Countries use a range of strategies to keep energy supplies flowing

By Dr. Pál Dunay, former Marshall Center professor

Power generated from solar and wind — though still a small percentage of the energy supply when compared with fossil fuels — is on the rise as nations continue their shared undertaking to transition to renewable energy.

Two considerations underline this process:

- Developed countries’ intentions to reduce dependence on imported coal, oil and gas while transitioning to renewables such as solar and wind, which after major initial investment can be available to most nations and can provide a level of energy independence unachievable with fossil fuels.

- The campaign to slow down and then stop global warming through the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions.

As the world transitions from its reliance on fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, it may result in a wide redistribution of wealth and power. Countries whose wealth is based on the production of fossil fuels will lose economic power and global influence in the face of shrinking demand. Of course, such a process is somewhat predictable and potential losers may adapt to it. However, such a change also hurts domestic interests within these countries. Russia is a prime example: Where economic and political power are intertwined, there will be strong opposition to this transformation irrespective of whether it manifests itself in state capture by powerful interests (the 1990s) or state control of the economy (the 21st century). The longer the adaptation is postponed, the more loss accumulates. Russian experts have repeatedly called attention to this: Sberbank CEO German Gref said in 2016 that his country must “honestly admit that … the era of oil [is] over and … in the new technology-driven world the difference between the leaders and losers [will] be larger than during the industrial revolution.” The scholar Lilia Shevtsova noted more generally that Russia’s economy “is not diversified and is built on the commodity market.” However, this is now changing quickly, not because the Kremlin is heeding these concerns, but to move to a war economy to support its aggression against Ukraine.

If the move away from coal and oil continues — as well as increasing concerns about the burning of gas contributing to climate change and the safety of nuclear power generation — there may be an even more radical departure from the recent past. It’s an open question as to when methane from natural gas will be designated as a major component of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, and if widespread concerns about the safe storage of used nuclear fuel rods could reduce the acceptance of nuclear power. These two matters have been diplomatically taken off the European Union agenda or deferred to a later time.

Although those are familiar risks, it is not feasible to instantaneously abandon every existent energy source. However, once the transition is accomplished, the world will be all the more exposed to a new dependence on renewables that present their own challenges. Primarily, electromobility will result in reliance on so-called rare earth metals, over which some countries, first and foremost China, would like to gain near-monopolistic control. Furthermore, the production of lithium batteries raises two issues: the contamination and/or depletion of water resources; and the processing of used batteries — an issue loosely resembling concerns over uranium rods. The challenges are enormous and the process is indeterminate. It could contribute to a further rearrangement of the energy sector, resulting in additional changes to the world economy.

As affluent Western democracies lead the transition to reduce, stop and, it is hoped, reverse global warming, success depends upon determination, leadership and influence. Decarbonization can be only a global success or a universal failure. For this reason, it is essential that the West succeed in its own backyard, where it controls policy, and that it be diplomatically and economically persuasive globally in places it does not. Western societies are somewhat divided on how swift, how radical the transition should be and how much cost is acceptable in moving toward zero global warming. At one end of the spectrum, there are radical environmentalists who are prepared to endure massive sacrifices to achieve the zero-emission objective as rapidly as possible. At the other end are opposing interests that will not hesitate to slow the process if it contributes to their political support or threatens their financial or economic positions. Regardless, economic tradeoffs will be required. Transitions of this magnitude come with not insignificant costs. Mainstream political forces must find the balance between staying on course and making the transition affordable, while ensuring steady movement toward carbon neutrality. It’s clear that some large economies, such as India’s, will lag behind the EU and North America, but short of largely unforeseen developments, it and most other countries will follow.

