The China-Russia Relationship is More Partnership of Convenience than Alliance

By Falk Tettweiler, Marshall Center researcher and analyst

The February 4, 2022, joint statement from China and Russia has widely been interpreted as a signal of deeper cooperation between the two major challengers to the liberal world order. Some have gone so far as to assess it as a sign of an institutional axis, or even an alliance. However, the lack of official Chinese support for Russia’s illegal attack on Ukraine is sowing some doubts regarding this argument. Deeper scrutiny of existing cooperation between Russia and China, and the declarations in the joint statement, show that there are common interests and the perception of a common opponent — the “liberal West” — but the uninspiring joint statement also reveals that they do not share a common vision of the future. The two countries might, in fact, be less aligned than it appears at first glance.

Challenging the liberal West and the existing world order requires a safe and secure home base for both China and Russia. Consequently, the common security interests of both countries, presented in the joint statement, lie mainly in ensuring their visions of security and stability in their common adjacent regions, countering interference by outside (Western) forces in what they consider internal affairs, and opposing attempts by their citizens to gain more freedom, which are often referred to as “color revolutions.” However, besides these common interests, there are huge differences in their respective visions of a new world order. In comparison to Russia’s negative vision, conceptualizing itself as a victim of the West, the Chinese vision might be seen as a real alternative by some countries. Additionally, the relationship between Russia and China has been marked by decades of deep mistrust. It can be predicted that these differences will prevail in their future relationship, despite increased cooperation in some fields.

China-Russia military cooperation has a decadeslong history of remarkable ups and downs. It has never been animus, but always distrustful. Although the relationship has been asymmetric until relatively recently, with the Soviet Union/Russia as the provider of both technology and know-how, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) never accepted their more powerful partner as a leader or dominator. Instead, the CCP used the Russians as a means to an end. The Soviet Union began supporting the newly formed communist movement in China in the 1920s and played an essential role in building the Red Army during the Chinese civil war. Thus, it helped Mao Zedong, who famously said that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” to defend his power position against rivals inside the CCP and against external enemies, such as local war lords, the Kuomintang and the Japanese Army. The Soviets continued to support the armament of CCP forces — renamed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) — after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. This helped cement Mao’s rule over the CCP and the PRC.

With Soviet support, the CCP quickly built a credible communist force in the region and a sustainable armaments industry. For example, applying Soviet know-how, the Chinese armaments industry engineered its first indigenous fighter aircraft (Dongfeng-101, later renamed Shenyang J-5) in 1956 and its first nuclear bomb in 1964. But the validity of another famous Mao quote, that “whoever wants to seize and retain state power must have a strong army,” also proved to be true in the Soviet-Sino relationship a few years later. As the CCP grew in confidence, ideological differences became more obvious. Border disputes between China and Russia became hot in the 1960s and led to an open border conflict in 1969. In 1971, the Soviet-Sino split was complete as the two countries supported opposing sides during the war between India and Pakistan. Despite both being communist regimes, China and the Soviet Union were more opponents than partners in the following almost two decades. During this period, military cooperation came to a halt. It was not until after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, with the CCP’s resulting political isolation and the rapid decline of Soviet economic power, that the two countries restarted military cooperation.

After revitalizing its relationship with Russia in the 1990s, the CCP relied on Russian foreign military sales to modernize the PLA’s outdated military equipment. The United States’ successful military campaign during the 1991 Gulf War was an eye-opener for PLA strategists and led to major military reforms, and also made Russian equipment and know-how more than welcome. Additionally, the PLA started participating in multilateral military exercises within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2003, and in bilateral exercises with the Russian armed forces in 2005.

During the following years, the PLA remained an important power instrument for the CCP, but the country’s fast economic growth was the paramount objective and the political leadership’s main focus. “Getting rich” was the slogan during this period, which ended with the election of Xi Jinping as general secretary of the CCP in 2012. The new slogan of the Xi era is “getting strong” and the PLA has a vital role in the CCP’s plans for China’s future. The Mao dictum that “whoever has an army has power” has regained its relevance for realizing the “China Dream” and the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” — two central concepts of Xi’s agenda.

