries. Taken together, these may cause some member-state politicians to hesitate before agreeing to underwrite the security of a state that may not be able or willing to contribute to collective defense.

The procedural conditions for membership are straightforward. Unanimous agreement among members is necessary to invite a state to negotiate its membership and then to become a member. The members and the accession state must ratify the accession protocol and the new member deposit its instrument of ratification with the U.S. government, the depository of the Washington Treaty. The process requires the consent of every NATO member on a number of occasions. If a member state thinks it might not support a country’s accession, it should immediately make that known and stop the advancement. This was the case in 2008 when some members opposed offering a MAP to more states that were once republics of the Soviet Union — in this case Georgia and Ukraine. In 1997, the opposite occurred, when the U.S. indicated early on at the Madrid summit of the 16 NATO members that it would support the three states up for accession, but no more.

Prospects

The concerns previously mentioned have some foundation. Russia has repeatedly expressed that it considers the advance of NATO infrastructure toward its borders to be a major security threat. Therefore, Russia has been strongly opposed to enlargement. It is every state’s right to agree or disagree with another state’s political orientation and aspiration to gain membership in an alliance. Every state is also entitled to express its views and rely on diplomatic and political means to influence partners. However, there are certain boundaries no state should transgress. The now 57 participating states of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe took the commitment in 1996 to “reaffirm the inherent right of each and every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve.”

This means that states have to respect each other’s choices. It goes without saying that disagreement on a country’s international aspirations should never reach the threat or use of force. This stems from basic principles of international law. Even if, as some assume, the hostilities on the night of August 7, 2008, between Georgia and Russia were started by Georgia, this would not have given grounds to de facto annex two parts of Georgian territory and unilaterally recognize them as “independent” states.

Three states of the former Soviet Union have joined NATO and two more have contemplated a future with the West, including NATO membership. Others have either become members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a collective defense alliance under Russian leadership, declared some kind of neutrality or demonstrated hesitation concerning their alignment.

Georgia

Georgia has committed to aligning its policy with the West, seeking NATO and European Union membership, since President Mikheil Saakashvili assumed power in 2004. The country has backed its words with action, including training its troops according to Western models and often in the West, participating in exercises with Western partners, purchasing Western equipment and contributing to Western efforts, such as the stabilization of Afghanistan and hosting former inmates from Guantanamo. It is clear that for 15 years, Georgia has been committed to becoming a member of the Alliance.

The greatest hurdle to Georgian NATO membership is Russia’s determined opposition. It has taken various forms over the years, including verbal warnings by Putin at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007 and at the Bucharest NATO summit in April 2008. Russia responds whenever Georgia’s membership moves high on NATO’s agenda. It aims to sow internal strife in NATO so that Tbilisi’s aspirations will not be supported by all 29 members. In strongly worded messages, Russia targets Georgians who want to avoid risks and prefer “stability.” Consider the words of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev on the 10th anniversary of his country’s war with Georgia, when he reacted to Georgia’s possible accession to NATO: “This could provoke a terrible conflict.” Russia is also making efforts to re-establish trade links severed during Saakashvili’s time in office.

More than 10 percent of Georgia’s external trade is now conducted with Russia, and that creates some dependence. Russia also addresses Georgia through propaganda, though Moscow’s ability to influence the population in the Russian language is declining, particularly among a younger generation that is less likely to speak Russian as a second language. Support for NATO in Georgia has declined somewhat from an extremely high level, but remains close to 70 percent. A major challenge for NATO is maintaining an interest in the Alliance among Georgians when it is clear that a membership invitation will not be extended in the foreseeable future. When the MAP was not extended to Georgia at the July 2018 NATO summit in Brussels, Tbilisi had to live with an upgrade to practical cooperation, or assistance with “countermobility, training and exercises and secure communication.”

