European Countermeasures Against Chinese Influence Operations

By Dr. habil May-Britt U. Stumbaum, team leader for Project Asia Pacific Security at the Bundeswehr Universität Munich, and Susanne Kamerling, associate fellow at the research group War, Peace and Justice at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University, The Hague, Netherlands

China has used COVID-19 to shape its image as “a responsible and benign world leader” and a leading power in reforming the international political system. In tune with Russia, China trumpeted the narrative that Western countries and political systems are incompetent and unable to effectively manage crises. It seeks to popularize authoritarian models and win the hearts and minds of key stakeholders in targeted countries. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s stated aim to strengthen the county’s international “discourse power” has led to the adoption of new methods of information operations that include interference campaigns and disinformation

activities — on an industrial scale.

Beijing learns from methods long employed by Moscow, what Paul Charon and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer call in their 2021 report for France’s Institut de Recherche Stratégique de lʼEcole Militaire, the “Russification” of Chinese influence operations. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) uses hybrid operations to directly influence foreign countries’ policies and indirectly shape civil society’s attitudes toward China. The key objective of these operations is to ensure that narratives, third-party decisions and policies regarding China are in line with CCP interests. The strategic intent of these operations and the distorted flow of information resulting from propaganda, targeted disinformation campaigns, censorship and self-censorship pose a real challenge to Europe’s open societies, democracies, and established norms and values — striking at the very essence of European life and decision-making. The CCP’s intensified global outreach has forced the European Union and its member states to rethink their approach toward China and Chinese influence in Europe. A whole range of sector-specific measures have been taken by European countries to counter Chinese influence and hybrid operations, encompassing media and information, politics, business and investments, research, and academia — all in preventive, reactive and punitive ways.

Disinformation on an industrial scale

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified opportunities for Moscow and Beijing to push their geopolitical goals and national interests through influence, interference and hybrid operations. Many of these activities push — and cross — legal boundaries. Social media provides a cheap and easily scalable playing field for disinformation campaigns. A 2020 media manipulation survey by the Oxford Internet Institute in England found evidence of social media manipulation in each of the 81 countries surveyed, with more than 93% of those countries experiencing misinformation that is purposely being spread as part of a political messaging strategy. Influence and disinformation activities in digital environments have greatly intensified during the pandemic. Governments, though increasingly aware of the challenge, struggle to respond adequately, due in part to a lack of understanding of CCP tactics.

Integrating party and state resources, the so-called United Front Work (UFW) groups strive to control, indoctrinate and mobilize non-CCP masses to achieve CCP-defined objectives. As the congressionally mandated U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission pointed out, China seeks “influence through connections that are difficult to publicly prove and to gain influence that is interwoven with sensitive issues such as ethnic, political, and national identity.” The UFW benefits from the very factors that make for a thriving free society — a free press, a pluralistic political system and a broad array of civil-society institutions. The UFW follows common CCP tactics that can be tailored to specific circumstances. Under Xi, these UFW operations fall within four vectors, as outlined by China scholar Anne-Marie Brady in her 2019 submission to the New Zealand Parliament: 1) leveraging economic interdependencies and/or business interests; 2) seeking out and co-opting influential people; 3) seeking discourse control and self-censorship; and 4) where possible, leveraging the ethnic Chinese diaspora.

Key priorities for CCP operations in Europe in recent years have been silencing targeted countries regarding Taiwan in an effort to weaken Taipei politically, forcing countries to accept Huawei into their 5G networks, silencing targeted countries on China’s human rights abuses (including in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and against Falun Gong), deflecting responsibility for the pandemic, and positioning China as the medical savior of Europe and beyond. The diplomatic row between China and Lithuania, which now extends to all European Union member states that trade with Lithuania, is illustrative of the first vector outlined by Brady.

Interestingly, in Europe the targeting of political and business elites and party-to-party diplomacy is accorded more relative weight as an influence tactic than the targeting of diasporas — given that only a few European countries have sizable Chinese populations (unlike Australia, where 5.6% of the population indicated Chinese ancestry in its 2016 census). The strategy in Europe is to leverage economic factors to facilitate political influence. The CCP often hides behind proxies, using economic-political entrepreneurs — often former high-ranking politicians and diplomats connected to the CCP through their own business interests — to improve China’s image and align the targeted country with China’s specific political and diplomatic interests.

