NATO and Nontraditional Security Challenges

By Michael Rühle

This observation by U.S. inventor Charles F. Kettering perfectly captures the logic of seeking to prepare for the future. Security policies are not exempt from this logic. Traditional notions of military security, which are state-centric and focused on the defense of borders and territory against aggression by another state, are increasingly giving way to a complex mix of military and nonmilitary threats that can also affect societies from within. They range from targeted man-made threats, such as cyber attacks or the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, to broader phenomena, such as climate change or resource scarcity. For NATO, which is based on traditional notions of deterrence and defense against armed attack, and whose founding treaty even defines the specific territory that is eligible for collective protection, the rise of deterritorialized, nonkinetic threats creates a whole series of challenges. How well NATO addresses them will determine its future as an effective security provider for almost 1 billion citizens.

Traditional and nontraditional challenges

The return of great power competition, notably Russia’s revisionism and China’s more assertive foreign policy, is a stark reminder that the increase of nontraditional threats does not spell the obsolescence of traditional security challenges. On the contrary, traditional and nontraditional threats increasingly interact. Cyber attacks, for example, have long been a tool for industrial espionage, yet they have also become integral to military campaigns. Similarly, while the effect of politically motivated terrorist attacks against critical energy infrastructure may be largely symbolic, state-sponsored attacks could also have the goal of undermining a country’s ability to build a coherent conventional military defense. Disinformation can be used as a tool to destabilize a state, yet it can also be part of a hybrid warfare approach, to prepare for (and then mask) direct military aggression against a neighboring state. Climate change, in turn, can increase the number and scale of natural disasters — with the military often being the first responder — but it can also aggravate conflicts between states or generate new migration pressures. Finally, the number of virtual nuclear weapons states is growing due to more countries mastering the full nuclear fuel cycle and the commercialization of proliferation — the emergence of a black market for sensitive technologies.

The limits of deterrence

Throughout the Cold War, NATO’s central paradigm was deterrence. The logic of avoiding military conflict by demonstrating that one’s own military power was congenial to that period’s specific characteristics: a single, visible enemy, symmetrical military capabilities, long warning times and, above all, the assumption that the opponent would be guided by a rational cost-benefit calculus. While deterrence remains a major concept in interstate relations, nontraditional challenges such as terrorism, cyber attacks and humanitarian disasters lie outside the deterrence paradigm. Unlike traditional military deterrence, which rests on the visibility of one’s military arsenal, cyber capabilities are kept hidden. Moreover, since cyber attacks or energy cutoffs may be deliberately designed to avoid casualties, such actions will be difficult to deter because the aggressor may hope to stay beneath the victim’s threshold for a resolute response. Other challenges, such as energy vulnerabilities or climate change, do not lend themselves at all to the deterrence paradigm. Hence, NATO must maintain the deterrence logic in its relationship to Russia and other potential competitors, while acknowledging that deterrence has little relevance beyond the traditional military context.

NATO’s approach

This emerging security landscape challenges NATO on several levels. On the institutional level, the new threats challenge the centrality of NATO because many of them are nonmilitary in nature and thus do not lend themselves to purely military responses. On the political level, the fact that these threats offer little or no early warning, are often anonymous as well as ambiguous, and above all nonexistential, creates dilemmas of attribution, solidarity and collective response. Consequently, NATO needs not only to grasp the specific character of such nontraditional challenges, but also define its role in each of them. At the same time, NATO needs to develop trustful ties with the broader community of stakeholders. To succeed in this approach, NATO must:

Overcome the mandate-means mismatch. NATO had been addressing a range of emerging threats for quite some time, yet it had done so in a compartmentalized way, without clear-cut political guidance or a thorough conceptual underpinning. The 2010 Strategic Concept, which gave considerable prominence to emerging challenges, signaled a change by providing NATO with a wide-ranging mandate to address these challenges in a more systematic way. Moreover, the creation of the Emerging Security Challenges Division in NATO’s International Staff, which happened in conjunction with the release of the Strategic Concept, created a bureaucratic foothold for nontraditional challenges within the organization, facilitating more coherent policy development and implementation in these areas.

Improve situational awareness. By bringing together over 60 intelligence services, NATO provides a unique forum for discussing current and future threats, including nontraditional ones. Intelligence sharing in NATO includes all developments that are relevant to allied security, ranging from regional conflicts to attacks on critical energy infrastructure. To further enhance situational awareness, NATO created an Intelligence Security Division in its International Staff, while at the same time expanding its in-house analytical capabilities. In contrast to intelligence sharing, strategic analysis allows for a more forward-looking and sometimes more provocative open-source approach toward emerging challenges, ranging from the security implications of artificial intelligence to the strategic consequences of bitcoin.

