Economic Needs and Global Desires

By Dr. Cüneyt Gürer, Marshall Center professor

Photos by The Associated Press

When thinking about China’s engagement in Europe, it is important to consider how Turkey plays into the strategic picture. Turkey straddles the Europe-Asia divide and serves as a gateway into the European economic zone. In this regard, it is important to understand how China’s engagement with Turkey affects Europe. At the strategic level, Turkish and Chinese relations could be best described as a friendship of convenience, with each side having its own interests and priorities. Cooperation increased significantly after the signing in 2010 of a strategic partnership agreement that benefited Turkey in the short term, but that also provided China with long-term strategic advantages. China’s approach to Turkey is closely aligned with its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) program (later renamed the Belt and Road Initiative), and Turkey considers China’s growing interest in the region as helpful in meeting some of its economic challenges. But these short-term political calculations fail to address some significant issues, putting Turkey in a vulnerable position against China’s more assertive policies in the region.

China’s desire to reach Europe creates opportunities for Turkey to fund major construction projects begun before China unveiled OBOR. At the same time, Turkey’s current economic challenges require external cash transfers to resolve a currency crisis that is due in part to changes in its selection of strategic partners in the region. Turkey’s pursuit of a short-term economic remedy makes China’s entry into Turkey much easier and increases China’s ability to gain a foothold in the region.

Although some analysts warn that China’s involvement in Turkey’s critical infrastructure projects comes with potential traps, most experts in Turkey see the move as an opportunity. That opinion fails to address the risks involved in allowing China to take majority ownership of the infrastructure projects. Turkey’s population seems to have a more realistic understanding of China’s motives. According to the Transatlantic Trends 2021 survey, 53% of Turkey’s population has a negative view of China’s influence in global affairs, and 47% perceives China as a rival rather than a partner.

Chinese and Turkish diplomatic relations began in 1971 but did not progress until the 2010s because of structural, political and economic reasons. Turkey had always prioritized economic and political relations with the West and established partnerships to institutionalize these relationships. It actively promoted the international rules-based system. As Turkey moved toward a so-called independent foreign policy, it shifted away from Western institutions and created a need for a new direction at the global level. The complexity of domestic political and economic challenges that accompanied the introduction of a presidential political system in 2018 increased the need for new partnerships in the world that would contribute to the construction of a new regime in Turkey (defined as the “new Turkey” by the governing Justice and Development Party), and address economic challenges in the country.

Turkey’s policy departures from the Western bloc provided an opportunity for China to pursue its interests in the region. At the same time, China’s new policy of becoming more involved in world affairs and generating global influence through OBOR created an alternative for Turkey to fulfill its emerging economic needs. China’s role in the Turkish economy has increased significantly over the past decade as Chinese companies have invested in critical infrastructure such as bridges, roads, ports and telecommunications. As a result, China has gained strategic advantages in Turkey and the region because Ankara is trying to address its pressing economic challenges with Chinese loans and currency swaps.

Turkey’s geostrategic location makes the country an important partner for China’s OBOR strategy, and China became a convenient alternative when Turkey looked for ways to solve its political and economic problems after the attempted coup in 2016. These two dynamics made the relationship significantly meaningful for both sides. The two countries have now signed 11 bilateral agreements to extend their partnership on strategic issues such as trade, transportation, banking, energy and health. While China’s OBOR-linked interests help with Turkey’s economic needs, they also represent substantial long-term ramifications and risks.

Short History of Turkish-Chinese Relations

The first diplomatic contact between Turkey and China dates to 1934 when the two countries signed a friendship and commerce treaty. However, after the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established in 1949, relations between the countries were terminated. Because Turkey supported South Korea during the Korean War, along with the U.S. forces under the United Nations’ command, China and Turkey became adversaries. The countries had no contact until 1971, when Turkey supported the U.N. decision to restore the PRC’s membership in the U.N. and recognized China’s new regime. However, significant improvement in their relations did not occur until 1982, when Turkey’s president visited China. It was two years after a military coup in Turkey and the new Turkish government, run by the military junta, set out to establish alternative economic relations to ease the country’s post-coup isolation. The two countries extended their relations by establishing the Turkey-China Business Council in 1992, and then elevated them to a strategic partnership in 2010.

