In the autumn of 2015, the Marshall Center asked several alumni to share short, personal commentaries about how the migration challenge has played out in their countries. Views of the alumni — Ana Breben of Romania, retired Rear Adm. Ivica Tolić of Croatia, Maj. Bassem Shaaban of Lebanon, and Lt. Cmdr. Ilir Çobo of Albania — are featured. Their observations show that each country has been impacted differently by migrants. Refugees and displaced people make up a large percentage of people living in Lebanon, while Romania has remained largely immune to the crisis. Each of the four alumni recommends steps to meet the challenges ahead. A rough consensus emerges, including the need for a comprehensive approach with international cooperation and coordination. In terms of striking the right balance between security and human rights, all acknowledge the difficulty and a few reveal which, in their estimation, demands precedence. Here are Marshall Center alumni in their own words:

Ana Breben is a security expert in Romania specializing in national and transnational issues and security cooperation. She holds a bachelor’s degree in sociology from West University of Timisoara and a master’s degree in security studies. She is an alumna of the Marshall Center’s Program in Advanced Security Studies.

At the time of writing, in November 2015, Romania was not a destination country for migrants. It was not even a transit country. In fact, it has found itself in the special position where all major transit routes bypass it. But that does not mean Romanians are not aware of the acute migration challenge confronting most of our neighbors. People see and care about the human tragedies, but still somehow don’t feel directly affected. Even so, most are asking the same question as every other European: How much bigger could this get? Migration has always been a continuous and dynamic phenomenon, and sometimes it leads to crises. And you don’t have to be a specialist to understand that what is happening now might only be the beginning of a bigger influx of people coming from unstable regions neighboring Europe.

While not a destination or transit country, Romania has been a source country of migrants for some time. Romania suffered from a rough transition to a market economy, and the associated problems drove significant waves of citizens towards more developed countries. According to a Migration Policy Institute report, which draws on United Nations data, Romania is 15th in the world in terms of migrants’ country of origin (it is 108th in terms of migrants’ country of destination). Despite this, now seems to be a time when Romanians should pay attention to a possible reversal of paradigm, as masses of people on the move are gathering near our borders. Neighboring countries are starting to take drastic measures against this flow of people, and the risk of illegal crossings at Romanian borders is getting higher. Authorities should take steps to prepare, in addition to the traditional focus on border control. As it is a measure to gain Schengen accession, Romania is technically prepared to secure its borders.

The Romanian government has already taken some steps. It has been supporting countries on the “migration trail” such as offering humanitarian aid to Serbia, sending financial help to countries neighboring Syria, and sending police specialists to take part in joint investigation teams. The government has also worked on improving its legal framework. In fact, those migrants who manage to get legal status enjoy the same social and economic rights as all Romanian citizens, although they are drastically restricted in political and some civil areas. But many of them have real linguistic barriers. Romanian is an uncommon language, and some migrants have not even mastered English. And there are financial problems; state financial aid is very low, and an increase in the number of migrants would put great pressure on the social security system. They also have difficulties with bureaucracy and trouble accessing information about their rights. Unless they’ve had prior contact with Romania, most migrants seem to dream of moving to a more prosperous country.

Those migrants who remain in Romania usually say they find a friendly environment and complain about the same things the natives do. Surveys show that until November 2015, Romanians were not fearful of migration. Still, we need to take into consideration that migrants make up under one percent of the total population.

Romania’s next step should be to invest in education. To create unity, education is the right place to start. In fact, one of the main concerns of the few migrants in the country is the difficulty of learning Romanian if they are not lucky enough to live in a major university city. And without cultural unity, there is a risk of tension when people share the same space.

Over the long-term, integrating migrants might be a necessity for all European countries, including my own, and it only leads to more diversity and tolerance. But for that to happen smoothly, it is necessary for each country to establish fair and efficient integration policies and procedures, offer economic opportunities, and send a firm message against any form of extremism. As recent events have demonstrated, border security is not enough.

Rear Adm. (Ret.) Ivica Tolić is deputy head of the Guard Unites Veterans in Croatia and leads the Croatian Democratic Union defense subcommittee. He is retired from the Croatian Navy, where he served as chief of staff and deputy to the commander in chief of the Croatian Navy, and commander of the Southern Naval District and the Croatian Navy Fleet. He received his master’s degree from the Faculty of Economics at the University of Split and is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Senior Executive Seminar.

