Restricting migrants in northern Europe will stress the economies of southeastern Europe

Dr. Valbona Zeneli, Marshall Center, and Joseph W. Vann

The current refugee and illegal migrant crisis in Europe has taken several years to boil to the surface. As European Union governments struggle to accept and relocate refugees, their attention seems to be shortsightedly focused on the immediate issue of how this crisis is affecting EU countries. Unfortunately, the situation is much larger than just the EU. As member states and other European countries clamp down on accepting asylum seekers and refugees, they trap refugees and illegal migrants in entry and transit countries. Based on current migration patterns, this will be most severely felt in the Western Balkans and could have serious unintended consequences for Europe in the form of a second wave of refugees. What is needed is a holistic and proactive approach to understanding and resolving this challenge.

If European leaders and policymakers fail to appreciate and take preventive measures to deal with this crisis, it has the potential to destabilize the entire Western Balkan region. The results could prompt a second and larger wave of asylum seekers, including a large number of Western Balkan nationals.

As European policymakers work to address this crisis, it is vital that they broaden their focus to include other serious migrant-related pressures gripping Southeast Europe and especially the Western Balkan countries of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia. For new policies to be effective, European leaders need to account for the economics of the much bigger refugee and economic migrant picture and, more importantly, its causes.

The current refugee and migration crisis is perhaps the largest since World War II. It has quickly become one of the most contentious European security issues. Left unaddressed, it has the potential to threaten the social fabric of the European region. This problem has grown so quickly that is has outstripped the ability of governments to comprehend it and react with carefully planned solutions. Instead of appreciating what this crisis means for Europe, leadership has responded slowly, disjointedly and reactively. There is little evidence of either an appreciation of how to deal with the problem in a coordinated fashion or of the impact of the crisis in the short and long terms.

Migration has forced Europe to face an unprecedented humanitarian, social and political crisis, as acknowledged by German Chancellor Angela Merkel when she remarked that this situation was “Europe’s biggest challenge: a collective problem that needs collective solutions.” According to the International Organization for Migration, over 1.2 million irregular migrants and refugees arrived in Europe in 2015, the majority from Syria, Africa and South Asia.

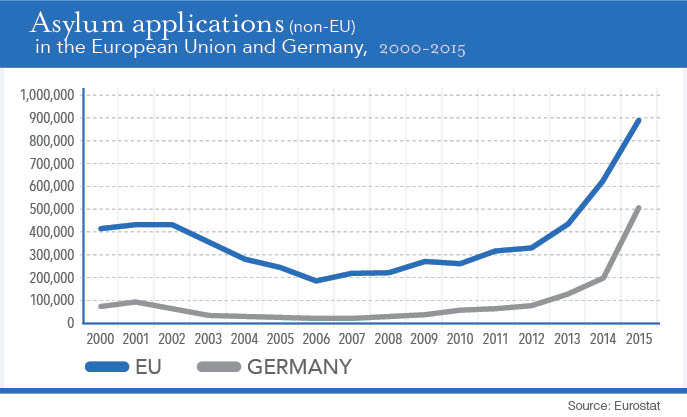

Judging from statistics in the first weeks of 2016, odds are that the number of irregular migrants crossing Europe will be higher in 2016. In the first three weeks of January, 37,000 new migrants and refugees arrived in Europe, 10 times the number in the same month in 2015. The burden of accepting refugees has fallen disproportionally on a few Western European states. Germany and Sweden have accepted the majority of refugees, while other EU member states have been less welcoming. According to Eurostat data, there were almost 900,000 registered asylum seekers in the EU. Germany received the most, totaling almost 500,000 at the end of 2015.

Judging from statistics in the first weeks of 2016, odds are that the number of irregular migrants crossing Europe will be higher in 2016. In the first three weeks of January, 37,000 new migrants and refugees arrived in Europe, 10 times the number in the same month in 2015. The burden of accepting refugees has fallen disproportionally on a few Western European states. Germany and Sweden have accepted the majority of refugees, while other EU member states have been less welcoming. According to Eurostat data, there were almost 900,000 registered asylum seekers in the EU. Germany received the most, totaling almost 500,000 at the end of 2015.

Absorbing a large number of refugees and migrants into any country is not easy. This has become a clear and painful lesson for all of the major destination countries. Wrestling with the moral and ideological response was easy compared to the reality of making it work. As we witness destination countries struggle, it is important to remember that these countries have more resilient economies and institutions than many others — especially those in the Western Balkans. These EU destination countries enjoy well-developed infrastructure and a long history of adhering to the rule of law, as well as good governance and strong institutions. However, EU nations have been surprised at how little they were prepared to manage and absorb the influx of refugees, asylum seekers and illegal economic migrants.

Understanding the economic and political strain that the crisis has placed on established EU countries becomes an important lesson for all. As the political climate of EU countries changes and citizens push back against accepting more refugees, EU leaders will seek ways to close their doors or limit the flow. The consequences of these actions will likely cause a chain reaction by trapping large numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and illegal migrants within non-EU countries that serve as entry and transit points for all involved in this migration crisis. This cause and effect relationship must be seriously considered by policymakers. If ignored, it creates the potential for millions of refugees to destabilize already stressed economies in the Western Balkans and makes for an easily predictable new refugee crisis.

Although EU population demographics indicate a need for foreign workers to bolster an aging workforce, its collective unemployment rate was just under 10 percent in early 2016. It is far from ready to expand the unemployed sector by adding refugees to the pool of job seekers. Although elevated, the EU unemployment rate is much better than the Western Balkan rate, which ranges from 17 to 35 percent. This makes the Western Balkans the last place to host refugees.

