The Consequences of COVID-19 in the Post-Soviet Space

By Dr. Pál Dunay, Marshall Center professor | Photos by The Associated Press

The coronavirus that dominated the 2020 agenda and continues to have major influence in 2021 caused the loss of millions of human lives, resulted in the loss of national incomes and in some cases contributed to political instability. It has noticeably contributed to the ongoing adjustment of power relations among the most influential states in the world. This article looks at the consequences of COVID-19 and the way 12 states that were once constituent republics of the Soviet Union bore its burden and reacted to the challenge. It considers the medical situation while it focuses on the socioeconomic and political consequences, with an emphasis on similarities and dissimilarities.

Pandemic With Regional Particularities

Thirty years have passed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, an “amalgamated” community of putative republics with no sovereignty. But belonging to the Soviet state also meant there were certain standards that the republics could benefit from and that have residual relevance for the COVID-19 pandemic. Among them:

- Although the Soviet health care system was not the most modern or the best organized, it was large and provided basic treatment on a standard level. Medical education was of fairly high quality. The post-Soviet republics lost some of these advantages. However, the fact that most of them did not modernize their health services or rely on shorter, technology-based treatments, such as one-day surgeries or other outpatient treatments, meant that many had a fairly high number of hospital beds available when the pandemic hit, with Belarus, Ukraine and Russia having the most (10.8, 7.5 and 7.1 beds per thousand inhabitants, respectively). The number of medical doctors per thousand inhabitants presented a different picture, with Georgia, Belarus and Armenia having the most

(7.1, 5.2 and 4.4 per thousand, respectively). - The use in the Soviet Union of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine against tuberculosis seems to provide some protection. In July 2020, medical science recognized a possible link between that vaccine and a reduction in severe COVID-19 cases, particularly in the elderly. BCG vaccinations continue to be mandatory in every former Soviet republic with reported cases, sending a message to vaccination skeptics.

- The average life expectancy in the post-Soviet space is shorter than in more developed countries. On a list of 174 countries, the 12 states are ranked in life expectancy between a high of 81 (Armenia) and a low of 129 (Turkmenistan). Russia is 111th on the list, with a female life expectancy of 77.6 and a male life expectancy of 68.2 years. This means that the older generation represents a smaller portion of the population in the former Soviet region than in Western Europe, North America or Japan. Because of that, fewer older people were exposed to a pandemic that hit the elderly more severely than other population groups.

- The post-Soviet republics inherited a high degree of civil obedience that was maintained by various authoritarian regimes following the breakup. Whether people followed the rules voluntarily or because they saw no alternative is of secondary importance for this analysis.

- A low level of trust in the health services in much of the post-Soviet space conversely has been a contributing factor to the lower number of recorded fatalities. People knew that going to the hospital meant putting their lives in the care of a health service that may be unable to guarantee their survival.

Socioeconomic Consequences of the Pandemic

Most states in the former Soviet space reacted similarly to the pandemic. They recognized that the situation was severe, cut international travel to a minimum, reduced human contact, closed schools and universities, banned cultural and sports programs, and requested that people keep distance from each other and not hold large gatherings, like weddings. Lockdowns were introduced and testing slowly started. Nine of 12 states followed mainstream solutions adopted by countries across the world. It is impossible to address each of the 12 states individually in the given framework here, so only a few are highlighted. Russia’s multifold, although eroding, centrality in the post-Soviet space, and the fact that its gross domestic product (GDP) represents more than half of the region’s total, requires that the presentation start there.

With its many hospital beds and large strata of medical professionals, Russia was well positioned to address COVID-19. However, it quickly became clear that the specialized knowledge necessary to treat COVID-19 patients was concentrated in a few population centers. To address the pandemic in other places, new hospitals had to be built at a rapid pace. Russia’s economy appeared to be relatively resilient to the effects of the pandemic and lockdown in the first half of 2020. It had a budget surplus, foreign reserves of $592 billion and a sovereign wealth fund amounting to $174 billion. In addition, Russia had planned its budget based on an oil price of $42 per barrel and oil prices were somewhat higher during most of the second half of 2020. However, the Kremlin still faced a decision. It wanted to avoid a depletion of its financial reserves that would potentially expose it to pressure from the West. Therefore, it allocated only 2.8% of GDP to an emergency aid package for the public. Only 3% of this package was designated to support small- and medium-size businesses and workers, according to Russian political scientist Lilia Shevtsova. Russian President Vladimir Putin made some minor attempts to redistribute the financial burden by ending a flat income tax rate and increasing the tax rate for the highest earners, from 13% to 15%. However, these are regarded as little more than a cosmetic demonstration of solidarity.

