Forecasting regional events in the near future

By Nataliia Haluhan

The Arctic ice cap has melted significantly over the past 50 years. Such climate change not only creates challenges and opportunities in terms of changing the region’s accessibility, it also shapes a new political context in the area. As a consequence, the security landscape is being rapidly modified, and that has implications in the new strategic documents of key regional and extraregional players.

The situation is becoming more uncertain in light of Russia’s Arctic Council chairmanship. Assessing the political aggressiveness levels of the main actors can provide foresight into possible scenarios during Russia’s chairmanship from 2021 to 2023. Determination of political aggressiveness is built on analysis of primary sources of Russian and U.S. law to track the evolution of the political narratives of key regional actors’ national strategies. In turn, the scenario analysis is built on the evaluation of relations within the great power triangle — Russia, the United States and China — in the context of a melting Arctic ice cap.

China will be the key player in influencing the region’s balance of power. Now that Russia is at the helm of the Arctic Council, the great powers may explore changes in political orientation.

Russian state strategy Arctic 2035

On March 5, 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin adopted the new Russian State Strategy on the Arctic. With Russia chairing the Arctic Council, it can be expected that Russia’s views on and aspirations in the Arctic will have greater influence during this period. To assess Russian political doctrine on the Arctic, discourse analyses and comparisons of the former and newly adopted strategies were conducted.

