Countering Beijing’s Regional Influence

By Dr. Valbona Zeneli, Marshall Center professor, and Fatjona Mejdini, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

China’s footprint in the Western Balkans has significantly expanded over the past decade, in line with the diplomatic trade and investment objectives of Beijing’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) strategy, later renamed the Belt and Road Initiative, and within the strategic context of wider China-European Union relations. A key tool in promoting engagement in the region, especially with the five Western Balkans countries (excluding Kosovo), has been the 16+1 initiative. Established in 2012, and later linked to OBOR, the 16+1 is an economic cooperation initiative between China and 16 Central and Eastern European countries that promotes OBOR, similar to other Chinese market penetration strategies in other regions of the world. It later grew to 17+1 with the addition of Greece in 2019, but Lithuania has dropped out and it is again 16+1. This regional platform, which brings together a diverse group of countries (11 EU and five non-EU countries) from the Baltics to the Balkans, is concentrated in three main areas: trade, investment and transportation.

16+1 supports Beijing’s diversified strategy in Europe by allowing it to focus capital investments on strategic assets and new technologies in core EU countries, complemented by large infrastructure projects on its periphery. China’s investment strategy appears to be tailored differently for different European countries, depending on economic wealth, technological advancement, geographical location and institutional framework. In the Western Balkans, Beijing is using a hybrid approach to gain influence, combining elements of infrastructure projects that we see in developing countries and economic interactions, similar to those in other EU countries.

The reasons for China’s growing interest in the Western Balkans are manifold. First, the region’s geostrategic position makes it a perfect gateway to EU markets and a key transit corridor for OBOR. Second, Chinese interests in the region are strongly related to infrastructure projects and privatization opportunities, where demand for preferential lending is high and acquisition prices are low. Third, Beijing is searching for new markets to expand its exports and trying to gain control of strategic assets in the EU’s front yard. Fourth, Chinese companies are securing access to natural resources and focusing on strategic sectors, such as energy, mining and mineral processing. Fifth, Beijing wants to increase its influence and deepen its economic and diplomatic presence in the region because of its proximity to the EU and as a counterbalance to the region’s trans-Atlantic relationship.

In the Western Balkans, as in other regions of the world, Beijing is cultivating an image of itself as a benign global power, a credible source of economic development, and a ready and reliable partner looking for opportunities to invest in strategically important sectors. Its official narrative emphasizes the mantra of mutually beneficial economic interaction. This narrative raises expectations of its ability to bring wealth to the region while directing attention away from politics.

A short history

China is not a newcomer to the region. While Albania and the countries of the former Yugoslavia have had diplomatic, economic and cultural ties with Beijing for decades, in recent years China has been laying the groundwork for a long-term, multifaceted and ever-deeper presence in the Western Balkans. In its geopolitical narrative, Beijing deliberately highlights themes of “traditional friendship” and “shared past,” focusing on the region’s socialist past and the lingering degree of post-communist nostalgia.

The diplomatic relationship between China and Albania officially began in 1949 and grew stronger based on a shared communist ideology. The split of Enver Hoxha’s communist Albania from the Soviet Union in the early 1960s opened the way for a stronger and exclusive relationship with Mao Zedong’s China. Those years were characterized by multidomain cooperation between the two countries, as Beijing became an isolated Albania’s main supporter. During this period, China provided large loans for heavy and military industries, especially arms and ammunition. In an important 1961 agreement, China pledged technical support to Albania to build industrial plants and factories (chemical, food, clothing, construction materials, steel mills). Trade volume between the two countries increased as Albania exported raw materials (oil, chrome, copper) and imported mainly industrial products and pharmaceuticals. Strong cultural links were developed during two decades of intensive friendship, but in 1978 the relationship fell apart over ideological disputes. Albania isolated itself from the rest of the world until 1991. Its relationship with China never returned to historic levels.

The Sino-Yugoslav diplomatic relationship was vibrant during the 1960s and 1970s and became even closer after the breakup between Beijing and Tirana. In 1977, Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito visited China for the first time, followed by a return visit of Chinese Prime Minister Hua Guofeng to Belgrade in 1978. Ties were further strengthened in the mid-1990s, when internationally isolated former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević found an ally in faraway China and opened the door for the first Chinese migrants to Serbia. The alliance was further forged politically during the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, when an errant bomb partly destroyed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese journalists. Today, Serbia considers China a strategic partner and has become the biggest beneficiary of Chinese investments in Southeastern Europe.