Manage the attribution challenge. The attribution problem is another area that sets nontraditional challenges, such as cyber attacks, apart from traditional forms of conflict. While the perpetrator of a traditional military attack is usually identifiable (even terrorist nonstate actors like to brag about their deeds), cyber is much more ambiguous. Even if the defender were certain about the attacker’s identity and sought to “name and shame” the perpetrator, he would find it difficult to marshal evidence of a kind that the international community would consider convincing. Moreover, traditional weapons, such as tanks and fighter jets, are owned by states. By contrast, cyber capabilities and other disruptive means are owned mostly by the private sector and even by individuals. If the threat of attribution is to act as a deterrent, the allies will need to settle for less-than-perfect evidence as sufficient to hold a perpetrator publicly responsible.

Enhance training and education. The growing importance of nontraditional challenges is making them a permanent subject of NATO’s education and training programs. Diplomats and military leaders alike must be given the opportunity to develop a better understanding of cyber, energy, climate change and similar challenges as drivers of future security developments. To this end, dedicated courses have been set up at NATO’s training facilities as well as the NATO Centres of Excellence, and existing courses are being augmented. Given the specialized nature of some nontraditional challenges, notably cyber, NATO must offer courses suitable for subject matter experts, but also needs to invest in strategic awareness courses focusing on the broader picture.

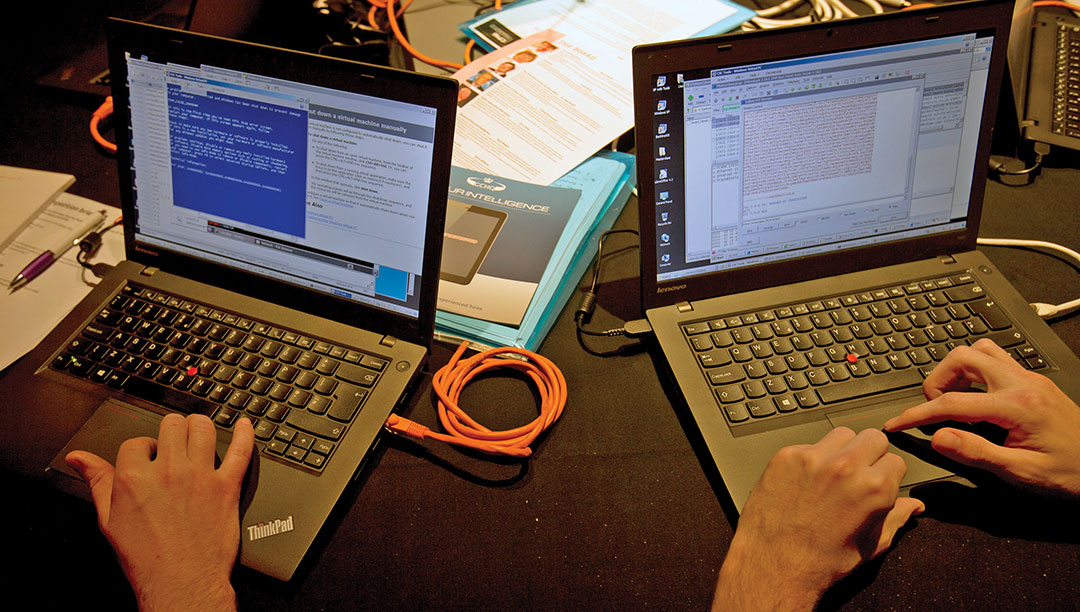

Adapt NATO exercises. The challenge of coping with nontraditional threats is also increasingly reflected in NATO’s exercises. Even a “traditional” military conflict today will include numerous cyber elements, the targeting of energy and other critical infrastructure, and massive amounts of disinformation. Hence, it is only through exercises that the effects of these nontraditional threats can be understood. The integration of nontraditional challenges in NATO’s exercises reflects an awareness of this fact, as does the more frequent use of tabletop exercises, which allow for a more granular approach to specific challenges. For example, the NATO Energy Security Centre of Excellence conducted such an exercise with Ukraine in 2017 and contributed to a report about Ukraine’s electricity network.