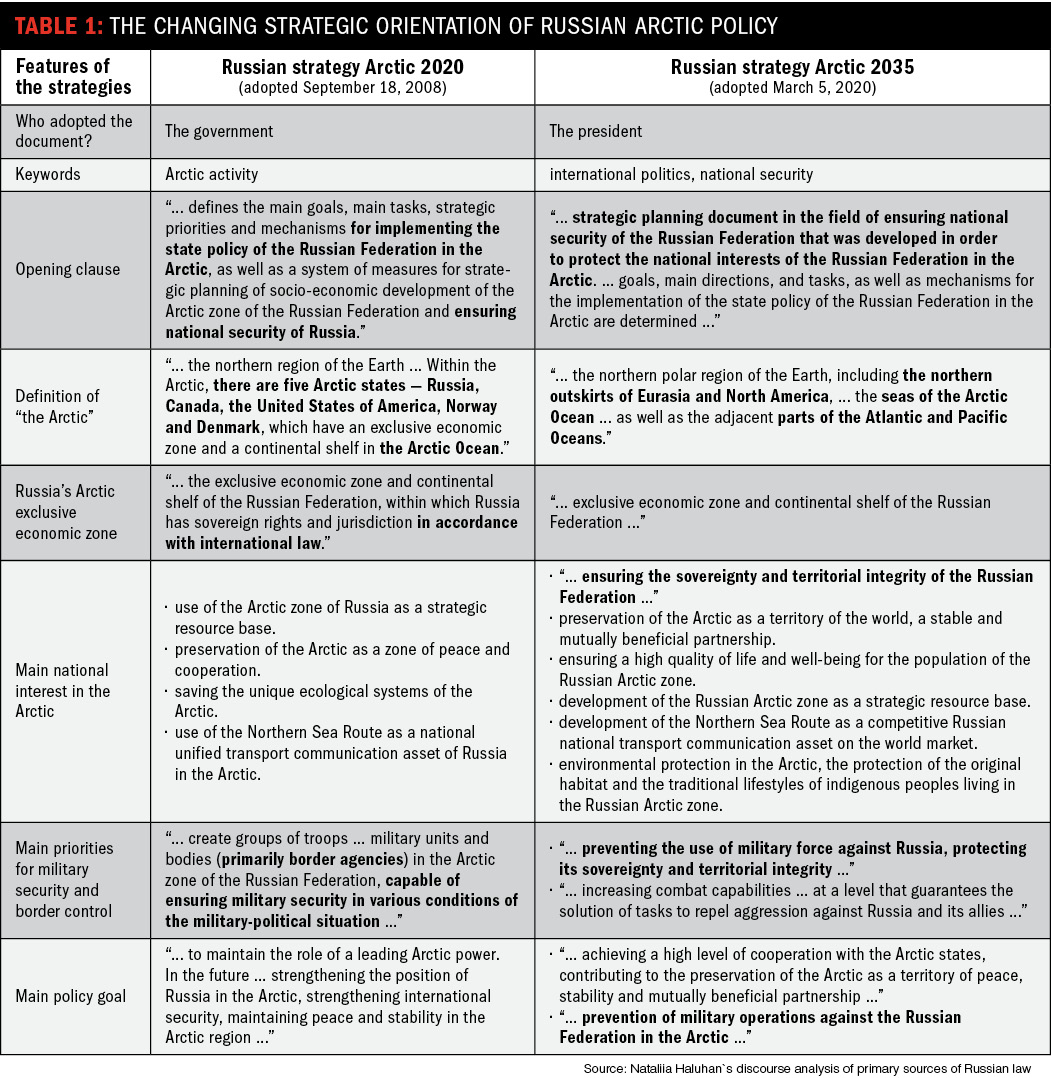

General trends regarding the changing strategic orientation of Russian Arctic policy (Table 1) include:

- The growing importance of the Arctic region within Russian foreign policy. It is an important signal that Putin has now taken the lead in implementing Russian policy in the Arctic, in contrast to the previous strategy, which did not specify the key actors.

- Sharpening political discourse on the Arctic region. This trend is apparent through the comparison of two opening clauses. Against the background of the more political character of the rhetoric in the 2008 strategy, the new document emphasizes the Arctic region as a matter of national security. The keywords used for online identification of the strategies additionally support this argument.

- Growing aspirations to change borders (claims made to the United Nations). The 2008 document’s definition of “Arctic” emphasized five Arctic states, considered only parts of the Arctic Ocean and, in principle, was mentioned only in the annex; the 2020 strategy includes a special clause with a definition that does not specify regional players and suggests a broader understanding of the region, including parts of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

- The shift toward securitization of the Arctic region. In the new strategy, Russia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity appear among its main national interests. Along with mentioning the preservation of national security at the beginning of the opening clause, this can be understood as a trend of growing interest in the Arctic in a security context.

- Militarization of the region by Russia. Military security is at the center of the new strategy. In contrast, the 2008 strategy reserved a lead role for border control issues. Furthermore, prevention of military aggression toward Russia in the region has newly emerged as an underlined task within the scope of the main end-goals of Russian Arctic policy.

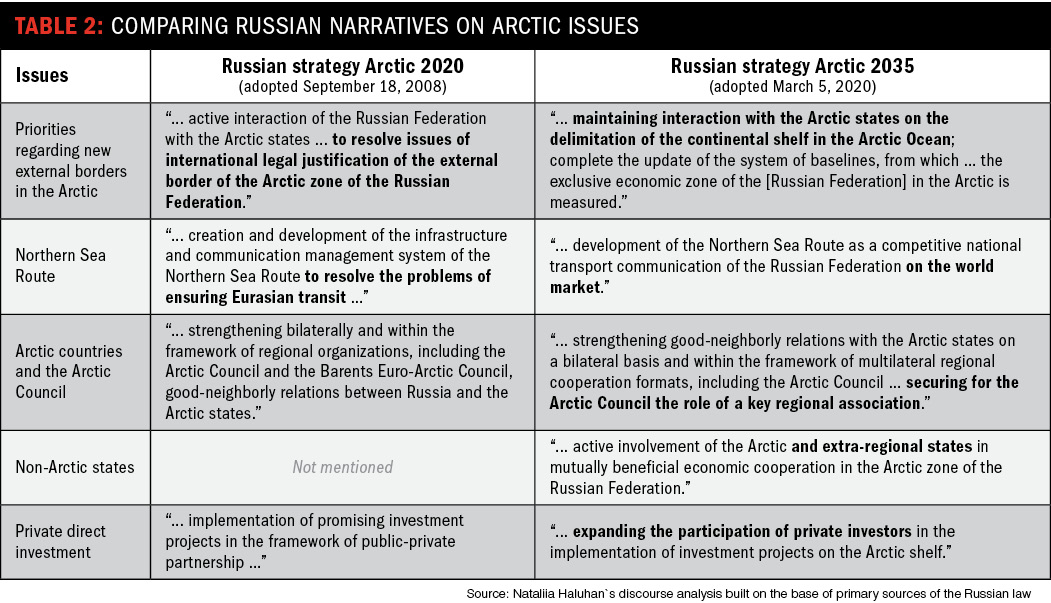

The evolution of Russian strategic narratives toward separate key issues in the Arctic region (Table 2) may be analyzed via the following tendencies:

- Fixation of new borders. While the 2008 strategy stated the intention to resolve the issue of external borders within the scope of international legal justification, the 2020 strategy stakes out a tougher position on the necessity of completing the final delimitation to the best interests of Russia.

