Inoculating societies against propaganda

By Judith Reid, Ph.D.

The Zika virus sneaked into the United States as a stowaway in the saliva of a common mosquito. Similarly, seeds of public dissent and discord are spreading through American social media, carried by Russian trolls and bots. Negative information campaigns are not new. The tactic was used by Adolf Hitler to justify the Austrian Anschluss, and more recently by Russian President Vladimir Putin regarding the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in eastern Ukraine. How do Central and Eastern European countries keep these “mosquitos” at bay and, if bitten, develop antidotes to the toxins?

The U.S. has been under a misinformation siege for several years. The Russians manipulated public opinion through all facets of social media to influence the 2016 national elections and even the 2018 gun control debate after a mass school shooting in Florida. Ukraine’s loss of territory was preceded for years by a well-executed false information campaign.

How does society guard against this plague? Not just from large nations with a taste for territorial expansion, such as Russia, but also from smaller bands of nonstate actors with desires for power and control? Are there clues in the cultural bodies of would-be victims that could be used to repel this negative media onslaught?

This article delves into the cultural paradigms of the U.S., Russia and numerous Central and Eastern European countries to identify the vulnerabilities that can open countries to outside influences and to explain how countries can guard against disinformation attacks.

Propaganda and culture

The U.S. is perpetually open to disinformation campaigns because free speech is a key tenet of its government and society. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ensures the right of free speech for everyone. Any citizen or guest can spread truths, beliefs, rumors and fake news with relative impunity. Social media platforms now tailor news feeds according to the tracked reading habits and interests of the individual. In business, this is called micro-marketing to the individual. In public discourse, it reinforces existing opinions.

How can a country’s cultural profile, such as the core value of free speech, be used to illuminate vulnerabilities to propaganda’s bites and stings? How can understanding the cultural underpinnings of a society guide leaders to preventive measures and post-infection ointments? Propaganda mosquitos are pervasive throughout the world. How do leaders and citizens keep from getting bitten?

Hofstede’s paradigm

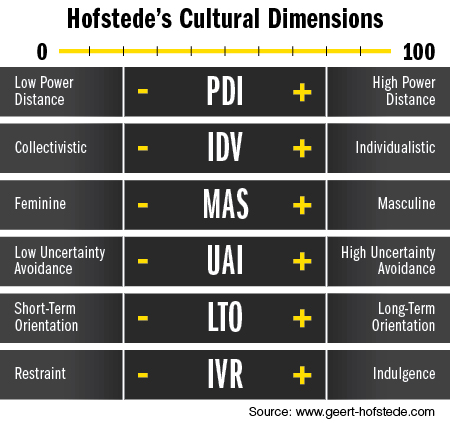

In his book, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, Geert Hofstede presents six underlying pillars of every culture: power distance index, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, uncertainty avoidance index, long-term orientation versus short-term normative orientation, and indulgence versus restraint. Whether it’s a country’s sense of nationalism, a business’s organizational culture, or a private club’s way of doing business, all established groups develop and maintain a culture that can be arrayed using these indices. Understanding these pillars for any society can illuminate potential strengths and weaknesses against foreign influences.

For example, the power distance index (PDI) highlights the use of hierarchy in a country. If a country has a rigid class system with numerous layers, then it has a high PDI. If societal layers are more fluid and the hierarchy flat, then it has low PDI. In high-PDI countries, separation between the elite and the proletariat is almost complete. Centralized management, rigid inequality and formal rules mark the world of governance. There are seemingly unending chains of superiors without decision authority, and relations between subordinate and superior are based on emotion. Might trumps right, the leaders have privilege, power and status, autocratic and oligarchic governments are based on co-optation, and the elite are protected from the consequences of scandals. Hierarchies can be deep and rigid, like military organizations, or have only a few impermeable layers, as seen in poorer countries with a small middle class. According to Hofstede, countries with a high PDI quotient include Slovakia, Russia, Romania and Serbia.

Hofstede arrays countries by their individualism versus collectivism (IDV). Countries high on the IDV index are known for their individualism, rights to privacy, merit promotion and equal treatment under the law. The U.S. and United Kingdom are two of the most individualistic countries in the world. More collectivist countries honor the group over the individual and seek harmony and consensus over self-actualization. In low-IDV groups, prevailing opinions are determined by group membership, the state plays a key role in the economic system, and rights differ by group. In these countries, relationships trump tasks, the social network is the main source of information, and people are born into families that protect them throughout life in exchange for loyalty. Countries with a high IDV quotient include Hungary, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland and the Czech Republic. Romania, Slovenia and Serbia represent countries that are more collectivist.