While Chinese and Russian influence objectives often converge in Central Europe and the Western Balkans — a shared desire to push the United States from the region, to infiltrate national and local institutions, and to capture elites — the CCP does not use a one-size-fits-all approach in Central Europe. Approaches range from inducement in Hungary (where the political climate supports Chinese influence campaigns), to a mixture of inducement and coercion in the Czech Republic (using primarily proxies and staying in the shadows), to low-profile inducement/coercion activities in Slovakia.

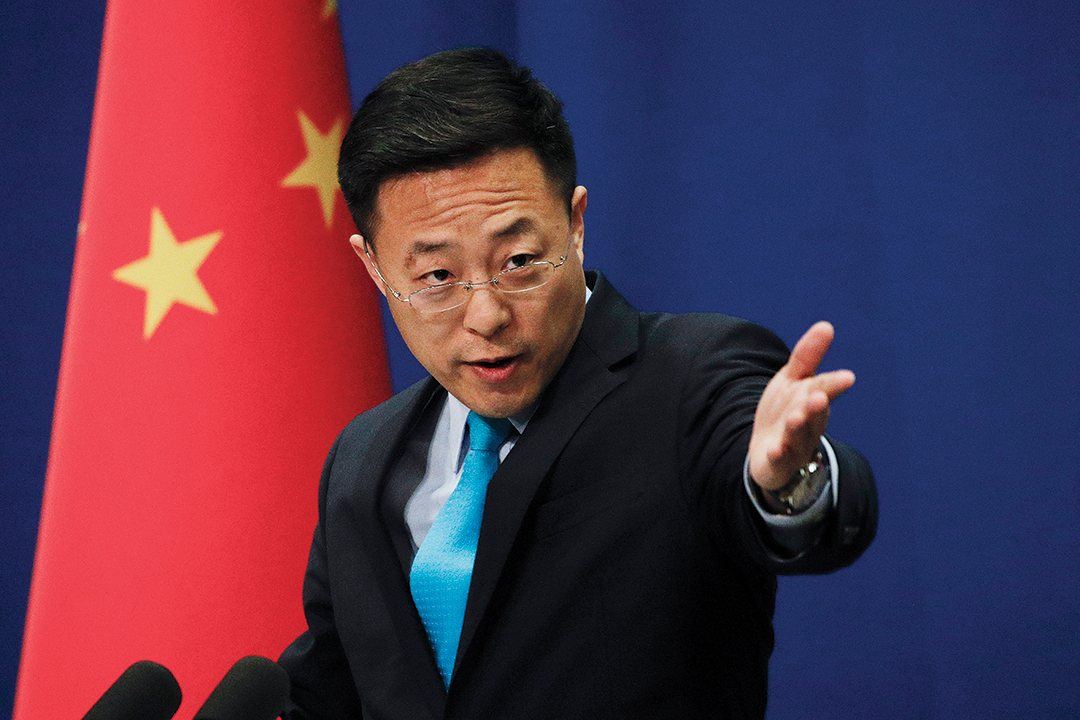

CCP activities in Europe — as in other open societies — exploit weaknesses in political, economic and social systems while exacerbating anti-Americanism and euroskepticism in targeted EU states. COVID-19 has acted as a catalyst for amplifying Chinese intimidation tactics in Europe. The notorious “wolf warrior diplomacy” tactic — an aggressive style of coercive diplomacy on social media adopted by China — was deployed by the Chinese ambassador to France, who attacked French lawmakers and researchers via Twitter over the EU’s sanctioning of Chinese officials for human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang. The Chinese Embassy in Sweden used the tactic to bully the Swedish government into restricting the Swedish press. Open democratic systems such as those in the EU are particularly vulnerable. Socially and politically polarizing issues are targeted, along with social divisions and policies considered harmful to the CCP’s interests. Striking examples can be found in China’s efforts to portray European states as incapable of helping their citizens during the first wave of COVID-19. At the same time, China attempts to portray itself (and hence the CCP) as the world’s savior while working hard to obliterate reports about the origins of the virus. Beijing employs a wide array of tools — including conditional investments/loan-indebtedness (particularly through its Belt and Road projects), lobbying and elite capture, acquisitions in media, tech businesses and vital infrastructure, and influence through academia, public diplomacy (e.g., panda diplomacy), culture and the Chinese diaspora. Beijing increasingly targets subnational and local governments that can pressure national governments “from below” and gain support for or prevent resistance to Chinese policies. The CCP thereby manages to incrementally and steadily — under the radar of conflict or heightened interest — change the very fundamentals of European public and private institutions and decision-making by altering norms, rules, information, attitudes and public opinion.