Rear Adm. (Ret.) Ivica Tolić is deputy head of the Guard Unites Veterans in Croatia and leads the Croatian Democratic Union defense subcommittee. He is retired from the Croatian Navy, where he served as chief of staff and deputy to the commander in chief of the Croatian Navy, and commander of the Southern Naval District and the Croatian Navy Fleet. He received his master’s degree from the Faculty of Economics at the University of Split and is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Senior Executive Seminar.

Human solidarity and humanitarian support are inherent to the Croatian people. We have shown that with our reception of refugees and migrants on several occasions. For example, during the 1990s, Croatia received more than 500,000 refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina, of which the largest number were Bosnian Muslims. All of them were temporarily accommodated in hotels on the Adriatic coast. They were recorded at the border, and illegal entry into Croatia’s territory was forbidden. At the same time, Croatia took care of about 280,000 of its citizens who were internally displaced, as well as 30,000 Croat refugees expelled from Serbia. This crisis took place during war, and those refugees and internally displaced people were at great risk of losing their lives.

Today, conflicts in North Africa and the Middle East have caused catastrophic destruction and damage. Migrants and refugees, seeing no visible termination of the conflicts on the horizon, have started to move toward Europe. They are organized and determined in their efforts to reach the wealthiest European Union countries. Earlier this year, the main migration route from Serbia led migrants to Hungary. Representatives of Croatian institutions said that Croatia was prepared and ready to receive migrants, if need be. This assertion of readiness proved inaccurate. In mid-September, after the border closed between Hungary and Serbia, more than 4,000 migrants per day were arriving in Croatia. Tovarnik, a small Croatian village near the border with Serbia, was flooded with migrants. It did not have any organized reception center or camp facilities with sufficient capacity. Migrants stayed at the railway station and on the streets. Improvised solutions were found but the scope of the crisis was underestimated and required more comprehensive preparation. At the time of writing (mid-October 2015), more than 160,000 migrants had passed through Croatia.

The fact that Croatia is not the final destination of the migrants at this point is to our advantage. However, Croatia must foresee that this may end. It remains possible, and moderately likely, that Germany will stop receiving migrants, and Hungary, Austria and Slovenia will close their borders. In such a case, what should Croatia do? We must also consider what Croatia should do if Germany and other EU countries return migrants who were registered here. This has been announced as an option. Finally, we must ask whether Croatia should accept the EU quota for asylum seekers, given the country’s fragile economic situation, large number of unemployed, and the problems of society in general that may have a negative impact on the “integration and employment” process.

The migrant challenge is not only a Croatian problem, and it has shown that the EU, as an entity, works only in theory. When faced with this challenge, the EU has been unable to find a common solution. At the time of writing, there had been no specific measures to address the crisis, and each member state has been taking an individual approach. The external border of the EU does not exist; there is no common security and defense policy, no common foreign policy, and no common policy toward migrants and asylum seekers. The combined joint naval forces of the EU in the Mediterranean are conducting solely search and rescue operations and are not protecting Europe’s external borders or implementing the Law of the Sea.

This approach motivates the migrants and does not stop their uncontrolled flow into Europe. Such practices and procedures, the absolute permeability of the external borders of the EU, the unimpeded passage through member states, and the “welcome policy” of some member states encourage migrants to risk moving to the EU. It is absurd that in some EU states the police are escorting the migrants and directing them to illegal border crossing points.

The EU is divided on the issue of migrants, and relationships among member states are fraying as a result. Each state sees the problem from its own perspective and is approaching it in accordance with national interests and policies. Some states see the crisis as primarily a security issue, while others see it primarily as a humanitarian one. The answer is certainly somewhere in between. We should not neglect the security aspect of migration issues but also need to remain humanitarian-minded. Laws and regulations related to migration policy and asylum cannot be ignored. The movement of migrants to their final destination has to be controlled and comply with international and national laws. Allowing the abuse of border crossings by individual states is reckless and could be dangerous.

The fundamental issues of the migrant crisis will have to be resolved beyond the EU’s external borders, at the origins of the crisis or as close to the origins as possible. There must be a common, long-term strategy for stabilization of the crisis areas of the Middle East and North Africa. The stabilization strategy must be comprehensive, leveraging political, diplomatic, economic and security tools. The EU must refrain from imposing solutions and must recognize that a single solution will not be applicable in all situations and scenarios. Countries neighboring the conflict areas must be helped as well.