Russia wanted to avoid a second lockdown in the fall of 2020. It had left some production sites open even during the worst moments of the pandemic. Oil and gas production and diamond mining (the latter representing 28% of the world’s production) never stopped, illustrating Russia’s intention to guarantee a continuing inflow of cash. Diamond mining stands out because production was suspended everywhere else in the world, which helped Russia’s profits. Although Russia’s economy contracted in 2020, it was only about minus 4%, a reassuring result when compared internationally. It is clear that Russia can preserve a sustainable economy. However, it will be sustainability with a relatively low economic growth rate (projected at 2.8% in 2021) that will make some highly ambitious development plans impossible to realize.

A closer look at Russia’s performance during the first year of the pandemic finds mixed results. Russia followed mainstream solutions enacted elsewhere in the world. It introduced a six-week lockdown between late March and mid-May 2020, when 30% of its labor force was teleworking. It increased the number of hospital beds with ventilators (reaching 31,000). Federal health care spending increased by approximately $13 billion. Following a very difficult period in late autumn and early winter 2020, the occupancy of hospital beds was reduced to 69.2%, according to official Russian sources. Russia also introduced a tax exemption for medical products.

The Russian Federation performed poorly in two areas: First, it did not support small- and medium-size enterprises sufficiently, which resulted in the closing of 1.1 million companies. However, the government opened a centralized digital website (Opora Rossii) to help those small-business owners, and there is reason to assume that at least some of those companies will reopen. Second, and more worrying for Russia, is that foreign direct investment (FDI) nearly collapsed in 2020. Whereas the inflow of FDI reached $31.7 billion in 2019 (a massive increase from $13 billion in 2018), it was reduced to $1.2 billion in the first half of 2020 (compared to $16 billion in the first half of 2018). Because of that, Russia should consider the economic consequences of its political decisions.

Georgia is perhaps the country that has moved furthest from the old Soviet mentality in the 21st century. It is one of few countries praised by the United Nations for its fight against COVID-19. Georgia’s success is attributed to the strategy taken by its medical experts. Georgian experts, aware of the weaknesses in the health care system, realized that the country lacked sufficient equipment and personnel to deal with the pandemic. They decided to slow the spread of the disease in a strict, immediate and systematic manner, employing three main tactics. First, Georgia quickly canceled all flights to and from China and introduced strict measures to identify, track and quarantine travelers, particularly those from severely affected countries. The government also benefited from having modern biological laboratories to conduct rapid testing. Second, all schools were closed, gatherings of more than three people were banned, a night curfew was imposed and nonessential businesses locked down. The government took those measures at the expense of the economy. In the end, its GDP contracted by 5% in 2020. Third, the authorities held a massive information campaign to convince people to stay at home and comply with restrictions. Although in the end, the country reported more than 3,000 deaths in 10 months, the way it addressed the public made the country distinctly different from other post-Soviet states.

In Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko made pronouncements true to the image he has always intended to project, that of a macho man. His advice on how to fight COVID-19 was extremely simple: He characterized the pandemic as a “psychosis,” and went so far as to suggest remedies such as “drinking vodka, taking saunas and playing ice hockey.” Lukashenko’s rhetoric aside, the reality of Belarus’ reaction was more complex. Belarus benefited from a high number of hospital beds. In addition, unlike in several other former Soviet states, the quality of the medical personnel was largely preserved after the Soviet breakup.

Belarus, with a population of 9.5 million, conducted nearly 4.26 million COVID-19 tests between May 2020 and January 2021. Although more than 236,000 people were infected, about 221,000 recovered. The number of fatalities remained below 1,700, according to the country’s official numbers. Instead of a lockdown, the country’s Ministry of Health issued recommendations for COVID-19 prevention and physical distancing. Despite the president’s pronouncements, it appears that Belarus successfully addressed the health hazards of COVID-19.