China-Western Balkans trade

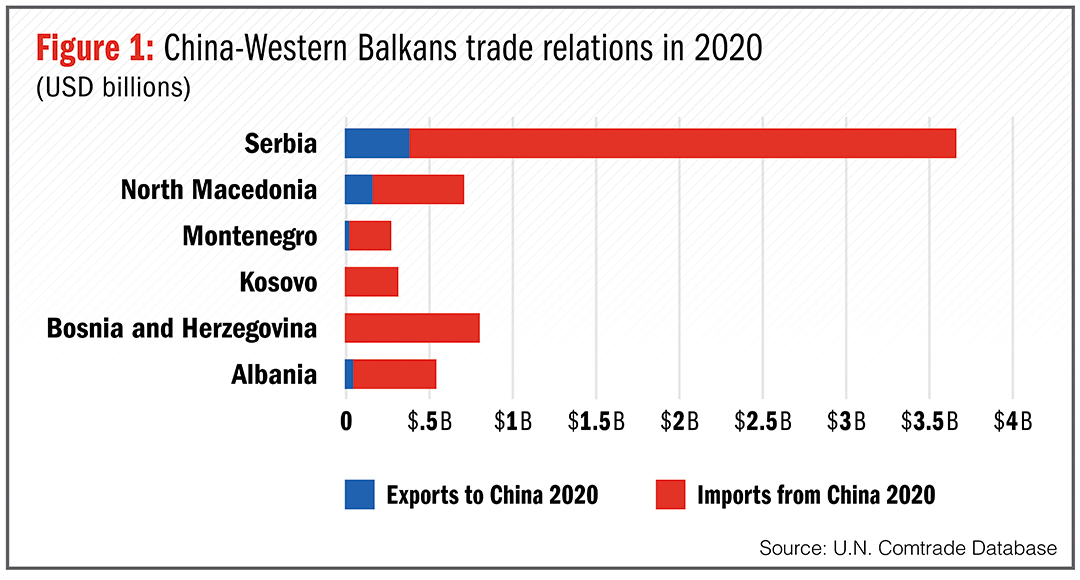

Trade relations between China and the Western Balkans have increased rapidly over the past decade. While the EU remains the region’s main trade partner, with over 70% of the total trade volume, China has become the region’s second- or third-most important trade partner. Considering the small market of the Western Balkans (including Kosovo), trade exchanges reached $6.3 billion in 2020, according to the United Nations Comtrade Database. (See Figure 1) Nearly 60% of this trade was conducted with Serbia ($3.7 billion), China’s main strategic partner in the region. Overall, the Western Balkans account for less than 5% of China’s total trade with the 16+1/17+1 countries ($122 billion.)

China no doubt sees the region primarily as a market for its own exports and as an opening into Western European markets. While exports from the Western Balkans to China have increased over the years, the actual trade balance favors China — by almost 90%. The region’s exports to China amount to $634 million, while imports of Chinese products into the Western Balkans have reached $5.7 billion.

Given the need for investment and low production costs in the region, we might see a future trade-substituting investment strategy that could potentially allow Chinese companies to circumvent trade restrictions and export products directly to the EU market of 800 million people, thanks to the free trade agreements that Western Balkan countries enjoy with the EU.

Chinese investment: real FDI?