- The Northern Sea Route as a tool to ensure global competitiveness. The old strategy defined the Northern Sea Route as a solution to trade cooperation between Europe and Asia. Due to its growing physical accessibility as Arctic sea ice melts and an ongoing regime of anti-Russia sanctions, the new strategy emphasizes a Russia-centric approach toward the development and usage of the Northern Sea Route.

- The growing importance of the Arctic Council to Russia. Though both the 2008 and 2020 strategies emphasize the need to develop cooperation within the region, the 2020 strategy additionally stresses interest in securing the Arctic Council as the key regional player. This may be seen as Russia’s attempt to gain extra benefits in light of its chairmanship.

- Russia is pursuing extraregional partnerships. The 2020 strategy particularly emphasizes the opportunities for involvement of other countries in the region and, specifically, the presence of private investors. Given Russian-Chinese negotiations on cooperation in the Arctic, that can be viewed as a de facto acceptance of Chinese claims on rights as a “near-Arctic state,” introduced by the Chinese white paper on Arctic policy in 2018.

In general, the growing importance of the Arctic to Russia may be seen through the lens of the unique opportunity it provides for Russia to become, for once, a real maritime superpower. The importance of this is pointed out by the Russian Maritime Doctrine, adopted in 2015, which voices the strategic goal to preserve and protect “the status of a major maritime state.”

Evolution of U.S. national strategies on the Arctic region

Though Russia’s new Arctic strategy shows the growing trend toward the securitization of the region, Russia is not the only regional superpower with developing ambitions. In general, the leading narratives of U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) strategies toward the warming Arctic region mirror Russia’s focus on the tightening geopolitical competition (Table 3).

Discourse analysis of the leading narratives of the three U.S. strategies on the Arctic, introduced in 2013, 2016 and 2019, respectively, shows the intention to increase the militarization and securitization of U.S. Arctic policy. This argument is supported by the changes in DOD objectives. Thus, maintaining a favorable balance of power and the ability to compete for that are incorporated in a 2019 strategy that preserves a peaceful, stable and secure Arctic region. Against this background, the new concept of ways and means introduced by the DOD, and especially “the will to strengthen the rules-based order in the region,” may be viewed as a challenge and a readiness to engage in great power competition in the region.