In the short term, the inflows to Europe via the Mediterranean and Balkan routes will continue. In response, the EU must adopt a common strategy to address the migrant crisis. More decisive measures should be taken to protect the EU’s external borders. The joint force of the naval and police forces should switch its focus from search and rescue operations to protecting the EU’s external borders. All EU member states should comply with the Dublin Protocol. They should deny illegal border crossings and permit border crossings only at official border crossing points, in accordance with applicable procedures and in acceptable numbers. The same commitments should be requested from candidate countries for EU accession and countries with aspirations to become EU members. The EU must prioritize and solve the challenges of how to enhance its internal decision-making system, efficiency of administration, and common security and defense policies. European society has been divided over the migrant challenge, and consideration should be given to how to repair the damage.

At the national level, deportation proceedings should be activated against all migrants who have no grounds to seek asylum or refugee status. For those who have refugee status, they should be provided accommodations in refugee camps as a temporary solution until conditions for their return are met, or they should be transited to countries that will allow their permanent settlement. Each member state should organize task forces for migrant crisis response, capable of running 24/7 operations. The task forces should have representatives from the ministries of interior, defense, justice, finance, health, transportation and communications and also include some nongovernmental organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Events in Croatia over the past few months have shown the need to improve our assessment tools, including some institutional execution capabilities. Also, we have to improve coordination at the national level, with neighboring countries and at the EU level. This will require reorganization of the governmental system to enhance the decision-making process (fast-track decision-making), interagency collaboration and real-time information exchange.

Humanity and solidarity are positive principles that rest at the heart of European civilization. However, they should not be used to question the existing order, ignore legal obligations and suspend procedures. That would be a prelude to anarchy, which in its essence denies humanity and solidarity. State institutions must primarily protect the national interest, while respecting others and showing humane solidarity. The order of priorities cannot be inverted, because inversion would destroy the meaning of the state.

Maj. Bassem Shaaban has been an officer in the directorate of training for the Lebanese Armed Forces since May 2013. He coordinates foreign language instruction programs and facilitates relationships with Lebanese universities. Shabaan holds two bachelor’s degrees, a master’s degree in modern history and is pursuing a Ph.D. in modern history. He is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Security Sector Capacity Building course.

Maj. Bassem Shaaban has been an officer in the directorate of training for the Lebanese Armed Forces since May 2013. He coordinates foreign language instruction programs and facilitates relationships with Lebanese universities. Shabaan holds two bachelor’s degrees, a master’s degree in modern history and is pursuing a Ph.D. in modern history. He is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Security Sector Capacity Building course.

The Republic of Lebanon is one of the smallest countries in the Middle East and in the entire Arab world. The Lebanese population also is one of the smallest, at close to 6 million. In spite of its size, the Lebanese community is unique in the Arab world for containing 19 ethnicities.

Since its independence in 1943, Lebanon has hosted refugees of various nationalities —mainly Armenians, Kurds and Palestinians. By the beginning of the 21st century, refugees also arrived from Iraq and especially Syria.

The situation in Lebanon is growing more critical because of instability in the Middle East. This instability is widening and its influence is touching more countries in the region.

Since February 2011, a bloody struggle has been taking place in Syria, causing mass displacements of Syrians from the hot zones to neighboring countries. The official Lebanese position was “No Interference,” and the country took measures to allow only civilians to cross its borders. If a fighter wants to cross, he or she must disarm and abandon all military activities.

The Lebanese authorities have been dealing with displaced Syrians on a humanitarian basis, supplying them with basic needs, such as food, medical services, educational services and utilities. Most importantly, Lebanon has provided them with a safe place to live. But the conflict in Syria has persisted beyond expectations, causing hundreds of thousands of displaced people to spread all over Lebanon, adapting to the new situation and making a living where they now reside.