Ukraine

Ukraine presents similarities and differences to Georgia. Unlike Georgia, Ukraine did not have a sustained commitment to NATO until 2014. After the Orange Revolution of 2005, Ukraine demonstrated a determination to get closer to NATO. However, by 2010, then-President Viktor Yanukovych informed NATO’s secretary-general that Ukraine’s membership should not be considered. But a little more than a year later, Ukraine returned to NATO seeking closer ties. However, the defense reforms begun after the Orange Revolution had largely remained on paper, and the resources allocated to the reforms disappeared. Moreover, Ukraine’s NATO aspiration was not always backed by popular support. Never before 2014 did a majority of Ukraine’s population favor joining NATO. But by 2017, NATO support had reached 54 percent in Ukraine, a country that neighbors four NATO members and three former Soviet republics. The 2014 Revolution of Dignity and the subsequent Russian annexation of Crimea — and Russian support provided to the separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions — fundamentally changed the dynamic.

Since 2014, a clear Western orientation has extended to every sphere in Ukraine, including trade, investment and defense. The high-intensity conflict in 2014 highlighted the shortcomings of Ukraine’s Armed Forces and contributed to a realization that modernization was needed. That has taken various forms, including Ukrainian training initiatives and Western contributions that involved the delivery of nonlethal equipment and, on a limited scale, defensive lethal weapons such as Javelin anti-tank missiles.

For various reasons, the alignment of Ukraine with NATO does not mean membership will occur in the foreseeable future. As President Barack Obama’s ambassador to NATO stated: “First and foremost … as it would be impossible to generate consensus in the Alliance to the invitation of a country [that] has a pending conflict with a mighty adversary and territory that has been occupied by it. It is open to question whether the internal dynamics of the conflict will result in a reassessment of Ukraine’s quest for NATO membership.” Russia has opposed NATO membership for former Soviet republics ever since the matter emerged early this century.

be whole, free and at peace. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Russia was not vocally opposed to the NATO accession of Balkan states, be it Bulgaria, Romania and Slovenia in 2004, or Albania and Croatia in 2009. However, lately Moscow is increasingly vocal in opposing continued NATO enlargement in the Western Balkans, and Western influence there more broadly. The reason for this new approach is open to speculation. But NATO enlargement in the region could not have been unexpected in Moscow, and that leads to one possible reason: Russia reassessed the strategic environment and concluded that NATO’s enlargement is to its disadvantage, irrespective of where it occurs. This means that according to Russia’s current evaluation, the geostrategic competition with the West extends to the whole of Europe.

In the 1990s, Russia was against NATO enlargement because it knew that in its weakened condition a change in the status quo would not be to its advantage. Today, Moscow is against enlargement because it wants to reverse history by changing the international order to its advantage. Because its international standing is so central to its domestic self-esteem, Russia can be expected to try to block enlargement for the forseeable future.

Montenegro

Montenegro, which joined NATO in 2017, simultaneously presented both dilemmas. Russia waged an unexpectedly strong campaign against its NATO accession, and doubts were voiced about Montenegro’s contribution to the collective defense capabilities of the Alliance. Russia thought it had a chance to influence divisions in Montenegro’s domestic politics. As a first step, the spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs criticized Montenegro for not holding a referendum on the matter. Indeed, Hungary and some other states held referendums on NATO accession and were fortunate that public support held firm. However, countries are under no obligation to ask the public to vote on accession; legislative approval suffices. The hostile Russian criticism should have served as a warning concerning Russia’s deep-seated dissatisfaction with the course of events. What followed was unprecedented. Russia engaged in a coup attempt to unseat the pro-NATO accession government and physically eliminate the longtime prime minister (now president). The deep and subversive interference in Montenegro’s affairs was organized from Serbia. When the failed coup attempt was revealed, Russian Security Council Secretary (and Putin confidant) Nikolay Patrushev urgently visited Belgrade, a sure sign of Russia’s illegal and camouflaged activity. Despite those efforts, Montenegro became the 29th member of the Alliance.

However, Russia’s objection was not the only hurdle to overcome. Questions were raised in the U.S. Senate about Montenegro’s military capabilities and its capacity to contribute to collective defense. This undoubtedly is a legitimate question that any Alliance member can raise because all members are expected to share in the risk of resisting external military challenges. The question demonstrated the changed atmosphere in NATO, where more than ever each contribution to the shared effort must be measurable. In spite of the concerns expressed by some senators, the Senate voted 97-2 to approve Montenegro’s NATO accession protocol in March 2017. Questions about contributing to NATO’s collective defense could be raised concerning every accession country, in particular the small ones with limited military capabilities. The issue re-emerged when U.S. President Donald Trump also questioned whether Montenegro could defend itself or contribute meaningfully to collective defense.