European responses — preventive, reactive, less punitive

The CCP’s pandemic campaign spurred European governments to address the challenges posed by Chinese influence, interference and hybrid operations.

Interestingly, Europe’s smaller states and younger democracies have responded better than its larger, older democracies. Russian interference in the Baltic states and some Central European states, such as the Czech Republic, has generally made them more vigilant about China. These countries have publicized disinformation campaigns and other activities tied to the CCP or other Chinese state actors. Political and intellectual opposition to totalitarianism in these countries has nourished resilience against CCP influence (e.g., the reporting of these activities in the Czech Republic by civil-society organizations such as Sinopsis, ChinfluenCE and CHOICE).

As recently as 2019, the EU called China a systemic rival that attempts to promote a governance model antithetic to the EU’s liberal values. With growing awareness of Chinese influence operations (along with other authoritarian states, first and foremost, Russia) the EU has implemented a set of instruments that include the Code of Practice on Disinformation (a set of standards to fight disinformation), a cyber-diplomacy toolbox and a cyber-sanctions regime (a set of tools and processes), and the Rapid Alert System, adopted as part of the EU’s Action Plan Against Disinformation. The Hybrid Fusion Cell was also created to receive, analyze and share information about hybrid threats. And cooperation with NATO has accelerated with the creation of the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats. Additionally, the European Commission established a centralized mechanism for screening foreign direct investments, an anti-coercion tool to counter economic coercion by third countries and a toolkit to mitigate foreign interference, especially in research and innovation.

EU members have responded to China’s tactics in three ways: preventive, reactive and punitive. The latter more often applies to countries geographically closer to China that are the target of prolonged and intense CCP operations. Most European countries focus on preventive and reactive measures. For example, Sweden established a whole-of-society and whole-of-government approach to build resilience against foreign interference from Russia and China. The government in 2019 named Fredrik Löjdquist as the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s first ambassador for countering hybrid threats and banned Huawei and ZTE from its 5G network.

Beyond these general responses, the EU and its members also reacted with a set of best practices for each vulnerable sector: In the media and information sector, for example, Slovakia enacted preventive legislation prohibiting cross-media ownership. France and Germany’s foreign investment screening process includes the media (print, radio and TV) as a strategic industry. Sweden invested in automatic fact-checking platforms with functionalities for self-checking by citizens, and in teaching children about fake news and propaganda. As a reactive measure, Germany’s Network Enforcement Act requires internet platforms to provide a process for users to report illegal content, such as hate and defamatory speech posted on their platforms. On the punitive spectrum, Latvia and Lithuania — the latter facing enormous pressure from Beijing for leaving China’s controversial 17+1 Central and Eastern European investment platform in 2021 — imposed fines and suspensions for media that spread disinformation and adopted tougher regulations on media originating outside the EU.

Best practices in politics and for elites include preventive acts, such as the Dutch government’s 2019 legislation restricting foreign political donations and the mayor of Prague canceling a sister city agreement with Beijing. Collective pushback included Germany’s parliament canceling a delegation trip to China after one of its members was denied a visa, and the Swedish media calling out attempts at press intimidation. A recent “naming and shaming” warning from MI5, the United Kingdom’s domestic counterintelligence and security service, to members of the British parliament, accused the well-connected, pro-CCP lobbyist Christine Lee, a Chinese-born lawyer, of working on behalf of Beijing to corrupt British politicians.