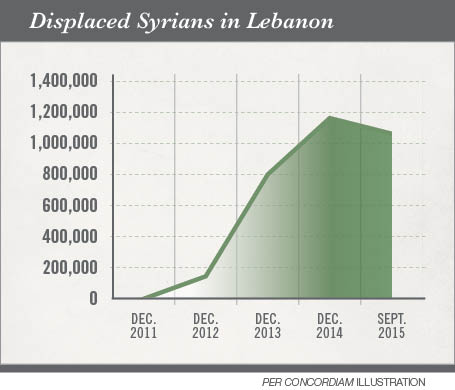

The number of displaced Syrians in Lebanon is increasing year by year, and the following chart clearly shows this rise:

The numbers above were assembled by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, but they do not include those who crossed the borders illegally and did not register as displaced. By the end of September 2015, this augmented number of refugees and displaced people represented a large percentage of the Lebanese population. Hosting such a large number of foreigners normally creates challenges, if not threats, to the hosting society. Lebanon is experiencing this.

The numbers above were assembled by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, but they do not include those who crossed the borders illegally and did not register as displaced. By the end of September 2015, this augmented number of refugees and displaced people represented a large percentage of the Lebanese population. Hosting such a large number of foreigners normally creates challenges, if not threats, to the hosting society. Lebanon is experiencing this.

These huge numbers are beyond the capacity of the Lebanese authorities to manage. The international community has played a supportive role, but despite all the donations and aid, the gap between what has been provided and what is needed is still wide.

The main concern is how to maintain stability while respecting human rights. Early on, Lebanon faced several security incidents and a significant increase in crime, including suicide bombings, murder and robbery. Overall, however, the security situation stayed under control. This changed on August 2, 2014, when terrorists of the Al-Nusrah Front and ISIS attacked the border town of Arsal, 120 kilometers from Beirut. Terrorists entered the town and killed civilians. They also kidnapped members of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and the Internal Security Forces (ISF).

Many of the attackers crossed the Lebanese-Syrian border, but most came from Syrian displacement locations within Lebanon itself. The LAF launched a rapid counterattack and drew the terrorists out of town to the border area, but the price was heavy with 19 killed and 28 kidnapped.

In spite of this high price, not a single act of revenge occurred. The LAF and the ISF continued practicing their duties normally with one single concern: “Stability must be restored and maintained to protect all residents, including the displaced Syrians.” For this purpose, the LAF has put more effort into keeping the terrorists away from the displaced civilian Syrians by:

Closing all illegal crossings on the Lebanese- Syrian border.

Conducting continuous search operations in the gathering locations, seeking wanted individuals and arms.

Keeping an eye on suspicious intentions.

On the other hand, the LAF has considered the basic needs of the displaced Syrians and tried to support them under the purview of Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC). The CIMIC Directorate, operating under the LAF Army Staff for Operations, made great efforts to build a good relationship with the displaced, especially those who live in gathering places around Arsal.

CIMIC has provided the displaced with food rations, winter clothes for the children, and books and stationery for students. CIMIC has also provided medical equipment to the Ministry of Social Affairs to benefit the displaced and helped deliver aid in extreme weather, such as the Alexa storm of 2013. This positive relationship has helped maintain order at refugee gathering locations without the use of force.

To control the number of displaced Syrians and distinguish the real displaced from the fake ones, the Lebanese government, since June 2014, has decided that any Syrian who returns to Syria cannot re-enter Lebanon as a displaced person. Instead, he or she can only re-enter as a visitor and must clearly state the purpose of the visit with all necessary legal documents.

In spite of its small size, population and limited resources, Lebanon will continue to defend freedom and human rights without neglecting internal stability. According to the famous statement of Pope John Paul II: “Lebanon is more than a country; it is a message.”

Lt. Cmdr. Ilir Çobo is a patrol craft commanding officer in the Albanian Naval Force. For 12 years he was directly involved in maritime operations, including Coast Guard duties and law enforcement. He holds a master’s degree in advanced maritime science from the Ismail Qemali University of Vlora in Albania and is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Program on Countering Narcotics and Illicit Trafficking.

Lt. Cmdr. Ilir Çobo is a patrol craft commanding officer in the Albanian Naval Force. For 12 years he was directly involved in maritime operations, including Coast Guard duties and law enforcement. He holds a master’s degree in advanced maritime science from the Ismail Qemali University of Vlora in Albania and is a graduate of the Marshall Center’s Program on Countering Narcotics and Illicit Trafficking.