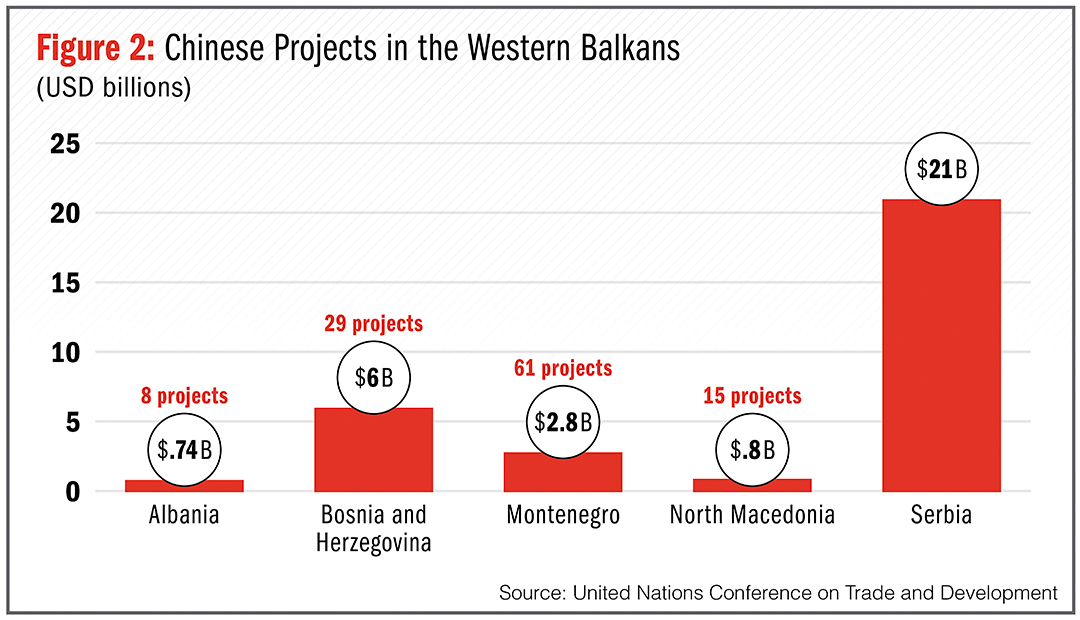

Over the past decade, Chinese investment in the region has grown rapidly. According to a new study from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, published in December 2021, there are 122 Chinese projects with an estimated value of $31 billion (27.6 billion euros). This makes up almost 40% of total foreign direct investment (FDI) in the five Western Balkan countries (excluding Kosovo), which amounted to $80 billion in 2020, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (See Figure 2)

A misleading aspect of the data on Chinese investment in the Western Balkans is that most of the money is not actual FDI, but loans. In fact, the main form of Chinese economic cooperation in the region is concessional lending for infrastructure, mainly for transportation and energy, through its state-owned banks and financial vehicles, including the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Sectors of economic cooperation are infrastructure, energy, mining and mineral processing, and communication technology, while engagement is mainly on a government-to-government basis. There have also been investments in the health sector, education and cultural centers. Despite all the activity, few projects have been concluded, most have been delayed, some have stalled, and for others, given the lack of transparency, the status is unclear. Allegations of corruption, environmental pollution and worker exploitation appear to be part of the overall fabric of these investments.

Chinese interest in Serbia is noteworthy. With the largest economy in the Western Balkans, Serbia has become Beijing’s go-to partner in the region and a clear bellwether within the 16+1 framework. Beijing’s long-term strategy in the Balkans views Serbia as a strategic European transportation hub. With 61 projects worth more than $21 billion, the most significant is the upgrade of the Belgrade-Budapest railway. Relations between Belgrade and Beijing extend beyond economics, as Serbia has also signed a $3 billion package for economic support and military purchases that has boosted Chinese influence in the country. Another important project is the Huawei-led installation of smart surveillance cameras with advanced facial and license plate recognition software, which is billed as a measure to fight crime but has raised concerns about its compatibility with EU privacy and data protection standards, as enshrined in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. However, the U.S. led a successful initiative in the area of security and technology to include the Western Balkans countries (except Serbia) in “The Clean Network,” a comprehensive approach to safeguarding the most sensitive information and assets of the governments, citizens and private companies from aggressive intrusions by malign actors, such as the Chinese Communist Party. It was specifically meant to counter Huawei’s efforts to gain a foothold in 5G networks, including in the Western Balkans.

The special bond between China and Serbia was further strengthened during the COVID-19 crisis, whereby China’s provision of its Sinopharm vaccine gave the Serbian government an important boost in managing the pandemic. However, China’s interest in accumulating a large portfolio of investments in Serbia is marred by strong concerns about environmental damage and data security issues.

Infrastructure: an important piece of the OBOR puzzle

China is mainly attracted to the Western Balkans for its geostrategic location and proximity to EU markets. In line with its OBOR objectives, Beijing is heavily investing in large-scale infrastructure projects and taking advantage of the urgent need for infrastructure in the region.

Beijing is developing China-EU trade corridors on land and on sea. These are important components of OBOR that link China with Western Europe via the Port of Piraeus in Greece and are supported by infrastructure networks in the Balkans. The Chinese state-owned China Ocean Shipping Co. (COSCO) owns a controlling 67% share of the Port of Piraeus, which has become the main entry point for Chinese goods in Europe, shortening normal shipping times by one week. Chinese goods travel by sea to Piraeus, then by train through North Macedonia and Serbia into Hungary and the Czech Republic. In 2019, COSCO bought a 60% majority stake of the Greek railway company Piraeus-Europe-Asia Rail Logistics and a minority stake in the Budapest train terminal in Hungary. Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) also hold a minority stake in the Port of Thessaloniki in Greece.