The importance of the PLA to Xi’s plans is reflected in the very ambitious timeline for its reform. The PLA wants to become a world-class force that is a peer to the U.S. military by the middle of the 21st century. The PLA is training and equipping for a new kind of warfare of integrated joint operations in all domains. This refers to the domains of land, sea, air, cyber and space, as well as strongly focusing on the cognitive domain. Some milestones to achieving that goal are mechanization by 2020, which was slightly delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and complete modernization by 2027. The latter includes the first as well as “informatization” and the PLA’s ability to conduct “intelligentized” warfare. “Informatization” means that the PLA must be equipped to conduct integrated joint operations in all the above-mentioned domains, first on a local level and later on a global level. Additionally, the aim of “intelligentization” requires the consequent use of science and technology for artificial intelligence, which has been used to monitor Chinese society. CCP leadership has made it clear that the informatization and intelligentization are far more important than full mechanization because the PLA recognizes that the days of solely mechanized warfare are over. Therefore, the science and technology sectors play an invaluable role in the successful implementation of PLA reforms. Thus, they cannot be seen as separate from the military, as in some Western countries.

Following the intelligent integration and integrated joint operations approach could lead to a real revolution in military affairs. It means that the PLA could abandon Western concepts of warfare and lean more toward a traditional Chinese approach to strategy. The PLA’s aim would no longer be to simply accelerate its own observe-orientate-decide-act (OODA) loop and beat the opponent on the battlefield, as in typical Western concepts. The objective would be to manipulate the entire OODA loop of the opponent to “win the war” before a potential violent confrontation. If the PLA shapes the perception and orientation of the opponent, their decisions, actions and the feedback loops can be influenced in a way favorable to the PLA. Implementing this idea — understanding armies as systems and conceptualizing war as a confrontation of these systems — means that a war could be won without fighting or before the fighting starts. This revolutionary change in concepts would mean a return to Sun Tzu’s approach to strategy and turning away from the common interpretation of military theorist Carl von Clausewitz regarding the value of decisive battles.