The broader economic, social and international repercussions were more mixed for Belarus. Because the country attempted to weather the pandemic without a lockdown, Western countries warned against travel to and from Belarus. Russia, the country’s most important neighbor, closed its border between March and July. A gradual easing of the restrictions helped to relieve the economic impact in crucial areas, like the Russian-built nuclear power plant in Belarus that was put into operation during this period. Lukashenko claimed there were three factors that contributed to the economic difficulties: first, the relatively low price of crude oil and the declining demand for Belarusian oil products due to the contraction of the world market; second, the cost of treating COVID-19 patients; and third, the rallies protesting his presidential election. It is evident that Belarus used COVID-19 as an excuse for its existing economic malaise. The coexistence of factors, including the decadelong economic stagnation, the rapid decline of political support for Lukashenko, and a rejection by many of the “socialist/communist” political model, is an indication that the times of heated political tension are far from over.

In 2020, Russia provided Belarus with a $500 million loan and also forgave $1 billion of debt. This helped Belarus regain stability during protests against Lukashenko and demonstrated Russia’s support of Belarus. During the COVID-19 crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided Belarus with $90 million. However, a much larger support package in the range of $940 million was not agreed upon because the IMF required quarantine, isolation and curfew measures. Lukashenko called the conditions unacceptable. The European Union allocated funds to Eastern Partnership states, including 60 million euros for Belarus, with a reminder of the benefits of bilateral cross-border cooperation with neighboring EU member states.

Tajikistan did not immediately recognize the pandemic’s challenges and took only partial measures. Tajik citizens were evacuated from Wuhan, and Chinese citizens in Tajikistan were monitored medically and later quarantined. It was apparent the Tajik health services would have been overmatched had COVID-19 reached the country on a large scale. Tajikistan published very low infection numbers, identifying many as suffering from pneumonia and dying because of illnesses other than COVID-19.

Tajikistan has among the lowest per capita GDP among former Soviet republics. Some population segments suffer from malnutrition and the country had to rely on help with basic commodities, including 6,000 tons of wheat flour (5,000 from Kazakhstan, 1,000 from Uzbekistan). When taking a closer look at the assistance Tajikistan received, it becomes clear that its partners, including China, Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and German nongovernmental organizations, such as Caritas Germany, preferred to provide masks, gowns, ventilators, testing kits and other medical support rather than provide financial assistance. This is understandable when considering the level of corruption and the political system. Even the IMF limited its emergency financing to $240 million, the equivalent of the IMF’s quota for Tajikistan and a relatively small sum.

Tajikistan’s heavy dependence on remittances from its migrant laborers aggravated the economic situation, especially when Russian firms laid off Tajik gastarbeiters (guest workers). The situation became so severe that the Tajik ambassador to Russia requested that large companies discontinue the practice because the missing remittances were a burden on the troubled economy.