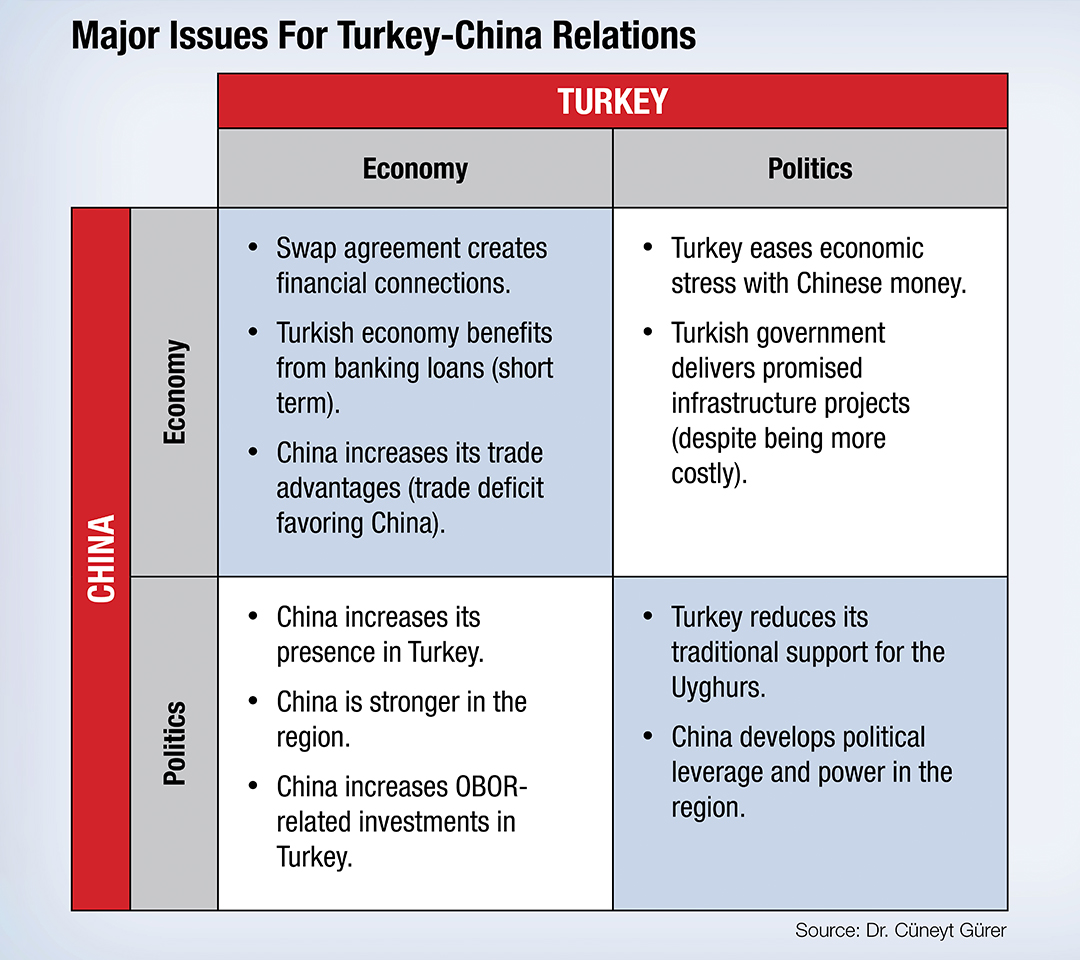

Turkey’s new regional and foreign policies after 2011 required new alliances and alternative relations with the emerging powers. China presented an opportunity to advance Turkey’s political and economic goals. Those two issues — economy and politics — are the major components of the relationship. Although issues such as the cultural and ethnic ties of Uyghurs to Turkish society and Chinese cultural initiatives in Turkey require some attention, these and all other issues are connected to the economic and political components.