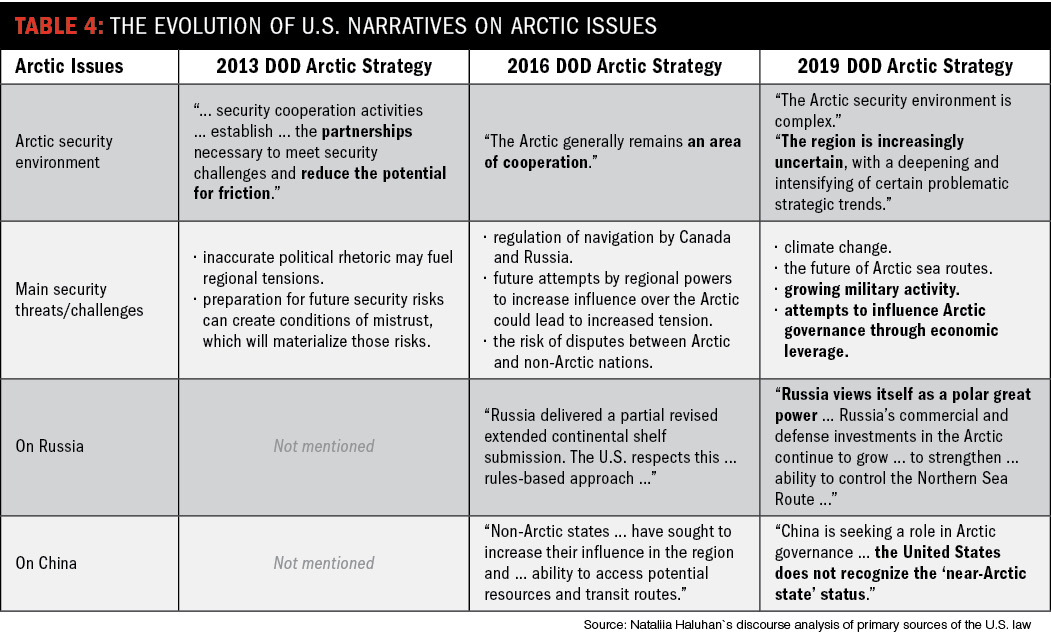

The comparison of more specific issues (Table 4) provides the opportunity to analyze the challenge in detail. The evolution of U.S. national strategies on the Arctic is built on the following main trends:

- The Arctic region is about to become a new stage for the global security dilemma. Against the background of a rather peaceful assessment of the Arctic security situation by the DOD’s strategies of 2013 and 2016, the most-recent 2019 strategy cardinally changes those views. Though the 2019 strategy emphasizes the low probability of conflict in the near future, it simultaneously states the necessity for the U.S. to ensure flexibility for global power projection to limit Chinese-Russian opportunities for leveraging the region. That approach can fuel tougher competition over access to Arctic shipping routes and natural resources, as well as create new friction points within a broader global security context.

- The U.S. does not recognize any claims to the Arctic by extraregional actors. The 2019 strategy clearly voices the U.S. position toward Chinese attempts to claim a “near-Arctic state” status. The U.S. stance clashes with the Russian position on de facto recognition of the introduced rights of the extraregional states. Furthermore, in line with the 2017 U.S. Security Strategy, the 2019 U.S. Strategy on the Arctic underlines a Russian and Chinese active presence in the Arctic region as a security threat.

The growing securitization of the Arctic region in U.S. policy may be additionally demonstrated by comparing the repetition frequency of existing geostrategic competitors — China and Russia — in the U.S. national strategies of different years. In 2013, the DOD Arctic Strategy mentioned Russia only once, but in 2016 and 2019 it was mentioned 25 and 26 times, respectively. That can be explained by worsened U.S.-Russian relations after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014. In parallel, China was not mentioned in 2013 and only once in 2016. However, in 2019 the word “China” was used 20 times. Given that China issued the white paper on the Arctic in 2018, such growing attention from the U.S. mirrors its disagreement with the Chinese self-proclamation of special “near-Arctic state” status.

Strategic foresight for 2021-2023

Analysis of the recent development of Russian and U.S. policies toward the Arctic shows growing securitization of the region from both sides. Given existing regional political dynamics, China’s leveraging role should be additionally emphasized. One recent example of such leveraging is that on April 24, 2020, the U.S. decided to extend economic aid to Greenland and set up a consulate in the Danish territory to counter the growing presence of China and Russia in the Arctic. It was done, first of all, as an answer to increasing Chinese investment in the economies of the smaller Arctic states.

In general, strategic forecasting of potential regional events is a complex problem. Russia, which controls the Northern Sea Route, is one of the key players in the Arctic. As chair of the Arctic Council, Russia can increase its political influence in the region. Simultaneously, the new Russian strategy regarding the Arctic accepts the involvement of extraregional countries and defines the need to attract financing from private investors. That may be seen as a consequence of the Russian-Chinese agreements on cooperation because Russia needs Chinese money to pursue its agenda in the Arctic. At the same time, the COVID-19 crisis may significantly affect preexisting plans. In contrast, the U.S. is one of the most powerful actors in the Arctic region, and it does not accept the “near-Arctic state” concept. In general, U.S.-Chinese relations should be seen through the lens of simultaneously high levels of competition and interdependence. However, tensions may change significantly after the COVID-19 crisis due to economic reasons.

Given these arguments, at the strategic level the balance of power — and as a consequence, the degree of stability — in the Arctic region post-COVID-19 and during the Russian chairmanship of the Arctic Council may be addressed through two determining factors: the level of cooperation between Russia and China, and the state of China-U.S. relations.

Given these factors, the following three main scenarios are plausible in 2021-2023:

- China pleases the U.S. — Preferable scenario

Description: After the COVID-19 crisis, China decides to seek a new level of cooperation with the U.S. to keep American enterprises and maintain the level of globalization. Simultaneously, China stops actively contributing to the Russian agenda in the Arctic both politically and economically.