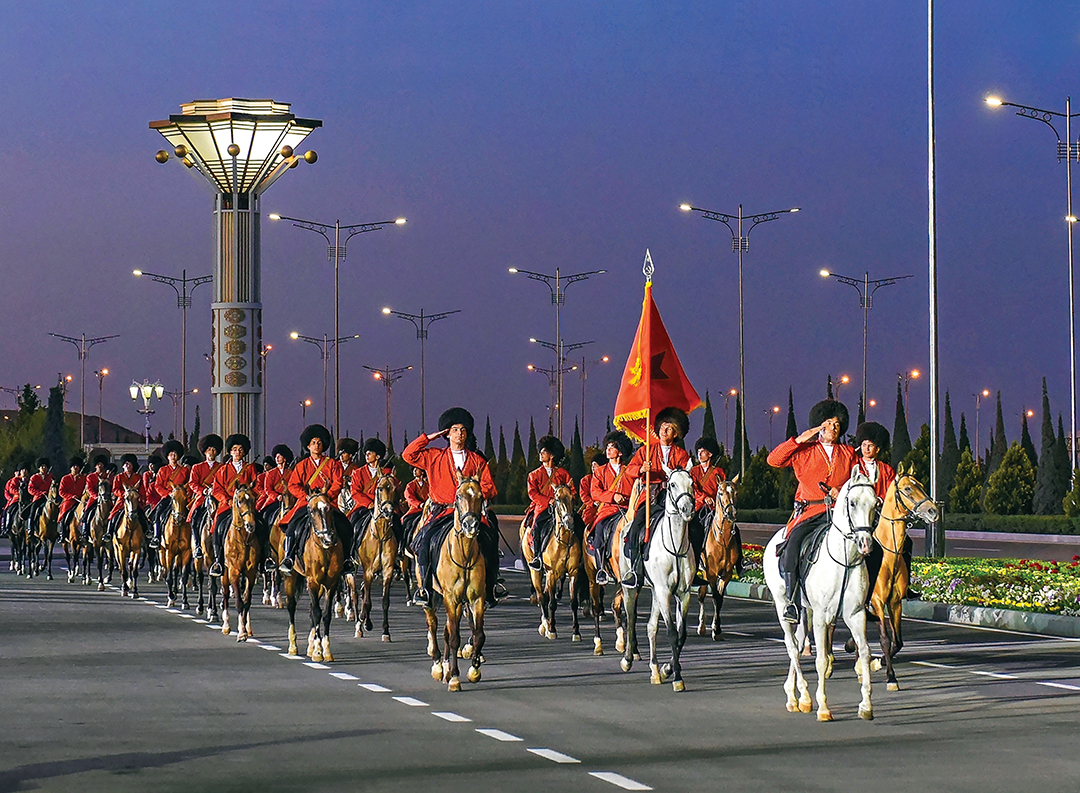

Turkmenistan did not adopt the preventive measures accepted by many other countries. Although Ashgabat suspended all flights to and from China and Thailand, and then denied entry to foreigners infected by COVID-19, no other measures were taken. A distinguishing feature of Turkmenistan’s response is banning the term coronavirus. At the same time, President Gurbanguly Berdymuhamedov, a dentist by training, recommended that people use traditional medical methods to treat the virus, such as the burning of an herb, claiming it could kill viruses “invisible to the naked eye.” So confident were the Turkmenistani authorities, and so farcical their pandemic denialism, that 3,500 people gathered to celebrate World Health Day in April 2020 without taking precautionary measures against the spread of the disease.

The authorities established a team of medical experts to prevent an outbreak, with a focus on schools. Near the end of April 2020, the country’s minister of foreign affairs claimed there were no COVID-19 cases in Turkmenistan. By mid-June, however, reports began to appear in social media about confirmed cases and later that month Human Rights Watch accused the government of “jeopardizing public health by denying an apparent outbreak of the coronavirus.” Also that month, the U.S. Embassy in Turkmenistan said that citizens with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 were being placed in quarantine in infectious diseases hospitals, despite government claims to the contrary. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by accusing the U.S. Embassy of spreading “fake news.”

In July 2020, an official World Health Organization (WHO) mission arrived in Turkmenistan and later urged the government to adopt “measures as if COVID-19 were circulating,” to “fully investigate cases of acute respiratory infections and to step up testing for suspected cases of COVID-19.” This was an extremely diplomatic way for the WHO to express its concerns. The government’s denials, its refusal to provide the WHO with data, and its haphazard approach in countering the virus could have disastrous consequences for the country. Even into January 2021, no COVID-19 cases and deaths were reported by the government, meaning there is no way to adequately ascertain reality.

International Cooperation, Vaccine Diplomacy

During a pandemic, it is understandable that countries would put their own people first and use their capacities domestically. After states are sufficiently reassured that they can cope with the domestic emergency, they then can reach out to others and offer support. However, Russia did not follow that sequence. As part of its recognition-seeking activities, Russia sent a highly publicized team to support anti-COVID-19 efforts in northwest Italy, where health and sanitary services were overwhelmed. But it was not the indispensable support Italy needed. The Russian team mainly engaged in cleaning and sanitizing social institutions and elderly homes. Nonetheless, it was a major public relations success for Russia that also drew attention to the EU’s initial reluctance to help Italy.