Turkey’s Economy and China

The World Bank’s 2021 assessment of the Turkish economy indicates that in past years, Turkey’s macroeconomic structure has become more vulnerable and uncertain due to rising inflation, unemployment, and its currency and debt crises. The combination of a trade deficit and a drop in revenues from tourism widened Turkey’s deficit in April 2020 to $5.6 billion, up from just $500 million in late 2019. In 2018, the value of the Turkish lira dropped 40%, and the Chinese state-owned Industrial and Commercial Bank provided $3.6 billion in loans for ongoing energy and transportation projects, a move the media defined as a lifesaver for the projects. According to a Harvard Business Review analysis in 2020, China uses direct loans as a way of increasing influence in receiving countries, which creates the potential for a debt trap for the receiving countries and a hidden debt problem globally. According to a National Bureau of Economic Research analysis, almost all of China’s lending and investment abroad comes from state-controlled entities, and at least 50% of China’s lending to developing countries is not reported to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank, creating a hidden debt problem in the global financial system.

For the most part, information on Chinese direct loans is not public. Nevertheless, available information indicates an increase in loan transfers from China to Turkey in recent years. In 2019, Turkish Vakifbank accepted a $140 million, one-year loan from China Eximbank to finance trade between Turkey and China, marking the first transaction between the two banks. In the same year, the Industrial and Development Bank of Turkey reported receiving a $200 million loan from the China Development Bank under OBOR agreements, a first for those two banks. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China purchased the majority of shares in Turkey’s Tekstilbank in May 2015 and became the first Chinese bank to operate in the Turkish market with commercial, investment and asset management banking licenses. Chinese investment rescued Turkey’s economy as the country ran out of crucial foreign reserves needed to pay down its debt and lower the pressure of economic crises in the country. By introducing more Chinese involvement in its banking sector and allowing Turkish banks to receive loans from Chinese state-owned banks, Turkey risks Chinese involvement in the most critical sectors of the country and allowing China to become more powerful in the region.

China uses currency swaps between central banks as an OBOR instrument globally. Turkey signed a currency swap deal with China in 2012, allowing the central banks of both countries to exchange their national currencies to reduce economic pressures. In June 2019, the Chinese central bank transferred $1 billion to Turkey, helping President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan prevent an economic crisis just before an election. In June 2021, Erdoğan stated that Turkey and China had agreed to increase the swap agreement capacity from $2.4 billion to $6 billion. The IMF considers bilateral swap lines a valuable part of the global financial safety net (GFSN) and an appropriate response to economic crises. However, Turkey’s swap agreements with China go beyond a financial safety instrument. According to international political economist and China analyst Daniel McDowell, China uses swap agreements as more than a financial safety instrument, turning them into a tool of Chinese financial statecraft by using “national financial and monetary capabilities to achieve foreign policy ends.” From a strategic point of view, China considers swap agreements as connection points and cooperation priorities for OBOR. For China, the swap agreement with Turkey is more than a GFSN tool; it’s a significant component of OBOR aimed at financial integration (coordination and cooperation in monetary policy) among OBOR countries.

Trade relations between China and Turkey reached $23.6 billion in 2020, making China the third-largest trade partner with Turkey, after Russia and Germany, according to then-Turkish Commerce Minister Ruhsar Pekçan. The number of Chinese investments in Turkey increased 120%. There are 8,000 Chinese workers and more than 1,000 Chinese companies operating in Turkey. Chinese investments in Turkey amounted to $2.8 billion in 2020 and were valued at $1.5 billion between 2005 and 2018. In 2021, China sought to increase its investment in Turkey by $6 billion per year. In late 2021, in response to Turkey’s increasing inflation and currency crisis, Erdoğan announced that Turkey would transition to a Chinese-style economic system, but did not provide details.

OBOR and China’s Investments

OBOR includes six economic corridors of power connecting China with Pakistan, Mongolia, Russia, India, Myanmar and Central/West Asia. Turkey is located in a strategic position on the China-Central Asia and West Asia Corridor. This economic corridor increases connectivity among China, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Turkey and Uzbekistan. China became more involved in the region after announcing its OBOR strategy, and Turkey played a central role in the Central Asia and West Asia Corridor. Before the initiation of OBOR, Turkey started a regional transportation project called the Middle Corridor Initiative (MCI). Turkey and China later agreed to merge MCI and OBOR because the two projects overlapped. In November 2015, during the G-20 Leaders’ Summit in Turkey, the countries signed a memorandum of understanding aligning OBOR and the MCI.

