Terrorists rarely exploit refugee networks to conduct attacks

By Dr. Sam Mullins, Marshall Center

In October 2014, RT news reported that “U.S. intelligence sources” had “unencrypted locked communications of the caliphate’s leadership,” revealing that “Islamic State militants [were] planning to insert operatives into Western Europe disguised as refugees.” Fears of this alleged Islamic State (IS) Trojan horse strategy intensified in January 2015 after a self-confessed smuggler for the group, operating in Turkey, claimed to have sent 4,000 IS fighters to Europe by loading them onto cargo ships filled with refugees. The intent, he asserted, was to stage attacks in retaliation for coalition airstrikes. The following month, an article published online by another professed IS member, apparently based in Libya, advocated infiltrating Europe using immigrant boats from North Africa.

As the number of refugees has continued to rise, so, too, have security concerns. By October 2015, the number of Syrian refugees was estimated at about 4 million, and although most of them are in Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon or Turkey, many thousands are now making their way to Europe. Three-quarters of a million migrants and refugees (about 40 percent from Syria) had already arrived, placing a tremendous strain on the nations concerned and further stoking fears of terrorism. Meanwhile, although the United States has so far pledged to take in just 10,000 Syrian refugees, a September 2015 U.S. Homeland Security Committee report expressed concern that those admitted to Europe will eventually gain passports that will enable easy trans-Atlantic travel, thus potentially allowing terrorist “sleeper cells” to enter the country.

Fears that terrorists are deliberately infiltrating refugee flows further escalated in the wake of the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris. At least two of the attackers are believed to have entered the European Union via Greece, posing as asylum seekers. Given how closely these issues appear to have become enmeshed in the media and the minds of politicians, security professionals and the public, it is important to assess the threat of terrorism objectively as it relates to mass migration. This article begins with an examination of the historical track record, drawing on data from my book “Home-Grown” Jihad: Understanding Islamist Terrorism in the US and UK. This is followed by a discussion of more recent developments and implications for counterterrorism.

The Historical Record

As Daniel Byman pointed out in an October 2015 Lawfare article, “[t]errorism and refugees share a long and painful history.” In the context of the West, the gradual rise of homegrown jihadist terrorism is at least partly tied to the growth of immigrant diaspora populations, many of whom have fled from conflict and persecution in their countries of origin. In the 1990s, following the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, jihadists from the Middle East and North Africa, many of whom were unable to return home, took advantage of the situation to expand operations in Europe and North America. Influential jihadi preachers, fundraisers and facilitators were able to claim asylum and then use the opportunity to recruit and expand their networks within the host countries. Notable examples included Abu Qatada in London, Sheikh Anwar al-Shabaan in Milan, Abdul Rahman Ayub in Sydney and Mullah Krekar in Norway. Numerous jihadi terrorists affiliated with groups such as the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and the Algerian Armed Islamic Group also came to the West posing as asylum seekers. For the most part, they served in various nonviolent support roles; however, some planned and conducted attacks. The most notorious of these was Ramzi Yousef, who arrived at JFK Airport in New York City in September 1992, promptly filed for asylum and was allowed into the U.S. Four months later, assisted by locally-recruited accomplices, Yousef fulfilled his aim of bombing the World Trade Center before fleeing the country.

Changes in the global jihadi landscape have been reflected to varying degrees in the militant activities of different diaspora populations in the West. For instance, since the end of the war in Algeria, fewer Algerians have become involved in jihadi terrorist activity in the United Kingdom. Yet, as Pakistan took on greater significance for groups like al-Qaida and the Taliban, larger numbers of British-Pakistanis have turned to terrorism, and a similar pattern has unfolded in Canada. Meanwhile, in the U.S., about two-dozen Somalis, several of whom were refugees and at least four of whom became suicide bombers, returned to Africa to fight for al-Shabaab after the invasion of Somalia in 2006.

It is clear from the historical record that mass migration, and the flow of refugees in particular, have in a very broad sense facilitated the spread of jihadi terrorism, and at times have been directly exploited by terrorists seeking safe haven, new opportunities and access to intended targets. However, these observations, by themselves, are potentially misleading. To get a more accurate sense of the relative threat posed by the intersection of mass migration and terrorism, it is necessary to examine the number of “refugee terrorists” relative to the overall number of refugees and the overall number of terrorists.