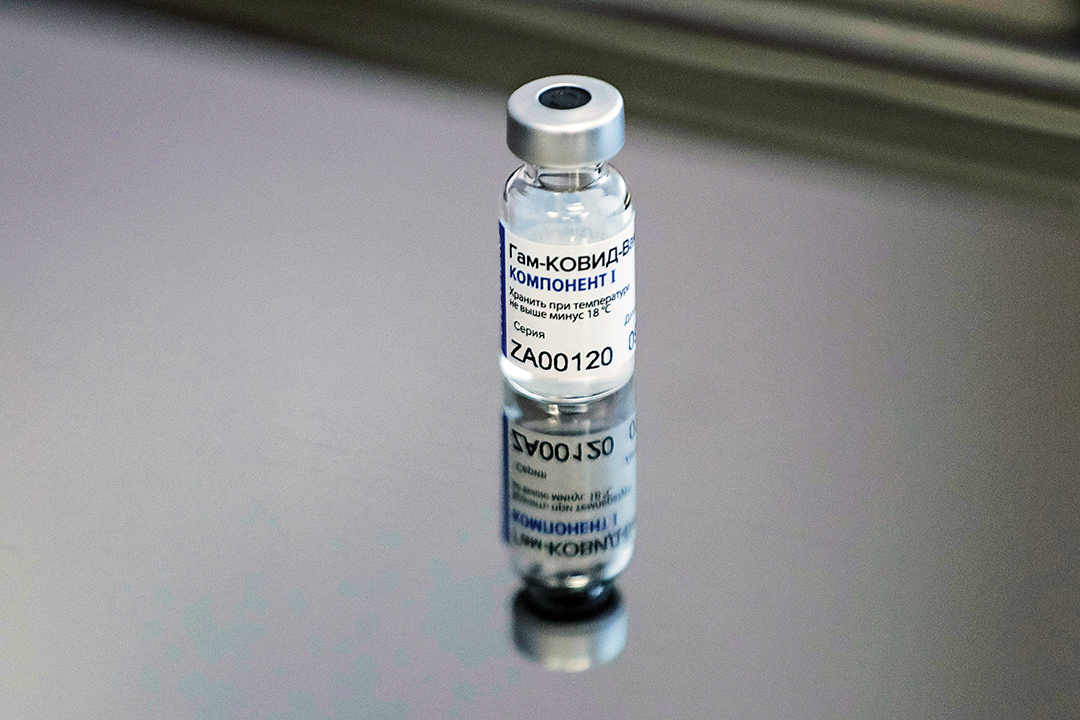

Russia then turned its attention to its own medical emergency. In the summer of 2020, Russia reached out to former Soviet republics with offers of assistance in an effort to keep its influence in the region. A number of former Soviet republics had turned to other actors, including global and regional international financial institutions such as the IMF or the Asian Development Bank, and states such as China and the U.S. The EU also contributed assistance to its six eastern partners and to a lesser extent to the Central Asian states. The Russian support included deliveries of masks, gowns and visits by expert teams to some Central Asian countries. Kazakhstan also announced that it was ready to purchase and produce the Russian-produced Sputnik V vaccine.

Russia was the first state to declare that it had invented a vaccine against COVID-19. But Putin’s announcement in August 2020 was apparently premature and was not followed by the registration of the vaccine in Russia or beyond its borders. However, because Putin made the announcement, there was no way to take it back. It is clear there were disagreements inside the Russian leadership about making the announcement without proper testing, which eroded confidence among the pubic and other states. Months passed before vaccinations started in December 2020, and they weren’t extended to the entire eligible population until mid-January 2021. Russia wanted to sell the vaccine globally, but that was only partly successful for a variety of reasons:

- The first two trial phases were done without a placebo being administered.

- The approval was granted before the vaccine had gone through a third trial and there were no published results of the earlier trials.

- Months separated Putin’s announcement and the availability of the vaccine.

- Timely delivery could not be guaranteed due to production problems.

When taking a closer look at Russia’s effort to be competitive with its vaccine, the reasons for its partial failure are clear and manifold:

- It did not follow universally established medical procedures.

- It did not have an adequate communication strategy to dispel concerns reported in the international media.

- It did not take into account that many people doubt the quality of Russian products.

- It did not sufficiently consider that it was entering a highly competitive environment.

By January 2021, 13 states had agreed to buy the vaccine from Russia or produce it under license. They included three former Soviet republics (Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), and a number of Latin American, Asian and African countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Egypt, India, Mexico, Nepal, South Korea with only local production under license for export, Serbia and Venezuela). Negotiations continued with other states that included Turkey, an important target for Russia.