One of the biggest projects in the Western Balkans is the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway. This project was agreed to during the 16+1 summit in Riga, Latvia, in 2016. It is being financed at 85% by China’s Exim Bank ($2.5 billion) and built by the China Railway Construction Corp. For two sections of the Belgrade-Budapest railway, Serbia has already borrowed $1.5 billion. Another major Chinese transportation project in Serbia is the modernization of the 204-kilometer railway between Belgrade and Serbia’s third-largest city, Niš, which will eventually complete part of the Pan-European Corridor X that connects Salzburg, Austria, with the Port of Thessaloniki. The project is estimated to cost more than 2 billion euros, with the China Road and Bridge Corp. (CRBC) the likely tender recipient. The only completed, Chinese-funded infrastructure project in Serbia is the Pupin Bridge, China’s first big infrastructure investment project in Europe, which was carried out by CRBC and opened by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and his Serbian counterpart Aleksandar Vučić in December 2014.

North Macedonia is also an important country for OBOR. In 2013, the government of North Macedonia borrowed more than $800 million from China’s Exim Bank for the construction of two highways: the Miladinovci-Shtip highway, completed in August 2020, and the Kichevo-Ohrid highway (an integral part of European Corridor VIII), yet to be completed. Costs for construction, which is being done by China’s Sinohydro Corp., have increased to nearly $1.2 billion (with interest included). Both projects have been overshadowed by corruption allegations.

In Montenegro, the Bar-Boljare highway, from the Port of Bar on the Adriatic Sea to the border with Serbia, is the biggest Chinese project and signals the level of Chinese interest in the Port of Bar. It was financed by China’s Exim Bank for almost $1 billion for just the first section of the highway, making it one of the most expensive highways per kilometer in the world at $20 million per kilometer. It is being built by CRBC. Besides sending Montenegro’s sovereign debt rocketing to 103% of economic output — and with only 41 out of 165 kilometers completed — there are questions about the financial feasibility and unsustainable debt associated with “the road to nowhere.” According to Montenegrin government estimates, the remainder of the highway will cost an additional $2 billion. Chinese companies have also been involved in upgrading the railway network in Montenegro. In 2017, China Civil Engineering Construction Corp. completed reconstruction of a 10-kilometer segment of the Kolašin-Kos railway for $8 million. For Beijing, it was a very important project because it represented the first railway project in Europe built by a Chinese company using EU funds.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chinese construction companies are involved in building the 12-kilometer Počitelj-Zvirovići highway section costing $75 million and financed by the European Investment Bank.

China’s attempt to control regional infrastructure, however, was not as successful in Albania. In 2016, a state-backed Chinese company bought the concession to run Tirana International Airport, the only airport in the country at the time. Only four years after the deal and under less than clear circumstances, the concession was sold to a local company.

Infrastructure challenges

Investment in infrastructure is a public good that could foster sustainable economic development, but the positive developmental spillovers depend on the practical details of implementing these projects and the institutional absorptive capacities of the host countries. Considering the huge infrastructure deficits in the Western Balkans, Chinese state-backed enterprises can easily outcompete Western companies with their opaque ways of doing business. With Western Balkan political elites accepting high levels of corruption, the Chinese can take advantage of the lack of transparency in contract negotiations. Chinese SOEs engaging in infrastructure development have acquired experience in other developing countries. They also enjoy economies of scale and can offer cheaper prices as a direct result of the Chinese state’s interest in exporting its excess capacities and construction material, such as steel and cement.

Although much needed, these infrastructure projects and Chinese lending agreements are burdening the poor governments in the region with large debt obligations and unsustainable deals. The lack of due diligence results in sovereign guarantees shifting risk onto host countries at the expense of their financial stability. The resulting outcome is debt servitude to China. Montenegro is the perfect case study in this regard. Secret, single-bid contracts are usually awarded directly to Chinese SOEs without international public tenders or transparency. These opaque deals hide the responsible parties and create opportunities for corruption while allowing Chinese labor infiltration and degradation of the environment.

Another vulnerability is the ease with which Chinese-backed projects can be aligned with political cycles. When coupled with top-down rather than market-driven procurement decisions, Chinese business arrangements allow Balkan decision-makers to fuel patronage networks and boost short-term electoral advantages by focusing on short-term, unsustainable projects. Chinese fast money seems an easy way to maintain power to many Western Balkan leaders, and the political alignment of most media has not allowed broader public discussion of China’s activities in the region.