The MCI objectives are to increase trade relations between Central Asian countries and to support the economic growth of countries in the Caucasus region. Originally a Western-oriented project supported by the U.S. and the EU, the MCI project is now under the heavy influence of Chinese investment. However, according to an analysis by the Slovakian-based think tank GLOBSEC, uncertainties in the Turkish domestic political structure and a lack of long-term strategies in the region make Turkey an unreliable partner for China. Therefore, “despite a very welcoming discourse from Ankara and Beijing on Silk Road cooperation,” the analysis found, “it is difficult to say whether there is a road map to integrate” OBOR and the MCI. Despite some reluctance by China, earlier MCI planning and initial investments made it easier to integrate OBOR into MCI, and China made significant investments in some of the MCI projects connected to Turkey. It completed the Marmaray undersea railway, the Eurasia Tunnel, and the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge connecting Europe and Asia through Istanbul (directly connecting the Asian side to the new Istanbul Airport). The MCI is behind several other infrastructure projects, such as the Çanakkale Bridge, the Edirne-Kars high-speed rail and the Three-Level Tube Tunnel.

China made significant investments in these projects and continues to increase its investments in projects in the planning phase. In January 2020, a Chinese consortium bought 51% of the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, which is considered a part of the MCI and has significant strategic value. China invested in the Marmaray undersea railway in Istanbul, a transportation project that is part of the MCI connecting the Asian and European parts of the city. In November 2019, as a symbolic action to demonstrate that these investments connect China to Europe, a train departed from Xi’an, China, and arrived in the European part of Turkey using the Marmaray. This had symbolic significance, showing for the first time that a train could travel nonstop from China to Europe. In addition, in 2015 a Chinese consortium bought 65% of the Kumport Terminal, Turkey’s largest container terminal on the northwest coast of the Marmara Sea, which has a significant strategic link to Europe.

The controversial Istanbul Canal project is the largest that Erdoğan has initiated and, according to experts, it will have significant environmental, geostrategic and political consequences. However, past experience shows that announcing such projects brings significant support to Erdoğan during elections. With its magnitude, the project needs a significant amount of foreign investment, which presents an opportunity for China. Erdoğan publicly stated that he expected China to contribute to the $15 billion project and to take part in building six bridges on the new canal. According to Turkey’s transportation minister, Chinese, Russian, Dutch and Belgian companies are interested in investing in and financing the project. The minister also mentioned the connection between the Istanbul Canal project and OBOR and added that the project will boost Turkey’s share of global trade. Various news agencies also reported that Chinese companies are interested in investing in the project. But the project is a potential debt trap, and if Turkey cannot meet the financing obligations, a strategic route connecting the Black and Aegean seas could be left under Chinese control.

China has also made investments in Turkey’s energy projects. Chinese banks are funding the $1.7 billion Emba Hunutlu coal-fired power plant being built in Adana on the Mediterranean Sea. The plant, which is projected to produce 3% of the country’s electricity, represents the largest Chinese investment in Turkey. Ankara also plans to sign a deal with China’s State Nuclear Power Technology Corp. to build Turkey’s third nuclear power plant.

Turkey’s Approach to the Uyghurs

Human rights violations against Uyghurs in Xinjiang pose a dilemma for Turkey in its relations with China. In 2009, before the countries entered into strategic partnerships, Erdoğan, who was Turkey’s prime minister at the time, called China’s actions in Xinjiang “genocide” and requested an international response. And Turkey has long offered sanctuary to Uyghurs who had escaped from China. But Turkey’s approach to China changed dramatically as its economic dependency grew over the past decade. Abdulkadir Yapçan, a Uyghur political activist who had lived in Turkey since 2001, was arrested in 2016 and detained until his release in 2019 after a lengthy judicial and administrative process. During this time, Turkey began working on an extradition treaty with China that Erdoğan has signed and that was pending the approval of the Turkish parliament as this article was being written. As a result, Uyghurs in Turkey have been living in fear of being deported to China. Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, Turkey’s minister of foreign affairs, said in 2017 that “Turkey considers China’s security as its own security and will not allow any activities in Turkey targeting and opposing China. Additionally, we will take measures to eliminate any media reports targeting China.” In 2021, Turkey cracked down on Uyghurs protesting against China. The shift, based on political calculations, has not been widely supported by the Turkish public.