One EU member state, Hungary, bought the vaccine. Hungary expressed its dissatisfaction with the speed of the delivery of vaccines produced in the West and ordered 2 million doses of Sputnik V. However, according to surveys, at the time only 6% of the Hungarian population was ready to be vaccinated by Sputnik V (the survey showed 52% for Pfizer-BioNTech and 26% for Moderna). And the so-called emergency use permission issued by Hungarian authorities was based not on Hungarian tests, but on data supplied by Russian institutions reporting interim results of phase-3 testing. The door probably opened for a wider acceptance of Sputnik V after a report in February 2021 in The Lancet, a reputable medical journal. Russian experts reported that phase-3 trials showed the vaccine was safe and 91.6% effective. The first Sputnik V doses arrived in Hungary that month. Although it was somewhat less trusted by the public than Western-made vaccines — be it Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna or AstraZeneca — it was more trusted than the Chinese vaccine Hungary had ordered in large quantities.

Sputnik V also caused controversy in countries considered unlikely customers, such as Ukraine. It was highly unlikely that Kyiv would purchase Sputnik V. However, the second largest political party in the Ukrainian Parliament, the pro-Russian Opposition Platform – For Life, used the opportunity to drive a wedge into Ukrainian society. Viktor Medvedchuk, its most visible leader, paid a high-profile visit to Russia, including meetings with Putin and those involved in the development, production and marketing of Sputnik V. Upon his return, he announced that Russia was ready to sell Sputnik V to Ukraine. The Ministry of Health declined the vaccine’s registration with reference to its incomplete phase-3 testing. But the effort fit into Moscow’s attempts to demonstrate that, unlike the West, it was willing to help Ukraine. The matter took a sudden turn in February 2021 when Ukraine’s government effectively banned the Sputnik V vaccine and President Volodymyr Zelenskiy approved a decision by the National Security Defense Council to take the pro-Russian television channels ZIK, 112 Ukraine and NewsOne off the air, citing the hybrid war Russia is waging against Ukraine.

Economic Recovery

Every man-made or natural disaster is followed by an economic recovery. According to economists, deferred demand by the public for goods and services and a need for reconstruction after wars and major natural disasters can spur recovery. However, the severity and longevity of a crisis make a huge difference. If a second wave of COVID-19 is not as severe as predicted, economists can envision what is known as a V-shaped recovery, one that rebounds quickly. A more severe second wave would give way to the expectation of a recovery in the shape of the Nike swoosh logo (a slowing recovery, after an initial sharp upturn) or a W-shaped recovery that indicates a contraction.

Yet another possibility is a K-shaped recovery, with some sectors recovering more quickly than others. This is a realistic scenario after COVID-19, considering that some sectors will suffer for longer periods, such as the hospitality industry, and air, rail and bus transportation. However, the post-Soviet republics are not particularly exposed to contractions in the hospitality industry; some are among the world’s least visited countries. Therefore, if vaccinations prove effective, there is a fair chance that the IMF’s prediction will prove correct and that economic contractions in nine former republics in 2020 will be followed by GDP growth in 2021 in each of the 12 states.

In some of the former republics, economic recovery is also dependent on the recoveries of other countries, first and foremost Russia. Recovery in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and to a lesser extent Armenia and Moldova, depend on Russia accepting migrant labor from those countries. There is good news in this respect because Putin, in early 2021, tasked the government to facilitate the entry of citizens from countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States to work in the construction sector. This return of cheap labor counteracts the growing distance between Russian society and the societies of former Soviet republics.

Conclusions

Most former Soviet republics adopted the same methods to contain the pandemic that were adopted across the world. The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with instability in a number of states, including Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan. However, dissatisfaction with the management of the pandemic did not appear to contribute to that instability.

The economies of the 12 states coped with the challenge, although their responses demonstrated the limits of their capacity to provide support to society’s most severely challenged strata and to small- and medium-size enterprises. In some cases, this will contribute to further divisions and increase poverty. Although labor migration was interrupted for some time, that only caused problems for those states where migrant revenues form a large portion of the GDP. Due to the severe labor shortage in certain sectors of the Russian economy, a return to the pre-pandemic pattern can be expected.

International cooperation somewhat alleviated the socioeconomic problems that stemmed from the pandemic. Understandably, that cooperation did not play a decisive role in the pandemic’s management. Russia helped some of its partners to demonstrate its primus inter pares (first among equals) role among the post-Soviet states. However, it is clear that its resources could not make a fundamental difference and could not sufficiently counterbalance the centripetal tendencies among the 12 states.

Comments are closed.