Terrorist attacks in Europe highlight the need to monitor European extremists fighting abroad

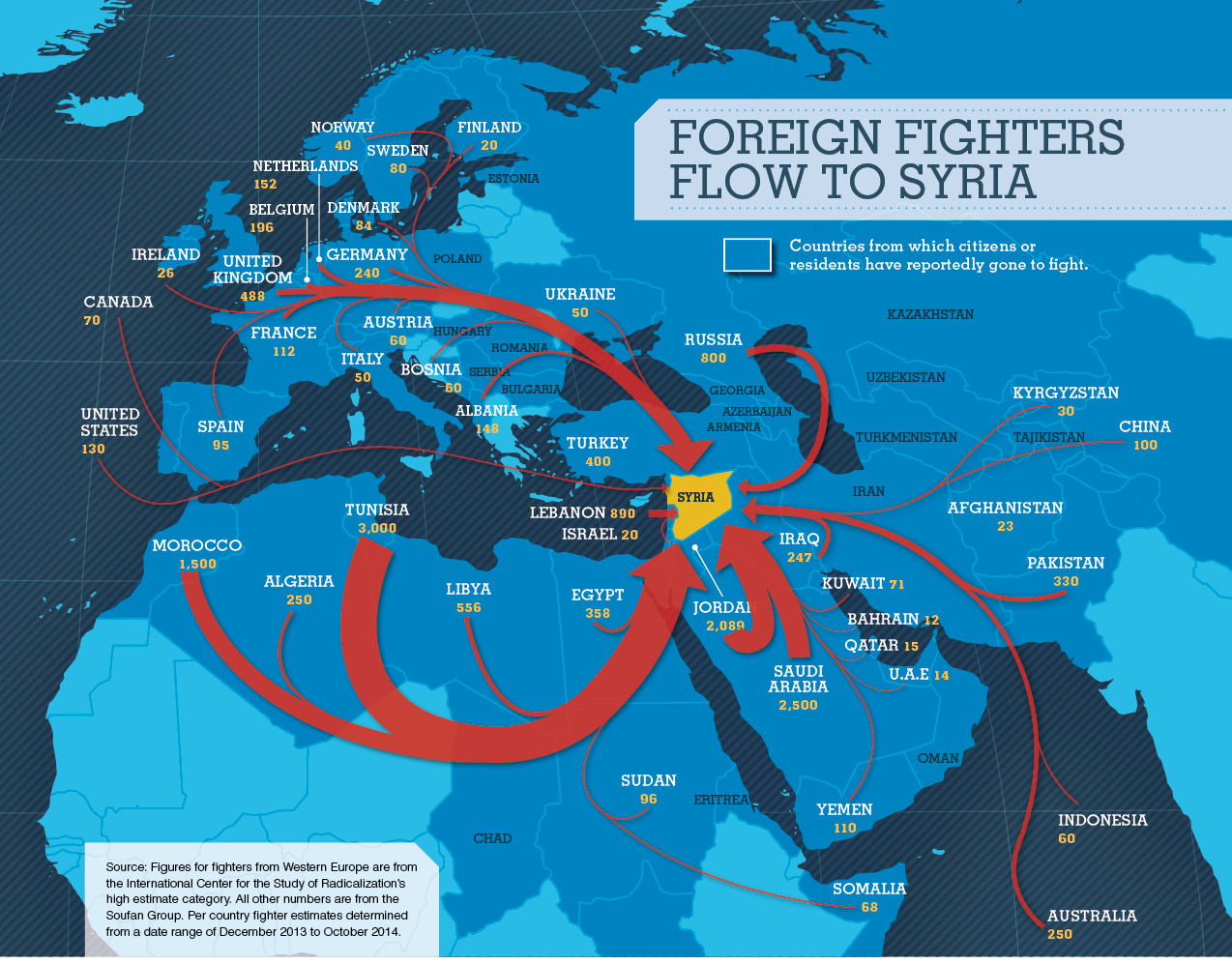

Faced with the prospect of 3,000 of its citizens fighting in Syria and Iraq, European governments are experimenting with different techniques to prevent returning fighters from waging war back home. These policies range from the severe — arrest, detention and loss of citizenship for returnees who had fought in the Middle East — to the softly sociological — counseling, rehabilitation and job placement for former jihadist recruits.

What the governments all have in common is a determination to confront the terrorist threat from radicalized fighters professing a violent strain of Islam. That threat was illustrated by the January 2015 murders at a magazine office in Paris committed by Islamic radicals who had been recruiting fellow extremists to fight in the Middle East. Europeans have most often joined the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and al-Qaida.

“The problem with Syria is the scale, the number of people going,” Thomas Hegghammer, director of terrorism research at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment in Oslo, told Bloomberg Businessweek in December 2014. “Even if the blowback ratio is low from Syria, the absolute numbers are going to be relatively high. … We are going to have radical Islamic communities in Europe for another generation — substantial ones.”

Preparing for the worst

The Syrian civil war has drawn larger numbers of radicalized European Muslims than earlier conflicts such as those in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Europol Director Rob Wainwright dubbed the ISIS returnees, who could eventually number as many as 5,000, Europe’s greatest security threat in more than a decade. The prospect that many of these battle-hardened extremists will return to Europe with a taste for inflicting violence has inspired governments to act.

Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom have been conspicuous in their expanded use of surveillance, arrest and detention for returning ISIS fighters, especially those who have expressed hostility toward their home countries. Pinpointing exact numbers is difficult, but officials suspect more than 1,000 Austrian, Belgian, British, Dutch, French, German and Norwegian citizens have gone to Syria.