Hofstede arrays countries by their individualism versus collectivism (IDV). Countries high on the IDV index are known for their individualism, rights to privacy, merit promotion and equal treatment under the law. The U.S. and United Kingdom are two of the most individualistic countries in the world. More collectivist countries honor the group over the individual and seek harmony and consensus over self-actualization. In low-IDV groups, prevailing opinions are determined by group membership, the state plays a key role in the economic system, and rights differ by group. In these countries, relationships trump tasks, the social network is the main source of information, and people are born into families that protect them throughout life in exchange for loyalty. Countries with a high IDV quotient include Hungary, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland and the Czech Republic. Romania, Slovenia and Serbia represent countries that are more collectivist.

The masculinity versus femininity index (MAS) distinguishes a society’s sense of competition versus cooperation and assertiveness versus modesty. In a highly masculine society, importance is placed on earning, recognition, advancement and challenge versus a more feminine society, where the goal is to have good working relationships, a desirable living situation and employment security. In more masculine societies, gender roles are separate and distinct. Men are responsible, decisive and ambitious; women are caring, gentle and support the success of their men. In highly masculinized societies, men are subjects and women are objects, sexual harassment is an issue, and homosexuality is seen as a threat to society. In feminine government, politics is based on coalitions, government aids the needy, and international conflicts are best settled through negotiation and compromise. According to Hofstede, highly masculinized countries include Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, whereas more feminine societies include Latvia, Slovenia and Lithuania.

The uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) measures the extremes to which a society’s people will go to avoid encountering the unknown. “The evil that I know is better than the good that I don’t” could be their slogan. In high UAI countries, uncertainty is a constant threat that should be avoided. Ambiguity and unfamiliar situations cause stress, and what is different is considered dangerous. Rules and laws are important, precision and formalization are desired. There is an inherent belief in experts and technical solutions. Citizens are not interested in politics, and civil servants tend to have law degrees. There is a preponderance of precise laws and unwritten rules. Xenophobia, nationalism and protecting the “in group” are important facets of high-UAI countries. Russia, Poland, Serbia, Romania and Slovenia score high on the UAI scale. There are no low-UAI Central or Eastern European countries.

In the long-term orientation versus short-term normative orientation (LTO) scale, persistence, thrift, ordered relationships and a sense of shame are important versus reciprocation, respect for tradition, protecting face and personal stability. In high-LTO societies, work values include honesty, accountability and self-discipline. What is good or bad is situationally determined, and adaptiveness and learning are important. The focus is on market position and profits in 10 years. Countries high on the LTO scale include Ukraine, Estonia, Lithuania, Russia and Belarus.

Indulgence versus restraint (IVR) measures happiness, life control and the importance of leisure. In restrained societies, gratification is curbed and controlled by strict social norms. These societies exhibit a sense of helplessness, moral discipline, cynicism, pessimism and a lower percentage of happy people. Here, freedom of speech is not a main concern, though maintaining order is. There are no Central or Eastern European countries high on the IVR scale. Those gathered on the extremely restrained side include Latvia, Ukraine, Albania, Belarus, Lithuania, Bulgaria and Estonia.

With these six pillars of cultural paradigms, Hofstede provides clues to societal vulnerabilities and natural defenses from metaphorical tsetse flies disguised as online friends.

The U.S. versus Russia

Viewed through Hofstede’s cultural indices (and graded on a scale of 0-100) Vladimir Putin comes from an overarching culture that believes strongly in inherent hierarchy, and Putin wants to be at the top (PDI-93), which he sees as for the greater global good (IDV-39 and MAS-36). He has a strong need to control (UAI-95) and is willing to play the long game (LTO-81 and IVR-20) to achieve his vision of success. By contrast, U.S. President Donald Trump was born of a culture of flat hierarchies (PDI-40) and very high individualism (IDV-91), where anyone with a dream and enough gumption can succeed. The overarching culture of the U.S. is fairly competitive (MAS-62), risk taking (UAI-46), with little restraint (IVR-68) and very short attention spans (LTO-26).

It would be fair to suspect that Putin sees the U.S. as a very easy mark to influence through propaganda. He likely sees Americans as narcissistic children with short attention spans who can be easily hooked through social media. He can appeal to America’s sense of superiority and to its inherent optimism and future focus to undercut public messaging through a thousand mosquito-like bites on the internet. Those bites will irritate and cause some scratching, but are just enough under the pain threshold to be ignored as attention stays riveted to phones and computers, to “likes” and “shares.”