The less some new NATO members deliver on promises made in the accession process, the more difficult it may be to continue with enlargement. This presents a problem because it may be contradictory to the strategic necessity of enlargement. With NATO now consisting of 29 members, it is understandable that the number of European states still able to or interested in joining the Alliance is shrinking. Some — from Ireland to Switzerland and from Serbia to Azerbaijan — are not interested in NATO membership. Others face the obstacle of Russian opposition or are members of the CSTO. All of this raises questions about the future of enlargement.

North Macedonia

Macedonia looked like a credible candidate but had its prospective membership disrupted by a political dispute over its name. Greece objected to its name after Macedonia gained independence from the former Yugoslvia in 1991, so it entered the United Nations in 1993 under the provisional name, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, or FYROM. Five years later, Greece rejected Macedonia’s bid to join NATO and Macedonia protested to the United Nations’ International Court of Justice, which ruled in its favor in 2011. But it proved to be a pyrrhic victory. It did not bring about any change because no legal body can deprive Greece of its sovereign right to support or reject another state’s NATO membership. Macedonia’s political factions responded in 2018 by agreeing to the name North Macedonia as a compromise. This renewed negotiations for NATO membership, though Russia tried to block the process. However, the effort faltered when two Russian diplomats were accused of attempting to bribe Greek politicians to object to reconciliation with Macedonia. In turn, Greece decided to replace its ambassador in Moscow, resulting in a temporary chill in diplomatic relations.

Nationalist forces opposing the name change did their best to defeat the efforts even though it is in the country’s long-term interest to open the road to NATO (and later EU) accession. But in early 2019, Greece and Macedonia ratified an agreement to change the name to North Macedonia and put the country on a path to beginning two of the most important integration processes in Europe and the Euro-Atlantic area.

Finland, Sweden

There is a possibility that militarily nonaligned Finland and Sweden may also seek NATO membership. Russia attempted to deter the two states from moving in that direction while discouraging positive signals from NATO. Helsinki and Stockholm, aware of the controversy, continued to deepen their cooperation with the Alliance, but not wanting to risk regional stability, took no formal steps. However, the opening of the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in Helsinki — the first such center outside NATO territory, and thus a benefit to participating states as well as the EU and NATO — was a step that must not have been appreciated in Moscow.