Energy and mining

By investing in countries rich in natural resources, such as steel, copper and oil, China aims to secure a supply of commodities. The Balkan energy sector is also very attractive for Chinese SOEs because major Western utility companies are unwilling to make large capital investments. Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro are attractive for their hydropower generation capacity, while Croatia, North Macedonia and Serbia offer wind energy potential. Chinese investments in these areas are mainly focused on acquisitions and privatization.

In 2016, China’s state-owned Hesteel Group took over the steel mill in Smederevo, Serbia, for $55 million. Smederevo was a former U.S. investment that U.S. Steel sold back to the Serbian government in 2012 for a symbolic price of $1. Hesteel’s Serbian subsidiary, HBIS Group Serbia, has become the country’s biggest export company. The RTB Bor copper factory represents another important Chinese investment in Serbia’s mining industry. Zijin Mining Group holds the controlling majority interest, an estimated investment of more than $1 billion, and has plans for expansion.

China Machinery Engineering Corp. is building a third, 350-megawatt unit at the Kostolac thermal coal power plant east of Belgrade, funded by a $600 million Exim Bank loan, as well as the expansion of the Drmno open cast lignite mine in the Kostolac basin. Serbia meets 70% of its electricity needs with lignite, and concerns have been raised that Chinese investment in coal plants and mines are delaying coal phaseout plans and hindering Serbia’s progress away from fossil fuels. Although significant investments support the Serbian economy and are good for local employment, concerns related to environmental pollution have sparked protests.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chinese interest has focused on two big energy projects, the Stanari lignite coal power plant project in 2013, financed at $400 million by China Development Bank, and the Tuzla lignite power plant in 2017. The latter is financed by an $800 million loan from Exim Bank and implemented by the China Gezhouba Group, part of China Energy Engineering Corp. These two projects have accumulated more than $1.2 billion of debt, which equals 13% of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s external debt and is becoming an iconic example of the clash between Chinese investments and EU standards in the Balkans. In 2020, the government of the Republika Srpska, one of the two political entities that make up Bosnia-Herzegovina, signed an agreement with China Gezhouba Group for a $216 million investment to build the Dabar hydropower plant in the country’s south. Another investment from China Electric and Polish-Chinese firm Sunningwell International has been announced for the construction of the Ugljevik 3 thermal power plant.

Since it purchased Canadian energy company Bankers Petroleum in 2016, China’s Geo-Jade Petroleum has controlled the concession (about $450 million) to the largest oil field in Albania. The Patos Marinz field near the city of Fier produces 95% of Albania’s crude oil and accounts for 11% of its exports. This is also one of the largest onshore oil fields in Southeast Europe. According to Bankers Petroleum, it is the largest foreign investor, largest taxpayer and one of the largest employers in Albania, but it recently experienced environmental problems and was fined by state authorities.

China also has a major investment in Albanian copper mining. In 2014, Jiangxi Copper Corp., the largest copper producer, manufacturer and distributor of copper products in China, bought a $65 million, 50% stake in Ekin Maden Tic. San. A.S., a Turkish-owned mining company operating in Albania. The Turkish-Chinese joint venture has a concession until 2043 for several copper mines and plants, and is the leading company for the exploration and processing of copper in Albania.

EU integration and environmental challenges

Coal-related projects in the region are not supported by European development banks or the World Bank due to environmental concerns and preferences for green energy. China, a large exporter of coal, is funding coal power plant investments in the Western Balkans, contrary to EU goals for the region. This is despite that the region remains one of the most polluted in Europe and is still largely dependent on lower-grade lignite coal for electricity production. Western Balkans countries are not technically bound by EU environmental standards, but power plants will need to be retrofitted to continue operations if EU membership is secured. While, these countries have committed to adopting the EU’s energy, transport and related standards, implementation is very poor due to weak institutions and vested economic interests. Hence, Chinese economic engagement in the region allows the Western Balkans countries to avoid costly EU environmental standards in the short run, while undermining their paths to EU integration.

Chinese soft power

Beijing’s narrative in the Western Balkans is centered on its promotion of the Chinese development model using its capital as an “economic miracle-maker,” and the mantra of “win-win” relations. The overwhelming majority of China-Western Balkans cooperation involves state institutions and is based on a system of shared interests built on past relationships and new personalities from civil society, academia and media.