Russia’s high uncertainty avoidance was noted in a front-page article in The Washington Post titled “The Putin Generation,” in which a young journalist is quoted as saying: “What the Russian soul demands is that there be one strong politician in the country who resembles a czar.” Even though Putin controls the main television channels, the security services and the judiciary, most of the country supports him. They feel that he will stand up to U.S. aggression and that he can keep everything in balance. One 18-year-old is quoted as saying that open government corruption is upsetting, “but this is no time for an untested leader … making change could lead to the collapse of the country.”

Fake news swarms the American information space like Zika-infected mosquitos. When the U.S. finally wakes up to this danger, how much damage will have been done, and will it be possible to repel further invasion? On the positive side, the very cultural bias that can be exploited to Putin’s advantage is also the saving grace that can pull the U.S. out of the trap. IDV and IVR wrapped in patriotism and love of freedom will eventually awaken to the irritation and will resist the invasion with every antibody in its being.

European cultural frameworks

What clues can culture provide on the vulnerabilities of European countries? Germany is more like the U.S. than Russia, with a lower PDI (35), mid-IDV (67) and MAS (66) and a UAI (65) that is between the U.S. (46) and Russia (95). Both Germany and Russia are long-term oriented and more restrained than not. It would be interesting to study the profiles of Georgia and Ukraine, but there is not enough data to be of assistance in this model. Ukraine is very long-term oriented and very restrained. Georgia falls in the low- to midrange on both LTO and IVR, but the other four criteria have no data.

In another article, this author discussed the combination of high PDI and high UAI and how environments with those characteristics were ripe for dictators, because the population honored rigid hierarchies and were so averse to uncertainty as to do almost anything and suffer almost any circumstance just to know the likely outcome of any daily transaction. The countries that still have that cultural profile include Russia (PDI-93/UAI-95), Romania (PDI-90/UAI-90) and Serbia (PDI-86/UAI-92). The danger here is the acceptance by the common person that inequity is normal, coupled with the willingness to do anything to maintain the status quo. In this environment, a bully could force his way in through media or force and declare a new order with a fair chance of success.

Other countries that have a midrange PDI with high uncertainty avoidance include Croatia (PDI-73/UAI-80), Slovenia (PDI-71/UAI-88), Bulgaria (PDI-70/UAI-85) and Poland (PDI-68/UAI-93). These countries still cling to the status quo, but give less credence to a rigid hierarchy. Collectivism is the norm in Croatia (IDV-33), Slovenia (IDV-27) and Bulgaria (IDV-30), with Poland more individualistic (IDV-60). What this means in terms of an aggressive, negative strategic communications plan is that outside forces would want to target elements of uncertainty avoidance. How could outsiders upset the sense of predictability to make segments of a population cling to malicious messages? They would not have the advantage of high PDI, meaning a recognition that rigid hierarchy is normal, so the combination of high uncertainty avoidance (the world as we know it is changing fast) with high collectivism (and we are all in it together) would be the key approach to propaganda — less “strong man” and more “every man is in danger.”

Hungary has an interesting profile. It shows a midrange PDI (46), high individualism (80), high masculine (88) and high uncertainty avoidance (82). Its long-term orientation (58) and indulgence (31) are both midrange. With high IDV, MAS and UAI, it is vulnerable to messages of inadequacies of the male ego.

Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia each have low PDI scores (44, 42, 40) and midrange uncertainty avoidance (63, 65, 60), but they vary some in individualism (70, 60, 60) and in masculinity (9, 19, 30). A low PDI and midrange UAI would signal that negative messaging should address a general sense of unease and exploit an uncertainty that is common to most people within these countries, such as a sense of safety or scarcity.

Cultural vulnerabilities are most often opaque within one’s own society, which can easily make a simple walk through the woods become a dengue-infected nip on the neck.

Outsider cultural clues

At its root, propaganda is an exaggeration of collective emotions, Jason Stanley writes in his book, How Propaganda Works. How does an outsider pull emotional strings inside another country?

Time orientation: Cultures are oriented to the past, present or future, according to work by anthropologist Edward T. Hall. Leaders should pay attention to outside messages that pull public emotions into the time orientation that corresponds to the culture at risk. In Venezuela, Hugo Chávez’s method of gaining the middle-age vote was to conjure up a past when the government was “mired in corruption, incompetence, and poor management,” William J. Dobson writes in The Dictator’s Learning Curve: Inside the Global Battle for Democracy.

Rational language: According to Stanley, language is a mechanism that allows negative strategic messaging to work. It presents an idea as rational, when upon closer examination, it is not. The negative statement is not exactly lying; rather it presents an element of truth while encouraging the reader to fill in the details to create an emotional message that can override rational judgment. For example, shortly after the mass shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, online stories claimed that some victims were really “crisis actors,” and Russian bots engaged in the gun control debate to sow chaos and confusion.