According to Metropoll, a private polling organization in Turkey, 53.2% of the public in 2021 considered the government’s response to China on the treatment of Uyghurs to be inadequate. To counter the criticism, Turkish officials issued remarks decrying China’s arbitrary arrests, physical assaults and political brainwashing in internment camps and prisons. Deng Li, China’s ambassador to Turkey, issued a statement warning Turkey that such utterances would cause concern among Chinese investors and “would inevitably undermine bilateral ties.” Erdoğan remained silent on the issue. But for many, what was more interesting was to see the silence of Erdoğan’s coalition partner, the Nationalist Movement Party, which uses nationalist discourse at the domestic level at the highest possible volume whenever it fits its political agenda. COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy also had an impact on Turkey’s response to the Uyghur issue; the country was among the first to purchase the Chinese Sinovac vaccine, which at the time had not been approved in other countries. According to an analysis by the nonprofit Global Voices organization, Turkey’s participation to the Sinovac vaccine significantly contributed to China’s global vaccine diplomacy and its international prestige at the early stages. However, China delayed the delivery of vaccines to Turkey to put pressure on the parliament to ratify the extradition treaty. According to Andy-Ar, a Turkey-based social research center, poll results in December 2020 showed only 5% of the Turkish people trusted the Chinese vaccine.

The Way Forward

On January 4, 2022, Reuters reported that a group of Uyghurs living in Turkey had filed a criminal complaint with the chief prosecutor’s office in Istanbul against Chinese officials, accusing them of committing genocide, torture, rape and crimes against humanity. As this article was being written, neither Chinese nor Turkish officials had made any statements about the complaint. But it shows that the Uyghur issue will remain an obstacle to Turkey-China relations, though China considers Turkey a significant piece of its OBOR strategy.

China is watching Turkey’s foreign policy choices closely. According to Jale Özgentürk, economic news editor of Turkey’s Cumhuriyet newspaper, China’s interest in investing in Turkey entered a wait-and-see stage in 2021. One of the reasons for that loss of interest is the rapprochement between Erdoğan and U.S. President Joe Biden in June 2021. According to the GLOBSEC think tank, Beijing is hesitant to reveal its grand strategy to Ankara because of Turkey’s memberships in NATO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, as well as failed deals to build a nuclear power plant and an air defense system. The Uyghur issue adds another complication because Turkey’s population supports the Uyghur cause, and the ruling elite prefers to stay silent because of economic concerns. China is also aware that the Turkish public prefers Western institutions and culture over China’s institutions and culture. That lack of social support means China will invest more in social projects and public relations to boost its image in the country. China has opened four Confucius Institutes in Turkey, all of them at prestigious universities and all working to increase exchanges between the two countries.

Despite some headwinds, there is sufficient evidence to show that China’s interest in Turkey is growing, and that Beijing has been steadily increasing its presence in the region. Turkey’s departure from Western-oriented policies and economic partnerships, and its failure to recognize China’s long-term intentions, contribute to China’s expansion into the country. The lack of transparency in Turkish-Chinese relations is another important factor that makes Chinese expansion in Turkey easier. Experts in Turkey must rely on limited data to make their analyses and, most important, much of that analysis takes Chinese economic involvement at face value rather than focusing on the underlying risks originating from China’s political regime and concealed investment strategy. From a short-term economic analysis, it might be correct to assume Chinese investments in Turkey would bring relief to the country’s shaky economy. However, failing to address the long-term strategic impact of the financial deals, and the structural challenges that created the economic hardship in the first place, will leave Turkey worse off economically than it is today.

In 2023, the Republic of Turkey will celebrate the 100th anniversary of its founding. China has now become an important economic actor in Turkey and is working on cultural and social image-making to increase its approval within Turkish society. The lack of transparency in the details behind the countries’ cooperation makes it difficult to fully gauge the level of threat posed by the Chinese presence in the country. But publicly available information provides enough evidence to show that China’s presence in the region is stronger than ever. At the same time, China uses the wait-and-see strategy to assess Turkey’s commitment to its relations with Western actors and balances its actions accordingly. Turkey’s domestic political actions are based on short-term gains and a “stay-in-power” strategy. Turkey has the potential to change the power balance in the region. It is not too late to return the balance back to its origins, which would benefit Turkey in the long run.

Comments are closed.