Results: The balance of power in the Arctic remains stable. The U.S., as the most powerful player in the region, preserves the existing tendency toward U.S. primacy. Non-Arctic states limit their activity in the region. Russia cannot get enough external support to pursue its Arctic policies.

Stability of the system: Hegemonic theories of international relations suggest that unipolar stability will be built on “the leading state’s management of the system within a hierarchical order” until the challenger is not powerful enough to overcome the hegemon. - China goes on its own — Probable scenario

Description: After the COVID-19 crisis, Russia succeeds in resetting dialogue with the European Union and gains European foreign direct investment to its projects in the Arctic, strengthening Russian-European ties. Anti-globalization narratives are articulated in response to COVID-19. China becomes an independent great power and turns to regional players and other non-Arctic states with Arctic aspirations. The U.S. continues to counter China’s “near-Arctic state” policy.

Results: More active actors appear on the Arctic stage. A multipolar system in the region is shaped. Thanks to the melting Arctic and the “near-Arctic state” concept, even traditionally landlocked countries (for instance, Kazakhstan) articulate their maritime aspirations.

Stability of the system: Classical realists believe that the multipolar system is the most stable because “multipolarity creates a larger number of possible coalitions that might be formed against any appearing aggressor.” The theory suggests that such a system will help create deterrence against possible aggression. Thus, multipolarity may be seen as a diversification — a kind of political insurance — that helps to mitigate the risks of global power competition. - Chinese-Russian cooperation in the Arctic

flourishes — Worst-case scenario

Description: China pursues cooperation with Russia, and relations with the U.S. remain tense. Russia, with the economic support of Chinese investment, pursues its aggressive Arctic policy. The U.S. confronts a growing Chinese-Russian presence in the region.

Results: The bipolar system is being shaped. Militarization and securitization of the region are growing.

Stability of the system: Classical realists argue that “polarization of the alliance system around the two leading powers increases the risks of escalation.” One may consider this situation the most unstable.

To ensure the more stable and preferable scenario, the close and growing Russian-Chinese cooperation in the Arctic should be counterbalanced. To achieve that, consider the following recommendations for the democratic Arctic coalition:

- Engage with other players: In particular, that means the use of the foreign aid, foreign direct investment and diplomatic efforts by the U.S. to counterbalance major Chinese investments in Denmark and other smaller Arctic states, such as Iceland;

- Rebuild economic relations with China: To limit the Chinese presence in the Arctic and ensure a post-COVID-19 global economic revival, it can be beneficial to reset U.S.-Chinese economic relations in more traditional domains, exchanging limitations to China’s Arctic presence for other economic benefits;

- Reform the World Trade Organization (WTO): Absent definitions for “market” and “developing” economies, as well as rules for “graduation,” a new category should be established to stop giving opportunities to actors, in particular China, to manipulate existing developing-country trade preferences. Political will and international consensus are crucial to clearly define WTO categories and prevent China from receiving these preferences.

That may to some extent help resolve the existing U.S.-Chinese trade conflict and reboot mutually beneficial cooperation. As a consequence, China may agree to limit its presence in the Arctic region to avoid spoiling the normalization of U.S.-Chinese economic relations.

Conclusion

The Arctic region is characterized by the presence of two strategic rivals: the U.S. and Russia. Both are Arctic countries. Until very recently, their neighborly relations in the Arctic could have been described as a “silent confrontation.” However, due to climate change and melting sea ice, the region is receiving much more strategic attention.

In 2018, China issued its white paper on the Arctic and became the first non-Arctic state to proclaim itself a “near-Arctic state.” The U.S. has strongly opposed that concept, while Russia articulated limited support. Thus, that white paper not only gave birth to new political aspirations and a new definition but also incorporated a third great power into the regional equation. Even more important is that the Chinese political agenda sharpened the regional Russia-U.S. confrontation. These trends may be traced through the evolution of U.S. and Russian national strategies for the Arctic in general and toward the securitization of the region in particular.

As a consequence, in this analysis, China has balancing leverage, and its political aspirations are able to change the security landscape of the Arctic region in the near future.

Comments are closed.