Enhance resilience. Assuming that certain types of attacks, such as cyber or terrorist, will happen and cannot be deterred, the focus needs to shift toward resilience. Since cyber attacks are happening with increased frequency, the emphasis must be placed on upgrading defenses so that networks will continue to operate in a degraded environment. Similarly, the effects of attacks on energy infrastructure can be minimized if that infrastructure can be repaired quickly. Such resilience measures are largely a national responsibility. However, NATO can assist nations in conducting self-assessments that help identify gaps. This new focus on resilience is also important for NATO’s traditional collective defense: an opponent seeking to undermine NATO’s collective defense preparations will do so first and foremost by nontraditional, nonkinetic means, such as cyber attacks or energy supply disruptions.

Develop links with other international organizations. The nature of nontraditional security challenges makes NATO’s success increasingly dependent on how well it cooperates with others. Consequently, NATO needs to be much better connected to the broader international community. This is true for its relations with other security stakeholders such as the European Union and the United Nations, but also with respect to nongovernmental organizations. Hence, enhancing NATO’s connectivity is a precondition for its future as a viable security provider. The NATO-EU relationship, which is perhaps the most important of all, has seen considerable progress, notably due to both organizations’ vocation to address nontraditional security challenges. Since many of these challenges are both internal and external in nature, cooperation between NATO and the EU is the sine qua non for any pragmatic approach to meeting them.

Develop links with the private sector. Another part of a better-connected NATO is a sustained relationship with the private sector. Just as the urgency to enhance NATO’s cyber defense capabilities is leading to closer ties with software companies, the need to develop a more coherent approach to energy security will require NATO to reach out to energy companies. With most energy and cyber networks in private hands, it will be crucial to build public-private partnerships. The goal should be to establish communities of trust in which different stakeholders can share confidential information on cyber attacks and other security concerns. Creating such new relationships will be challenging, since national business interests and collective security interests may sometimes prove to be irreconcilable. Still, the nature of many emerging security challenges makes the established compartmentalization of responsibilities between the public and private sectors appear increasingly anachronistic.

Improve collective decision-making. Another obvious challenge pertains to response speed and, consequently, the question of political control. Cyber attacks offer the most glaring example: They simply do not leave one with enough time to engage in lengthy deliberations, let alone with the opportunity to seek parliamentary approval of a response. While this challenge is already significant on the national level, it is even more severe in a multinational context. To overcome it, nations must agree on rules of engagement or pre-delegate authority to certain entities. This quasi-automaticity runs counter to the natural instinct of governments to retain political control over every aspect of their collective response; yet the slow, deliberative nature of consensus building is unsuitable for the challenge at hand. The consensus needs to be built before the event occurs. Consequently, NATO is constantly reviewing its decision-making procedures and seeks to adapt them to the unique circumstances imposed by nontraditional security challenges, such as cyber attacks or hybrid warfare.

Build a new culture of debate. Finally, allies must use NATO as a forum for sustained political dialogue about broader security developments. While NATO is engaged on several continents, its collective mindset is still largely Eurocentric and reactive. As a result, many NATO members approach discussions on potential future security issues hesitantly, worrying that NATO’s image as an operations-driven alliance will create the impression that any such debate is only a precursor to military engagement. While such misperceptions can never be ruled out entirely, the allies should nevertheless resist putting themselves hostage to the risk of a few false press reports about NATO’s allegedly sinister military intentions. Indeed, the true risk for NATO lies in the opposite direction: by refusing to look ahead and debate political and military options in meeting emerging challenges, the allies would condemn themselves to an entirely reactive approach, thus foregoing opportunities for a proactive policy. Such a culture of debate is all the more important because many new security challenges do not affect all the allies in quite the same way. A terrorist assault or a cyber attack against just one ally will not necessarily generate the collective sense of moral outrage and political solidarity seen after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Consequently, political solidarity and collective responses may be far more difficult to generate. Admitting this fact is not fatalism. It is simply a reminder that the new threats can be divisive rather than unifying if the allies do not make a determined effort to address them collectively. On a positive note, there are some indications that this cultural change in NATO has finally begun, because allies have become more willing to discuss potentially controversial issues in a brainstorming mode. This welcome development must now be sustained by beefing up NATO’s analytical capabilities, including improved intelligence sharing and longer-range forecasting. Over time, these developments should lead to a shift in NATO’s culture toward becoming a more forward-looking organization.