Academic links between China and Western Balkan countries are growing. Aiming to build a community of friendly countries, Beijing is heavily investing in cultural diplomacy, from Confucius Institutes — present in every capital of the region with two in the Serbian capital of Belgrade — to chambers of commerce and cultural centers. In addition, Beijing promotes the creation of “Confucius classrooms” in primary and secondary schools. China has also made scholarships one of its public policy tools, offering them on bilateral bases, with Serbia receiving the highest number. Informal interactions between China and Western Balkans countries have grown through tourism, facilitated by visa relaxations and abolitions (Serbia and Albania). Governmental and party cooperation with China occurs at the bilateral and multilateral levels (China-Central and Eastern European Countries Young Political Leaders’ Forum), as seen in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

In recent years, there has been a marked rise in China’s media presence across the Western Balkans. China Radio International is an important media tool broadcasting in every language of the Balkans. News stories consist of information that is currently factual, neutral in tone, and oriented toward economic issues, but that generally lack critical evaluations of China’s activities. These outlets often seem to avoid references to information about questionable conditions attached to Chinese projects.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Western Balkans became a stage for China’s mask diplomacy. This strategy involved showering target countries with medical supplies and allowed China to depict itself as a generous donor while simultaneously trying to clear itself of accusations that it mishandled data during the first phase of the outbreak. Mask diplomacy was successful in some countries of the region, presenting China as a legitimate partner or even a savior, as depicted in images of Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić kissing the Chinese flag. When mask diplomacy turned into vaccine diplomacy, Serbia remained at the center of China’s strategy and took a strategic role, sharing Chinese vaccines with neighboring countries and creating “vaccine tourism.” The only country that did not use or accept Chinese vaccines was Kosovo. Vaccine diplomacy was clearly used by Beijing — and Moscow — to strengthen their geopolitical positions in the region to the detriment of Western powers, and to undermine the EU’s credibility.

Conclusions

The Western Balkans are struggling economically and in urgent need of investment. Beijing recognizes that it can easily establish a foothold on the edge of the EU, where its real interests lie. Political elites see the presence of China as purely economic and mostly opportunistic. Their focus appears completely void of any strategic analysis about the long-term implications of Chinese influence in the region.

Beijing’s diplomatic narrative supports the EU integration of the region, but several Chinese projects do not conform to EU standards and regulations of transparency and good governance. Issues of financial and environmental sustainability, debt dependency, lack of competition and state-led business models pose additional risk to the region, complicating the implementation of political reforms required for EU integration. Large-scale investments and the opening of new transportation routes could also serve as a vector of political and normative influence, and as an alternative to the Western democratic model of a liberal market economy.

Not having to comply with transparent tendering procedures, accountability and other elements of governance reform, but still receiving much-needed capital from China, could make Western Balkans’ leaders less dependent on the EU and enable them to preserve their vested economic interests.

Contrary to China’s “checkbook diplomacy,” the EU’s combined funds for infrastructure and economic development are larger and cheaper for recipient countries in the Western Balkans. Unfortunately, EU offers of aid may be less appealing than those from the Chinese because of cumbersome bureaucratic rules attached to EU funding and “enlargement fatigue,” but also due to weak strategic messaging to citizens in the region. The EU should not only reaffirm its open-door policy and move quicker to inject more certainty and predictability in the enlargement process, it should also keep governments in the region more transparent and accountable. Further delays run the risk of decreasing the region’s natural attraction toward the EU and creating space for competing visions to future EU integration.

From this perspective, the EU needs to incorporate China-specific measures when considering enlargement policy in the Western Balkans. It should demand increased transparency of Chinese projects, allow greater public scrutiny of their promised benefits and encourage the application of the EU FDI Screening Mechanism for strategic investment. This is essential to help build the region’s resilience — a key EU objective. More structured and stringent policies in the EU accession process — relating to environmental and procurement standards, economic governance and debt sustainability — will build capacities in the region’s governments and allow Western institutions to better define counterstrategies and increase transparency regarding Chinese government-to-government contracts, debt overreach and other hidden conditionalities.

The Western Balkans need to be part of a coordinated trans-Atlantic strategy toward China. The West in general needs better options for the Western Balkans and a clear strategy to develop economic opportunities and strengthen resilience, one aimed at promoting better foundations of democracy, rule of law and good governance.

The views expressed are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Marshall Center, the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Comments are closed.