Further complicating today’s migration challenge, many refugees and asylum seekers are non-Europeans and have different religious and cultural identities than previous waves of migrants. This will likely make resettlement more challenging at the local level and may dissuade localities from accepting more refugees. Accepting fewer refugees in individual localities will impact refugee placement in the aggregate. As EU countries restrict inflows, some may see this as a “fix” to the crisis. However, this would be an illusion and a huge mistake. Unless there is a practical solution that stymies the outflow problem, the number of refugees will continue to grow and become trapped in entry and transit countries.

Further complicating today’s migration challenge, many refugees and asylum seekers are non-Europeans and have different religious and cultural identities than previous waves of migrants. This will likely make resettlement more challenging at the local level and may dissuade localities from accepting more refugees. Accepting fewer refugees in individual localities will impact refugee placement in the aggregate. As EU countries restrict inflows, some may see this as a “fix” to the crisis. However, this would be an illusion and a huge mistake. Unless there is a practical solution that stymies the outflow problem, the number of refugees will continue to grow and become trapped in entry and transit countries.

Unfortunately for the Western Balkans, the migrant crisis is mostly about geography. The “Balkan Route” is well-known and has long existed as the land route to the Middle East and Southwest and Central Asia. It is also known as a major smuggling route for moving illegal cargo into and out of Europe. This creates an added dimension to the problem, because human smuggling and trafficking networks have been quick to capitalize on the plight of refugees and migrants for profit.

According to the latest figures from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Western Balkan route is by far the most used gateway into Europe for irregular migrants. It has become a corridor from Greece to Macedonia and then through Serbia to the borders of Hungary and Croatia.

Balkan countries are European countries, and the effects of the migration crisis make it an inherently European problem. This is why an overarching, comprehensive European strategy with well-thought-out supporting polices that call for a “collective” European response is needed. Western Balkan countries need to be players at the table because of their geography and the fact that their economies are too fragile to incur the political and economic costs of dealing with large numbers of refugees and migrants.

This point is made clear by the recognition that migration route governments and social services have been quickly stressed by the large numbers of migrants. The result has been a growing dissatisfaction with public policy and an increasingly negative public acceptance of refugees. The lesson, not to be lost, is that this crisis did not spring up as a result of a catastrophic natural disaster. Instead, it has been growing over several years in which European governments have failed to appreciate the magnitude of the problem and the need for a long-term strategy. There should be no illusion about the significance of the economic and psychological costs of this refugee crisis; they likely will be felt for a generation or more.

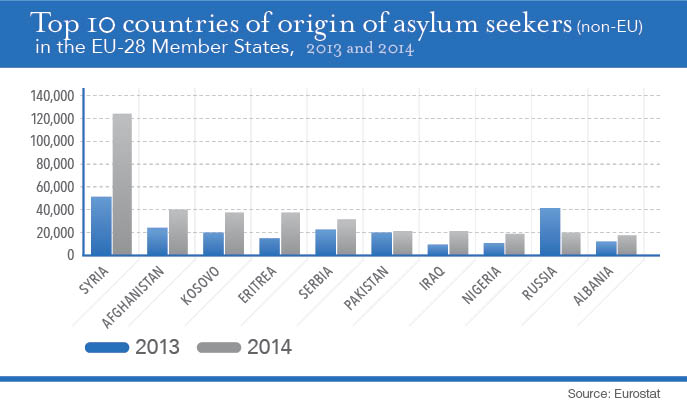

Complicating matters further, the Western Balkans is a major source of illegal economic migrants seeking jobs in EU countries. According to Eurostat data, Kosovo, Serbia and Albania have been among the top 10 countries of origin for those applying for asylum in the EU in the last three years. From January to October 2015, more than 130,000 irregular migrants from these three countries applied for asylum. For example, the total number of asylum seekers in Germany includes a staggering percentage from the Western Balkans. These numbers have risen to levels not seen since the 1990s. In 2014, the number of asylum seekers from the Western Balkans peaked at almost 110,000, compared to fewer than 20,000 in 2009. In 2012, there were almost 33,000 asylum applications submitted by Western Balkan citizens (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia) — 53 percent more than in 2011. This accounted for 12 percent of asylum seekers in Europe.

Complicating matters further, the Western Balkans is a major source of illegal economic migrants seeking jobs in EU countries. According to Eurostat data, Kosovo, Serbia and Albania have been among the top 10 countries of origin for those applying for asylum in the EU in the last three years. From January to October 2015, more than 130,000 irregular migrants from these three countries applied for asylum. For example, the total number of asylum seekers in Germany includes a staggering percentage from the Western Balkans. These numbers have risen to levels not seen since the 1990s. In 2014, the number of asylum seekers from the Western Balkans peaked at almost 110,000, compared to fewer than 20,000 in 2009. In 2012, there were almost 33,000 asylum applications submitted by Western Balkan citizens (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia) — 53 percent more than in 2011. This accounted for 12 percent of asylum seekers in Europe.

This has been the case for several years and deserves urgent attention. The cause is clear: Western Balkan migrants are economically motivated to escape from a region known for high levels of corruption, poor rule of law, and weak governance and institutions. The average annual income for a person in the Western Balkans is $5,300, less than a third of the EU average. As destination countries begin to close their doors because of political pressures, an increasing number of refugees and illegal migrants will be trapped in the transit countries of the Western Balkans. In a region that is already severely challenged economically, the impact of the refugee populations on the fragile existing infrastructure will be serious.

As large numbers of migrants become stalled in the Balkans, the potential grows for catastrophic political instability. It will produce one major outcome — more migrants and refugees. The other unmistakable fact that cannot be overlooked by European policymakers is that the next wave of refugees and migrants, like those in the past, will flow north. The EU must urgently act to develop a comprehensive long-term strategy that involves the Western Balkans.

Comments are closed.