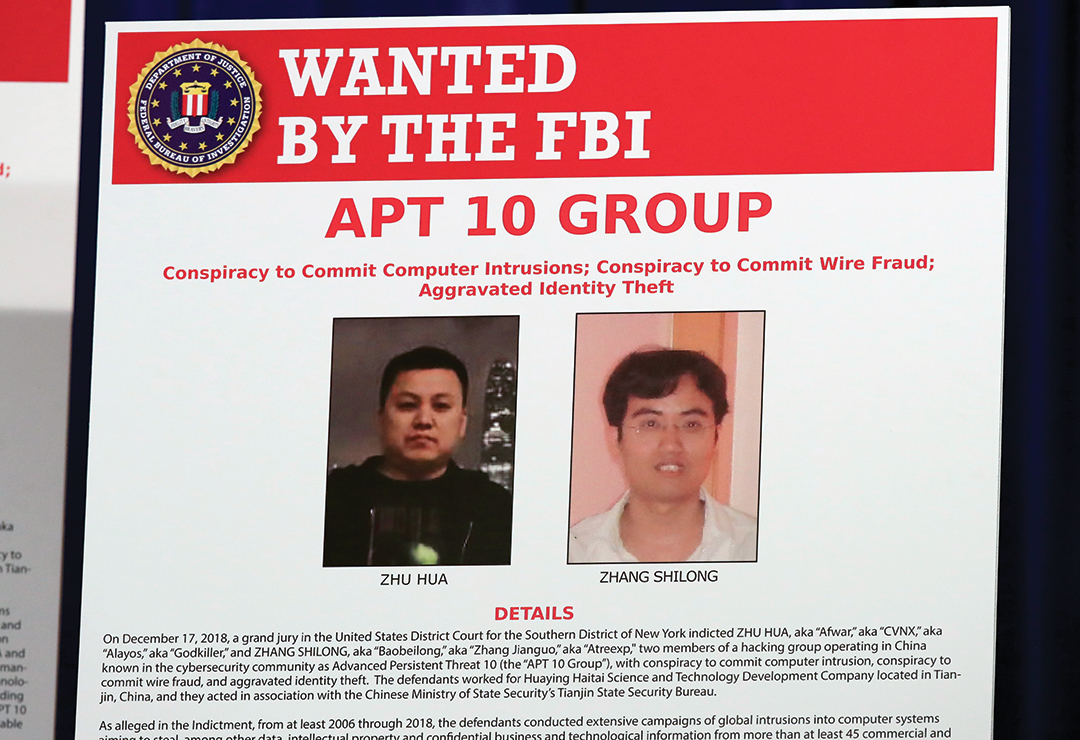

Best practices in business and investment largely revolve around preventive measures. The EU adopted the 2016 trade secrets directive to harmonize protection across the EU, and in 2019 adopted regulations for screening foreign direct investment. Several European governments involve their domestic security services in collecting information about the Chinese government’s corporate economic espionage to provide warnings to companies and other targeted actors. On the reactive front, British and Dutch intelligence and security services reported on Advanced Persistent Threat 10, a China-based hacking group that targets governments and telecoms.

Best practices in academia and research have generally been limited to preventive measures, such as awareness and resilience building. Some parliamentary hearings (especially in Great Britain) have occurred, ministry guidelines have been issued, and some universities have taken action. The 2020 report, “Towards Sustainable Europe-China Collaboration in Higher Education in Research” by the Leiden Asia Centre, a Dutch research center within Leiden University, outlined that Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the U.K. have issued guidelines for academic and research cooperation with China. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs has added a checklist for universities and other research institutes calling for greater awareness and caution in cooperation with China. The Academic Freedom and Internationalization Working Group, based in Great Britain, issued a code of conduct to protect academic freedom and the research community. All Swedish higher education institutions have discontinued their ties with Hanban, the Chinese public institution affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education and widely known to be the Confucius Institutes’ headquarters. Czech security services are briefing universities on potential risks. There have been some reactive measures in academia, including the closing of Confucius Institutes in Sweden and the Netherlands as the result of decisions taken by individual universities. In the Czech Republic, the Chinese Centre at Prague’s Charles University closed its doors after a scandal about secret payments received from the Chinese Embassy. Several universities have also taken actions against Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA) branches on their campuses, such as Cambridge University’s 2011 disbanding of its CSSA after the Chinese Embassy allegedly interfered in the election of the group’s president.

The way ahead: a whole-of-government/society approach

The EU and its members must continue to expand and implement the necessary measures to protect its democratic systems, open societies, norms and values. A whole-of-society and whole-of government approach is crucial to this endeavor. The EU and its members should find ways to use democracy’s strengths to protect them; transparency is key, but so is the strengthening of democratic narratives and practices inside the EU. Media outlets, publishers and digital platforms should be encouraged to refuse any cooperation with Chinese propaganda media outlets, to report economic or political pressure by China and to promote civil society campaigns against propaganda. The EU and its members should also support and fund independent research and journalism on China, educate relevant stakeholders about China’s influence techniques and raise awareness among the broader public, including through media literacy campaigns. The EU could also create incident trackers in various fields and coordinate investigations into CCP influence networks, all while systematically assessing the resulting risks. The EU and its members should respond firmly to economic espionage, increase naming and shaming of trade-secret thefts and stimulate criminal prosecutions of technology theft. They should strengthen the punitive response, where legal action should be considered to defend European citizens, including the Chinese diaspora, against CCP influencing and interference. Finally, to adjust the EU’s overall China strategy most effectively, the EU needs to broaden and promote the exchange of best practices and lessons learned with non-EU partners and in specific, like-minded states in the Asia-Pacific.

Comments are closed.