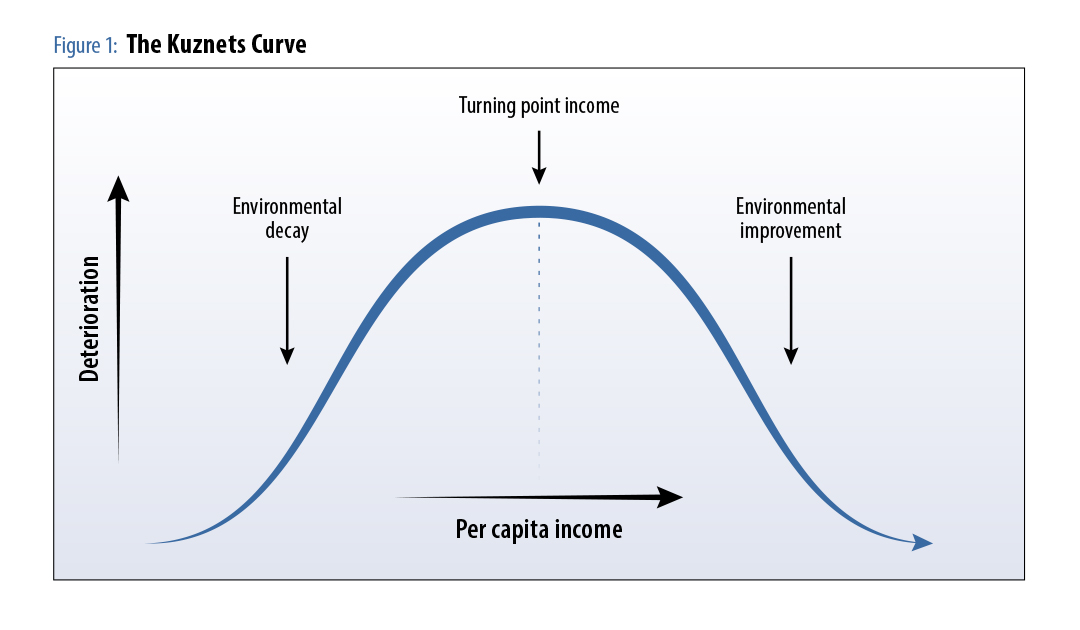

Globally, countries of the diverse developing world — and some in Europe — have pushed for financial and technological assistance, claiming they lack the resources necessary to abandon high-carbon technologies. In addition, many believe that rich, developed countries are obligated to provide assistance because, while now insisting that the rest of the world develop without exacerbating global warming, their development in past decades was fostered by industrial activities and technologies that heavily contributed to the current climate dilemma. This consideration is illustrated by the so-called Kuznets Curve (Figure 1). It shows the relationship between environmental degradation and per capita income, where pollution emissions initially increase with economic growth but then decline at high income levels, leading to environmental improvement.

The idea of energy security is a relatively new and developing concept found at the crossroads of state security and human security. States are more secure with a guaranteed and uninterrupted energy supply. Energy security is achieved when a country has energy reserves, a balance of supply and demand, and a balanced energy trade. Energy is more affordable and the system more diverse with an ample diversity of energy sources. Energy security is also a human security issue. Citizens in advanced and properly organized societies expect consistent energy availability at affordable and predictable prices. If, and when, this cannot be provided, they may express their dissatisfaction in ways that undermine social cohesion. It may seem that democracies are more vulnerable to social disruption from energy shortages and unexpected price hikes, but there is no supporting evidence of that. It is a misconception because democracies are typically quite resilient and can maintain popular support in spite of negative developments. Authoritarian regimes, on the other hand, can be shaken as a result of energy-related issues. For example, the “liberalization” of the price of liquefied petroleum gas in Kazakhstan in January 2022 was the immediate reason for an outbreak of demonstrations.

Every energy-dependent state develops defensive energy strategies to mitigate the risks and potential consequences of its dependency. Such countries provide for their security through risk-mitigation measures, such as diversification of energy sources and suppliers, and entering technical deals, such as building energy reservoirs, complementary gas or oil supply lines and interconnectors, or electricity exchanges. All of this may result in perceived wasteful spending, but those costs should be measured against the potential risks of interrupted supply.

In turn, major energy-supplying states develop offensive strategies. Suppliers endeavor to secure a profitable dependency on their product. Suppliers are typically flexible and willing to expand their normal capacity limits, although, understandably, at higher prices. Maintaining such reserve capacity that can be activated also has extra costs for the supplier. For decades, Saudi Arabia had a monopoly as the source of an expanded, complementary supply of crude oil. However, when Russia created a shortage in the world gas market in 2022 — to create havoc and blackmail its European customers — it soon became clear that other major suppliers of Europe, such as Norway and Qatar, did not have sufficient supply flexibility to compensate for the shortage of Russian gas. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the United States provided the necessary reinforcement of Europe’s energy supply, and now nearly half of total LNG imported by Europe comes from the U.S. We also learned that because of the rapid globalization of the world gas market, dependency on pipeline-based gas supplies is not nearly as severe as it was when, in the early 1980s, Germany was warned not to become dependent on Soviet gas piped from Siberia.

Because energy security is critical for every state, interrupting the energy supply as a form of blackmail might seem a good idea in the short run, but it is strategically unwise as it generates additional costs in lost trading partners and, more importantly, trust. Energy suppliers that are separate from and not controlled by a governmental political power would seem more trustworthy in their ability to provide a consistent and uninterrupted supply.

The focus of this edition of per Concordiam is on how Russia’s energy trading partners have adapted in light of Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine. The ongoing war of attrition emphasizes the need to quickly reduce dependency on Russian gas (as well as oil and coal). Even if the war ends soon — because of the structural changes to Europe’s energy supply lines and increasing reliance on renewables — a return to imports of Russian fossil fuels will be partial at best or minimal at worst. There continue to be lasting structural effects on the world economy and international politics that complement other elements of an energy decoupling between Russia and the EU, and an ongoing global energy realignment.

Comments are closed.