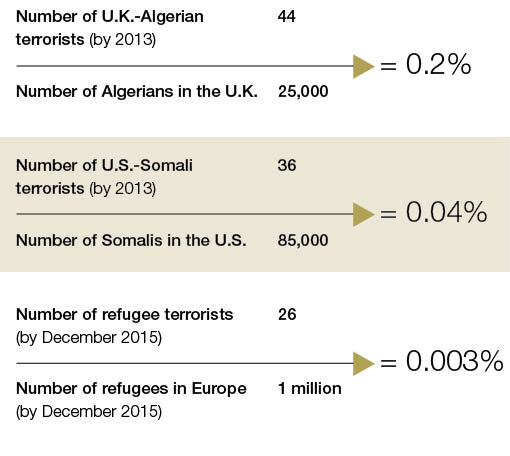

Regarding the former, the example of Algerians in the U.K. is illustrative. Prior to the 1990s, relatively few Algerians lived in Britain, but by 2004 the estimated number had risen to between 25,000 and 30,000, according to a study by the Information Centre about Asylum and Refugees in the U.K. By comparison, just 44 Algerians are known, with some degree of certainty, to have been involved in terrorist activity in the U.K. between 1980 and 2013. This works out to less than 0.2 percent of the British-Algerian population. The 2010 U.S. Census estimated the country’s Somali-born population at about 85,000, yet only 36 were involved in terrorism up until 2013, working out to 0.04 percent. If these examples are representative, we can expect far less than 1 percent of the current wave of refugees to become involved in terrorism.

It is also apparent that the vast majority of jihadi terrorists operating in Western countries did not arrive as refugees. For example, data I have compiled on jihadi terrorism indicate that 15 percent of jihadi terrorists who became active in the U.K. prior to 2013 arrived as asylum seekers or refugees. In the U.S., it is just 5 percent. In these cases, “refugee terrorists” are clearly the minority. Moreover, during the same time, 48 percent of British and 61 percent of American jihadis came from abroad, as opposed to being born in these countries. These disparities clearly demonstrate that claiming some form of refugee status is not a particularly common method of entry to the West for jihadi terrorists. Indeed, the historical record suggests that terrorists who come from abroad are more likely to enter a given country using a valid visa.

Furthermore, several future jihadi terrorists who did come to the U.K./U.S. as refugees originally did so as children traveling with their families or were otherwise legitimate claimants at the time they completed the application, only to radicalize later on. They did not, therefore, deliberately infiltrate mass migration flows to conduct acts of terrorism. In many respects they were homegrown terrorists. The Tsarnaev brothers, who had been living in the U.S. for 10 years before they bombed the 2013 Boston Marathon, are a case in point. In fact, as documented in my book, the average length of time spent living in the West for foreigners who became jihadi terrorists after 9/11 was 9.1 years in the U.K. and 10.7 years in the U.S. Although those who claimed asylum typically became involved in terrorism sooner than this — with respective averages of 1.8 and 5.3 years after entering the country — the fact remains that relatively few jihadi terrorists have entered the West disguised as asylum seekers with the pre-existing intention of committing acts of terrorism. Instead, they are far more likely to be radicalized while living in a Western country and almost as likely, if not more so, to be born there.

In sum, recent history suggests that although mass migration and terrorism are indeed connected, refugee terrorists are the exception to the rule. They have accounted for a small minority of jihadi terrorists operating in Western countries. Those who did come as refugees were not necessarily involved in terrorism before they arrived; cases such as Ramzi Yousef have been exceptionally rare, while the evidence for “sleeper cells” is close to nonexistent. The only clear example of this was Ali Saleh Kalah al-Marri, sent to the U.S. by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in September 2001 (although notably, he was in possession of a valid student visa). Altogether, refugee terrorists represent an infinitesimal fraction of the total number of refugees who have come to the West from jihadi conflict zones. Nevertheless, history can only tell us so much. It is therefore necessary to re-examine the threat in light of more recent developments.

Recent Developments

The current instability in Syria and Iraq and the rise of IS have undoubtedly been game-changers for the “global Salafi jihad,” with 30,000 jihadist foreign fighters from about 100 countries making their way to the conflict zone, coupled with a significant uptick in terrorist plots and attacks. When viewed in light of IS’ various threats against the West and the fact that many foreign fighters are already believed to have returned home, the inescapable conclusion is that the terrorism threat has increased substantially. However, the question here is whether the threat has increased as it relates specifically to the flow of refugees.