Over simplification: In Red Scared!: The Commie Menace in Propaganda and Popular Culture, Michael Barson and Steven Heller note that “propaganda is based on the creation of recognizable stereotypes that oversimplify complex issues for the purpose of controlling mass opinion.” Using this approach, the U.S. government encouraged anti-communist “red-baiting” in the media during the Cold War.

Snowball conspiracy: Lisa-Maria Neudert of the Oxford Internet Institute’s computational propaganda project notes that Facebook’s and Google’s advertising technologies target specific groups and individuals with misleading and conspiratorial content since that content generates the most engagement and keeps readers “on the page,” a key metric used by social media companies. Guillaume Chaslot, a former Google engineer, says the algorithms used in social media are designed to keep people engaged. For example, a conspiracy video that is favored by the algorithm encourages others to upload similar videos corroborating the conspiracy, which increases the retention statistics and continues the snowball effect until the conspiracy appears to be somewhat credible. This creates what Neudert calls an “environment that maximizes for outrage.”

Like the West Nile virus hijacking a ride on a mosquito, outside agents can ride in on a hot summer evening to infect the information flow within any country.

Reinforcing authoritarian rule

Fear is the emotional tool of choice for dictators to control their populations through strategic messaging. Chávez’s leadership provides useful insights into the use of fear as reflected in Venezuela’s uncertainty avoidance.

Chaos and division: After Chávez won the support of the general population in Venezuela, he championed chaos and division. He disallowed dissent, calling those who questioned his brand of revolution “traitors, criminals, oligarchs, mafia, and lackeys of the United States. Although he originally promised to break the political parties in order to return power to the people, Chavez … centralized nearly all power in his own hands,” Dobson writes.

Fear: María Corina Machado, co-founder of a Venezuelan election watchdog group, noted that Venezuelans did not believe their ballots were secret. About 5.6 million Venezuelans depended on government income and believed that their votes could be seen by the government, so they perpetuated the public adoration of Chávez to protect their livelihood. As Machado notes in Dobson’s book, “Fear does not leave fingerprints. … It has been Chávez’s biggest and best-used instrument from day one.”

Uncertainty: In 2009, Chávez closed 34 radio stations for supposed administrative infractions and announced it was investigating hundreds more. The government never identified the other stations under investigation, which kept the entire industry in check. In this way, Dobson notes, the media could exist, but the content was self-censored by those very radio stations for fear of retaliation.

Political apathy: According to Dobson, “Widespread political apathy is the grease that helps any authoritarian system hum. And in the smoothest-functioning authoritarian systems, the regimes have gone to great lengths to turn disinterest in political life into a public virtue.”

Like the insidious Anopheles mosquito, the risk of “informational malaria” is constantly looming in the background.

Protecting society

How can a nation inoculate itself to the effects of fake news or negative messaging campaigns?

Open discussion: Free and open discourse in the public arena is key to uncovering fake news and other messages streaming into online and public consciousness. People should counter political apathy by discussing current events with a wide variety of other people with differing views.

Freedom of the press: News and information feeds should remain free of bias and come from many differing viewpoints. An independent media is essential for exposing wrongs, conspiracies and corruption. Free TV and public media help disseminate a wide variety of political and social viewpoints.

Critical thinking: According to Stanley, “the antidote is to retain a core of critical thinking, to question emotional messages and to fact check anything that smacks of fake news. Deconstruct the message to uncover the fixed truth (assumed) versus the variable that takes the message into falsehood. Think of what facts are omitted, ponder the inverse of the message. Reset the conversation to focus it appropriately.”

Humor: In Chávez’s Venezuela, the opposition created a public communications campaign featuring a farcical Miss Venezuela, who refused to give up her crown and was now old and ugly, as a way to suggest that Chávez should relinquish his position. As Dobson notes, humor undermines the other’s authority and is the best cure against fear.

Open discussion, freedom of the press, critical thinking and humor have roots in the cultural paradigms of power distance, individualism and uncertainty avoidance. Studying how these cultural elements impact an open society can illuminate key antidotes to protect countries against the scourge of fake images and fake news.

Conclusion

Information warfare is widespread throughout the world. Those who cultivate it and release the swarms of propaganda against other nations have studied the cultural vulnerabilities of their targets. They use emotional language, irrational logic, oversimplification and snowball conspiracy to soften their enemy’s defenses. To keep from getting bitten or infected, Central European leaders and citizens should encourage open discussion, freedom of the press, critical thinking and humor.

Comments are closed.