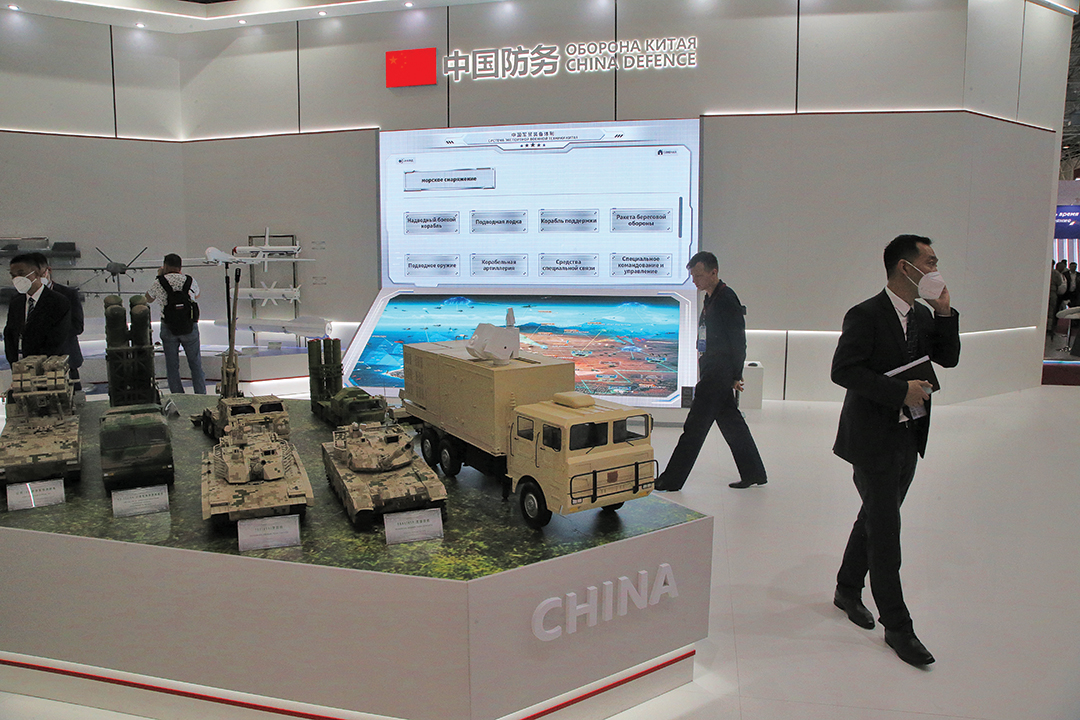

These conceptual deliberations also have implications for the future development of China-Russia military cooperation. The significance of a strong science and technology sector in the PRC was already articulated in 2015 in the “Made in China 2025” initiative and in 2020 with the “dual circulation” idea. China’s ambition to become the leader in certain technology domains is reflected in its armaments industry, which is closely linked to its technology industry. The aim to domestically produce high-tech products is also applicable to the Chinese armaments industry, which is experiencing rapid modernization and greater self-reliance and autonomy. Consequently, China has become less dependent on Russian foreign military sales. Currently, China mainly imports Russian-built aircraft engines, although China’s aeronautics industry is catching up. Additionally, the existing China-Russia relationship and military cooperation is strained by China’s practice of copying and reverse-engineering technology and equipment, and by its theft of intellectual property and its industrial espionage; for example, Chinese cyberattacks on Russian arms-producing companies.

As mentioned, since 2003 the second pillar of China-Russia military cooperation has been military exercises. With the latest iteration of the multilateral Vostok exercise in early September 2022, there have been at least 79 bilateral and multilateral training events since this cooperation began. Joint exercises benefit both sides. While Russia alleviates its political isolation and gains the opportunity to advertise its military equipment, the PLA gains operational experience in a variety of geographies and climates, and learns tactics and procedures from the more experienced Russian armed forces. With the shrinking Russian technological lead and the obvious underperformance of Russia’s armed forces in its war on Ukraine, the tangible benefits for the Chinese side will decrease in the foreseeable future. During Vostok-2022, the PLA for the first time trained with Chinese-manufactured equipment only. As soon as Chinese-produced military equipment becomes equal or superior to Russia’s, China could use multilateral exercises to promote its own equipment and thereby compete with Russia. This would again have a negative influence on the bilateral relationship because foreign military sales are, next to natural resources, an important source of income for the Russian state. Therefore, it is very likely that the mutual benefits of future bilateral and multilateral exercises will be limited to sending political and strategic signals toward the U.S. and its allies in the region, and to furthering transparency between increasingly competing China and Russia. The latter could reduce tensions in the relationship between the two countries.

All in all, China-Russia military cooperation seems to be at a tipping point and leaning toward decline. The ongoing war in Ukraine proves that Russia is still very much stuck in a more traditional concept of warfare. Although Russia’s deception operation prior to the actual invasion matched the direction of Chinese thinking on the future of warfare, Moscow’s poor assessment of the real situation on the ground in Ukraine and its lack of preparation of the cognitive battlefield demonstrate that Russia is not yet there. As Russia’s armed forces were unable to meet expectations as a role model for future competition with the U.S., and the technological lead of the Russian armament industry is shrinking, the CCP will not invest much in stronger cooperation in these fields. However, this will not lead to an end of military cooperation between Russia and China unless Russia crosses Chinese red lines, such as using nuclear weapons against Ukraine. But the cooperation will merely be symbolic and on a political level to challenge the U.S.-led liberal West — with Russia likely the junior partner in the future relationship.

Comments are closed.