Achievements and challenges

Given the many structural differences between traditional and nontraditional security challenges, it should not come as a surprise that NATO’s forays into addressing the latter have been difficult. However, since the 2010 Strategic Concept set the stage, much has been achieved. This is particularly true for cyber defense, which has seen rapid progress, including the development of a distinct NATO policy, the definition of cyber as a distinct operational domain, and its mention in the context of the Article 5 collective self-defense clause. While some experts hold that nations remain secretive, even with allies, regarding their cyber vulnerabilities and capabilities, the need for NATO to meet the cyber challenge has been fully acknowledged. The attribution challenge remains difficult to meet in a collective framework, yet the NATO allies have demonstrated the political will to “name and shame” Russia for using the nerve agent Novichok to try to kill former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal.

Other subjects, such as energy security, have evolved less rapidly, but the combination of policy development, inserting nontraditional threats into NATO’s exercises and setting up tailored training courses has given NATO’s role in areas such as counterterrorism, energy security and WMD proliferation a sharper profile. For example, NATO’s role in the fight against terrorism — which includes operations in Afghanistan and participation in the counter-ISIS campaign, defending against improvised explosive devices, chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats, biometrics, and identifying returning foreign terrorist fighters — clearly benefited from the visibility of a dedicated foothold in NATO’s bureaucracy, as well as from the Alliance’s education and training opportunities.

Nontraditional challenges have also been a convenient venue for some partner countries to move closer to NATO. Moreover, several of NATO’s Centres of Excellence have proven to be invaluable analytical resources, as have the two Strategic Commands. NATO’s support for scientific research also focuses on nontraditional challenges, including climate change and water security, and NATO has built ties to the scientific community to discuss these and other issues. The allies have also increased their understanding of hybrid threats, notably in cooperation with the EU. In short, NATO has become a serious interlocutor on nontraditional challenges.

All this is not to say that NATO has entirely mastered the difficult terrain of nontraditional security challenges. There are still areas where the gap between expectations and reality remains wide. For example, while the 2010 Strategic Concept refers to climate change as a potential threat multiplier, the allies have yet to develop a visible collective approach to dealing with this phenomenon. The same holds true for resource scarcity and similar issues: While NATO should not militarize what are essentially economic matters, the lack of interest in such topics could lead to all kinds of unwelcome surprises. By the same token, despite a variety of forecasting efforts by the Alliance as well as by individual allies, NATO as a collective entity has not yet embraced this methodology.

Above all, however, on the question of whether NATO could eventually cede its accustomed leadership role, the jury is still out. For NATO to only play a supporting role alongside other stakeholders would require yet another sea change in the Alliance’s culture. As a former high-ranking NATO official put it, “NATO is not accustomed to sharing leadership and decision-making responsibilities with a range of different civilian actors outside the conventional military chain of command.” And yet this is precisely what the Alliance will have to learn.

Conclusion: a new social contract

Dealing with nontraditional challenges requires a paradigm shift away from deterrence and toward resilience — an enormous challenge for both individual states and alliances. A security policy that accepts that certain threats cannot be prevented through deterrence and that some damage will inevitably occur will be difficult to explain to populations that have become used to near-perfect security. Thus, such a policy will be charged as being fatalistic or scaremongering, while others will interpret it as an excuse for governments to spy on their citizens or simply as an excuse for increasing defense budgets.

Nontraditional challenges thus bring home a most inconvenient truth: What once was almost absolute security has become relative security. Everyone can become a victim, anytime, anyplace. This has far-reaching implications for the modern state, which in the final analysis derives its legitimacy from the fact that it can protect its citizens. Nothing less than a new social contract is needed. Governments will have to admit that in the age of cyber attacks, terrorism and climate change they can no longer protect their citizens as comprehensively as in the past — and yet, these very citizens will have to give the state permission to use force, including offensive cyber force, sometimes earlier and perhaps more comprehensively than traditional ideas of self-defense may suggest.

The implications of these changes are far-reaching indeed. Efforts to introduce such a new social contract will face stiff resistance. However, inaction would ultimately be more expensive. No one has expressed this better than one of the world’s richest men, Warren Buffett. The famed investor had long been thinking about the question of how major disasters would affect the insurance industry. But he had not turned his reflections into concrete action. In a letter to his shareholders, written a few weeks after the tragedy of 9/11, Buffett admitted that he had violated the Noah rule: Predicting rain doesn’t count; building arks does.

Comments are closed.