Conclusion

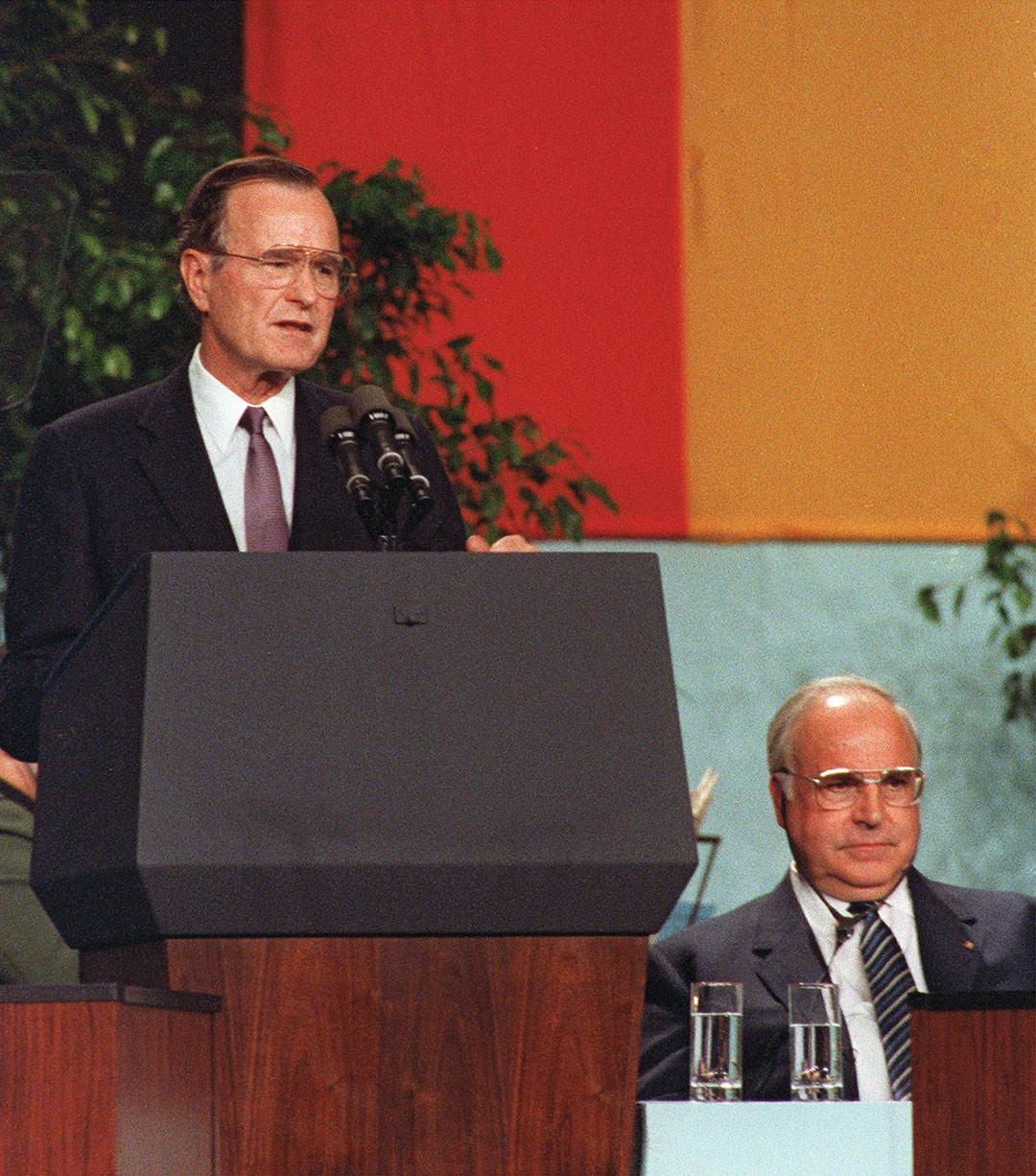

NATO enlargement — just as the enlargement of the EU — is not a l’art pour l’art process. It is about the development of states and the political model under which people are going to live. It is clear that the hope pursued since the so-called Mainz speech in 1989 by U.S. President George H.W. Bush about a Europe that is whole, free and at peace has not been achieved, and there is not much hope it will be attained anytime soon. There are different socio-political models that will have to coexist. A large part of Europe has made its choice. However, there is some unpredictability because some states that belong to core western institutions are not necessarily liberal democracies. There are some states and areas that are still in flux and the ongoing contest is to determine the political model they will follow as well as their international political alignment. There is no doubt in the West which model is preferable; however, this does not mean those forces will prevail without contestation.

The NATO enlargement process has been very successful overall, as it has helped many small- and medium-size states leave behind a gray zone that is occasionally referred to as “ferryboat country status.” Remaining in that zone — once called Zwischeneuropa (Europe in-between) by Czechoslavakian President Thomas Masaryk — in such ill-defined situations would have resulted in continuing rivalries for those countries, a grim prospect.

NATO enlargement in this sense is a process that has contributed to the strategic and political transformation and often the consolidation of the European continent. It also has contributed to the collective military power of the West. However, in that sense the jury may still be out as far as the contribution of smaller members to the Alliance’s net military capabilities. It is widely known that the small countries can contribute to the Alliance in specific, well-defined ways, but only scarcely to far-away, high-intenstiy conflicts. It is necessary to understand where the various members can make a difference and measure expectations against that understanding.

NATO’s doors will remain open, even if few states are expected to cross the threshold anytime soon. If European unification cannot succeed under the terms offered by the West, it is important to define the divisions and to guarantee that the divide causes the least pain to the European population.

Comments are closed.