From May to October 2015, only three cases were reported in detail involving alleged jihadi terrorists “disguised” as refugees. However, the first of these cases now appears to have been discredited, while there are still questions relating to the remaining two. In May 2015, Italian police arrested Abdel Majid Touil, a young Moroccan suspected of playing a role in the attack on the Bardo National Museum in Tunis in March. Touil journeyed to Italy among a boat full of refugees from Libya and was tracked down and apprehended after his mother reported his passport missing, according to the Guardian. However, he was in Italy before the attack took place and the case against him appears to have collapsed, with Italian authorities dropping the investigation and refusing to extradite him due to lack of evidence.

In August 2015, German police acting in collaboration with Spanish authorities arrested another Moroccan named Ayoub Moutchou at a residence for asylum seekers outside Stuttgart. As an alleged recruiter for IS who had been living in Spain, Moutchou was described by The Associated Press as “a key element in communications between the group’s members in Iraq, Syria and Turkey and sympathizers in Europe, [who] had begun making contacts aimed at carrying out attacks.” However, it has not been confirmed that Moutchou originally entered Europe along with refugees or that he personally held refugee status. The third case involved a Tunisian named Mehdi Ben Nasr, who had been convicted of terrorism offenses in Italy and was deported in April 2014. According to The Washington Post, he attempted to re-enter the country on a migrant boat, which landed at Lampedusa on October 4, 2015, but was identified and expelled a week later. His case is perhaps the clearest example of a refugee terrorist to date, although his reasons for returning to Italy are unclear and, in any case, he was unsuccessful.

In addition to these cases, a number of prominent officials have asserted that jihadists are indeed posing as refugees to enter Europe. For instance, in July 2015, Michèle Coninsx, the EU’s top prosecutor, told the press that she had received information that migrant boats to Europe were carrying IS fighters as well as refugees. More recently, The Telegraph reported that German authorities are investigating 10 cases of refugees accused of taking part in terrorism or war crimes. Refugees suspected of ties to terrorism have since been arrested in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, the Netherlands and Finland, while another was shot dead during an attempted attack in France. However, the most damning evidence so far is the aforementioned discovery that two or more of the Paris attackers came to Europe disguised as refugees. If this is verified, it would seem our worst fears have become reality. Yet, we should not let the gravity of an incident shape our understanding of the probabilities involved. The evidence thus far is summarized in the table below.

The “refugee terrorist” threat: historical and contemporary examples

While hardly voluminous, recent examples seem to confirm that some jihadi terrorists are exploiting the current mass migration crisis to enter or move around within Europe, and of course the consequences of this may be dire. Nevertheless, in the context of now more than 1 million migrants, many from Syria and other places of concern, the number of refugee terrorists discovered so far has been minimal. To further gauge the level of threat, it is useful to examine the recent wave of jihadist terrorism plots and attacks in the West. According to Thomas Hegghammer and Petter Nesser, writing in Perspectives on Terrorism, from 2011 to June 2015 there were 69 such plots, 30 of which were inspired by or in a very small number of cases linked to IS, and 19 of which (28 percent) were executed. More revealingly, just 16 plots (23 percent) involved foreign fighters and only 11 of these individuals had been to Syria, a “blowback rate” of just 0.3 percent (1 of 360) of the estimated 4,000 Europeans who have gone to the region. While the assault on Paris in November 2015 demonstrated the potential impact such attacks can have, it has not drastically altered the quantitative assessment.

While hardly voluminous, recent examples seem to confirm that some jihadi terrorists are exploiting the current mass migration crisis to enter or move around within Europe, and of course the consequences of this may be dire. Nevertheless, in the context of now more than 1 million migrants, many from Syria and other places of concern, the number of refugee terrorists discovered so far has been minimal. To further gauge the level of threat, it is useful to examine the recent wave of jihadist terrorism plots and attacks in the West. According to Thomas Hegghammer and Petter Nesser, writing in Perspectives on Terrorism, from 2011 to June 2015 there were 69 such plots, 30 of which were inspired by or in a very small number of cases linked to IS, and 19 of which (28 percent) were executed. More revealingly, just 16 plots (23 percent) involved foreign fighters and only 11 of these individuals had been to Syria, a “blowback rate” of just 0.3 percent (1 of 360) of the estimated 4,000 Europeans who have gone to the region. While the assault on Paris in November 2015 demonstrated the potential impact such attacks can have, it has not drastically altered the quantitative assessment.