Germany has attempted to seize the passports of would-be jihadists to prevent them from traveling overseas, and Austria has debated stripping citizenship from the dozens of extremists returning home from Syria. Nationwide bans on ISIS’ black flag have become increasingly common. British Prime Minister David Cameron warned that anyone found with such paraphernalia could be arrested. “Working with our partners, we have stopped three UK terrorist plots in recent months alone,” Andrew Parker, chief of MI5, Britain’s domestic intelligence service, announced in January 2015.

Muslim communities in the Balkans also have supplied recruits for the Syrian civil war, forcing countries such as Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia and Serbia to update counterterrorism laws. Some of these Southeast European recruits have been lured to the Middle East less by ideology and more by cash bonuses offered by jihadist groups, news reports said.

Driving many of the legal changes are conspicuous terror attacks committed by Europeans regarded as ISIS and al-Qaida accomplices and sympathizers. The first known attack by a Syrian returnee occurred in May 2014, when a French-Algerian named Mehdi Nemmouche shot and killed four visitors to the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels. Nemmouche had fought on the side of Islamic extremists in Syria and pledged to take the fight to Europe.

In early January 2015, two gunmen executed 12 people at the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo, a humor magazine known for satirizing religion, including Islam. Those murders, as well as four related killings at a kosher supermarket, represented the worst single terrorist event in France in a generation. Within a week, al-Qaida had claimed credit for the atrocity.

A softer approach

Denmark can serve as a laboratory for an alternative approach that treats returning ISIS fighters more as wayward youth than potential terrorists. An experimental program in Aarhus, the country’s second-largest city, provides counseling, job placement and free schooling for returning fighters professing views abhorrent to most Danes.

The Danish program started as a rehabilitation technique for neo-Nazis, but it was expanded to include Islamic extremists living in Aarhus’ large Muslim community. As of early 2015, none of the returning fighters engaged in the program have been caught committing violence at home, but few seem repentant. Danish officials admit that most of the enrollees refuse counseling meant to steer them toward a less militant version of Islam.

“These are young people who have turned to religion at a very difficult time in their lives, and they are dealing with existential questions about going to fight for what they believe in,” Aarhus Mayor Jacob Bundsgaard told The Washington Post. “We cannot pass legislation that changes the way they think and feel. What we can do is show them we are sincere about integration, about dialogue.”

One such fighter featured in several articles was described as strutting down the streets of Aarhus — more hero than outcast — wearing military camouflage from his time in Syria. The 21-year-old son of Turkish immigrants admitted he longed for an Islamic caliphate and approved of executing captured Syrian and Iraqi soldiers. “I know how some people think. They are afraid of us, the ones coming back,” the former fighter told The Post in late 2014. “Look, we are really not dangerous.”

Even Germany and Britain, which have prosecuted some returning fighters, have left open the possibility of using techniques similar to Denmark’s. In late 2014, William Hague, Britain’s former foreign secretary, voiced support for the rehabilitation of returning fighters professing “good intentions.” Nevertheless, German security officials told The New York Times that most of the 130 ISIS fighters who had returned to Germany by late 2014 retained their radical views and planned to return to the Middle East.

“Together, we have to — and we will — prevent these people leaving to export terror,” German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere said at a meeting of his European counterparts in December 2014. “And we want to especially prevent their return as fighters to carry out attacks in Europe.”

Exaggerated fears?

Critics of hard counterterrorism approaches believe that only a limited percentage of returning Islamic fighters are sufficiently motivated to plan attacks at home. In a 2013 study titled “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” that analyzed about 1,000 fighters from earlier jihadist conflicts, Hegghammer noted that only 11 percent of the fighters returned to Europe intending to commit acts of domestic terrorism. But if that same proportion is applied to the estimated 3,000 Europeans fighting for ISIS and al-Qaida, Europe could be facing hundreds of additional terrorists.

Authors Daniel Byman and Jeremy Shapiro published an article in Foreign Affairs in late 2014 that argued that many European fighters will die in combat or gravitate to new non-European battlefields once Syria loses its allure. Those who do return to Europe will, by their use of social media, make themselves easy marks for counterterrorism forces.

The Charlie Hebdo attacks seemed to weaken Byman’s and Shapiro’s arguments. One of the French-born killers, Cherif Kouachi, was known to authorities and imprisoned in 2008 for recruiting fighters for action in Iraq. Viewed as a low security risk, Kouachi was released before completing his sentence and promptly left to train with jihadists in Yemen. The result was France’s worst terrorist attack in decades.

Nevertheless, Byman and Shapiro weren’t blind to a possibility such as the Paris shootings: “The fact that the threat presented by returning Western jihadists will be less apocalyptic than commonly assumed should not lull authorities into complacency. Terrorism is a small-number phenomenon: Even a few attackers can unleash horrific violence if they have the training and motivation.”

Conclusion

Horrors such as the Paris carnage will only intensify European governments’ efforts to pre-empt terrorist attacks by returning ISIS and al-Qaida fighters. Among the options is the deradicalization approach offered by Denmark. But judging by the criminality of more than a few returning jihadists, few countries are placing their faith in soft approaches alone.

Even in Aarhus, the radical mosque accused of recruiting young Danes for overseas jihad has come under closer scrutiny for the role it played in inspiring Muslims to join ISIS in Syria and Iraq. European security forces will continue to play a critical role in preventing violence from would-be terrorists among the ranks of returning fighters.

As Belgium thwarted a major attack on its police forces in January 2015, Europol’s Wainwright sized up the counterterrorism problem facing Europe: “The scale of the problem, the diffuse nature of the network, the scale of the people involved makes this extremely difficult for even very well-functioning counterterrorist agencies such as we have in France to stop every attack.”

Comments are closed.