Suard Alizoti is a professor in the nautical sciences department at Ismail Qemali University of Vlora in Albania. His former positions include gunnery and torpedo officer and planning and operational officer in the Inter-Institutional Maritime Operational Center of Albania. He is a graduate of the Naval Academy of Livorno and holds a master’s degree in maritime and naval sciences from the University of Pisa in Italy.

Suard Alizoti is a professor in the nautical sciences department at Ismail Qemali University of Vlora in Albania. His former positions include gunnery and torpedo officer and planning and operational officer in the Inter-Institutional Maritime Operational Center of Albania. He is a graduate of the Naval Academy of Livorno and holds a master’s degree in maritime and naval sciences from the University of Pisa in Italy.

The issue of migration, and particularly that of Syrian migration, is on the agenda of Western Balkan countries. Macedonia, Serbia and Albania are affected by the large migratory wave from the Middle East, and the triangle among these countries remains the main transit area for migrants taking the eastern route to Europe. Public debate has been quite emotional, running the gamut from solidarity to rants driven by a self-protection instinct.

Although still not de jure, the Western Balkans region is an integral part of the historical, geographical, social and cultural reality of Europe. The difficulties and challenges facing the Western Balkans and EU countries as a result of mass migration are fundamentally the same. However, problems in this part of Europe are more complex. Regional stability has often faltered, and conflicts with territorial, nationalist and racist origins have erupted. Combined with ethnic, social, political and economic issues, these conflicts have continuously produced flows toward Europe, transforming the Western Balkan countries into a permanent source of migration. There have also been noteworthy migrant flows between countries in the region. During the conflict in Kosovo in 1999, for instance, Albania and Macedonia were impacted; about 800,000 ethnic Albanians from Kosovo went to Albania while thousands more went to Macedonia.

Countries in the Western Balkans have concurrent, multiple roles when it comes to migration: They are transit countries as well as host and source countries. This has given them experience managing the humanitarian crises and problems that come with migratory flows. Despite the systemic weaknesses of these countries, the philosophy and instruments adapted by the region have proven to be relatively effective in countering threats to security as well as guaranteeing human rights.

At the moment, the number of Syrian refugees in the Western Balkans is still manageable and the regional security situation cannot yet be considered vulnerable. The increasing tendency to interrupt this flow with walls and wire fences is neither efficient nor humane. The force of desperation driving these migrants cannot be stopped by wire fences or walls. To discourage the movement of people without providing a substantial solution is simply killing hope, faith and freedom, and does not guarantee security. This degradation of the already-chaotic situation makes the countries affected vulnerable to xenophobia, organized crime and terrorism. The only beneficiaries of a blockade of the migrants are the traffickers who exploit every opportunity for profit, while the migrants themselves experience additional difficulties.

Migration is not new, and it will not go away so long as there are discrepancies in welfare and security across countries and societies. Managing the migration phenomenon will be one of the most demanding challenges that lie ahead. To better deal with this reality, which sooner or later could involve all of Europe geographically and politically, the causes and consequences of migration should be treated and managed. There needs to be a durable solution involving Europe as well as countries of origin.

European countries have sufficient energy, tools, assets and the appropriate experience to effectively manage the crisis. However, the implementation of an effective and strategic approach is above all a political issue. Policy should be inspired by solidarity and the philosophy and basic values of the EU. Europe must assume its responsibilities and become the decisive factor in solving the problems of the Islamic world. Bridges of trust and collaboration between civilizations should be rebuilt, and peace should be restored in the Middle East. Europe should make great efforts to ensure that Muslims, wherever they come from, may find a future in their homelands. On its own soil, Europe should integrate migrants, who represent real potential for development. At the same time, Europe must reinforce the instruments of border control. Above all, Europe has to get involved for the definitive elimination of terrorist threats.

Coordination among concerned countries of the Western Balkans and with international stakeholders is needed. The Balkan states are a natural part of the European continent. Cooperation is needed to unify political will and synchronize the instruments of state security. Albania, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Macedonia have the obligation to deepen their partnership to guarantee common development on a European course. These countries must transform from being consumers of security into producers of security. Isn’t this a key criterion for integrating the region into the EU?

The challenge of balancing security and human rights is daunting, but many successful leaders have said: “We have been in a situation where we had two paths to choose between. We chose the most difficult path, and it was also the right one!” This is exactly what must happen today. Migrants need humane treatment, and this should be a priority of the entire civilized world.

Comments are closed.