Therefore, although these figures are not the final word on the subject and do not pertain to refugees specifically, they do tell us that, to date, of the hundreds of European foreign fighters who have returned from Syria and Iraq, relatively few have been involved in planning or conducting terrorist attacks at home. In fact, the quantitatively greater threat has come from radicalized groups and individuals who have not experienced training or combat overseas. The terrorism threat associated with returning foreign fighters disguised as refugees or otherwise is undoubtedly greater in terms of potential impact; however, it is of relatively low probability, at least in the short-term.

Given that domestic jihadi terrorists have been responsible for the majority of recent plots in the West, an arguably more likely scenario is that refugees from Syria and elsewhere will be targeted for recruitment by Western extremists after they arrive, rather than traveling with the pre-existing intention of committing acts of terrorism. Indeed, Holger Münch, head of the German Federal Police, told The Telegraph that he had received reports of “around 40 attempts at contact from Salafists who wanted to recruit young refugees.” Emphasizing the potential risk, he further elaborated that there is a danger “that young men whose hopes are not fulfilled in Germany will eventually join Salafist groups, get taken in by their ideologies, become radicalized and commit violent acts.”

Reasons not to overreact

Although by no means inevitable, refugee populations may be particularly vulnerable to radicalization and recruitment to terrorism, given their inherently marginalized and difficult situation. Sadly, and somewhat ironically, the level of risk is being exacerbated by right-wing extremists who are responsible for an increasing number of violent attacks against refugees. Such actions play directly into the “us versus them” narrative promoted by jihadist recruiters, who will be only too happy to receive the victims with open arms. As Byman succinctly puts it, the “danger is that radicalized European Muslims will transform the Syrian refugee community into a more violent one over time.”

It seems that IS is more concerned that refugees will become successfully integrated into life in the West. This was made abundantly clear in September 2015, when the group released 14 videos over three days warning Muslim populations not to emigrate to the Dar al-Harb (“land of war” or disbelief), instead urging them to stay and join the “caliphate.” As Aaron Zelin has pointed out, “the migrant flow [to Europe] is anathema to ISIS, undermining the group’s message that its self-styled caliphate is a refuge.” Furthermore, IS is chiefly concerned with events inside their territory. Given how important sheer manpower is to their ability to take and hold ground, why would IS send away skilled fighters in large numbers to carry out attacks that can be left to sympathizers who are already in the West, at no cost to the organization? Indeed, as they come under increasing pressure, it appears that IS has established specialist units to prevent and deter potential deserters, according to an October 2015 article in The Telegraph. And, according to multiple news sources, it seems they are becoming increasingly reliant on the recruitment of child soldiers, as well as gradually accepting female combat roles.

It would also make little sense for terrorists to deliberately draw attention to tactics that are clearly best kept secret. The case of the IS smuggler interviewed in January is telling. Not only had he apparently received permission to disclose his activities to the press, but also claimed to have sent an unfeasibly large number of fighters to the West. It is clearly in IS’ interests to exaggerate the threat associated with refugees for multiple reasons, not the least of which is that it magnifies its own perceived reach and capability, increases Western opposition toward accepting refugees and enables them to present the caliphate as an attractive alternative. All of this calls into question the credibility of the Trojan horse strategy, given that IS’ No. 1 priority seems to be to attract people to its territory, rather than send them away.

Of course, the November 2015 attacks in Paris, for which IS has claimed responsibility, potentially weaken this line of argument. As noted above, prior to November, most plots or attacks attributed to IS were inspired by the group rather than directly supported or controlled by them. The Paris attacks, if indeed directed by IS, seem to represent a shift in strategy indicating a greater willingness to invest resources toward attacking the West. In other words, IS now seems to be putting its money where its mouth is. Even so, this does not alter the fact that the vast majority of refugees are simply not terrorists. Even if every single IS fighter (perhaps as many as 30,000 according to some estimates) were to come to the West disguised as refugees, they would represent little more than 4 percent of recent migrants to Europe. Such a scenario is less than plausible.

Despite the hysteria about IS infiltrating refugee populations, the evidence so far has been scant, and there is ample reason to believe that jihadists and right-wing politicians alike are exaggerating the threat to further their own interests. The greater danger appears to be the potential radicalization and recruitment to terrorism of small numbers of refugees over the mid- to long-term (i.e., after they have arrived), which may be facilitated by Western-based jihadists and exacerbated by the actions of right-wing extremists. This is not to say that no jihadi terrorists will take advantage of the current crisis to slip undetected into the West. But such cases are likely to remain relatively rare.

Implications for Counterterrorism

Both historical and more recent events clearly demonstrate that refugees coming from jihadi conflict zones are not primarily a concern for counterterrorism and are far more appropriately viewed as humanitarian, economic and political challenges. Terrorists in this context are very much the proverbial needle in a haystack. However, this does not mean they can be ignored. The screening of refugees upon arrival in the EU, though not entirely ineffective, remains woefully inadequate. Their transit from countries like Greece and Italy to Germany or elsewhere is often chaotic and poorly managed, and recipient nations are struggling to provide accommodation and other basic services. From a counterterrorism perspective, there is clearly a need to improve the collection, processing and sharing of refugee information upon their arrival. For example, the above mentioned Homeland Security Committee report notes the need to improve capabilities for checking fraudulent passports and for front-line access to Interpol databases. The subsequent transit and resettlement of refugees must also be monitored more effectively. However, despite some progress, the sheer scale of the crisis and limitations in resources and funding — not to mention unproductive bickering between nations — mean there are no obvious near-term solutions for the practical, technological and financial difficulties involved.

Given this reality, counterterrorism resources are perhaps best invested in developing human intelligence sources within smuggling networks in source or “hub” countries such as Turkey, as well as at key reception and transit points within Europe where organized criminals and extremists are known to operate. Sharing such intelligence between relevant nations and agencies will enhance the chances of detecting potential terrorists. Unfortunately, information sharing on these issues, though improved, remains a perennial challenge. For instance, the closest thing to a global foreign fighter database that exists is maintained by Interpol, but according to the Homeland Security Committee, as of September 2015, it included just 5,000 names from an estimated 25,000-30,000 suspects worldwide. Improved information sharing is therefore arguably the greatest and most fundamental counterterrorism priority.

Another task for security services relates to the resettlement of refugees. As noted above, they may be particularly vulnerable to radicalization, and European extremists have already attempted to recruit them. Monitoring and disrupting these activities is vital. Likewise, authorities must maintain a close eye on right-wing extremists, allocate sufficient resources to protect refugees from attacks and aggressively pursue prosecutions where appropriate. Combined, these measures will help reduce the risk of radicalization and terrorist recruitment within host nations, particularly where there is efficient short- and long-term provision of social, health, information and other services that are necessary for resettlement and reintegration.

Although counterterrorism authorities clearly have a role to play in handling the influx of refugees to the West, it must be reiterated that this is not primarily a counterterrorism problem. It is crucial that this is communicated effectively to all relevant stakeholders, including politicians, policymakers, security officials, and not least of all, the media and the public at large. Gaining a more accurate understanding of the links — or relative lack thereof — between mass migration and terrorism in the West will help inform decision-makers while simultaneously defusing fear-mongering that is making the situation worse.

Finally, given that jihadi terrorists are generally not entering the West disguised as refugees, we must gain a more systematic understanding of how they are doing so. Many, it seems, are using legitimate passports. If indeed this is the case, it speaks yet again to the need for more effective information sharing on terrorism suspects, monitoring the travel of Western citizens, canceling travel documents when necessary and strengthening border controls, all balanced against the need to protect civil liberties.

The good news is that despite many gaps in Western security and a significant increase in jihadi terrorism in recent years, the success rate in countering the threat remains impressive. As alluded to earlier, foreign fighters are far more likely to be known to security services compared to “freelance” or “lone actor” terrorists, who are relatively isolated from broader extremist networks. And, although such individuals have been responsible for the majority of attacks in the West, they are also generally lacking in capability. No one should be complacent, yet we should not forget that contrary to popular belief, the odds are ultimately stacked in our favor, not that of the terrorists.

Comments are closed.